ETA Episode 73 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Theory of Three Worlds?

To All Ldn cdes From DC WHAT IS THE THEORY OF THE THREE WORLDS? Tbe;DC was asked to give a lead in the effort to better under~tand Mao Zedong's Theory.o:f the Differentiation of the Three Worlds (TTW). Th1s paper is the first . of 3 or 4 to be distributed b.~fore we hold a London . meeting on the ·subject in late November. The Nat1onal c~nference on the 1nte~ national situation is due t.o be held next June and our study on a district level will be well directed in preparation for it. In the 4 years since the Editorial Dept of the People's Daily of China brought out the booklet expounding the theory very clearly and preciseq (Foreign Languages Press 1977) . it. has come t~ occupy. a most important position iri Marxist-Leninist circles everywhere. Acceptance of the theory as a strat-egic conce.pt has become the touchstone for .Marxist-Leninists, in the same way that the realisation that th~ Soviet Union had. become an M-L basic principle in the pre-vious 110 years. It is the TTW which proved.to be the tombstone for the social-chauvinist Birchites of the CPB(M-L) and reve~led the hollowness of the adulation o•f the Bainesites of the then CPE(M-L). Thc.y categorically rejected it. At the same time, sycophants of the ne.w :theory appeared who embraced _it so tightly that the pips. squeaked. · Today it has become a line of demarcation which marks us out . ~mong all the 'left' forces in Britain. -

Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon Christian Calienes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2526 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 CHRISTIAN CALIENES All Rights Reserved ii The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon by Christian Calienes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Earth & Environmental Sciences in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Inés Miyares Chair of Examining Committee Date Cindi Katz Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Inés Miyares Thomas Angotti Mark Ungar THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes Advisor: Inés Miyares The resistance movement that resulted in the Baguazo in the northern Peruvian Amazon in 2009 was the culmination of a series of social, economic, political and spatial processes that reflected the Peruvian nation’s engagement with global capitalism and democratic consolidation after decades of crippling instability and chaos. -

Wang Guangmei and Peach Garden Experience Elizabeth J

Wang Guangmei and Peach Garden Experience Elizabeth J. Perry Introduction In the spring of 1967 China’s former First Lady Wang Guangmei was paraded onto a stage before a jeering crowd of half a million people to suffer public humiliation for her “bourgeois” crimes. Despite her repeated protestations, Wang was forced for the occasion to don a form- fitting dress festooned with a garland of ping-pong balls to mock the elegant silk qipao and pearl necklace ensemble that she had worn only a few years earlier while accompanying her husband, now disgraced President Liu Shaoqi, on a state visit to Indonesia. William Hinton (1972, pp. 103-105) describes the dramatic scene at Tsinghua University in Beijing, where the struggle session took place: A sound truck had crisscrossed the city announcing the confrontation, posters had been distributed far and wide, and over three hundred organizations, including schools and factories, had been invited. Some had sent delegations, others had simply declared a holiday, closed their doors, and sent everyone out to the campus. Buses blocked the roads for miles and the sea of people overflowed the University grounds so that loudspeakers had to be set up beyond the campus gates . At the meeting Wang [G]uangmei was asked to stand on a platform made of four chairs. She stood high enough so that tens of thousands could see her. On her head she wore a ridiculous, wide-brimmed straw hat of the kind worn by English aristocrats at garden parties. Around her neck hung a string of ping- pong balls . A tight-fitting formal gown clung to her plump body and sharp- pointed high-heeled shoes adorned her feet. -

International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding

The Unintended Consequences of Democracy Promotion: International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anna M. Meyerrose, M.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Alexander Thompson, Co-Advisor Irfan Nooruddin, Co-Advisor Marcus Kurtz William Minozzi Sara Watson c Copyright by Anna M. Meyerrose 2019 Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, international organizations (IOs) have engaged in unprecedented levels of democracy promotion and are widely viewed as positive forces for democracy. However, this increased emphasis on democracy has more re- cently been accompanied by rampant illiberalism and a sharp rise in cases of demo- cratic backsliding in new democracies. What explains democratic backsliding in an age of unparalleled international support for democracy? Democratic backsliding oc- curs when elected officials weaken or erode democratic institutions and results in an illiberal or diminished form of democracy, rather than autocracy. This dissertation argues that IOs commonly associated with democracy promotion can support tran- sitions to democracy but unintentionally make democratic backsliding more likely in new democracies. Specifically, I identify three interrelated mechanisms linking IOs to democratic backsliding. These organizations neglect to support democratic insti- tutions other than executives and elections; they increase relative executive power; and they limit states’ domestic policy options via requirements for membership. Lim- ited policy options stunt the development of representative institutions and make it more difficult for leaders to govern. Unable to appeal to voters based on records of effective governance or policy alternatives, executives manipulate weak institutions to maintain power, thus increasing the likelihood of backsliding. -

Class 1: Reading and Discussion Questions *How Can You Use The

Class 1: Reading and Discussion Questions *How can you use the pieces of the Communist Manifesto represented in the film Manifestoon to better understand the pieces you read for today? *Based on what you've read and what you've just heard about his life and influence, why do you think Marx became such a polarizing figure? What does Lenin identify as the component parts of Marxism? How are they related to each other? Have you heard of these ideas before? If so, what do you know about them? Given the different struggles in which W.E.B. DuBois, Leila Khaled, Ho Chi Minh, and Albert Einstein engaged what common elements brought them to Marx's ideas? What was different for each? According to Einstein, why is it difficult for people to make good use of their political rights under capitalism? How does Einstein characterize a socialist economy? Why does he favor it? What social benefits does he see attached to a socialist economic system? Discuss this statement from DuBois: "Capitalism cannot reform itself; it is doomed to self- destruction. No universal selfishness can bring social good to all." The four readings show how four very different people have been influenced by Marxism: the foremost scientist of the 20th century, an incredibly influential Black theorist of the US, the leader of the Vietnamese revolution, and a dedicated militant in the Palestinian struggle. 1. In Einstein's article, why does he say a planned economy is not yet socialism? 2. What was the most important issue for Ho Chi Minh when he was becoming a socialist and why? 3. -

Globalization and National Development

Globalization and National Development The Perspective of the Chinese Revolution A RIF D IRLIK University of Oregon globalization: the problem of national development under the regime of globalization. The juxtaposition of the terms globalization and national development points to a deep contradiction in contemporary thinking, or a nostalgic longing for an aspiration that may no longer be relevant, but is powerful enough still to disturb the very forces at work in relegating it to the past. There is a suggestion in arguments for globalization that national devel- opment may be achieved through globalization, which in turn would be expected to contribute to further globalization, and so on and so forth into the future, which goes against the tendency of these same arguments to set the global against the national as a negation of the latter. While it may not be a zero-sum relationship, the relationship between globalization and national development is nevertheless a highly disturbed one. Understood as the persistence of commitments to autonomy and sovereignty, most impor- tantly in the realm of the economy, the national obstructs globalization just as globalization erodes the national, at the same time rendering irrelevant ● 241 242 ● Globalization and National Development any idea of development that takes such autonomy and sovereignty as its premise. If we are to take globalization seriously, in other words, the very idea of national development becomes meaningless. On the other hand, if national development as an idea is to be taken seriously, as it was for most of the past century, then globalization appears as little more than an ideo- logical assault on the national, to rid the present of the legacies of that past. -

Mao's War on Women

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2019 Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 Al D. Roberts Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Al D., "Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976" (2019). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7530. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAO’S WAR ON WOMEN: THE PERPETUATION OF GENDER HIERARCHIES THROUGH YIN-YANG COSMOLOGY IN THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PROPAGANDA OF THE MAO ERA, 1949-1976 by Al D. Roberts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Clayton Brown, Ph.D. Julia Gossard, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Li Guo, Ph.D. Dominic Sur, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________________________ Richard S. Inouye, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2019 ii Copyright © Al D. Roberts 2019 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 by Al D. -

THE PEASANTS AS a REVOLUTIONARY CLASS: an Early Latin American View

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Government and International Affairs Faculty Government and International Affairs Publications 5-1-1978 The eP asants as a Revolutionary Class: An Early Latin American View Harry E. Vanden University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gia_facpub Part of the Government Contracts Commons, and the International Relations Commons Scholar Commons Citation Vanden, Harry E., "The eP asants as a Revolutionary Class: An Early Latin American View" (1978). Government and International Affairs Faculty Publications. 93. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gia_facpub/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Government and International Affairs at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government and International Affairs Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARRY E. VANDEN Department of Political Science University of South Florida Tampa, Florida 33620 THE PEASANTS AS A REVOLUTIONARY CLASS: An Early Latin American View We do not regard Marx's theory as something completed and inviolable; on the contrary, we are convinced that it has only laid the foundation stone of the science which socialists must develop in all directions if they wish to keep pace with life. V. I. Lenin (Our Program) The peasant is one of the least understood and most abused actors on the modern political stage. He is maligned for his political passivity and distrust of national political movements. Yet, most of the great twentieth-century revolutions in the Third World have, according to most scholars, been peasant based (Landsberger, 1973: ix; Wolf, 1969). -

SOCIALISM CANNOT BE BUILT in ALLIANCE with the BOURGEOISIE the Experience of the Revolutions in Albania and China Jim Washington, About 1980, USA

SOCIALISM CANNOT BE BUILT IN ALLIANCE WITH THE BOURGEOISIE The Experience of the Revolutions in Albania and China Jim Washington, about 1980, USA CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION 1 I CHINA 4 1 “New Democracy” 4 2 Four Classes in Power 6 3 Gradual and Peaceful Transition to Socialism 7 4 Liu Shao-chi and the Right Wing of the CPC 10 5 The Transformation of Industry and Commerce 13 6 The Eighth Congress of the CPC 15 7 The Decentralization of the Economy and the Wage Reform of 1956 18 8 The “Rectification” of the Party 21 9 “Contradictions Among the People” 23 II ALBANIA 26 1 The Democratic Revolution 26 2 Conciliation With or Expropriation and Suppression of the Bourgeoisie? 27 3 The Struggle Against the Titoite Revisionists 29 4 The Consolidation of Socialist Relations of Production 30 5 The Struggle Against the Soviet Revisionists 34 III THE PLA’S CRITIQUE OF “NEW DEMOCRACY” IS CORRECT 38 1 The Popularization of the Theory of “New Democracy” 38 2 Alliances with Sectors of the Bourgeoisie in National-Democratic Revolutions 39 3 The Nature of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat and the Class Struggle During 42 the Transition to Socialism IV INTRODUCTION TO PART TWO: CLASS STRUGGLE IN SOCIALIST 50 SOCIETY V LEARNING FROM THE CHINESE AND ALBANIAN EXPERIENCES 56 NOTES 58 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 INTRODUCTION The seizure of power in China by the Teng Hsiao-ping revisionist clique stunned the com- munist movement in our country. Some organizations displayed their opportunism and hastened to consolidate themselves around the increasingly open reactionary line of the Chinese Com- munist Party. -

Prisoners of Conscience AI Index

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Peru: Prisoners of Conscience AI Index: AMR 46/09/96 Distr: SC/CC/CO/PG INTERNATIONAL SECRETARIAT, 1 Easton Street, London, WC1X 8DJ, UK 2 “The control mechanisms established by the [....] anti-terrorism law do not work well. The filters are calibrated to catch both camel and mosquito. Crimes are so ill-defined that anyone could be accused of anything by anybody, and be convicted by them.” “The President ... assured [us] that cases that revealed ‘compelling evidence of innocence’ would be reviewed. Let’s not be mean about it; this is encouraging.” Hubert Lanssiers i, Los Dientes del Dragón, December 1995 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1.THE ANTI-TERRORISM LAWS AND PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE 2.“WITH A HUMAN FACE” - 10 ILLUSTRATIVE CASES OF PERUVIAN PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE 3.SHINING PATH, THE MRTA AND HUMAN RIGHTS 4.RECOMMENDATIONS APPENDIX 1Features of the anti-terrorism laws and unfair trials APPENDIX 2International standards for the protection of human rights, including aspects of the right to a fair trial APPENDIX 3Amnesty International’s reports on human rights violations in Peru published since 1993 THE NAMES: 122 INDIVIDUALS ADOPTED AS “PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE” BY AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL ENDNOTES 4 INTRODUCTION In its annual report on the human rights situation in Peru, published at the “... there have been trials and convictions beginning of 1996, the National [for crimes of terrorism] on the basis of Coordinating Committee for Human Rights uncorroborated or frankly fraudulent (CNDDHH) states that between May 1992 information...”ii and December 1995 “the groups linked to the CNDDHH have taken on 1,390 cases of - Ministry of Justice, July 1995 people unjustly implicated in crimes of terrorism and treason. -

Chinese Foreign Policy During the Maoist Era and Its Lessons for Today

Chinese Foreign Policy during the Maoist Era and its Lessons for Today by the MLM Revolutionary Study Group in the U.S. (January 2007) “U.S. Imperialism Get Out of Asia, Africa and Latin America!” 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 3 A. The Chinese Revolution and its Internationalist Practice— p. 5 Korea and Vietnam B. The Development of Neocolonialism and the Bandung Period p. 7 C. Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party Launch the p. 11 Struggle against Soviet Revisionism D. Maoist Revolutionaries Break with Soviet Revisionism-- p. 15 India, the Philippines, Turkey, Nepal, Latin America and the U.S. E. Support for National Liberation Movements in Asia, Africa p. 21 and the Middle East in the 1960s F. Chinese Foreign Policy in the 1970s p. 27 G. The Response of the New Communist Movement in the U.S. p. 35 H. Some Lessons for Today p. 37 2 Introduction Our starting point is that the struggle for socialism and communism are part of a worldwide revolutionary process that develops in an uneven manner. Revolutions are fought and new socialist states are established country by country. These states must defend themselves; socialist countries have had to devote significant resources to defending themselves from political isolation, economic strangulation and military attack. And they must stay on the socialist road by reinvigorating the revolutionary process and unleashing the political initiative of the masses of working people in all areas of society.1 However, socialist countries cannot be seen as ends in and of themselves. They are not secure as long as imperialism and capitalism exist anywhere in the world. -

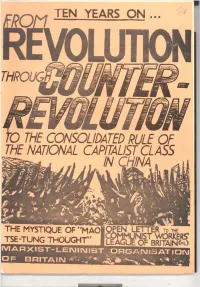

The Consolidated Rule of the National Capitalist Class in ~Na

TEN YEARS ON ... · THE CONSOLIDATED RULE OF THE NATIONAL CAPITALIST CLASS IN ~NA THE MYSTIQUE OF ''MAO _ __... TSE -TUNG THOUGHT'' I N T R 0 D U C T I 0 N THE HISTORY OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA SINCE 1966 HAS FULLY VINDICATED THE MLOBiS EXPOSuRE OF .THE COUNTER-REVOLUTIO~ARY "GREAT PROLETARIAN CULTURAL REVOLUTION" It is now almost 10 years since the Marxist-Leninist Organisation of Britain issued its historic "Report on the Situation in the People's Republic of China". This now classic analysis of the origins L s!e.yelopment and alignment of class forces in the "Great -Proletarian Cultural Revolution" of 1966-68 showed tha.b behind the demagogic mask of "socialism" in China lay: a tacTica_]J.y con:c;aled~apparatus of p ower through which- the chineE_e national- capitalist class could make its dictator ship effective in the specific conditions of a Chine. the workers and peasants of which had carried through, 17 years earlier ~ -a victu~ious national-democratic revol ution and whose revolutionary zeal and striving for fundamental social change remained at a high level. The objective situation ~n the newly-founded People's Republic of China in which, in the years immediately following the victory of the national-democratic revolution in 1949, the national capitalist class found itself, in which it was compelled to lay the first foundations of its economic system and to mould and strengthen its state apparatus of rule - the two together, base and superstructure, making up the system of "new democracy", the blueprint-for which was