Control and Competition: the Architecture of Boathouse Row

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PGRC Pitch Meter Spring 2012 150 Years at #14 Boathouse Row: Special Edition “First on the Row, First for Women”

Lorem Ipsum Dolor Spring 2012 Vol. 3-1 PGRC Pitch Meter Spring 2012 150 Years at #14 Boathouse Row: Special Edition “First on the Row, First for Women” Boathouse Row is intertwined with the development of Fairmount Park. The City of Philadelphia built the world’s largest dam at Fairmount to power its waterworks in 1822, forming a three-mile long slack water pond that was perfect for recreational boating. The river also froze in winter to create a generous skating rink. In 1844, the city of Philadelphia purchased Lemon Hill, a private estate just Keystone, Philadelphia Skating and Humane north of the waterworks, and in 1855 Society. Photo courtesy of E. Abrahams rededicated the property as Fairmount Park, acknowledging its popularity as a recreational The Philadelphia Skating Club and destination. Humane Society boathouse, now owned and occupied by the Philadelphia Girls’ Rowing Club at 14 Boathouse Row, is the oldest structure on Boathouse Row, itself a National Historic Landmark. It may also be one of the oldest continually occupied recreational facilities in the United States, for no comparable structures are known to have survived. History of #14 Boathouse Row Club house of the Philadelphia Skating Club and Humane Society on the Schuylkill River near Turtle Rock, Fairmount Park. From: The story of the Philadelphia Girls’ Anne C. Lewis Scrapbook. Philadelphia: 1896. The Library Company of Rowing Club’s historic headquarters at 14 Philadelphia. PGRC and Philadelphia Girlsʼ Rowing Weʼre always remembering Philadelphia Skating Club and Club former PGRC rowers! Humane Society #14 Boathouse Row Contact us via our website Invite you to Celebrate Kelly Drive th or Facebook page the 150 Anniversary Philadelphia PA 19130 of #14 Boathouse Row http://www.philadelphiagirlsrowing June 2, 2012 4 – 7 PM club.com/ Lorem Ipsum Dolor PGRC Pitch Meter Spring 2012 By this date, Philadelphians were traveling public park. -

ATHLETICS Aer4llvolltory Sale Ii I

I C THE WASHINGTON TIMES SUNDAY AUGUST 14 190 11 I S ALL ROWING PACING ATHLETICS IOOOOMllE TOUR BRIGADIER CHASES h n IS MtJV HALf OVER fOR 300 PURSES to withdraw their entry Their place was taken by Junior Potomac eight THOUSANDS SEE who were easily beaten by their own Fighters Lose Nerve club men j IP With 5000 miles of travel to their I Did you know that old BrI Is FourOared Shells II to X chasing around rings up on the Ca credit and i miles more ahead of the Senior fouroared shells Artels of MO purses now Being them a tanned and sunburned party ef imdtan circuit for Out REGATTA haiti H 7 LOCAL MAN After Put POTOMAC Baltimore walkover Potomac asked Steve DougUs the Broadway mir-¬ Wash- ¬ failing to race No official time Ornate a itomotiillste arrived in ror of fashion wm > Is better known in Intermediate eights Won by Potomac ington yesterday afternoon from Balti- ¬ theatrical circles as Truly Shattwcks 1 ii- Boat Club Washington Bocock more husband But neither the styles nor the Chase 2 Horran 3 4 C Lavigne McGovern Erne Corbett Sharkey Barber The party consists Mr C stage swerve his interest in the turf 5 S 7 Mc- of and Mrs i i ood and Jnm Craft of Every Description Ourand Britt Mueller E Wilkins Louis R Boslwlck and B C Who ever would have thought that G wan Moore coxswain horse who In colors of August ExamplesAlways in stroke Russell all of Omaha On June 23 the the w and Dempsey Are Course- Ariel Boat Club Baltimore Leroy Belmont ran second to Chacornac In the Outing Line the they started from Omaha in a giant yel- ¬ 1 IS 2 Harry -

Art Collections FP.2012.005 Finding Aid Prepared by Caity Tingo

Art Collections FP.2012.005 Finding aid prepared by Caity Tingo This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit October 01, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Fairmount Archives 10/1/2012 Art Collections FP.2012.005 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................4 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 5 Lithographs, Etchings, and Engravings...................................................................................................5 Pennsylvania Art Project - Work Progress Administration (WPA)......................................................14 Watercolor Prints................................................................................................................................... 15 Ink Transparencies.................................................................................................................................17 Calendars................................................................................................................................................24 -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

Our Monthly Record

tended tour by a considerable party of ladies and gen- tlemen was so delightful and so successful in every way that during the coming year we shall doubtless be called upon to record many more. The fall meeting of the Massachusetts Division L.A.W. was held at Worcester, on Thursday, Sep- FOR MONTH ENDING OCTOBER 30. tember 24, under the auspices of the Worcester Bicy- cle Club. The day was occupied with sports of BICYCLING AND TRICYCLING. various kinds at Lincoln Park, Lake Quinsigamond, with a sail in the afternoon, dinner being served in We are called upon this month to record a tour the pavilion. The attendance was small, though the which may justly be regarded as one of the most day proved an enjoyable one to the participants. enjoyable events of the long and successful season now closed: the ladies’ tricycle run along the North Camden (N.J.) Wheelman.—At three o’clock Shore from Malden to Gloucester, October 15. The in the afternoon of the 24th instant the last meet of tour was under the direction of Miss Minna Caroline the season was held at the Merchantville Driving Smith, who was its projector, and occupied two days, Park. The day was perfect, and wind very light. though some of the party continued the run through a Quite a large crowd of spectators was present. The third day. The participants were: Miss Minna Caroline One-mile Dash was won by T. Schaeffer, in 3m. 271/2s. The Half-mile Heat Race was also won by Smith, Mr. -

The 25-Year Club: a Kind of Homecoming 16 the Phone Book Salutes the Boathouse

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday, October 10, 1995 Volume 42 Number 7 ‘Here’s to Friendship...’ IN THIS ISSUE As Penn’s 25-Year Club held its fortieth annual dinner 2 Ben Hoyle’s Leaving; New Era Filing; last week, the traditional gathering had the air of a The First 40 Years of the Homecoming celebration: faculty and staff of all ranks, Twenty-Five Year Club those still-in-harness mingling with sometimes legend- ary retirees. Club leadership circulates throughout the 4 Same-Sex Benefits Notice campus. At left are two former chairs, Sam Cutrufello Death of Mr. Chang Plea for Attentiveness (Kelley) of Physical Plant (ret.) and Dr. Matt Stephens of Whar- COUNCIL: Charges to the Committees; ton, with the Club’s one-time secretary Maud Tracy of 5 Agenda for October 11; for the Year Alumni Records (ret.)—a founding member of the Club whose 65th anniversary with the Penn family was 6 Compass Features: Hanging Out on the Health Corner being toasted only two days after her 85th birthday. Helping Chinese Colleagues Raise Funds Below, preparing to hand out badges to this year’s 126 Welcoming 36 Mayor’s Scholars new members, are (left) Virginia Scherfel of Facilities Innovation Corner: The Paperless Office Management (ret.), and (center), Patricia Hanrahan of Student Job-Hunting on the Net International Programs, the outgoing secretary and in- Faculty-Staff Appreciation Day coming chair of the Club. In the background (wearing 10 Opportunities checked jacket) is Nora Bugis of Chemisty (ret.), the 14 Bulletins: Safety, Training, and outgoing chair. More on pages 2-3. -

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

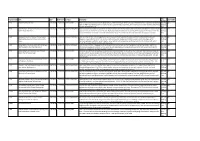

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

The University Barge Club of Philadelphia Founded 1854

THE UNIVERSITY BARGE CLUB OF PHILADELPHIA FOUNDED 1854 THIS AGREEMENT is made as of the ______ day of __________________, 20___, by and between the University Barge Club, #7 Boathouse Row, Kelly Drive, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 19130, a Pennsylvania non-profit corporation (“UBC”) and ______________________________, a member of UBC, either individually (“Bargee”) or as the sponsor, together with any person or party, to wit _____________________, (“Sponsored Party”) intending to use the Boathouse. Inasmuch as UBC enjoys the historical right to the use of the boathouse and appurtenant property at #7 Boathouse Row (hereinafter collectively “the Boathouse”), and Bargee/Sponsored Party desires to use the Lilacs Room, riverside balcony, concrete apron, dock and toilets, including those in the Member Changing Rooms, (“Public Spaces”) of the Boathouse, for social purposes, and UBC is willing to grant limited use of the Public Spaces of the Boathouse for social purposes and no other purposes of the Bargee/Sponsored Party and any of their guests (collectively “Guests”), subject to the terms and conditions set forth herein, and therefore, UBC and the Bargee/Sponsored Party agree as follows: -- Any social function party held at the Boathouse shall be conducted under the direction and control of the Bargee sponsoring the party. The sponsoring Bargee will be responsible for any and all damage caused by Guests or others invited to the Boathouse, e.g., caterers, suppliers, vendors, by the Bargee or the Sponsored Party. -- The Bargee/Sponsored Party agree to pay the fee set forth herein as provided. -- No Guests under 21 years of age will be served alcoholic beverages of any kind. -

The New Fairmount Park

THE NEW FAIRMOUNT PARK GO! HOME WHY EAST AND WEST FAIRMOUNT PARK THE BIG VISION FIRST STEPS FOCUS AREAS This improvement plan is the culmination of a Clean, safe and well-managed park year-long research, engagement and planning develop new stewardship, a united community voice process that aims to give all Philadelphians easier RT. 1 FALLS BR. access to East and West Fairmount Park—ensuring Redesign I-76 that it will thrive for generations to come. East and RIDGE AVE Resident access bring the park under the highway develop safe, attractive West Park is the heart of our park system, and its entrances to the park health is a reflection of our health. Seven million New grandstands and footbridge people use the park each year, and 1.1 million people offer better access to Peter’s Island receive water from the park, while neighborhoods Well-connected trail system from Wynnefield to Brewerytown struggle every day offer complete access for walkers with issues of park access. Signature Horticultural Center E V and bikers A offer a botanical garden in R PennPraxis based the recommendations in this E West Fairmount Park E V D I I R Improvement Plan on input from over 1,000 citizens, S L K IL R K A L with particular emphasis on park users and residents P Y U MLK DR H Overlooks Reroute Belmont Avenue C from nearby communities. An 86-organization S provide incomparable create a quieter, safer views of the park Advisory Group of park and community leaders park experience I-76 KELLY DR provided leadership and guidance throughout the process. -

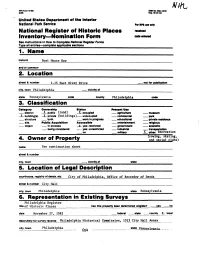

National Register of Historio Places Inventory—Nomination Form

MP8 Form 10-900 OMeMo.10M.0018 (342) Cup. tt-31-04 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historio Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Aeg/ster Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name historic Boat House Row and or common 2. Location street & number 1-15 East River Drive . not for publication city, town Philadelphia vicinity of state Pennsylvania code county Philadelphia code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __district JL public (land) _X_ occupied _ agriculture _ museum _JL building(s) JL private (buildings)__ unoccupied —— commercial —— park __ structure __ both __ work in progress —— educational __ private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accesaible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process _X- yes: restricted __ government __ scientific __ being considered _.. yes: unrestricted __ industrial —— transportation __no __ military JL. other: Recreation Trowing, skating, 4. Owner of Property and social clubs') name See continuation sheet street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. City of Philadelphia, Office of Recorder of Deeds street & number City Hall_____ _____________________________• city, town Philadelphia state Pennsylvania 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Philadelphia Register title of Historic Places yes no date November 27, 1983 federal state county JL local depository for survey records Philadelphia Historical Commission, 1313 City HaH Annex city, town Philadelphia _____.____ state Pennsylvania 65* 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent X deteriorated .. unaltered X original site good ruins X_ altered .moved date ...... -

July 9, 2018. for IMMEDIATE INTERNAL DISTRIBUTION to ALL SCHUYLKILL NAVY CLUB MEMBERS and TENANT PROGRAMS

Sent: Monday, July 9, 2018 5:26 PM To: [email protected] Subject: Re: FOR SN CLUB AND TENANT DISTRIBUTION: STATUS OF SCHUYLKILLRIVER DREDGING >>> Schuylkill Navy <[email protected]> 7/9/2018 10:25 AM >>> Schuylkill Navy Delegates and Presidents (with additional cc to Captains, SN Chairs, etc): Please find below (and attached) a comprehensive update on the status of Schuylkill River Dredging. Thanks in advance for working together (Delegates and Presidents with help from club secretaries) to ensure that 100% of all club members, tenant programs (minimally coaches and Athletic Directors (with ask that they in turn forward to parents/alums/etc),) etc. receive the update, since it contains important information regarding the now-needed pivot to "Plan B Private Funding for Restorative Dredging" as well as re-affirmation of the need for Maintenance/ Decennial Dredging to maintain the River's depth and viable use for recreation. We are all in this together, and we need our collective community to be fully up to speed as we take next steps. As always, the Schuylkill Navy's River Restoration Committee will meet this upcoming 3rd Monday of the month (July 16) at 6:00 pm. For questions or additional information, please reach out to River Restoration Committee Chair Paul Laskow at [email protected] Best, Bonnie Vice Commodore 215-815-0599 July 9, 2018. FOR IMMEDIATE INTERNAL DISTRIBUTION TO ALL SCHUYLKILL NAVY CLUB MEMBERS AND TENANT PROGRAMS. STATUS OF SCHUYLKILL RIVER DREDGING Executive Summary: • Despite significant support from all needed municipal and federal political figures as well as the local US Army Corps of Engineers (US ACE Philadelphia District Office), there is no funding for dredging at Boathouse Row nor the National Course on the Schuylkill River in the US ACE 2019 Work Plan. -

Tlu Lictutstilnatttatt ^ W T? Fmmrlrrl 1885

tlu lictutstilnatttatt ^ W T? fmmrlrrl 1885 ■•■''' lily . , , Vol. \CIX.\o.6l I'llll AHHPHIA.July I. 1983 Minority admissions fall in larger Class of 1987 Officials laud geographic diversity B> I -At KfN ( (II I MAN the) are pleased with the results ol a \ target class ol 1987 contains dtive 10 make the student bod) more liginificantl) fewei minority geographicall) diverse, citing a students but the group is the Univer- decrease in the numbet ol students sity's most geographicall) diverse from Ihe Northeast in the c lass ol class ever. 198". A- ol late May, 239 minority ot the 4191 students who were at -indents had indicated the) will cepted to the new freshman class. matriculate at the i niversit) in the 2178 indicated b) late \lav that the) fall as members ol the new will matricualte, a 4" percent yield. freshman class, a drop ol almost 5 Provost l hi'ina- Ehrlich said that percent from last year's figure of increasing geographic diversit) i- 251. one ol the I Diversity's top goal-. Acceptances from t hicano and "I'm ver) pleased particularl) in Asian students increased this vear, terms of following out goal of DP Steven Siege bin the number of Hacks and geographic diversit) while maintain- I xuhcranl tans tearing down the franklin Held goalpost! after IRC Quakers" 23-2 victor) over Harvard latino- dropped sharply. Hie new ing academic quality," he said. "The freshman class will have 113 black indicator- look veiv good." -indents, compared wilh 133 last Stetson -.ml the size ol the i lass veat a decline ol almost 16 per ol 1987 will not be finalized until cent tin- month, when adjustments are Champions But Vlmissions Dean I ee Stetson made I'm students who decide 10 Bl LEE STETSON lend oilier schools Stetson said he said the Financial MA Office i- 'Reflection oj the econom\' working to provide assistance winch plan- "limited use" ol the waiting will permit more minority students list to fill vacancies caused by an Iwentv two percent ol the class Quakers capture Ivy football crown to matriculate.