Western Savings Fund Society 1805-07 E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-District-Satterlee-Heights.Pdf

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC DISTRICT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. NAME OF HISTORIC DISTRICT The Satterlee Heights Historic District 2. LOCATION Please attach a map of Philadelphia locating the historic district. Councilmanic District(s): 3 3. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach a map of the district and a written description of the boundary. 4. DESCRIPTION Please attach a description of built and natural environments in the district. 5. INVENTORY Please attach an inventory of the district with an entry for every property. All street addresses must coincide with official Office of Property Assessment addresses. Total number of properties in district: 8 Count buildings with multiple units as one. Number of properties already on Register/percentage of total: 2/25% Number of significant properties/percentage of total: 8/100% Number of contributing properties/percentage of total: 0/8 Number of non-contributing properties/percentage of total: NA 6. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from 1871 to 1897. CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic district satisfies the following criteria for designation (check all that apply): (a) Has significant character, interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the City, Commonwealth or Nation or is associated with the life of a person significant in the past; or, (b) Is associated -

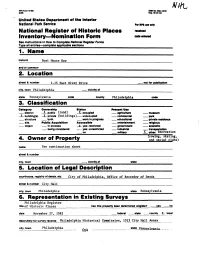

National Register of Historic Places Received Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS UM only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections ________________________ 1. Name historic Merlon Cricket Club and or common 2. Location street & number Montgomery Avenue and Grays Lane not for publication city, town Haverford vicinity of state Pennsylvania code county Montgomery code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public " occupied agriculture museum _X_ building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered ... yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X no military _X_ other: recreati 4. Owner of Property name Merlon Cricket Club (c/o Mr. Earl Vollmer, Manager) street & number Montgomery Avenue & Grays Lane____________ city, town Haverford vicinity of state Pennsylvania 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Recorder of Deeds, Montgomery County Courthouse street & number Swede and Airy Streets city, town Norristown state Pennsylvania 19401 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title None has this property been determined eligible? yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _X_ excellent __ deteriorated _ unaltered X original site good ruins X altered _ - moved date fair unex posed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Summary The Merion Cricket Club occupies a 20-acre rectangular plot just off Montgomery Avenue. -

Morris-Shinn-Maier Collection

Morris-Shinn-Maier collection MC.1191 Janela Harris and Jon Sweitzer-Lamme Other authors include: Daniel Lenahan, Kate Janoski, Jonathan Berke, Henry Wiencek and John Powers. Last updated on May 14, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Morris-Shinn-Maier collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................6 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................7 Scope and Contents..................................................................................................................................... 14 Administrative Information......................................................................................................................... 15 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................16 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 18 Historical Papers.................................................................................................................................... 18 Individuals..............................................................................................................................................23 -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

Fine Golf Books from the Library of Duncan Campbell and Other Owners

Sale 461 Thursday, August 25, 2011 11:00 AM Fine Golf Books from the Library of Duncan Campbell and Other Owners Auction Preview Tuesday, August 23, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, August 24, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, August 25, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/ realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www. pbagalleries.com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. -

Haverford College Bulletin, New Series, 7-8, 1908-1910

STACK. CLASS S ^T^J BOOK 1^ THE LIBRARY OF HAVERFORD COLLEGE (HAVERFORD, pa.) BOUGHT WITH THE LIBRARY FUND BOUND ^ MO. 3 19) V ACCESSION NO. (d-3^50 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/haverfordcollege78have HAVERFORD COLLEGE BULLETIN Vol. VIII Tenth Month, 1909 No. 1 IReports of tbe Boaro of flDanaaers Iprestoent of tbe College ano treasurer of tbe Corporation 1908*1009 Issued Quarterly by Haverford College, Haverford, Pa. Entered December 10, 1902, at Haverford, Pa., as Second Class Matter under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894 THE CORPORATION OF Haverford College REPORTS OF BOARD OF MANAGERS PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE TREASURER OF THE CORPORATION PRESENTED AT THE ANNUAL MEETING TENTH MONTH 12th, 1909 THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY PHILADELPHIA CORPORATION. President. T. Wistar Brown 235 Chestnut St., Philadelphia Secretary. J. Stogdell Stokes ion Diamond St., Philadelphia Treasurer. Asa S. Wing 409 Chestnut St., Philadelphia BOARD OF MANAGERS. Term Expires 1910. Richard Wood 400 Chestnut St., Phila. John B. Garrett Rosemont, Pa. Howard Comfort 529 Arch St., Phila. Francis Stokes Locust Ave., Germantown, Phila. George Vaux, Jr 404 Girard Building, Phila. Stephen W. Collins 69 Wall St., New York, N. Y. Frederic H. Strawbridge 801 Market St., Phila. J. Henry Scattergood 648 Bourse Building, Phila. Term Expires 1911. Benjamin H. Shoemaker 205 N. Fourth St., Phila. Walter Wood 400 Chestnut St., Phila. William H. Haines 1136 Ridge Ave., Phila. Francis A. White 1221 N. Calvert St., Baltimore, Md. Jonathan Evans "Awbury," Germantown, Phila. -

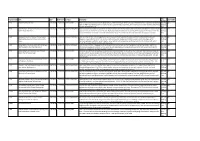

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

Morris-Shinn-Maier Collection HC.Coll.1191

Morris-Shinn-Maier collection HC.Coll.1191 Finding aid prepared by Janela Harris and Jon Sweitzer-Lamme Other authors include: Daniel Lenahan, Kate Janoski, Jonathan Berke, Henry Wiencek and John Powers This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 28, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections July 18, 2011 370 Lancaster Ave Haverford, PA, 19041 610-896-1161 [email protected] Morris-Shinn-Maier collection HC.Coll.1191 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 7 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 8 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................. 15 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................16 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................16 Collection Inventory................................................................................................................................... -

National Register of Historio Places Inventory—Nomination Form

MP8 Form 10-900 OMeMo.10M.0018 (342) Cup. tt-31-04 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historio Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Aeg/ster Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name historic Boat House Row and or common 2. Location street & number 1-15 East River Drive . not for publication city, town Philadelphia vicinity of state Pennsylvania code county Philadelphia code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __district JL public (land) _X_ occupied _ agriculture _ museum _JL building(s) JL private (buildings)__ unoccupied —— commercial —— park __ structure __ both __ work in progress —— educational __ private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accesaible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process _X- yes: restricted __ government __ scientific __ being considered _.. yes: unrestricted __ industrial —— transportation __no __ military JL. other: Recreation Trowing, skating, 4. Owner of Property and social clubs') name See continuation sheet street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. City of Philadelphia, Office of Recorder of Deeds street & number City Hall_____ _____________________________• city, town Philadelphia state Pennsylvania 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Philadelphia Register title of Historic Places yes no date November 27, 1983 federal state county JL local depository for survey records Philadelphia Historical Commission, 1313 City HaH Annex city, town Philadelphia _____.____ state Pennsylvania 65* 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent X deteriorated .. unaltered X original site good ruins X_ altered .moved date ...... -

Septa-Phila-Transit-Street-Map.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q v A Mill Rd Cricket Kings Florence P Kentner v Jay St Linden Carpenter Ho Cir eb R v Newington Dr Danielle Winding W Eagle Rd Glen Echo Rd B Ruth St W Rosewood Hazel Oak Dr Orchard Dr w For additional information on streets and b v o o r Sandpiper Rd A Rose St oodbine1500 e l Rock Road A Surrey La n F Cypress e Dr r. A u Dr Dr 24 to Willard Dr D 400 1 120 ant A 3900 ood n 000 v L v A G Norristown Rd t Ivystream Rd Casey ie ae er Irving Pl 0 Beachwoo v A Pine St y La D Mill Rd A v Gwynedd p La a Office Complex A Rd Br W Valley Atkinson 311 v e d 276 Cir Rd W A v Wood y Mall Milford s r Cir Revere A transit services ouside the City of 311 La ay eas V View Dr y Robin Magnolia R Daman Dr aycross Rd v v Boston k a Bethlehem Pike Rock Rd A Meyer Jasper Heights La v 58 e lle H La e 5 Hatboro v Somers Dr v Lindberg Oak Rd A re Overb y i t A ld La Rd A t St ll Wheatfield Cir 5 Lantern Moore Rd La Forge ferson Dr St HoovStreet Rd CedarA v C d right Dr Whitney La n e La Round A Rd Trevose Heights ny Valley R ay v d rook Linden i Dr i 311 300 Dekalb Pk e T e 80 f Meadow La S Pl m D Philadelphia, please use SEPTA's t 150 a Dr d Fawn V W Dr 80- arminster Rd E A Linden sh ally-Ho Rd W eser La o Elm Aintree Rd ay Ne n La s Somers Rd Rd S Poplar RdS Center Rd Delft La Jef v 3800 v r Horseshoe Mettler Princeton Rd Quail A A under C A Poquessing W n Mann Rd r Militia Hill Rd v rrest v ve m D p W UPPER Grasshopper La Prudential Rd lo r D Newington Lafayette A W S Lake Rd 1400 3rd S eldon v e Crestview ly o TURNPIKE A Neshaminy s o u Rd A Suburban Street and Transit Map. -

An Artistic Milestone for a Sport and a City

TRACK INSIDE REDISCOVERED: An Artistic Milestone forxcitement a among Sport scholars and a City and connoisseurs is grow- ing over what may well be the frst American art- work depicting a rowing regatta. This is not just an attractive picture, but also emblematic of a tradition distinctive to the city of Philadelphia, where the country’s frst private clubs for rowing and rac- ing boats propelled by oars were established in the early 1830s. The site of this artwork’s rediscovery is Ethe Undine Barge Club, an amateur (though very dedicated) rowing club on the Schuylkill River headquartered in a magnifcent 1882 boathouse designed by the great local architect Frank Furness. Now one of a dozen such clubs lining Boathouse Row, the Undine was founded in 1856 for “healthful exercise, relaxation from business ... and pleasure.” The lead players in the rediscovery are the painter Joseph Sweeney (b. 1950), who is artist-in-residence at the club, and James H. Hill, a longtime Undinian. Sweeney has long encouraged its members to conserve some of the historic artworks hang- ing on the walls of their house; needless to say, its essential proximity to the river brings with it signifcant humidity issues. Firmly identifed artworks have been receiving expert conserva- tion treatment, but the particular picture under approached by Dr. Lily Milroy of the Philadelphia consideration here — an easel-sized gouache Museum of Art, who was writing a book about NICOLINO VICOMPTE CALYO (1799 –1884), First on paper — does not have a signature or label, the history of the Schuylkill River. She thought Schuylkill Regatta, c. -

Wilson Eyre, 1858-1944

THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA WILSON EYRE COLLECTION (Collection 032) Wilson Eyre, 1858-1944 A Finding Aid for Architectural Drawings, 1880-1938, in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2003 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Wilson Eyre Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Architectural Drawings, 1880-1938. Coll. ID: 032. Origin: Eyre, Wilson, 1858-1944, architect. Extent: 578 original drawings, 409 mixed photomechanical reproductions and photostats, 1 rendered photostat. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: The collection comprises 987 drawings documenting 147 buildings and projects designed between 1880 and 1938 by Wilson Eyre, his predecessor James Peacock Sims (1849-1882), and his later partner John Gilbert McIlvaine (1880-1939). Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group. The record number for this collection is PAUP01-A46. Publications: Drawings in this collection have been published in the following books. Jordy, William H. Buildings on Paper: Rhode Island Architectural Drawings, 1825-1945. Providence: Bell Gallery, List Art Center, Brown University, 1982. Kornwolf, James D. M. H. Baillie Scott and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1972. O'Gorman, James F., et al.