A Case Study in Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of “Sustainable Livelihood Programme Through Community Mobilization and Establishing Knowledge Resource Centre in Mazar-E-Sharif” Final Report

2013:39 Sida Decentralised Evaluation Sarah Gray Elisabeth Montgomery Evaluation of “Sustainable Livelihood Programme through Community Mobilization and Establishing Knowledge Resource Centre in Mazar-e-Sharif” Final Report Evaluation of “Sustainable Livelihood Programme through Community Mobilization and Establishing Knowledge Resource Centre in Mazar-e-Sharif ” Final Report December 2013 Sarah Gray Elisabeth Montgomery Sida Decentralised Evaluation 2013:39 Sida Authors: Sarah Gray and Elisabeth Montgomery The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida Decentralised Evaluation 2013:39 Commissioned by Sida - Afghanistan Unit Copyright: Sida and the authors Date of final report: December 2013 Published by Citat 2013 Art. no. Sida61667en urn:nbn:se:sida-61667en This publication can be downloaded from: http://www.sida.se/publications SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Address: S-105 25 Stockholm, Sweden. Office: Valhallavägen 199, Stockholm Telephone: +46 (0)8-698 50 00. Telefax: +46 (0)8-20 88 64 E-mail: [email protected]. Homepage: http://www.sida.se SIPU International –Final Evaluation Report Acronyms, Abbreviations and Local Terms AMA Association of Microfinance Agencies AREDP Afghanistan Rural Enterprise Development Programme CDC Community Development Council CIA Conflict Impact Assessment EIF Enterprise Incubation Fund DDH District Development Hub FGD Focus Group Discussion GDP Gross Domestic -

Access to Tazkera and Other Civil Documentation in Afghanistan NRC > AFGHANISTAN REPORT

Access to Tazkera and other civil documentation in Afghanistan NRC > AFGHANISTAN REPORT Researched and written by: Samuel Hall and the Norwegian Refugee Council Photographs: Jim Huylebroek and Farzana Wahidy Legal Editor: Sarah Adamczyk Design and layout: Chris Herwig This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union (EU) and of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). The contents of this document are solely the responsibility of the Norwegian Refugee Council and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Swedish government. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international, humanitarian non-governmental organisation which provides assistance, protection and contributes to durable solutions for refugees and internally displaced people worldwide. www.nrc.no Samuel Hall is an independent think tank providing research and strategic services, expert analysis, tailored counsel and access to local knowledge for a diverse array of actors operating in the world’s most challenging environments. samuelhall.org Acknowledgements: Thanks are due to everyone who participated in the researching and drafting of this report, in particular the staff from Samuel Hall and from NRC’s Information, Counselling and Legal Assistance (ICLA) programme in Afghanistan. Particular thanks go to Dominika Kronsteiner, Mohammad Abdoh, Ezzatullah Raji, Christopher Nyamandi, Dan Tyler, Kirstie Farmer, Monica Sanchez Bermudez and Dimitri Zviadadze. Samuel Hall would like to thank Marion Guillaume, Nassim Majidi, Ibrahim Ramazani and Abdul Basir Mohmand. NRC also wishes to thank the individuals who participated in the focus group discussions and interviews, and who shared their personal experiences for this research. -

National Area-Based Development Programme

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. NATIONAL AREA-BASED DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2014 Second Quarterly PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME DONORS PROJECT INFORMATION Project ID: 00057359 (NIM) Duration: Phase III (July 2009 – June 2015) ANDS Component: Social and Economic Development Contributing to NPP One and Four Strategic Plan Component: Promoting inclusive growth, gender equality and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) CPAP Component: Increased opportunities for income generation through promotion of diversified livelihoods, private sector development, and public private partnerships Total Phase III Budget: US $294,666,069 AWP Budget 2014: US $ 52,608,993 Un-Funded amount 2014: US $ 1,820,886 Implementing Partner Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) Responsible Party: MRRD and UNDP Project Manager: Abdul Rahim Daud Rahimi Chief Technical Advisor: Vacant Responsible Assistant Country Director: Shoaib Timory Cover Photo: Kabul province, Photo Credit: | NABDP ACRONYMS ADDPs Annual District Development Plans AIRD Afghanistan Institute for Rural Development APRP Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Programme ASGP Afghanistan Sub-National Governance Programme DCC District Coordination Councils DDA District Development Assembly DDP District Development Plan DIC District Information Center ERDA Energy for Rural Development of Afghanistan GEP Gender Empowerment Project IALP Integrated Alternative Livelihood Programme IDLG Independent Directorate of Local Governance KW Kilo Watt LIDD Local Institutional Development Department MHP Micro Hydro Power MoF Ministry of Finance MoRR Ministry of Refuge and Repatriation MRRD Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development NABDP National Area Based Development Programme PEAC Provincial Establishment and Assessment Committees RTD Rural Technology Directory RTP Rural Technology Park PMT Provincial Monitoring Teams UNDP United Nations Development Programme SPVHS Solar Photovoltaic Voltage Home System SDU Sustainable Development Unit TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Chronology of Events in Afghanistan, September 2003*

Chronology of Events in Afghanistan, September 2003* September 2 Civilian injured in grenade attack in Jalalabad. (Pakistan-based Afghan Islamic Press news agency / AIP) Unidentified people have attacked the Jalalabad judicial department with two grenades in Jalalabad, Nangarhar Province. The department was not damaged, but a man who was going to a mosque to pray was wounded. September 3 Two killed, 10 injured in attack on marriage ceremony in Nangarhar Province. (Radio Afghanistan) Two people were killed and 14 injured in a bomb attack on a wedding ceremony in Dago Village in Chaparhar District of Nangarhar Province Eight killed in clashes between tribes in Nangarhar Province. (Radio Afghanistan) The commander of Military Corps No 1 of Nangarhar Haji Hazart Ali said eight people had been killed in a clash between two tribes in Hesarak District. Two senior commanders killed in ambush in Logar Province. (Iranian radio Voice of the Islamic Republic of Iran) Two senior commanders of Logar Province, sons of a Logar-based commander named Golhayder, were killed in the ambush by unknown armed people and in the attack on a car. September 4 UN criticises 'excessive force' in Kabul evictions. (Agence France Presse / AFP) The United Nations criticised the "excessive use of force" by police in evicting 30 families and bulldozing their homes in Kabul on September 3. Some 30 families were evicted from their homes in Shir Pur village near the upmarket Wazir Akbar Khan district of central Kabul, UN spokesman Manoel de Almeida e Silva said. "According to the residents and witnesses the chief of police of Kabul (Basir Salangi) himself led the operation," de Almeida e Silva said. -

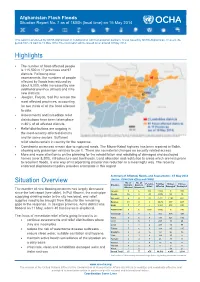

Highlights Situation Overview

Afghanistan Flash Floods Situation Report No. 7 as of 1800h (local time) on 15 May 2014 This report is produced by OCHA Afghanistan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by OCHA Afghanistan. It covers the period from 24 April to 15 May 2014. The next report will be issued on or around 20 May 2014. Highlights The number of flood-affected people is 115,500 in 17 provinces and 97 districts. Following new assessments, the numbers of people affected by floods has reduced by about 6,000, while increased by one additional province (Khost) and nine new districts. Jawzjan, Faryab, Sari Pul remain the most affected provinces, accounting for two thirds of all the flood affected to date. Assessments and immediate relief distributions have been taken place in 80% of all affected districts. Relief distributions are ongoing in the most-recently affected districts and for some sectors. Sufficient relief stocks remain in country for the response. Constraints on access remain due to ruptured roads. The Mazar-Kabul highway has been repaired in Balkh, allowing only passenger vehicles to use it. There are no material changes on security related access. More and more attention is on the planning for the rehabilitation and rebuilding of damaged and destroyed homes (over 8,300), infrastructure and livelihoods. Land allocation and restitution to areas which are less prone to recurrent floods, is one way of incorporating disaster risk reduction in a meaningful way. The recently endorsed displacement policy provides a template in this regard. Summary of Affected, Needs, and Assessments ‐ 15 May 2014 (Source: OCHA field offices and PDMC) Situation Overview No. -

End of Year Report (2018) About Mujahideen Progress and Territory Control

End of year report (2018) about Mujahideen progress and territory control: The Year of Collapse of Trump’s Strategy 2018 was a year that began with intense bombardments, military operations and propaganda by the American invaders but all praise belongs to Allah, it ended with the neutralization of another enemy strategy. The Mujahideen defended valiantly, used their chests as shields against enemy onslaughts and in the end due to divine assistance, the invaders were forced to review their war strategy. This report is based on precise data collected from concerned areas and verified by primary sources, leaving no room for suspicious or inaccurate information. In the year 2018, a total of 10638 attacks were carried out by Mujahideen against invaders and their hirelings from which 31 were martyr operations which resulted in the death of 249 US and other invading troops and injuries to 153 along with death toll of 22594 inflicted on Kabul administration troops, intelligence operatives, commandos, police and Arbakis with a further 14063 sustaining injuries. Among the fatalities 514 were enemy commanders killed and eliminated in various attacks across the country. During 2018 a total of 3613 vehicles including APCs, pickup trucks and other variants were destroyed along with 26 aircrafts including 8 UAVs, 17 helicopters of foreign and internal forces and 1 cargo plane shot down. Moreover, a total of 29 district administration centers were liberated by the Mujahideen of Islamic Emirate over the course of last year, among which some were retained -

World Bank Documents

Procurement Plan 1. Project information: Irrigation restoration and development project (P122235), Afghanistan Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan [4 december 2017 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: 18 months 5. Short list comprising entirely of national consultants: Short list of consultants for services, estimated to cost less than $200,000 equivalent per contract, may comprise entirely of national consultants in accordance with the provisions of paragraph 2.7 of the Consultant Guidelines. Public Disclosure Authorized This is not a complete procurement plan. Th actual PP will be added soon. Incase of knowing the project procurement plan please visit www.worldbank.org and search Project appraisal documents. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PROCUREMENT Afghanistan : AF Irrigation Restoration and Development Project PLAN General Information Country: Afghanistan Banks Approval Date of the Original Procurement Plan: 2017-09-20 Revised Plan Date(s): (comma delineated, leave blank if none) 2018-08-14 Project ID: P122235 GPN Date: Project Name: AF Irrigation Restoration and Development Project Loan / Credit No: IDA / H6810, TF / 12029 Executing Agency(ies): Ministry of Energy and Water [MEW] WORKS Activity Reference No. / Bid Evaluation Report Procurement Prequalification Estimated Actual Amount Process Draft Pre-qualification Prequalification Draft Bidding Document Specific Procurement Bidding Documents as Proposal Submission / -

Investigation of Poultry Diseases Outbreak in Different Seasons In

International Journal of Advanced Academic Studies 2020; 2(4): 85-88 E-ISSN: 2706-8927 P-ISSN: 2706-8919 www.allstudyjournal.com Investigation of poultry diseases outbreak in different IJAAS 2020; 2(4): 85-88 Received: 13-08-2020 seasons in Shulgara district of Balkh province Accepted: 17-09-2020 Mohammad Nasim Sahab Mohammad Nasim Sahab, Ahmad Nawid Mirzad, Atiqullah Miakhil Faculty of Veterinary Science, Balkh University, Mazar-e- and Mohammad Amin Amin Sharif, Balkh, Afghanistan. Abstract Ahmad Nawid Mirzad Understanding the occurrence of diseases will help to plan disease prevention effectively. Therefore, a Faculty of Veterinary Science, field study was conducted to describe the occurrence of various broiler diseases in Sholgara district of Balkh University, Mazar-e- Balkh province of Afghanistan. This research was conducted in 42 broiler farms of the study area. Sharif, Balkh, Afghanistan. Totally, 537 cases of broiler diseases were recorded and subjected to diagnose. Disease diagnosis was made based on history, clinical signs, and results from postmortem lesions and findings. Occurrence of Atiqullah Miakhil Faculty of Veterinary Science, CRD was the highest one (23%) in broiler chickens followed by coccidiosis (18%), salmonellosis Balkh University, Mazar-e- (12%), ND (10%), enteritis (9%), E. coli infections (7%), IBD, IB (7%), necrotic enteritis (6%) and BP Sharif, Balkh, Afghanistan. (1%). Therefore, it is recommended to apply adequate and effective vaccination practices, brooding arrangements, and good sanitation and hygiene, and biosecurity measures. Mohammad Amin Amin Faculty of Agriculture, Keywords: Poultry disease, Broiler, Shulgara, Afghanistan. Department of animal science, Badakhshan University of Introductions Afghanistan. Afghanistan economic system greatly rely on agriculture and livestock. -

Afghanistan: out of Sight, out of Mind: the Fate of the Afghan Returnees

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of this report .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Map of Afghanistan ......................................................................................... 5 2. Pattern of displacement and return in 2003 ............................................................ 6 3. Return from neighbouring states – the issue of voluntariness ................................. 8 3.1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Pakistan ........................................................................................................... 9 3.3 Iran ................................................................................................................ 10 3.3.1 Human rights abuses of Afghans in Iran .................................................. 10 3.3.2 Forced returns from Iran......................................................................... 11 4. Non-neighbouring states – forced return and promotion of assisted returns .......... 11 Forced returns from the UK ............................................................................. 13 5. IDPs – voluntariness of return and forced return ................................................. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation - Update May 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation - Update May 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN : 978-92-9494-860-1 doi: 10.2847/248967 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT AFGHANISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION – UPDATE — 3 Acknowledgements This report was largely based on information provided by the Austrian COI Department and EASO would like to acknowledge the Austrian Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum for this. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: Belgium, Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Cedoca - Center for Documentation and Research, Denmark, The Danish Immigration Service, Section Country of Origin Information, France, Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless persons (OFPRA), Information, Documentation and Research Division, Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum International and EU Affairs, COI unit, Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation, Sweden, Swedish Migration Agency, Lifos – Centre for Country of Origin Information and Analysis. Reference is made to the Disclaimer regarding the responsibility of reviewers. -

THE ANSO REPORT -Not for Copy Or Sale

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 74 16-31 May 2011 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-7 In the CENTRAL RE- Kumri while night raids and effectively to repel attacks 8-15 Northern Region GION, a lone BBIED man- ‘reintegration's’ occur else- in Mano Gai. In NAN- Western Region 16-18 aged to penetrate a military where. In JAWZJAN, GAHAR, NGO staff are hospital in KABUL, killing 6, AOG target cell phone arrested by IMF and threat- Eastern Region 19-24 despite a generally improved towers and establish vehicle ened by AOG while a sub- Southern Region 25-28 level of ANSF capacity. In check posts on the Shiber- stantial SVBIED kills 15 in WARDAK, the migration of gan-Sar-i-Pul road. In SAR- an attack on the Regional 29 ANSO Info Page Kuchis caused tension in I-PUL itself, AOGs target Training Centre. In NURI- Daymirdad while in Nirkh ANP and militias in Sayyad. STAN, a major AOG forc- IEA and HIG came to In the WESTERN RE- es captures Do Ab district. YOU NEED TO KNOW blows. In LOGAR, local GION, on May 30th a Up to 150 persons– includ- AOGs stole equipment from combination of suicide ing ANSF and civilians– • General Daoud killed in deminers while in PARWAN are killed in IMF airstrikes explosion in Takhar bombers, IEDs and infan- ANSF operations in the try engaged the PRT in HE- to recapture it. -

National Area-Based Development Programme 2014

NATIONAL AREA-BASED DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2014 ANNUAL PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME DONORS PROJECT INFORMATION Project ID: 00057359 (NIM) Duration: Phase III (July, 2009 – June, 2015) Strategic Plan Component: Promoting inclusive growth, gender equality and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) CPAP Component: Increased opportunities for income generation through promotion of diversified livelihoods, private sector development, and public private partnerships ANDS Component: Social and Economic Development Total Project Budget: USD $294,666,069 Annual Budget 2014: USD $53,384,064 Un-Funded Amount: USD $1,820,886 Implementing Partner: Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) Responsible Agency: MRRD and UNDP Project Manager: Shoaib Khaksari – Acting PM Chief Technical Advisor: Vacant Responsible Assistant Country Director: Shoaib Timory COVER PAGE: Participants in a Women’s Economic Empowerment Project in the AliceGhan settlement for Internally Displaced Persons learning embroidery| Qarabagh district, Kabul province. Photo credit: NABDP © 2014 ACRONYMS ADDPs Annual District Development Plans AIRD Afghanistan Institute for Rural Development APRP Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Programme ASGP Afghanistan Sub-National Governance Programme CDC Community Development Council CLDD Community Lead Development Department DCC District Coordination Councils DDA District Development Assembly DDP District Development Plan DIC District Information Center ERDA Energy for Rural Development