Copyright by Chelsea Lea Weathers 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Quinn Captured

Opening ReceptiOn: june 28, 7pm–10pm AdmissiOn is fRee Joan Quinn Captured Curated by Laura Whitcomb and organized by Brand Library Art Galleries panel discussions, talks and film screenings have been scheduled in conjunction with this gallery exhibition. Programs are free and are by reservation only. Tickets may be Joan Quinn Captured reserved at www.glendalearts.org. Join us for the opening reception on Saturday, June 28th, 7:00pm – 10:00pm. 6/28 EmErging LandscapE: 7/17 WarhoL/basquiat/quinn Los angeles 5:00pm film Jean Michel Basquiat: The exhibition ‘Joan Quinn Captured’ will 2:00pm panel Modern Art in Los Angeles: The Radiant Child showcase what is perhaps the largest portrait ‘Cool School’ Oral History Ed Moses 6:30pm panel Warhol & Basquiat: collection by contemporary artists in the world, 3:00PM film LA Suggested by the Art The Magazine of the 80s, Joan including such luminaries as Jean-Michel of Ed Ruscha Quinn’s work for Interview, the Basquiat, Shepard Fairey, Frank Gehry, Manipulator & Stuff Magazine; Robert Graham, David Hockney, Ed Ruscha, 4:30PM panel Los Angeles and the Contemporary Art Dawn Special Speaker Matthew Rolston Beatrice Wood and photographers Robert 7:00pm film Andy Warhol: Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, Matthew Rolston and Arthur A Documentary Film Tress. For the first time, this portrait collection will be exhibited in 7/3 EtErnaL rEturn collaboration with renowned works of the artists encouraging a 5:00pm film Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada dialogue between the portraits and specific artist movements. The 7/24 don bachardy exhibition will also portray the world Joan Agajanian Quinn captured 6:30pm film Duggie Fields’ Jangled 6:00pm film Chris & Don: A Love Story as editor for her close friend Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, 7:00pm talk Guest Artist Duggie Fields 7:30pm film Memories of Berlin: along with contributions to some of the most important fanzines of 8:00pm film The Great Wen the 1980’s that are proof of her role as a critical taste maker of her The Twilight of Weimar Culture time. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

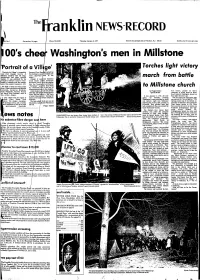

T"° Anklin News-Record

T"° anklin news-recorD one section, 24 pages / Phone 725-3300 Thursday, January 6, 1977 Second class postage paid at Princeton, N.J. 08540 I!,No. 1 $4.50 a year/t5 cents per copy O0’s chee Washington’s men in Millstone a ViI ge’ Torches light victory 0Portrait"Portrait of a Village"is a carefullyof Somerset Court HouLppreaehed the segched 50-page hislory of Revolutionary Millstone, complete with 100 .maps, most important photographs and other graphic county’." march from battle iisplays. It was published by the Chapter II deal Somerset mrough’s Historic District Com- Court House ant American nissinn to coincide with the reenact- Revolution,and it’ ~ on this chapter nent of the events of January3, 1777. that the ial production The book is edited by Diane Jones "Turnabout" was Hap Heins to Millstone church ;tiney. Othercontributors are Marllyn Sr. contributed a in the way of information and s to this chapter. :antarella, Katharine Erickson, Otherchapters ¢LI with the periods by Peggy Roeske Van Doren, played by Terry 3rnce Marganoff, Patricia Nivlson Special Writer Jamieson, at whose house on River md Barrie Alan Peterson, each of who.n wrote a chapter. times. The final c is "250 Years Road General Washington stayed on of Local ChurchI tracing the It was January 3, 1T/7, all over that night 200 years ago. ’ ~pter I deals with the origins of history of the DuReform Church in again. On Monday evening The play gave the imnression that ~erset Court House tnow Millstone. Washingten’s army marched by torch war was not all *’fun and games."The The chapter concludes: The booksells can be and lantern light into Millstone opening scene was of the British ca- forge, farms, and a variety obtained b following the victory that morningat cups(ion of Millstone (then Somerset all industriesas wellas its legal 359-1361. -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

The Critical Impact of Transgressive Theatrical Practices Christopher J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 (Im)possibilities of Theatre and Transgression: the critical impact of transgressive theatrical practices Christopher J. Krejci Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Krejci, Christopher J., "(Im)possibilities of Theatre and Transgression: the critical impact of transgressive theatrical practices" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3510. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3510 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. (IM)POSSIBILITIES OF THEATRE AND TRANSGRESSION: THE CRITICAL IMPACT OF TRANSGRESSIVE THEATRICAL PRACTICES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Theatre by Christopher J. Krejci B.A., St. Edward’s University, 1999 M.L.A, St. Edward’s University, 2004 August 2011 For my family (blood and otherwise), for fueling my imagination with stories and songs (especially on those nights I couldn’t sleep). ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, John Fletcher, for his expert guidance. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Ruth Bowman, Femi Euba, and Les Wade, for their insight and support. -

Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2014 Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation H. King, "Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable," Criticism 56.3 (Fall 2014): 457-479. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/72 For more information, please contact [email protected]. King 6/15/15 Page 1 of 30 Stroboscopic:+Andy+Warhol+and+the+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable+ by+Homay+King,+Associate+Professor,+Department+of+History+of+Art,+Bryn+Mawr+College+ Published+in+Criticism+56.3+(Fall+2014)+ <insert+fig+1+near+here>+ + Pops+and+Flashes+ At+least+half+a+dozen+distinct+sources+of+illumination+are+discernible+in+Warhol’s+The+ Velvet+Underground+in+Boston+(1967),+a+film+that+documents+a+relatively+late+incarnation+of+ Andy+Warhol’s+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable,+a+multimedia+extravaganza+and+landmark+of+ the+expanded+cinema+movement+featuring+live+music+by+the+Velvet+Underground+and+an+ elaborate+projected+light+show.+Shot+at+a+performance+at+the+Boston+Tea+Party+in+May+of+ 1967,+with+synch+sound,+the+33\minute+color+film+combines+long+shots+of+the+Velvet+ -

Healthy Eating for Seniors Handbook

Healthy Eating for Seniors Acknowledgements CThehapter Healthy Eating for Seniors1 handbook was originally developed by the British Columbia Ministry of Health in Eat2008. Well, Many seniors Ageand dietitians Well were involved in helping to determine the content for the handbook – providing Therecipes, news isstories good. and Canadian ideas and generallyseniors contributingage 65 to andmaking over are Healthy living Eating longer for thanSeniors ever a useful before. resource. The WellMinistry after they of Health retire, would they like are to continuing acknowledge to and thank all participatethe individuals in their involved communities in the original and development to enjoy of this satisfying,resource. energetic, well-rounded lives with friends and family. For the 2017 update of the handbook, we would like However,to thank recent the public surveys health investigating dietitians from thethe regional eatinghealth and authorities exercise for habits providing of Canadians feedback on – the age nutrition 65 tocontent 84 – revealof the handbook. that seniors The couldupdate bewas doing a collaborative evenproject better. between the BC Centre for Disease Control and the Ministry of Health and made possible through funding from the BC Centre for Disease Control (an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority). Healthy Eating for Seniors Handbook Update PROJECT TEAM • Annette Anderwald, registered dietitian (RD) • Cynthia Buckett, MBA, RD; provincial manager, Healthy Eating Resource Coordination, BC Centre for Disease Control -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

100 Cans by Andy Warhol

Art Masterpiece: 100 Cans by Andy Warhol Oil on canvas 72 x 52 inches (182.9 x 132.1 cm) Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery Keywords: Pop Art, Repetition, Complimentary Colors Activity: 100 Can Collective Class Mural Grade: 5th – 6th Meet the Artist • Born Andrew Warhol in 1928 near Pittsburgh, Pa. to Slovak immigrants. His father died in a construction accident when Andy was 13 years old. • He is known as an American painter, film-maker, publisher and major figure in the pop art movement. • Warhol was a sickly child, his mom would give him a Hershey bar for every coloring book page he finished. He excelled in art and won a scholarship to college. • After college, he moved to New York City and became a magazine illustrator – became known for his drawings of shoes. His mother lived with him – they had no hot water, the bathtub was in the kitchen and had up to 20 cats living with them. Warhol ate tomato soup every day for lunch. Chandler Unified School District Art Masterpiece • In the 1960’s, he started to make paintings of famous American products such as soup cans, coke bottles, dollar signs & celebrity portraits. He became known as the Prince of Pop – he brought art to the masses by making art out of daily life. • Warhol began to use a photographic silk-screen process to produce paintings and prints. The technique appealed to him because of the potential for repeating clean, hard-edged shapes with bright colors. • Andy wanted to remove the difference between fine art and the commercial arts used for magazine illustrations, comic books, record albums or ad campaigns. -

LAURITZ MELCHIOR: a APPRECIATIO R, H) Jonathan Chiller - 5

' CoRN ExcHANGE BANK TRusT Co. Established 1853 A Bank Statement that any Man or Woman can Understand Condensed Statement as of Close of Business September 30th, 1939 Due Individuals, Firms, Corporations and Banks . $329,420,341.29 To meet this indebtedness we have : Cash in Vaults and Due from Banks . $136,209,114.30 Cash Items in Process of Collection 15,465,034.91 U. S. Government Securities . 119,336,598.65 (Direct and fully guaranteed, including $3,051,000 pledged to secure deposits and for other pur· poses as required by law. Canadian Government Securities 4,978,312.34 State, County and Municipal Bonds 3,949,336.41 Other Tax Exempt Bonds 5,785,235.96 Railroad Bonds . 5,673,756.93 Public Utility Bonds 7,361,634.67 Industrial and Other Bonds . 2,925,146.46 18,000 Shares Federal Reserve Bank of N. Y. 900,000.00 2,499 Shares of Discount Corp. of N. Y. at cost 299,880.00 9,990 Shares of Corn Exchange Safe Deposit Co. 824,000.00 Sundry Securities 387,735.00 Secured Demand Loans . 14,817,093.34 Secured Time Loans 1,994,164.72 *Loans and Discounts Unsecured 9,935,871.40 *First Mortgages 17,945,685.86 Customers' Liability on Acceptances 864,671.91 *Banking Houses Owned 12,055,11 8.92 *Other Real Estate Owned . 1,955,575.45 Accrued Interest Receivable 1,124,412.62 Other Assets 148,676.12 Tot1l to Meet Indebtedness . $364,937,055.97 This leaves . $35,516,714.68 *Less Reserves. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker.