New Democracy Marc BLECHER*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~ the Soviet-East European Concept of People's Democracy

~ The Soviet - East European Concept of People's Democracy The Political Situation At the end of World \Var I I the leaders of the Communist Parties of Poland, Germany, I-lungary, l{ umania, and Bulgaria returned to their countries in the baggagetrain of the l{ ed Army and assumedcontrol of the " commanding heights" of society in dcpcndence on the Soviet occupation forces.) These Communist Parties were burdened with a dual weaknessthat limited their radicalism in the initial postwar period. All faced significant , organized opposition to the consolidation of their rule, resistance being strongest in Poland and weakest in Bulgaria. This internal situation dictated a policy of gradualism, generalized by Hugh Seton-\Vatson2 as encompassing three stages: ( 1) a genuine coalition with the surviving socialist and peasant parties resting on a short-tcrm program of mutually accepted " antifascist " and " democratic " reforms (lasting until early 1945 in Bulgaria and l{ umania and until early 1947 in l Iungary); (2) a bogus coalition with the same parties, thcmselvcs increasingly dominated by Communists, implemcnting more radical social reforms and more openly suppressing the non-Communist opposition (lasting until late 1947 or early 1948); at this stage, socialism was spoken of only as a distant goal; economic planning was introduced but remained limited in scope; collectivization of agriculture was not mentioned ; (3) a monolithic regime that , having liquidated its opposition , set out to emulate the Soviet Union in " building socialism" through forced industrialization and collectivization . Anothcr aspect of the weakness of the East Europcan Communist Partics was their great dependcnce on the Soviet Union and thus thcir subordination to the broader goals of Soviet foreign policy . -

Chapter Five

CHAPTER FIVE PEOPLE’S DEMOCRACY The post-war people’s democracies that developed in Eastern Europe and China embodied the main features of the Popular Front government advocated at the Seventh Congress of the Communist International. Politically, they were based on a multi-party, parliamentary system that included all the anti-fascist elements of the wartime Fatherland Front movements. Economically, they nationalized the most vital monopolized industries and allowed smaller capitalist industries and agriculture to continue business as usual. The theoretical status of the people’s democracies, however, was obscured by uncertainty over the future relations between the USSR and the West. If the wartime alliance was to be preserved, the communists had no wish to offend anyone with loose talk of ‘dictatorship’, whether revolutionary democratic or proletarian. Consequently, until 1948 theoretical discussions of the people’s democracies were by and large phrased in ‘apolitical’ terms, and were not associated with earlier communist theses on the state. The communist theoretician Eugen Varga, for example, wrote in 1947 that the people’s democracies were “...something entirely new in the history of mankind...” (Cited in Kase, People’s Democracies, Sijthoff, Leyden, Netherlands, 1968, p.18). They allowed capitalism, and yet protected the interests of the people. In a few years, however, the theoreticians would discover that despite multi-party composition, parliamentarism and capitalism, the people’s democracies were indeed forms of “the dictatorship of the proletariat” after all. A. Eastern Europe As consideration for his outstanding theoretical contributions to the communist movement, Dimitrov was allowed to further develop the principles of the People’s Front from the vantage point of leader of the new Bulgarian state. -

Law Enforcement Intelligence: a Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies

David L. Carter, Ph.D. School of Criminal Justice Michigan State University Law Enforcement Intelligence: A Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies November 2004 David L. Carter, Ph.D. This project was supported by Cooperative Agreement #2003-CK-WX-0455 by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Points of view or opinions contained in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or Michigan State University. Preface The world of law enforcement intelligence has changed dramatically since September 11, 2001. State, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies have been tasked with a variety of new responsibilities; intelligence is just one. In addition, the intelligence discipline has evolved significantly in recent years. As these various trends have merged, increasing numbers of American law enforcement agencies have begun to explore, and sometimes embrace, the intelligence function. This guide is intended to help them in this process. The guide is directed primarily toward state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies of all sizes that need to develop or reinvigorate their intelligence function. Rather than being a manual to teach a person how to be an intelligence analyst, it is directed toward that manager, supervisor, or officer who is assigned to create an intelligence function. It is intended to provide ideas, definitions, concepts, policies, and resources. It is a primer- a place to start on a new managerial journey. Every effort was made to incorporate the state of the art in law enforcement intelligence: Intelligence-Led Policing, the National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan, the FBI Intelligence Program, the array of new intelligence activities occurring in the Department of Homeland Security, community policing, and various other significant developments in the reengineered arena of intelligence. -

International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding

The Unintended Consequences of Democracy Promotion: International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anna M. Meyerrose, M.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Alexander Thompson, Co-Advisor Irfan Nooruddin, Co-Advisor Marcus Kurtz William Minozzi Sara Watson c Copyright by Anna M. Meyerrose 2019 Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, international organizations (IOs) have engaged in unprecedented levels of democracy promotion and are widely viewed as positive forces for democracy. However, this increased emphasis on democracy has more re- cently been accompanied by rampant illiberalism and a sharp rise in cases of demo- cratic backsliding in new democracies. What explains democratic backsliding in an age of unparalleled international support for democracy? Democratic backsliding oc- curs when elected officials weaken or erode democratic institutions and results in an illiberal or diminished form of democracy, rather than autocracy. This dissertation argues that IOs commonly associated with democracy promotion can support tran- sitions to democracy but unintentionally make democratic backsliding more likely in new democracies. Specifically, I identify three interrelated mechanisms linking IOs to democratic backsliding. These organizations neglect to support democratic insti- tutions other than executives and elections; they increase relative executive power; and they limit states’ domestic policy options via requirements for membership. Lim- ited policy options stunt the development of representative institutions and make it more difficult for leaders to govern. Unable to appeal to voters based on records of effective governance or policy alternatives, executives manipulate weak institutions to maintain power, thus increasing the likelihood of backsliding. -

APA Newsletters

APA Newsletters Volume 05, Number 2 Spring 2006 NEWSLETTER ON THE BLACK EXPERIENCE FROM THE EDITORS, JOHN MCCLENDON AND GEORGE YANCY ARTICLE JOHN H. MCCLENDON III “Dr. Richard Ishmael McKinney: Historical Summation on the Life of a Pioneering African American Philosopher” BOOK REVIEW Cornel West: Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism REVIEWED BY ROBERT E. BIRT © 2006 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and the Black Experience John McClendon & George Yancy, Co-Editors Spring 2006 Volume 05, Number 2 philosophy of religion and existentialism. Birt reminisces fondly ROM THE DITORS about McKinney, disclosing that it was Richard McKinney who F E had an incredible way of teaching philosophy, transforming dry textual exegesis into a living philosophical tradition. Throughout the course of our editorship of the Newsletter, we have insisted on the significance of and need for the reconstruction of the history of African American philosophy. In the Fall 2004 issue of this Newsletter, John H. McClendon III in ARTICLES his article, “The African American Philosopher and Academic Philosophy: On the Problem of Historical Interpretation,” presented a challenge to all of us to seriously undertake the Dr. Richard Ishmael McKinney: Historical tasks of recovering the role of the African American academic philosopher. In keeping with this challenge this issue of the Summation on the Life of a Pioneering Newsletter on Philosophy and the Black Experience seeks to African American Philosopher highlight the neglected topic of the history of African American academic philosophers by focusing on the contribution and John H. McClendon III legacy of a key figure, the late Dr. -

SOCIALISM CANNOT BE BUILT in ALLIANCE with the BOURGEOISIE the Experience of the Revolutions in Albania and China Jim Washington, About 1980, USA

SOCIALISM CANNOT BE BUILT IN ALLIANCE WITH THE BOURGEOISIE The Experience of the Revolutions in Albania and China Jim Washington, about 1980, USA CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION 1 I CHINA 4 1 “New Democracy” 4 2 Four Classes in Power 6 3 Gradual and Peaceful Transition to Socialism 7 4 Liu Shao-chi and the Right Wing of the CPC 10 5 The Transformation of Industry and Commerce 13 6 The Eighth Congress of the CPC 15 7 The Decentralization of the Economy and the Wage Reform of 1956 18 8 The “Rectification” of the Party 21 9 “Contradictions Among the People” 23 II ALBANIA 26 1 The Democratic Revolution 26 2 Conciliation With or Expropriation and Suppression of the Bourgeoisie? 27 3 The Struggle Against the Titoite Revisionists 29 4 The Consolidation of Socialist Relations of Production 30 5 The Struggle Against the Soviet Revisionists 34 III THE PLA’S CRITIQUE OF “NEW DEMOCRACY” IS CORRECT 38 1 The Popularization of the Theory of “New Democracy” 38 2 Alliances with Sectors of the Bourgeoisie in National-Democratic Revolutions 39 3 The Nature of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat and the Class Struggle During 42 the Transition to Socialism IV INTRODUCTION TO PART TWO: CLASS STRUGGLE IN SOCIALIST 50 SOCIETY V LEARNING FROM THE CHINESE AND ALBANIAN EXPERIENCES 56 NOTES 58 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 INTRODUCTION The seizure of power in China by the Teng Hsiao-ping revisionist clique stunned the com- munist movement in our country. Some organizations displayed their opportunism and hastened to consolidate themselves around the increasingly open reactionary line of the Chinese Com- munist Party. -

A Critical Review of Slovo's “Has Socialism Failed?”

South African Communist Party 1990 Crisis of Conscience in the SACP: A Critical Review of Slovo’s “Has Socialism Failed?” Written: by Z. Pallo Jordan. Lusaka, February 1990. Transcribed: by Dominic Tweedie. “Has Socialism Failed?” is the intriguing title Comrade Joe Slovo has given to a discussion pamphlet published under the imprint of ‘Umsebenzi’, the quarterly newspaper of the SACP. The reader is advised at the outset that these are Slovo’s individual views, and not those of the SACP. While this is helpful it introduces a note of uncertainty regarding the pamphlet’s authority. The pamphlet itself is divided into six parts, the first five being an examination of the experience of the ‘socialist countries’, and the last, a look at the SACP itself. Most refreshing is the candour and honesty with which many of the problems of ‘existing socialism’ are examined. Indeed, a few years ago no one in the SACP would have dared to cast such a critical light on the socialist countries. “Anti-Soviet,” “anti-Communist,” or “anti- Party” were the dismissive epithets reserved for those who did. We can but hope that the publication of this pamphlet spells the end of such practices. It is clear too that much of the heart-searching that persuaded Slovo to put pen to paper was occasioned by the harrowing events of the past twelve months, which culminated in the Romanian masses, in scenes reminiscent of the storming of the Winter Palace, storming the headquarters of the Communist Party of Roumania. It beggars the term “ironic” that scenarios many of us had imagined would be played out at the end of bourgeois rule in historical fact rang down the curtain on a ‘Communist’ dictatorship! We may expect that, just as in 1956 and 1968, there will flow from many pens the essays of disillusionment and despair written by ex- communists who have recently discovered the “sterling” qualities of late capitalism. -

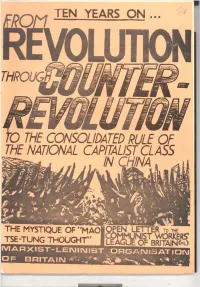

The Consolidated Rule of the National Capitalist Class in ~Na

TEN YEARS ON ... · THE CONSOLIDATED RULE OF THE NATIONAL CAPITALIST CLASS IN ~NA THE MYSTIQUE OF ''MAO _ __... TSE -TUNG THOUGHT'' I N T R 0 D U C T I 0 N THE HISTORY OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA SINCE 1966 HAS FULLY VINDICATED THE MLOBiS EXPOSuRE OF .THE COUNTER-REVOLUTIO~ARY "GREAT PROLETARIAN CULTURAL REVOLUTION" It is now almost 10 years since the Marxist-Leninist Organisation of Britain issued its historic "Report on the Situation in the People's Republic of China". This now classic analysis of the origins L s!e.yelopment and alignment of class forces in the "Great -Proletarian Cultural Revolution" of 1966-68 showed tha.b behind the demagogic mask of "socialism" in China lay: a tacTica_]J.y con:c;aled~apparatus of p ower through which- the chineE_e national- capitalist class could make its dictator ship effective in the specific conditions of a Chine. the workers and peasants of which had carried through, 17 years earlier ~ -a victu~ious national-democratic revol ution and whose revolutionary zeal and striving for fundamental social change remained at a high level. The objective situation ~n the newly-founded People's Republic of China in which, in the years immediately following the victory of the national-democratic revolution in 1949, the national capitalist class found itself, in which it was compelled to lay the first foundations of its economic system and to mould and strengthen its state apparatus of rule - the two together, base and superstructure, making up the system of "new democracy", the blueprint-for which was -

Understanding the Consequences of Neoliberalism Jenny Andersson, Olivier Godechot

Destabilizing Orders – Understanding the Consequences of Neoliberalism Jenny Andersson, Olivier Godechot To cite this version: Jenny Andersson, Olivier Godechot. Destabilizing Orders – Understanding the Consequences of Ne- oliberalism: Proceedings of the MaxPo Fifth-Anniversary Conference. Paris, January 12–13, 2018. 2018. hal-02180035 HAL Id: hal-02180035 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02180035 Preprint submitted on 11 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. No. 18/1 maxpo discussion paper Destabilizing Orders – Understanding the Consequences of Neoliberalism Proceedings of the MaxPo Fifth-Anniversary Conference Paris, January 12–13, 2018 Edited by Jenny Andersson and Olivier Godechot Jenny Andersson, Olivier Godechot (eds.) Destabilizing Orders – Understanding the Consequences of Neoliberalism: Proceedings from the MaxPo Fifth-Anniversary Conference. Paris, January 12–13, 2018 MaxPo Discussion Paper 18/1 Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies May 2018 © 2018 by the author(s) About the editors Jenny Andersson is Co-Director at the Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies (MaxPo) and CNRS Research Professor at the Center for European Studies (CEE) in Paris. Email: [email protected] Olivier Godechot is Co-Director at the Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies (MaxPo) in Paris. -

An Inversion of Radical Democracy: the Republic of Virtue in Žižek's

ISSN 1751-8229 Volume Four, Number Two An Inversion of Radical Democracy: The Republic of Virtue in Žižek’s Revolutionary Politics Geoff Boucher, Deakin University, Australia. In his most controversial recent work, In Defense of Lost Causes (hereafter IDLC), Žižek seeks to translate his critiques of the structural violence of global capitalism (Žižek, 2008b) into a programme for revolutionary action. In the series of works leading up to IDLC, Žižek has described himself as a “dialectical materialist,” albeit with a metaphysical apparatus based in Lacanian psychoanalysis that is said to supersede historical materialism. Against contemporary post-Marxian radicalism (with its exclusive focus on politics) and radical post-modernism (with its exclusive focus on culture), Žižek advocates that the radical Left should refuse to accept that capitalism “is the only game in town” (Žižek, 2000a: 95). This is combined with the injunction to “repeat Lenin” and generate the radical Act of another October 1917, although this is sometimes expressed in the bizarre vocabulary of calls for a “diabolically evil” proletarian chiliasm undertaken by “acephalous” saints (Žižek, 1997a: 79- 82; Žižek, 1997b: 228-230). In IDLC, Žižek explains that these “headless,” or driven, militants of a Jacobin-style party, modelled on quasi-suicidal samurai, would be prepared 1 to implement a “politics of universal Truth” that would break utterly with existing moral norms (Žižek, 2008a: 170, 159, 163). In a terminology borrowed from Marxism, Žižek proposes that the application of his reconceptualized notion of “class struggle,” framed by a psychoanalytic interpretation of surplus value as “surplus enjoyment” and based in an elementary antagonism between the excluded and the included, leads to a rehabilitation of the dictatorship of the proletariat. -

On Coalition Government'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 24, 1945 Mao Zedong, 'On Coalition Government' Citation: “Mao Zedong, 'On Coalition Government',” April 24, 1945, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Translation from Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Vol. 3 (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1961), 203-270. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121326 Summary: Mao Zedong defines the Chinese Communist Party's foreign policy for the post-war world, announcing that "China can never win genuine independence and equality by following the present policy of the Kuomintang government." Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation On Coalition Government April 24, 1945 I. The Fundamental Demands of the Chinese People Our congress is being held in the following circumstances. A new situation has emerged after nearly eight years of resolute, heroic and indomitable struggle waged by the Chinese people with countless sacrifices and amid untold hardships against the Japanese aggressors; in the world as a whole, decisive victory has been gained in the just and sacred war against the fascist aggressors and the moment is near when the Japanese aggressors will be defeated by the Chinese people in co-ordination with the allied countries. But China remains disunited and is still confronted with a grave crisis. In these circumstances, what ought we to do? Beyond all doubt, the urgent need is to unite representatives of all political parties and groups and of people without any party affiliation and establish a provisional democratic coalition government for the purpose of instituting democratic reforms, surmounting the present crisis, mobilizing and unifying all the anti- Japanese forces in the country to fight in effective co-ordination with the allied countries for the defeat of the Japanese aggressors, and thus enabling the Chinese people to liberate themselves from the latter's clutches. -

Rosa Luxemburg “The Accumulation of Capital”: East and West

Rosa Luxemburg “The Accumulation of Capital” and China He Ping The Department of Philosophy, Wuhan University, China E-mail: [email protected] The greatest contribution of Rose Luxemburg’s “The Accumulation of Capital” is establishment of the unified worldwide diagram of the development of capitalism in the imperialist era, which Rose Luxemburg call total capitalism. According to this diagram, only finding the market in non-capitalist countries can west capitalism realizes its accumulation of capital so that the survival of non-capitalist countries, the formation of world market and boundless enlargement of consumption are the premise of constructing world system. In chapter XXVIII of “the Accumulation of Capital”, on “The Introduction of Commodity Economy”, she cited China for her examining. Lenin was against this diagram and stressed the important role of national states in constructing world system so that he pointed out the multiple diagram of the development of capitalism in the imperialist era. All these give me a chance to discuss some problems of the relation of China to world system in different field of vision. In my paper, I am going to begin with Luxemburg’s analysis of China, and then, probe into the significance and effect of national states in the China’s modernization by examining China of the twentieth century, finally combine the two-fold character of nation states with the theory and practices of China’s modernization to discuss Luxemburg’s concepts of world history in imperialist era, and evaluate Luxemburg’s theoretical contribution and its today’s development. I. Rosa Luxemburg’s Analysis of China In “The Historical Conditions of Accumulation”of “The Accumulation of Capital”, Luxemburg said: “Modern China presents a classical example of the ‘gentle’, ‘peace-loving’ practices of commodity exchange with backward countries.