Birmingham to Inform the New Partnership Between Birmingham, UK and Pune, India on Smart Nutrition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

33 Birmingham

33 Birmingham - Pheasey via Perry Barr Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Carrs Lane (Stop BS16) 0500 0540 0600 0617 0633 0650 0700 0710 0720 0730 0740 0750 0800 0810 0820 0830 Newtown, Six Ways Aston (near) 0510 0550 0610 0627 0644 0701 0711 0721 0731 0742 0752 0802 0812 0822 0832 0842 Aldridge Road (Stop T2) 0434 0514 0529 0554 0614 0631 0648 0706 0716 0726 0736 0747 0757 0807 0817 0827 0837 0847 Birmingham City University, Wellhead Lane 0436 0516 0531 0556 0616 0633 0650 0708 0718 0728 0738 0749 0759 0809 0819 0829 0839 0849 Warren Farm, Chingford Road (before) 0442 0522 0537 0602 0622 0639 0656 0715 0725 0735 0746 0757 0807 0817 0827 0837 0847 0857 Kingstanding, Kingstanding Police Station 0448 0528 0543 0608 0628 0645 0702 0722 0732 0742 0754 0805 0815 0825 0835 0845 0855 0905 (before) Collingwood Centre (adjacent) 0453 0533 0548 0613 0633 0650 0707 0727 0737 0747 0800 0811 0821 0831 0841 0851 0901 0911 Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Carrs Lane (Stop BS16) 0840 0850 0900 0910 0920 0930 0940 0950 1000 1010 1020 1030 1040 1050 1100 1110 1120 1130 Newtown, Six Ways Aston (near) 0852 0902 0912 0922 0932 0942 0952 1002 1012 1022 1032 1042 1052 1102 1112 1122 1132 1142 Aldridge Road (Stop T2) 0858 0908 0918 0928 0938 0948 0958 1008 1018 1028 1038 1048 1058 1108 1118 1128 1138 1148 Birmingham City University, Wellhead Lane 0900 0910 0920 0930 0940 0950 1000 1010 1020 1030 1040 1050 1100 1110 1120 1130 1140 -

Birmingham Transport Plan Consultation Report June 2021

Draft Birmingham Transport Plan Consultation Report June 2021 1 1. Contents s1. Contents ......................................................................................................................... 2 2. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 4 2.1. Consultation methodology ................................................................................................ 4 2.2. Responses ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.3. Vision ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.4. Big moves ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.4.1. Reallocating road space ............................................................................................ 4 2.4.2. Transforming the city centre....................................................................................... 5 2.4.3. Prioritising active travel in local neighbourhoods ........................................................ 5 2.4.4. Managing demand through parking measures ........................................................... 5 2.4.5. Other comments ........................................................................................................ 5 2.5. COVID-19 and Emergency Birmingham Transport Plan .................................................. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

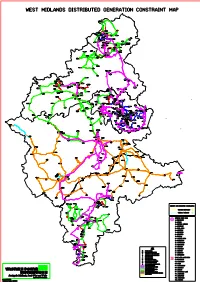

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

Birmingham, Kingstanding Branch Review Our Branch at Birmingham, Kingstanding Is Closing on 24 March 2021

Birmingham, Kingstanding Branch Review Our branch at Birmingham, Kingstanding is closing on 24 March 2021. What you need to know We’ve looked carefully at our Birmingham, Kingstanding branch at 1 Warren Farm Road, Kingstanding, Birmingham, B44 0PS and how it is used, and we’ve taken the decision to close it. The way customers bank with us is rapidly evolving with the vast majority of everyday transactions now being done digitally. Over 2.1 million of our customers now choose to bank online, and over 1.3 million use our Mobile Banking App. Even prior to COVID-19 customers were choosing other ways to bank with us, with 50% using services at our cash machines, and 20% using a Post Office®. Over 190,000 customers have been supported through our new online chat service, helping them with queries and other services. 67% of all our customers are now using mobile, online or telephone banking, and at this branch 80% of our personal and 83% of our business customers, now choose to use another branch or channel instead. We need to make sure our branches meet the current and future needs of our customers, and TSB remains committed to face to face services in branch through a network that covers the whole country. In the West Midlands we will still have 16 branches serving 344,792 customers. This Branch Review explains how we can support you through the changes and the alternative services you can use. What does this change mean for you There are a number of other branches you can visit, including Birmingham, Perry Barr below, which is 2.2 miles away from the closing branch. -

Regional Gross Value Added (Income Approach): London Leads UK Cities in Economic Recovery

Article Regional Gross Value Added (Income Approach): London leads UK cities in economic recovery Following the publication of regional Gross Value Added (income approach), this article focuses on the economic performance of the largest UK cities. We compare the cities’ annual GVA growth from 2013 to 2014, and also the longer term growth since the low- point of the recent economic downturn in 2009. For each city covered we identify the industries mostly responsible for driving this change. Contact: Release date: Next release: Trevor Fenton 10 December 2015 7 December 2016 (provisional [email protected] date) Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. London and Manchester 3. Other major UK cities 4. Background notes 5. Annex A: Local Authorities covered by the city areas used in this article Page 1 of 9 1. Introduction Since 2009, the low point of the UK’s recent economic downturn, London has seen the strongest growth in gross value added (GVA) of the major UK cities, increasing by 28.9% over the five years to 2014. Most other major UK cities have also shown growth over this period, though to a lesser extent. Greater Manchester increased by 15.2% from 2009 to 2014. The latest regional GVA figures published today by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show how the economic activity in regions, counties and cities of the UK has changed between 1997 and 2014. In this article we look at the performance of some of the largest cities in the UK, defined according to the European NUTS system. Some of these areas do not match the regions that are being established for the new City Deals, as these new administrative regions are still evolving independently of existing standards. -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities -

Local Wealth Building in Birmingham & Beyond

LOCAL WEALTH BUILDING IN BIRMINGHAM & BEYOND A NEW ECONOMIC MAINSTREAM Local Wealth Building An introduction Centre for Local Economic Strategies Local Wealth Building is a new approach CLES is the UK’s leading, independent think and do tank realising progressive to economic development that addresses economics for people and place. Our aim is to achieve social justice, good local the failure of the current agenda to generate economies and effective public services significant benefit for local economies and for everyone, everywhere. www.cles.org.uk people. Born out of a frustration with ‘development as usual’ approaches, Acknowledgements Local Wealth Building provides a practical framework for generating CLES would like to thank Barrow Cadbury and spreading wealth within communities. Trust for their continued and generous support of our work on Local Wealth Over the last decade, people across the UK have taken on local Building, with particular thanks to Clare wealth building ideas, applied them in their own communities and Payne and Debbie Pippard. witnessed the fruits of their work through the growth of inclusive, living waged jobs, invigorated local supply chains, greater concentrations We would also like to thank: all of the Anchor of local business and increased local spending. Institutions featured in this publication who are forging a new path in economic development, especially City-REDI at the This publication University of Birmingham (Rebecca Riley, Dr Tasos Kitsos and Dr Charlotte Hoole) This publication distils the learning from these places and charts a for compiling the data and analysis for course for a future in which Local Wealth Building is the mainstream of the University of Birmingham Case study; local economic development theory and practice in the UK. -

8A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8A bus time schedule & line map 8A Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise View In Website Mode The 8A bus line Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Saltley: 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8A bus arriving. Direction: Saltley 8A bus Time Schedule 49 stops Saltley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:59 AM - 11:46 PM Monday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Alum Rock Rd, Saltley Adderley Road, Birmingham Tuesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Saltley Trading Estate, Saltley Wednesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Hereford Square, Birmingham Thursday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Nechells Place, Saltley Friday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM 1 Mainstream Way, Birmingham Saturday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Goodrick Way, Nechells Green Lingard Close, Birmingham Nechells Police Station, Saltley Nechells Place, Birmingham 8A bus Info Direction: Saltley Cromwell St, Nechells Green Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 57 min Cheston Rd, Aston Line Summary: Alum Rock Rd, Saltley, Saltley William Henry street, Birmingham Trading Estate, Saltley, Nechells Place, Saltley, Goodrick Way, Nechells Green, Nechells Police Aston Cross, Aston Station, Saltley, Cromwell St, Nechells Green, Cheston 1 Rocky lane, Birmingham Rd, Aston, Aston Cross, Aston, Upper Sutton St, Aston, Selston Rd, Newtown, Alma St, Newtown, Upper Sutton St, Aston Holte School, Newtown, Lozells St, Lozells, Church Dunsfold Croft, Birmingham St, Hockley, Hockley Circus, Hockley, Barr Street, Hockley, Unett St, Hockley, -

COVID Enforcement Patrols Regular Enforcement Patrols Are Undertaken to Ensure Businesses Are Complying with Coronavirus Legislation

COVID Marshals • 25 COVID Marshals and 8 Park Marshals employed since November providing a hi-vis presence on the street. • Visiting all Wards but are particularly focusing on those with the highest infection rates. • Assisting with surge testing in Great Park and Frankley. • Providing advice to businesses on good practice and to citizens on the use of face coverings. • Eyes and ears for Enforcement Team providing valuable feedback on businesses who are not complying with the legislation so that enforcement work can be prioritised. • Large number of “free” face coverings are being distributed by the COVID Marshals on a daily basis. To date over 18,500 face coverings have been distributed. • Public interactions has now a last fallen considerably since the latest lockdown was introduced. (mid Jan-Feb) • Enclosed shopping centres found to have the highest level of non-compliance with regards to the wearing of face coverings. • Between the 16th Jan and 14th Feb the majority of face coverings (40% - 1,345) were distributed in the City Centre. • 446 masks were distributed by the Park COVID Marshals (13%). PA F 1 1 1 1 1 20 12 20 40 60 80 0 2 4 6 8 GE th 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ace J a 3 n – 14 Acocks Green th Fe Alum Rock b co ( e Aston x c lu Billesley d in v g Bordesley & Highgate L a erings d ywoo Bordesley Green Bournville & Cotteridge d ) Brandwood & King's Heath Bromford & Hodge Hill Castle Vale Erdington distri Frankley Great Park Gravelly Hill Hall Green North Hall Green South but Handsworth Handsworth Wood Harborne ed Holyhead King's Norton North b King's Norton South y w Kingstanding Longbridge & West Heath Lozells ar Moseley Newtown d b Northfield Perry Barr y CO Perry Common Pype Hayes Sheldon Small Heath VID Soho & Jewellery Quarter South Yardley Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Marshals Sparkhill Stirchley Sutton Four Oaks Sutton Mere Green Sutton Trinity Sutton Vesey Tyseley & Hay Mills Weoley & Selly Oak Yardley West & Stechford PA public No 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 12 50 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 GE th 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Jan 4 .