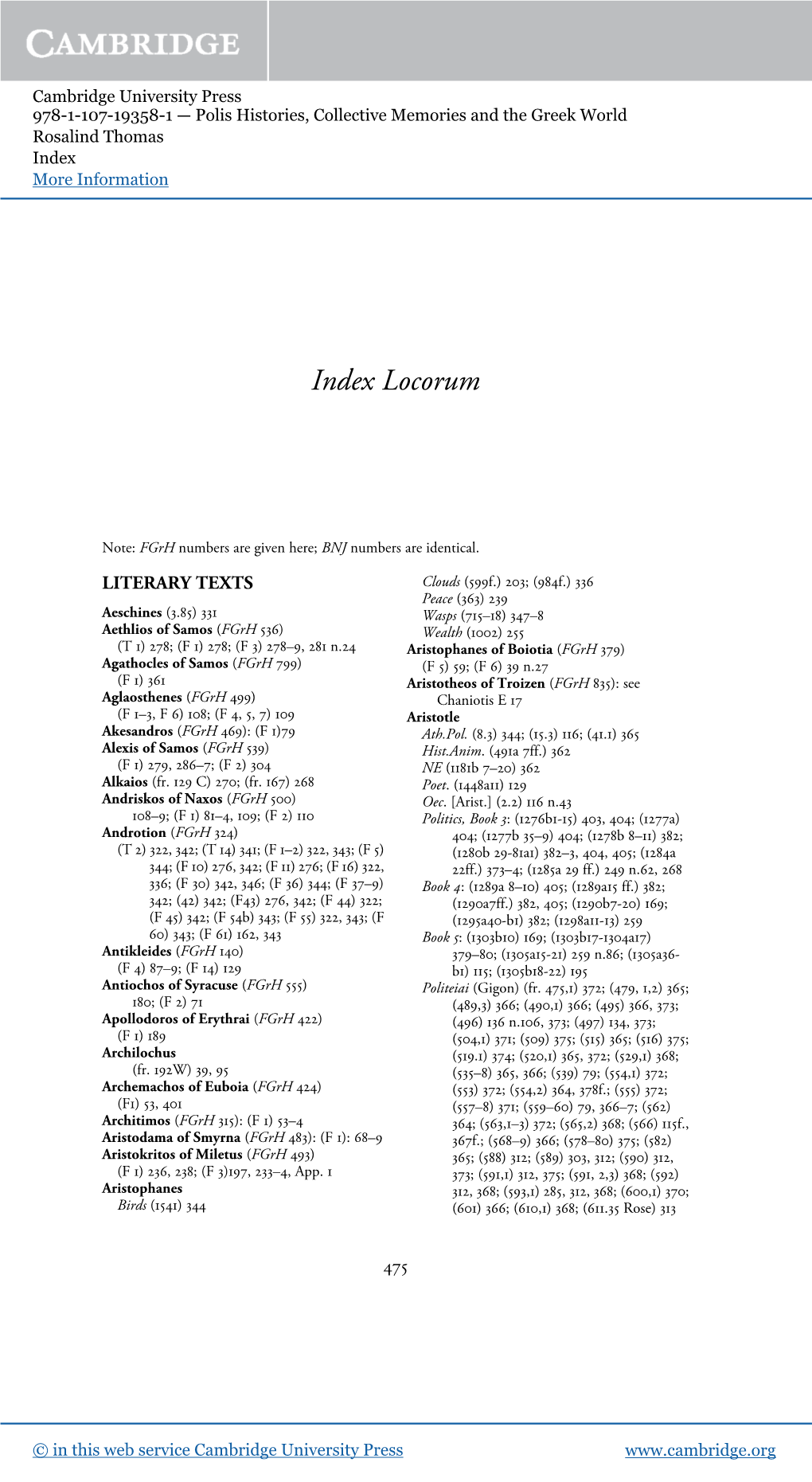

Index Locorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collins Magic in the Ancient Greek World.Pdf

9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page i Magic in the Ancient Greek World 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page ii Blackwell Ancient Religions Ancient religious practice and belief are at once fascinating and alien for twenty-first-century readers. There was no Bible, no creed, no fixed set of beliefs. Rather, ancient religion was characterized by extraordinary diversity in belief and ritual. This distance means that modern readers need a guide to ancient religious experience. Written by experts, the books in this series provide accessible introductions to this central aspect of the ancient world. Published Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins Religion in the Roman Empire James B. Rives Ancient Greek Religion Jon D. Mikalson Forthcoming Religion of the Roman Republic Christopher McDonough and Lora Holland Death, Burial and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt Steven Snape Ancient Greek Divination Sarah Iles Johnston 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iii Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iv © 2008 by Derek Collins blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Derek Collins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

A God Why Is Hermes Hungry?1

CHAPTER FOUR A GOD WHY IS HERMES HUNGRY?1 Ἀλλὰ ξύνοικον, πρὸς θεῶν, δέξασθέ με. (But by the gods, accept me as house-mate) Ar. Plut 1147 1. Hungry Hermes and Greedy Interpreters In the evening of the first day of his life baby Hermes felt hungry, or, more precisely, as the Homeric Hymn to Hermes in which the god’s earliest exploits are recorded, says, “he was hankering after flesh” (κρειῶν ἐρατίζων, 64). This expression reveals only the first of a long series of riddles that will haunt the interpreter on his slippery journey through the hymn. After all, craving for flesh carries overtly negative connotations.2 In the Homeric idiom, for instance, the expression is exclusively used as a predicate of unpleasant lions.3 Nor does it 1 This chapter had been completed and was in the course of preparation for the press when I first set eyes on the important and innovative study of theHymn to Hermes by D. Jaillard, Configurations d’Hermès. Une “théogonie hermaïque”(Kernos Suppl. 17, Liège 2007). Despite many points of agreement, both the objectives and the results of my study widely diverge from those of Jaillard. The basic difference between our views on the sacrificial scene in the Hymn (which regards only a section of my present chapter on Hermes) is that in the view of Jaillard Hermes is a god “who sac- rifices as a god” (“un dieu qui sacrifie en tant que dieu,” p. 161; “Le dieu n’est donc, à aucun moment de l’Hymne, réellement assimilable à un sacrificateur humain,” p. -

Hekate : Her Role and Character in Greek Literature from Before the Fifth

HEKATE : HER ROLE AND CHARACTER IN GREEK LITERATURE FROM BEFORE THE FIFTH CENTURY B.C. HEKATE : HER ROLE AND CHARACTER IN GREEK LITERATURE FROM BEFORE THE FIFTH CENTURY B.C. by CAROL M. MOONEY, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University February, 1971 MASTER OF ARTS (1971) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Classics) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Hekate: Her Role and Character in Greek Literature from before the Fifth Century B.C. AUTHOR: Carol M. Mooney, B.A. (Bishop's University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. T. F. Hoey NUMBER OF PAGES: iv; 96 SCOPE ~~ CONTENTS: This is a discussion of Hekate as she is repre sented in the Theogony and the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. In it I attempt to demonstrate that the more familiar sinister aspects of the goddess are not present in her early Greek form, as the literary evidence of the period reveals. This involves an inquiry into the problem of Hekate's original homeland and, as far as can be determined, her character there, as well as the examination of her role in each of the above mentioned poems and a discussion of the possi bility that the passages dealing with Hekate are interpolated. ii Acknowledgements I wish to express my warmest thanks to Dr. T. F. Hoey, my supervisor, for his helpful guidance and encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis and to Professor H. F. Guite for reading the script and offering many valuable suggestions and comments. Also I would like to thank Alan Booth for his assistance in the reading of German texts and Miss E. -

SUN MYTHS and RESURRECTION MYTHS. THERE Is a Type Of

SUN MYTHS AND RESURRECTION MYTHS. THERE is a type of resurrection myth, originating in Thrace and in North Greece, the connexion of which with the sun and moon worship is at present unduly set aside in favour of the Demeter-Persephone derivation. This type is seen in the stories, so popular in the art and drama of fifth century Athens, of the wife or husband who prevails against death, for a time at least, by recovering the beloved one. The most famous examples form a triad which is frequently mentioned, the tales of Laodamia, Alcestis, and Orpheus. The beautiful slab representing Orpheus and Eurydice at the fatal moment when restitit, Eurydicenque stiam iam luce sub ipsa immemor heu victusque animi respexit was made no doubt under the influence of the great Parthenon sculpture and very possibly about the time of the production of the Alcestis of Euripides in 438.1 Indeed in the Alcestis (348 ff.) there is one passage in which the three myths are linked. There is a reference to the plot of the Protesilaos of Euripides in the use of the image-motive, immediately followed by a reference to the journey of Orpheus. I quote the translation by Gilbert Murray:— ' O, I shall find some artist wondrous wise Shall mould for me thy shape, thine hair, thine eyes, And lay it in thy bed; and I will lie Close, and reach out mine arms td thee and cry Thy name into the night and wait and hear My own heart breathe; " Thy love, thy love is near." A cold delight; yet it might ease the sum Of sorrow . -

The Liminal and Universal: Changing Interpretations of Hekate

The Liminal and Universal: Changing Interpretations of Hekate Adrienne Ou University of California, Los Angeles Political Science and Classical Civilization Class of 2016 Abstract: Hekate is considered one of the most enigmatic figures of Greek religion. In the Theogony, she is referred to as a universal goddess. Nevertheless, her figure transforms into that of a chthonic figure, associated with witchcraft and the restless dead. This paper examines how Hekate’s role in the Greek pantheon has changed over time, and with what figures she has been syncretized or associated with in order to bring about such changes. In doing so, three images of the same goddess emerge: Hekate the universal life-bringing deity, Hekate the liminal goddess of the crossroads, and Hekate the chthonic overseer of witchcraft and angry spirits. INTRODUCTION Hekate is an enigmatic figure in Greco-Roman mythology, having evolved over the centuries from a universal deity to a chthonic figure. Due to the Greco-Roman practice of religious syncretism, her figure has taken on aspects of other gods. Likewise, other gods have absorbed some aspects originally attributed to her. Consequentially, she has many aspects and is associated with different deities. This is emphasized by the fact that as a goddess of liminality, she not only separates realms lorded over by different gods, but serves as a transition goddess for said realms. Therefore she links gods together, functioning as the sinew of the cosmos. Ergo, Hekate should not be viewed as a single figure but rather as a tripartite figure that has evolved over time. I will first discuss her origins and her role as an all-giving universal deity in Asia Minor, in the Theogony, and in the Chaldean Oracles. -

THE ENDURING GODDESS: Artemis and Mary, Mother of Jesus”

“THE ENDURING GODDESS: Artemis and Mary, Mother of Jesus” Carla Ionescu A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HUMANITIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2016 © Carla Ionescu, 2016 ii Abstract: Tradition states that the most popular Olympian deities are Apollo, Athena, Zeus and Dionysius. These divinities played key roles in the communal, political and ritual development of the Greco-Roman world. This work suggests that this deeply entrenched scholarly tradition is fissured with misunderstandings of Greek and Ephesian popular culture, and provides evidence that clearly suggests Artemis is the most prevalent and influential goddess of the Mediterranean, with roots embedded in the community and culture of this area that can be traced further back in time than even the arrival of the Greeks. In fact, Artemis’ reign is so fundamental to the cultural identity of her worshippers that even when facing the onslaught of early Christianity, she could not be deposed. Instead, she survived the conquering of this new religion under the guise of Mary, Mother of Jesus. Using methods of narrative analysis, as well as review of archeological findings, this work demonstrates that the customs devoted to the worship of Artemis were fundamental to the civic identity of her followers, particularly in the city of Ephesus in which Artemis reigned not only as Queen of Heaven, but also as Mother, Healer and Saviour. Reverence for her was as so deeply entrenched in the community of this city, that after her temple was destroyed, and Christian churches were built on top of her sacred places, her citizens brought forward the only female character in the new ruling religion of Christianity, the Virgin Mary, and re-named her Theotokos, Mother of God, within its city walls. -

Tu S F Anc W Rl 007 S Die O the Ient O D 6

TU S F ANC W RL 007 S DIEO THE IENT O- 6 D 2 - 7/2006 STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD ISBN 978-80-8082-228-6 6 - 7/2006 - 2007 . Trnavská univerzita v Trnave Filozofická fakulta Universitas Tyrnaviensis Facultas Philosophica A N O D O S Studies of the Ancient World 6-7/2006-2007 T R N A V A 2008 A N O D O S Studies of the Ancient World 6-7/2006-2007 Redakčná rada/Editorial board: Prof. PhDr. Mária Novotná, DrSc., Prof. Dr. Werner Jobst, doc. PhDr. Marie Dufková, CSc., doc. PhDr. Klára Kuzmová, CSc. Výkonní redaktori/Executive editors: doc. PhDr. Klára Kuzmová, CSc., Mgr. Ivana Kvetánová, PhD. Počítačové vyhotovenie/Computer elaboration: Zuzana Turzová © Trnavská univerzita v Trnave, Filozofická fakulta Kontaktná adresa (príspevky, ďalšie informácie)/Contact address (contributions, further information): Katedra klasickej archeológie, Trnavská univerzita v Trnave, Hornopotočná 23, SK-918 43 Trnava +421-33-5939371; fax: +421-33-5939370 [email protected] Publikované s finančnou podporou Ministerstva školstva SR (Projekty: MVTS - Tur/SR/TVU/08; KEGA č. 3/5105/07; VEGA č. 1/3749/06) a Pro Archaeologia Classica. Published with financial support of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic (Projects: MVTS - Tur/SR/ TVU/08; KEGA No. 3/5105/07; VEGA No. 1/3749/06) and the Pro Archaeologia Classica. Za znenie a obsah príspevkov zodpovedajú autori. The authors are responsible for their contributions. Tlač/Printed by: GUPRESS, s.r.o., Bratislava Žiadna časť tejto publikácie nesmie byť reprodukovaná alebo rozširovaná v žiadnej forme - elektronicky či mechanicky, vrátane fotokópií, nahrávania alebo iným použitím informačného systému vrátane webových stránok, bez predbežného písomného súhlasu vlastníka vydavateľských práv. -

OF BLACKNESS in MYTHOLOGICAL NAMES Richard Buxton the Aim Of

THE SIGNIFICANCE (OR INSIGNIFICANCE) OF BLACKNESS IN MYTHOLOGICAL NAMES Richard Buxton The aim of this paper is to examine certain mythological names involving the component melas. In order to set this enquiry into context, however, I shall first look at the general opposition between melas and leukos in Greek thought. In his still useful dissertation Die Bedeutung der weissen und der schwarzen Farbe in Kult und Brauch der Griechen und Römer, Gerhard Radke conveys a message which is basically very straightforward: in rela- tion to the gods and their worship, black is negative, white positive.1 Melas is associated with the Underworld,2 with Ate,3 with death,4 with mourning.5 In keeping with this nexus of funereal associations, animals described as melas are sacrificed to powers of the Underworld and to the dead: thus at Odyssey .– Odysseus promises to dedicate an 5ϊν παμμλανα to Teiresias if he gets back safe to Ithaca, while in Colophon, according to Pausanias (..), they sacrifice a black bitch to Enodia, andmoreovertheydosoatnight.6 Leukos, by contrast, is associated not just with divinities of light such as Helios and Day—in Aeschylus’ Persians () the glorious day of the victory at Salamis is a λευκ- πωλς μρα—but with divinities in general, especially when they are conceived of as ‘favourable’: the Dioscuri, those twin saviours, ride on 1 G. Radke, Die Bedeutung der weissen und der schwarzen Farbe in Kult und Brauch der Griechen und Römer (diss. Berlin; Jena: Neuenhahn, ). P.Vidal-Naquet, “Le chasseur noir et l’origine de l’éphébie athénienne”, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations (): –, revised in Le chasseur noir: formes de pensée et formes de société dans le monde grec (Paris: Maspero, ), – () called this a ‘catalogue consciencieux’. -

Epilepsy in Ancient Greek Medicine---The Vital Step

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Seizure 2000; 9: 12–21 doi: 10.1053/seiz.1999.0332, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Epilepsy in ancient Greek medicine—the vital step JAMES LONGRIGG Formerly Reader in Ancient Philosophy & Science, University of Newcastle, UK Correspondence to: Linden Lodge, High Hamsterley Road, Hamsterley Mill, Rowlands Gill, Tyne & Wear, NE39 1HD, UK EPILEPSY IN ANCIENT GREEK MEDICINE: ‘possessed’ the sick man’s body. To do so he employed THE VITAL STEP prayers, supplications, spells and incantations. Surviv- ing Egyptial medical papyri, like the Hearst and Ebers In the opening paragraph of his book, The Falling Sick- Papyrus, consist largely of prescriptions of drugs in- ness: A History of Epilepsy from the Greeks to the Be- terspersed with magical spells which were believed to ginnings of Modern Neurology1, Temkin writes as fol- impart efficacy to the prescriptions they follow. Many lows: of the remedies prescribed contain noxious or offen- sive ingredients to make them as unpalatable as pos- Diseases can be considered as acts or sible to the possessing spirit and so give it no induce- invasions by the gods, demons, or evil ment to linger in the patient’s body. spirits, and treated by the invocation of The ancient Babylonians, too, lived in a world supposedly supernatural powers. Or they haunted by evil spirits. Whenever they fell ill they be- were considered the effects of natural lieved that they had been seized by one of these spirits. -

Macedonian Coins

COVER PAGE: Derrones, triobol 500-480 BC Philip II of Macedon, stater Pela, c.340 - c.328 BC Justin II, 40 nummi Constantinople, 569-570 AD Maja Hadji-Maneva MACEDONIA COINS AND HISTORY GUIDE THROUGH THE PERMANENT MUSEUM EXHIBITION AT NBRM Skopje, 2008 Published by: NATIONAL BANK OF THE REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA MACEDONIA: COINS AND HISTORY GUIDE THROUGH THE PERMANENT MUSEUM EXHIBITION AT NBRM Author: Maja Hadji-Maneva Translated by: Elizabeta Bakovska Photography: Vlado Kiprijanovski Graphic design and prepress: Artistika, Skopje Printed by: Nampres, Skopje © 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this book can be copied or reproduced in electronic, mechanical or any other form without written consent of the publisher. CONTENTS NUMISMATIC COLLECTION OF THE NBRM ........................................................................... 5 PAEONIAN COINS ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Coins of the Tribal Communities in Macedonia ............................................................... 6 Coins of the Paeonian Rulers .......................................................................................................... 8 MACEDONIAN COINS ............................................................................................................................ 10 Minting Activity on the Macedonian Coast ....................................................................... 10 Coins of the Macedonian Kings ................................................................................................ -

Horse and Horsemen on Classical and Hellenistic Coins in Thessaly

Horse and Horsemen on Classical and Hellenistic Coins in Thessaly Athanasios Papaioannou SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History of Macedonia February 2019 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Athanasios Papaioannou SID: 2204160011 Supervisor: Prof. Sophia Kremydi I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. February 2019 Thessaloniki - Greece 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History of Macedonia at the International Hellenic University. The horse and horsemen are common and very popular depictions in all aspects of art either in Thessaly or Macedonia. In this way, the horse was a basic element in agricultural labor and an important means of transportation until the first decades of the 20th century. Furthermore, horses were used in warfare and played a crucial role in many battles in Antiquity. They were connected to several deities and to chthonic cults during the same period. Numismatics, on the other hand, is one of the most valuable tools of archaeologists and historians for carrying out the task of unraveling the past. Through the coin types we can trace the political messages which the issuing authorities wanted to diffuse to the local and foreign user of the currency as well as the cultural and sociopolitical background of their territory. The present paper deals with the horse types on the coinages of the Thessalian and Macedonian region. -

Una Hipótesis Sobre El Culto a Enodia En El Ejército Macedonio1

GLADIUS Estudios sobre armas antiguas, arte militar y vida cultural en oriente y occidente XXXVI (2016), pp. 59-76 ISSN: 0436-029X doi: 10.3989/gladius.2016.0004 SACRIFICIOS CANINOS EN LAS JÁNDICAS: UNA HIPÓTESIS SOBRE EL CULTO A ENODIA EN EL EJÉRCITO MACEDONIO1 DOG SACRIFICES IN THE XANDICA: A HYPOTHESIS ON THE CULT OF ENNODIA IN THE MACEDONIAN ARMY POR MARIO AGUDO VILLANUEVA* RESUMEN - ABSTRACT El descuartizamiento de una perra como ceremonia de purificación previa a un combate ritual que el ejército macedonio celebraba en las Jándicas podría tener relación con el culto a la diosa Enodia, una diosa equivalente a Hécate en el entorno cultural tesalio y macedonio. A partir de los testimonios de las fuentes históricas y de los restos arqueológicos, se trata de probar esta hipótesis, en la que se plantea la posibilidad de que este ritual fuera incor- porado con los contingentes tesalios que Filipo II introdujo en el ejército macedonio en el contexto de la profunda reforma militar que implantó al llegar al poder. The dismemberment of a female dog as a purification ceremony before a ritual combat that the Macedonian army held in the Xandica, could be related to Ennodia goddess, an equivalent to Hecate in the Thessalian and Macedonian context. From the historical sources statements and the archaeological remains, we try to prove this hypothesis, in which we present the possibility that this ritual was incorporated with Thessalian troops that Philip II introduced in the Macedonian army in the context of the deep military reform developed when he came to the head of the kingdom.