SOUTH ASIA Post-Crisis Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiral Sunil Lanba, Pvsm Avsm (Retd)

ADMIRAL SUNIL LANBA, PVSM AVSM (RETD) Admiral Sunil Lanba PVSM, AVSM (Retd) Former Chief of the Naval Staff, Indian Navy Chairman, NMF An alumnus of the National Defence Academy, Khadakwasla, the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington, the College of Defence Management, Secunderabad, and, the Royal College of Defence Studies, London, Admiral Sunil Lanba assumed command of the Indian Navy, as the 23rd Chief of the Naval Staff, on 31 May 16. He was appointed Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee on 31 December 2016. Admiral Lanba is a specialist in Navigation and Aircraft Direction and has served as the navigation and operations officer aboard several ships in both the Eastern and Western Fleets of the Indian Navy. He has nearly four decades of naval experience, which includes tenures at sea and ashore, the latter in various headquarters, operational and training establishments, as also tri-Service institutions. His sea tenures include the command of INS Kakinada, a specialised Mine Countermeasures Vessel, INS Himgiri, an indigenous Leander Class Frigate, INS Ranvijay, a Kashin Class Destroyer, and, INS Mumbai, an indigenous Delhi Class Destroyer. He has also been the Executive Officer of the aircraft carrier, INS Viraat and the Fleet Operations Officer of the Western Fleet. With multiple tenures on the training staff of India’s premier training establishments, Admiral Lanba has been deeply engaged with professional training, the shaping of India’s future leadership, and, the skilling of the officers of the Indian Armed Forces. On elevation to Flag rank, Admiral Lanba tenanted several significant assignments in the Navy. As the Chief of Staff of the Southern Naval Command, he was responsible for the transformation of the training methodology for the future Indian Navy. -

India-Pakistan Conflict: Records of the Us State Department, February 1963

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICT: RECORDS OF THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT, FEBRUARY 1963-1966 Over 16,000 pages of State Department Central Files on India and Pakistan from 1963 through 1966 make this collection a standard documentary resource for the study of the political relations between India and Pakistan during a crucial period in the Cold War and the shifting alliances and alignments in South Asia. Date Range: 1963-1966 Content: 15,387 images Source Library: U.S. National Archives Detailed Description: Relations with Pakistan have demanded a high proportion of India’s international energies and undoubtedly will continue to do so. India and Pakistan have divergent national ideologies and have been unable to establish a mutually acceptable power equation in South Asia. The national ideologies of pluralism, democracy, and secularism for India and of Islam for Pakistan grew out of the pre-independence struggle between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, and in the early 1990s the line between domestic and foreign politics in India’s relations with Pakistan remained blurred. Because great-power competition—between the United States and the Soviet Union and between the Soviet Union and China—became intertwined with the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India was unable to attain its goal of insulating South Asia from global rivalries. This superpower involvement enabled Pakistan to use external force in the face of India’s superior endowments of population and resources. The most difficult problem in relations between India and Pakistan since partition in August 1947 has been their dispute over Kashmir. -

Report on Evaluation of Empowerment of Women in District Mansehra Through Women Friendly Halls

Report on Evaluation of Empowerment of Women in District Mansehra through Women Friendly Halls Sidra Fatima Minhas 11/27/2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 4 1. Women Freindly Halls (WFH) ......................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 8 1.1.1 Geographical Background ................................................................................ 9 1.1.2 Socio Cultural Context .....................................................................................12 1.1.3 Women Friendly Halls Project .........................................................................12 1.1.4 Objectives of WFHs Project ............................................................................13 1.2 Presence and Activities of Other Players ................................................................14 1.3 Rationale of the Evaluation .....................................................................................15 1.3.1 Objectives and Aim of the Evaluation ..............................................................15 1.4 Scope of the Evaluation .........................................................................................16 1.4.1 Period and Course of Evaluation .....................................................................16 1.4.2 Geographical -

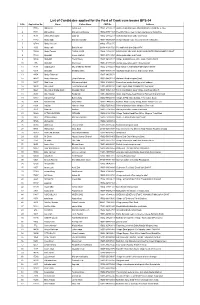

List of Candidates Applied for the Post of Cook-Cum-Bearer BPS-04 S.No Application No

List of Candidates applied for the Post of Cook-cum-bearer BPS-04 S.No Application No. Name Father Name CNIC No. Address 1 17715 Abbas Ali Akbar Gul 17301-2133451-1 Shaheen Muslim town, Mohallah Nazer Abad No 2, Hou 2 17171 Abbas khan Muhammad Sarwar 15602-0357410-5 The City School near to wali swat palace Saidu,Sha 3 7635 abbas khan zafar zafar ali 15602-2565421-7 mohalla haji abad saidu sharif swat 4 11483 Abdul aziz Muhammad jalal 15601-4595672-7 village baidara moh: school area teh:matta dist : 5 12789 Abdul Haleem - 90402-3773217-5 - 6 3090 Abdul Jalil Bakht Munir 21104-4193372-9 P/o and tehsil khar Bajur KPK 7 15909 Abdul Tawab FAZAL AHAD 15602-1353439-1 NAWAKALY MUHALA QANI ABADAN TEHSIL BABOZAY SWAT 8 17442 Abdullah Aleem bakhsh 15607-0374932-1 Afsar abad saidu sharif swat 9 10806 Abdullah Fazal Raziq 15607-0409351-5 Village Gulbandai p.o office saidu sharif tehsil b 10 255 Abdullah Mehmood 15602-6117033-5 Jawad super store panr mingora swat 11 7698 ABDULLAH MUHAMMAD IKRAM 15602-2135660-7 MOH BACHA AMANKOT MINGORA SWAT 12 4215 Abdullah Sarfaraz khan 15607-0359153-1 Almadina Model School and College Swat 13 4454 Abdur Rahman - 15607-0430767-1 - 14 14147 Abdur Rahman Umar Rahman 15602-0449712-7 Rahman Abad mingora Swat 15 12477 Abid khan Muhammad iqbal 15602-2165882-7 khunacham saidu sharif po tehsil babuxai 16 14428 Abu Bakar Tela Muhammad 17301-6936018-1 Ghari Inayat Abad Gulbahar # 2 Peshawar 17 10621 Abu Bakar Sadiq Shah Muqadar Shah 15607-0352136-7 Tehsil and District Swat Village and Post office R 18 9436 Abu Bakkar Barkat Ali 15607-0443898-5 Ikram Cap House Near Kashmir Backers Nishat Chowk 19 13113 Adnan Khan Bakht Zada 15602-9084073-3 Village & P/O: Bara Bandai, Teh: Kabal ,Swat. -

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - Daily Flood Report Date (29 09 2011)

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - Daily Flood Report Date (29 09 2011) SWAT RIVER Boundary 14000 Out Flow (Cusecs) 12000 International 10000 8000 1 3 5 Provincial/FATA 6000 2 1 0 8 7 0 4000 7 2 4 0 0 2 0 3 6 2000 5 District/Agency 4 4 Chitral 0 Gilgit-Baltistan )" Gauge Location r ive Swat River l R itra Ch Kabul River Indus River KABUL RIVER 12000 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Kurram River 10000 Out Flow (Cusecs) Kohistan 8000 Swat 0 Dir Upper Nelam River 0 0 Afghanistan 6000 r 2 0 e 0 v 0 i 1 9 4000 4 6 0 R # 9 9 5 2 2 3 6 a Dam r 3 1 3 7 0 7 3 2000 o 0 0 4 3 7 3 1 1 1 k j n ") $1 0 a Headworks P r e iv Shangla Dir L")ower R t a ¥ Barrage w Battagram S " Man")sehra Lake ") r $1 Amandara e v Palai i R Malakand # r r i e a n Buner iv h J a R n ") i p n Munda n l a u Disputed Areas a r d i S K i K ") K INDUS RIVER $1 h Mardan ia ") ") 100000 li ") Warsak Adezai ") Tarbela Out Flow (Cusecs) ") 80000 ") C")harsada # ") # Map Doc Name: 0 Naguman ") ") Swabi Abbottabad 60000 0 0 Budni ") Haripur iMMAP_PAK_KP Daily Flood Report_v01_29092011 0 0 ") 2 #Ghazi 1 40000 3 Peshawar Kabal River 9 ") r 5 wa 0 0 7 4 7 Kh 6 7 1 6 a 20000 ar Nowshera ") Khanpur r Creation Date: 29-09-2011 6 4 5 4 5 B e Riv AJK ro Projection/Datum: GCS_WGS_1984/ D_WGS_1984 0 Ghazi 2 ") #Ha # Web Resources: http://www.immap.org Isamabad Nominal Scale at A4 paper size: 1:3,500,000 #") FATA r 0 25 50 100 Kilometers Tanda e iv Kohat Kohat Toi R s Hangu u d ") In K ai Map data source(s): tu Riv ") er Punjab Hydrology Irrigation Division Peshawar Gov: KP Kurram Garhi Karak Flood Cell , UNOCHA RIVER $1") Baran " Disclaimers: KURRAM RIVER G a m ") The designations employed and the presentation of b e ¥ Kalabagh 600 Bannu la material on this map do not imply the expression of any R K Out Flow (Cusecs) iv u e r opinion whatsoever on the part of the NDMA, PDMA or r ra m iMMAP concerning the legal status of any country, R ") iv ") e K territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 400 r h ") ia the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

A Look Into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan Over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori

A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/07/a-look-into-the-conflict-between-india-and-pakistan-over-kashmir/ PRANAV ASOORI, OCT 7 2020 The region of Kashmir is one of the most volatile areas in the world. The nations of India and Pakistan have fiercely contested each other over Kashmir, fighting three major wars and two minor wars. It has gained immense international attention given the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers and this conflict represents a threat to global security. Historical Context To understand this conflict, it is essential to look back into the history of the area. In August of 1947, India and Pakistan were on the cusp of independence from the British. The British, led by the then Governor-General Louis Mountbatten, divided the British India empire into the states of India and Pakistan. The British India Empire was made up of multiple princely states (states that were allegiant to the British but headed by a monarch) along with states directly headed by the British. At the time of the partition, princely states had the right to choose whether they were to cede to India or Pakistan. To quote Mountbatten, “Typically, geographical circumstance and collective interests, et cetera will be the components to be considered[1]. -

Field-Based Analytical Methods for Explosive Compounds

Field-Based Analytical Methods for Explosive Compounds Dr. Thomas F. Jenkins Marianne E. Walsh USA Engineer Research and Development Center– Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory 72 Lyme Road, Hanover NH 03755 603-646-4385 (FAX-4785) [email protected] [email protected] 1 1 Outline of Presentation • Important properties of nitroaromatic (TNT) and nitramine (RDX) explosives • Accepted laboratory methods for explosives chemicals • Detection criteria for explosives-related chemicals • Why should you consider using on-site methods? • Sampling considerations for explosives in soil and water • Verified methods for on-site determination of explosives in soil and water • Advantages / disadvantages of various on-site methods 2 Overview of topics to be covered in the presentation. 2 ***Safety*** • Chunks of high explosives often found at contaminated sites • Concentrations of TNT or RDX in soil greater than 12% are reactive (can propagate a detonation)* • Neither chunks nor soil with concentrations of TNT and RDX greater than 10% can be shipped off site using normal shipping procedures *Kristoff et al. 1987 3 The most important property of all is the ability of these compounds to detonate if they are subjected to the right type of stimulus (spark, shock). This is one of the major reasons why on-site analysis is so important for explosives. Kristoff, F.T., T.W. Ewing and D.E. Johnson (1987) Testing to Determine Relationship Between Explosive Contaminated Sludge Components and Reactivity. USATHAMA Report No. AMXTH-TE-CR-86096, -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

The Russian Job

The Russian Job The rise to power of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation “We did not reject our past. We said honestly: The history of the Lubyanka in the twentieth century is our history…” ~ Nikolai Platonovich Patrushev, Director of the FSB Between August-September 1999, a series of explosions in Russia killed 293 people: - 1 person dead from a shopping centre explosion in Moscow (31 st August) - 62 people dead from an apartment bombing in Buynaksk (4 th September) - 94 people dead from an apartment bombing in Moscow (9th September) - 119 people dead from an apartment bombing in Moscow (13 th September) - 17 people dead from an apartment bombing in Volgodonsk (16 th September) The FSB (Federal Security Service) which, since the fall of Communism, replaced the defunct KGB (Committee for State Security) laid the blame on Chechen warlords for the blasts; namely on Ibn al-Khattab, Shamil Basayev and Achemez Gochiyaev. None of them has thus far claimed responsibility, nor has any evidence implicating them of any involvement been presented. Russian citizens even cast doubt on the accusations levelled at Chechnya, for various reasons: Not in living memory had Chechen militias pulled off such an elaborated string of bombings, causing so much carnage. A terrorist plot on such a scale would have necessitated several months of thorough planning and preparation to put through. Hence the reason why people suspected it had been carried out by professionals. More unusual was the motive, or lack of, for Chechens to attack Russia. Chechnya’s territorial dispute with Russia predates the Soviet Union to 1858. -

India's Military Strategy Its Crafting and Implementation

BROCHURE ONLINE COURSE INDIA'S MILITARY STRATEGY ITS CRAFTING AND IMPLEMENTATION BROCHURE THE COUNCIL FOR STRATEGIC AND DEFENSE RESEARCH (CSDR) IS OFFERING A THREE WEEK COURSE ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. AIMED AT STUDENTS, ANALYSTS AND RESEARCHERS, THIS UNIQUE COURSE IS DESIGNED AND DELIVERED BY HIGHLY-REGARDED FORMER MEMBERS OF THE INDIAN ARMED FORCES, FORMER BUREAUCRATS, AND EMINENT ACADEMICS. THE AIM OF THIS COURSE IS TO HELP PARTICIPANTS CRITICALLY UNDERSTAND INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY INFORMED BY HISTORY, EXAMPLES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE. LED BY PEOPLE WHO HAVE ‘BEEN THERE AND DONE THAT’, THE COURSE DECONSTRUCTS AND CLARIFIES THE MECHANISMS WHICH GIVE EFFECT TO THE COUNTRY’S MILITARY STRATEGY. BY DEMYSTIFYING INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY AND WHAT FACTORS INFLUENCE IT, THE COURSE CONNECTS THE CRAFTING OF THIS STRATEGY TO THE LOGIC BEHIND ITS CRAFTING. WHY THIS COURSE? Learn about - GENERAL AND SPECIFIC IDEAS THAT HAVE SHAPED INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY ACROSS DECADES. - INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS AND PROCESSES. - KEY DRIVERS AND COMPULSIONS BEHIND INDIA’S STRATEGIC THINKING. Identify - KEY ACTORS AND INSTITUTIONS INVOLVED IN DESIGNING MILITARY STRATEGY - THEIR ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES. - CAUSAL RELATIONSHIPS AMONG A MULTITUDE OF VARIABLES THAT IMPACT INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. Understand - THE REASONING APPLIED DURING MILITARY DECISION MAKING IN INDIA - WHERE THEORY MEETS PRACTICE. - FUNDAMENTALS OF MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND ESCALATION/DE- ESCALATION DYNAMICS. - ROLE OF DOMESTIC POLITICS IN AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. - THREAT PERCEPTION WITHIN THE DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT AND ITS MILITARY ARMS. Explain - INDIA’S MILITARY ORGANIZATION AND ITS CONSTITUENT PARTS. - INDIA’S MILITARY OPTIONS AND CONTINGENCIES FOR THE REGION AND BEYOND. - INDIA’S STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS AND OUTREACH. -

Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q

Not a ‘Wal-Mart’, but an ‘Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q. Khan Network Strategic Insights , Volume VI, Issue 5 (August 2007) by Bruno Tertrais Strategic Insights is a bi-monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. The views expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of NPS, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Introduction Much has been written about the A.Q. Khan network since the Libyan “coming out” of December 2003. However, most analysts have focused on the exports made by Pakistan without attempting to relate them to Pakistani imports. To understand the very nature of the network, it is necessary to go back to its “roots,” that is, the beginnings of the Pakistani nuclear program in the early 1970s, and then to the transformation of the network during the early 1980s. Only then does it appear clearly that the comparison to a “Wal-Mart” (the famous expression used by IAEA Director General Mohammed El-Baradei) is not an appropriate description. The Khan network was in fact a privatized subsidiary of a larger, State-based network originally dedicated to the Pakistani nuclear program. It would be much better characterized as an “imports-exports enterprise.” I. Creating the Network: Pakistani Nuclear Imports Pakistan originally developed its nuclear complex out in the open, through major State-approved contracts. Reprocessing technology was sought even before the launching of the military program: in 1971, an experimental facility was sold by British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL) in 1971. -

(Defence Wing) Govenjnt of India New Vice Chief Of

PRESS INFOREATION BUREAU (DEFENCE WING) GOVENJNT OF INDIA NEW VICE CHIEF OF NAVY FLAG OFFICER COJ'INANDING—IN_CHIEF, sOVTHERN NAVAL CONMAND AND DEPUTY CHIEF OF NAVY ANNOUNCED New Delhi Agrahayana 07, 19109 November 28, 1987 Vice Admiral GN Hiranandani presently Flag Officer Commanding—in—Chief, Southern Naval Command (FOC—in—C, SNC) has been appointed as Vice Chief of Naval Staff. He will take over from Vice Admiral JG Nadkarni, the CNS Designate, who will assume the ofice of Chief of the Naval Staff on November Oth in the rank of Admiral. Vice Admiral L. Ramdas presently Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff has been appointed FOC—in—C, SNC. Vice Admiral RP Sawhney, presently Controller Warship Production and Acquisition at Naval Headnuarters, has been appointed as Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff. Vice Admiral GM Hiranandani -was commissioned in 1952 and received his initial training in the United Kingdom and later graduated from the Staff College, Greenwich (U.K.). In 1 971 he served as the Fleet Operations Officer, Western Fleet. His notable - commands at sea include that of the first Kashin class destroyer, INS Rajput which he commissioned in 1980. On promotion to flag rank he was appointed Chief of Staff, Western Naval Command and later Deputy Chief of Naval Staff in the rank of Vice Admiral. He is a recipient of the Param Vishst Seva Medal, Ati Vishist Seva, Medal and Nao Sena Medal. .1,2 -2-- Vice Admiral L. Ramdas was commissioned in 1953 and received his initial trai lug in the U.K.. A communication Specialist, he has held a number of importanf commands a't sea, which inolde Command of the Eastern Fleet, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant and a modern patrol vessel squadron.