Researching J.R.R. Tolkien: How Kalevala Influenced His Legendarium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Story of Kullervo Pdf Ebook by J.R.R. Tolkien

Download The Story of Kullervo pdf ebook by J.R.R. Tolkien You're readind a review The Story of Kullervo ebook. To get able to download The Story of Kullervo you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: The Story of Kullervo 192 pages Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; First Edition edition (April 5, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780544706262 ISBN-13: 978-0544706262 ASIN: 0544706269 Product Dimensions:5.5 x 0.8 x 8.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 6717 kB Description: The first publication of a previously unknown work of fantasy by J.R.R. TolkienKullervo, son of Kalervo, is perhaps the darkest and most tragic of all J.R.R. Tolkien’s characters. Hapless Kullervo, as Tolkien called him, is a luckless orphan boy with supernatural powers and a tragic destiny.Brought up in the homestead of the dark magician Untamo,... Review: Disclaimer: I love Tolkien, as in: Ive read The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, and the Silmarillion more times than I can remember. I also read The Children of Hurin and enjoyed that story.If youre looking for a book that will shed light on how Tolkien developed his literary world, what his influences were, and if you want to find out more about how... Book Tags: story of kullervo pdf, children of hurin pdf, verlyn flieger pdf, lord of the rings pdf, notes and commentary pdf, actual story pdf, editor verlyn pdf, source material pdf, unfinished work pdf, land of heroes pdf, sold into slavery pdf, later works pdf, dark tale pdf, sister wanona pdf, twin sister pdf, buy this book pdf, epic poem pdf, think it is great pdf, pages long pdf, finnish epic The Story of Kullervo pdf ebook by J.R.R. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Small Renaissances Engendered in JRR Tolkien's Legendarium

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2017 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Dominic DiCarlo Meo Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meo, Dominic DiCarlo, "'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 555. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/555 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Abstract After surviving the trenches of World War I when many of his friends did not, Tolkien continued as the rest of the world did: moving, growing, and developing, putting the darkness of war behind. He had children, taught at the collegiate level, wrote, researched. Then another Great War knocked on the global door. His sons marched off, and Britain was again consumed. The "War to End All Wars" was repeating itself and nothing was for certain. In such extended dark times, J. R. R. Tolkien drew on what he knew-language, philology, myth, and human rights-peering back in history to the mythologies and legends of old while igniting small movements in modern thought. Arthurian, Beowulfian, African, and Egyptian myths all formed a bedrock for his Legendarium, and fantasy-fiction as we now know it was rejuvenated.Just like the artists, authors, and thinkers from the Late Medieval period, Tolkien summoned old thoughts to craft new creations that would cement themselves in history forever. -

Arch : Northwestern University Institutional Repository

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Matthew Kane Sterenberg EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2007 2 © Copyright by Matthew Kane Sterenberg 2007 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain Matthew Sterenberg This dissertation, “Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth- Century Britain,” argues that a widespread phenomenon best described as “mythic thinking” emerged in the early twentieth century as way for a variety of thinkers and key cultural groups to frame and articulate their anxieties about, and their responses to, modernity. As such, can be understood in part as a response to what W.H. Auden described as “the modern problem”: a vacuum of meaning caused by the absence of inherited presuppositions and metanarratives that imposed coherence on the flow of experience. At the same time, the dissertation contends that— paradoxically—mythic thinkers’ response to, and critique of, modernity was itself a modern project insofar as it took place within, and depended upon, fundamental institutions, features, and tenets of modernity. Mythic thinking was defined by the belief that myths—timeless rather than time-bound explanatory narratives dealing with ultimate questions—were indispensable frameworks for interpreting experience, and essential tools for coping with and criticizing modernity. Throughout the period 1900 to 1980, it took the form of works of literature, art, philosophy, and theology designed to show that ancient myths had revelatory power for modern life, and that modernity sometimes required creation of new mythic narratives. -

Wäinämöisen Sammon Palautuksen Veneretki Rotary Alustus 28.2.2019, Väinö Åberg

1 / 5 Wäinämöisen Sammon palautuksen veneretki Rotary alustus 28.2.2019, Väinö Åberg Louhi lupasi Ilmariselle Sammon takomisesta Pohjan Neidon, mutta pettikin lupauksensa ja piti sekä Sammon että Neidon. Runo 10. Ihmisyyden Sammon taonta - käsiohjelma: http://www.samponetti.com/Sampo-k_siohj.pdf avaa Kalevalan symbo- liikkaa ja Kalevala Kartan Päijänteen-Enoveden-Vuohijärven-Pyhäjärven ja Kymijoen alueilta Kalevalan tapahtumien järjestyksessä, jonka maist. Matti Malin löysi noin 40 vuoden Kalevalan paikannimien tutkimuksilla. 1. Kalevala, Lönnrot ja muinaisrunojen satumainen Wiisaus Lönnrotin kokoama vanha Kalevala ilmestyi 1835 ja uusi Kalevala 1849. Kalevalan mukaan SAMPO ANTAA KAIKEN HYVÄN maailmassa, aineellisen ja aineettoman, ja Lönnrotin mielestä siihen ei pysty mikään muu elämässä kuin Suuri Elämä eli Jumala. - Sampo on sanskritiksi Sambhu = Jumala (Hyvyys) ja Sammon kansi = Sambhu kanta, on jumalan puoliso (Rakkaus). Sanskritin kieli on kaikkien kielten äitikieli, jonka sanakirjan paksuus on n. 15 m, 600 volymiä, kertoi sanskr. prof Asko Parpola. ”Jokamies, taiatko takoa Sammon eli puhdistaa Pohjolasi, so. sielusi tunteilut ja luulotiedot? Osaatko hillitä mielesi ja puheesi, ja laulaa oman alitajuntasi rumahisten rutkusakin Rutjankoskeen?” Taonnan TEKELEET: Jousi, Hieho, Vene, Aura. Vain Hengen voimilla, Tuulettarilla, Sampo syntyy eikä lihaksilla lietsomalla. Lietsojaorjat kahlehdittiin kallioon, jotta väkivalta ei sotkisi taontaa eli sydämen puhdistusta. 2. Kalevala-Kartta, Sammon takaisinhaun retkestä, jonka Wäinämöinen, Ilmarinen -

”Yksin Syntyi Väinämöinen”

0 ”Yksin syntyi Väinämöinen” Tarkastelussa Kalevalan Maailmansyntyruno Maaret Peltonen Kirjallisuuden kandidaatintutkielma Taiteiden ja kulttuurintutkimuksen laitos Jyväskylän yliopisto Ohjaaja: Anna Helle Opponentti: Hannamari Kilpeläinen Kevät 2016 1 SISÄLTÖ 1 Johdanto ................................................................................................. 2 2 Kalevalan synty ...................................................................................... 3 2.1 Runolaulajat ........................................................................................ 4 2.2 Runolaulajan maailma ......................................................................... 6 3 Myytit ja Kalevala .................................................................................. 6 4 Aineiston kuvaus ja analyysi ................................................................. 9 4.1 Aineiston kuvaus ................................................................................. 9 4.2 Aineiston analyysi ............................................................................... 11 5 Johtopäätökset ..................................................................................... 16 6 Päätäntö ................................................................................................ 17 Lähteet 2 1 Johdanto Tutkin kirjallisuuden kandidaatin tutkielmassani Kalevalan ja Raamatun välistä suhdetta ja yhteyttä. Etenen Kalevalan tutkimisessa myyttien kautta Raamattuun. Mielenkiintoni Kalevalan ja Raamatun väliseen yhteyteen on -

Visits to Tuonela Ne of the Many Mythologies Which Have Had an In

ne of the many mythologies which have had an in fluence on Tolkien's work was the Kalevala, the 22000- line poem recounting the adventures of a group of Fin nish heroes. It has many characteristics peculiar to itself and is quite different from, for example, Greek or Germanic mythology. It would take too long to dis cuss this difference, but the prominent role of women (particularly mothers) throughout the book may be no ted, as well as the fact that the heroes and the style are 'low-brow', as Tolkien described them, as opposed to the 'high-brow' heroes common in other mytholog- les visits to Tuonela (Hades) are fairly frequent; and magic and shape-change- ing play a large part in the epic. Another notable feature which the Kaleva la shares with QS is that it is a collection of separate, but interrelated, tales of heroes, with the central theme of war against Pohjola, the dreary North, running through the whole epic, and individual themes in the separate tales. However, it must be appreciated that QS, despite the many influences clearly traceable behind it, is, as Carpenter reminds us, essentially origin al; influences are subtle, and often similar incidents may occur in both books, but be employed in different circumstances, or be used in QS simply as a ba sis for a tale which Tolkien would elaborate on and change. Ibis is notice able even in the tale of Turin (based on the tale of Kullervo), in which the Finnish influence is strongest. I will give a brief synopsis of the Kullervo tale, to show that although Tolkien used the story, he varied it, added to it, changed its style (which cannot really be appreciated without reading the or iginal ), and moulded it to his own use. -

Clashing Perspectives of World Order in JRR Tolkien's Middle-Earth

ABSTRACT Fate, Providence, and Free Will: Clashing Perspectives of World Order in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth Helen Theresa Lasseter Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. Through the medium of a fictional world, Tolkien returns his modern audience to the ancient yet extremely relevant conflict between fate, providence, and the person’s freedom before them. Tolkien’s expression of a providential world order to Middle-earth incorporates the Northern Germanic cultures’ literary depiction of a fated world, while also reflecting the Anglo-Saxon poets’ insight that a single concept, wyrd, could signify both fate and providence. This dissertation asserts that Tolkien, while acknowledging as correct the Northern Germanic conception of humanity’s final powerlessness before the greater strength of wyrd as fate, uses the person’s ultimate weakness before wyrd as the means for the vindication of providence. Tolkien’s unique presentation of world order pays tribute to the pagan view of fate while transforming it into a Catholic understanding of providence. The first section of the dissertation shows how the conflict between fate and providence in The Silmarillion results from the elvish narrator’s perspective on temporal events. Chapter One examines the friction between fate and free will within The Silmarillion and within Tolkien’s Northern sources, specifically the Norse Eddas, the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, and the Finnish The Kalevala. Chapter Two shows that Tolkien, following Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, presents Middle-earth’s providential order as including fated elements but still allowing for human freedom. The second section shows how The Lord of the Rings reflects but resolves the conflict in The Silmarillion between fate, providence, and free will. -

Finnish Drama in Chinese Translation

FINNISH KULLERVO AND CHINESE KUNGFU Chapman Chen Project funded by Finnish Literature Information Center Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract Introduction: There are many important Finnish plays but, due to language barrier, Finnish drama is seldom exported, particularly to Hong Kong and China.. Objective: To find out differences in mentality between the Finnish and Chinese peoples by comparing the partially localized Chinese translation of Aleksis Kivi’s tragedy, Kullervo, with genuine Chinese martial arts literature. Methodology: 1. Chapman Chen has translated the Finnish classic, Kullervo, directly from Finnish into Chinese and published it in 2005. 2. In Chen’s Chinese translation, cultural markers are domesticated. On the other hand, values, characterization, plot, and rhythm remain unchanged. 3. According to Gideon Tory, the translator has to strike a golden mean between the norms of the source language and the target language. 4. Lau Tingci lists and explicates the essential components of martial arts drama. 5. According to Ehrnrooth’s “Mentality”, equality is the most important value in Finnish culture. Findings: i. Finland emphasizes independence while China emphasizes bilateral relationships. ii. The Finnish people loves freedom, but Gai Sizung argues that the Chinese people is slavish. iii. Finns are mature while many Chinese are, according to Sun Lung-kee (“The Deep Structure of Chinese Culture”; “The Deep Structure of Chinese Sexuality”), fixated at the oral and anal stages. iv. Finnish society highly values equality while Chinese interpersonal relationships are extremely complicated and hierachical. If Kullervo were a genuine Chinese kungfu story, the plot would be much more convoluted. Conclusion: The differences between Finnish and Chinese mentalities are so significant that partially localized or adapted Chinese translations of Finnish drama may still be able to introduce Finnish culture to the Chinese audience. -

And Estonian Kalev

Scandinavian Kalf and Estonian Kalev HILDEGARD MUST OLD ICELANDIC SAGAStell us about several prominent :men who bore the name Kalfr, Kalfr, etc.1 The Old Swedish form was written as Kalf or Kalv2 and was a fairly common name in Viking-age Scandinavia. An older form of the same name is probably kaulfR which is found on a runic stone (the Skarby stone). On the basis of this form it is believed that the name developed from an earlier *Kaoulfr which goes back to Proto-Norse *KapwulfaR. It is then a compound as are most of old Scandinavian anthroponyms. The second ele- ment of it is the native word for "wolf," ON"ulfr, OSw. ulv (cf. OE, OS wulf, OHG wolf, Goth. wulfs, from PGmc. *wulfaz). The first component, however, is most likely a name element borrowed from Celtic, cf. Old Irish cath "battle, fight." It is contained in the Old Irish name Cathal which occurred in Iceland also, viz. as Kaoall. The native Germ.anic equivalents of OIr. cath, which go back to PGmc. hapu-, also occurred in personal names (e.g., as a mono- thematic Old Norse divine name Hr;or), and the runic HapuwulfR, ON Hr;lfr and Halfr, OE Heaouwulf, OHG Haduwolf, Hadulf are exact Germanic correspondences of the hybrid Kalfr, Kalfr < *Kaoulfr. However, counterparts of the compound containing the Old Irish stem existed also in other Germanic languages: Oeadwulf in Old English, and Kathwulf in Old High German. 3 1 For the variants see E. H. Lind, Nor8k-i8liind8ka dopnamn och fingerade namn fran medeltiden (Uppsala and Leipzig, 1905-15), e. -

The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot's Kalevala

Oral Tradition, 8/2 (1993): 247-288 From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala1 Thomas DuBois The question of Elias Lönnrot’s role in shaping the texts that became his Kalevala has stirred such frequent and vehement debate in international folkloristic circles that even persons with only a passing interest in the subject of Finnish folklore have been drawn to the question. Perhaps the notion of academic fraud in particular intrigues those of us engaged in the profession of scholarship.2 And although anyone who studies Lönnrot’s life and endeavors will discover a man of utmost integrity, it remains difficult to reconcile the extensiveness of Lönnrot’s textual emendations with his stated desire to recover and present the ancient epic traditions of the Finnish people. In part, the enormity of Lönnrot’s project contributes to the failure of scholars writing for an international audience to pursue any analysis beyond broad generalizations about the author’s methods of compilation, 1 Research for this study was funded in part by a grant from the Graduate School Research Fund of the University of Washington, Seattle. 2 Comparetti (1898) made it clear in this early study of Finnish folk poetry that the Kalevala bore only partial resemblance to its source poems, a fact that had become widely acknowledged within Finnish folkoristic circles by that time. The nationalist interests of Lönnrot were examined by a number of international scholars during the following century, although Lönnrot’s fairly conservative views on Finnish nationalism became equated at times with the more strident tone of the turn of the century, when the Kalevala was made an inspiration and catalyst for political change (Mead 1962; Wilson 1976; Cocchiara 1981:268-70; Turunen 1982). -

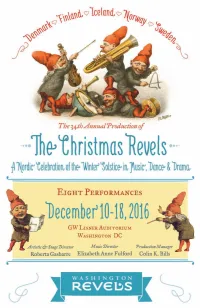

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles.