The Amount of Solute That Dissolves Can Vary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time Did you know? According to the CDC, contaminated equipment is one of the top five risk factors that contribute to foodborne illnesses. Food contact surfaces in your establishment must be cleaned and sanitized. This can be done either by heating an object to a high enough temperature to kill harmful micro-organisms or it can be treated with a chemical sanitizing compound. 1. Heat Sanitization: Allowing a food contact surface to be exposed to high heat for a designated period of time will sanitize the surface. An acceptable method of hot water sanitizing is by utilizing the three compartment sink. The final step of the wash, rinse, and sanitizing procedure is immersion of the object in water with a temperature of at least 170°F for no less than 30 seconds. The most common method of hot water sanitizing takes place in the final rinse cycle of dishwashing machines. Water temperature must be at least 180°F, but not greater than 200°F. At temperatures greater than 200°F, water vaporizes into steam before sanitization can occur. It is important to note that the surface temperature of the object being sanitized must be at 160°F for a long enough time to kill the bacteria. 2. Chemical Sanitization: Sanitizing is also achieved through the use of chemical compounds capable of destroying disease causing bacteria. Common sanitizers are chlorine (bleach), iodine, and quaternary ammonium. Chemical sanitizers have found widespread acceptance in the food service industry. These compounds are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and consequently require labeling with the word “Sanitizer.” The labeling should also include what concentration to use, data on minimum effective uses and warnings of possible health hazards. -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

101 Lime Solvent

Sure Klean® CLEANING & PROTECTIVE TREATMENTS 101 Lime Solvent Sure Klean® 101 Lime Solvent is a concentrated acidic cleaner for dark-colored brick and tile REGULATORY COMPLIANCE surfaces which are not subject to metallic oxidation. VOC Compliance Safely removes excess mortar and construction dirt. Sure Klean® 101 Lime Solvent is compliant with all national, state and district VOC regulations. ADVANTAGES • Removes construction dirt and excess mortar with TYPICAL TECHNICAL DATA simple cold water rinse. Clear, brown liquid • Removes efflorescence from new brick and new FORM Pungent odor stone construction. SPECIFIC GRAVITY 1.12 • Safer than muriatic acid on colored mortar and dark-colored new masonry surfaces. pH 0.50 @ 1:6 dilution • Proven effective since 1954. WT/GAL 9.39 lbs Limitations ACTIVE CONTENT not applicable • Not generally effective in removal of atmospheric TOTAL SOLIDS not applicable stains and black carbon found on older masonry VOC CONTENT not applicable surfaces. Use the appropriate Sure Klean® FLASH POINT not applicable restoration cleaner to remove atmospheric staining from older masonry surfaces. FREEZE POINT <–22° F (<–30° C) • Not for use on polished natural stone. SHELF LIFE 3 years in tightly sealed, • Not for use on treated low-E glass; acrylic and unopened container polycarbonate sheet glazing; and glazing with surface-applied reflective, metallic or other synthetic coatings and films. SAFETY INFORMATION Always read full label and SDS for precautionary instructions before use. Use appropriate safety equipment and job site controls during application and handling. 24-Hour Emergency Information: INFOTRAC at 800-535-5053 Product Data Sheet • Page 1 of 4 • Item #10010 – 102715 • ©2015 PROSOCO, Inc. -

Carbon Monoxide Levels and Risks

Carbon Monoxide Levels and Risks CO Level Action CO Level Action 0.1 ppm Natural atmosphere level or clean air. 70-75 ppm Heart patients experience an increase in chest pain. Significant decrease in 1 ppm An increase of 1 ppm in the maximum dai- oxygen available to the myocardium/ ly one-hour exposure is associated with a heart (HbCO 10%). 0.96 percent increase in the risk of hospi- 100 ppm Headache, tiredness, dizziness, nausea talization from cardiovascular disease within 2 hrs of exposure. At 5 hrs, dam- among people over the age of 65. age to hearts and brains. (Lewey & Drabkin) (Circulation: Journal of the AHA, Sept, 2009) 200 ppm Healthy adults will have headache, nau- 3-7 ppm 6% increase in the rate of admission in sea at this level. hospitals of non-elderly for asthma. (L. Shep- pard et al.,Epidemiology, Jan 1999) NIOSH & OSHA recommend evacua- tion of the workplace at this level. 5-6 ppm Significant risk of low birth weight if exposed during last trimester - in a study 400 ppm Frontal headache within 1-2 hours—life of 125,573 pregnancies (Ritz & Yu, Environ. threatening within 3 hours. Health Perspectives, 1999). 500 ppm Concentration in a garage when a cold 9 ppm EPA and WHO maximum outdoor air lev- car is started in an open garage and el, all ages, (TWA, 8 hrs). Maximum allow- warmed up for 2 minutes. (Greiner, 1997) able indoor level (ASHRAE) 800 ppm Healthy adults will have nausea, dizzi- Lowest CO level producing significant ef- ness and convulsions within 45 fects on cardiac function (ST-segment minutes. -

Solvent Effects on the Thermodynamic Functions of Dissociation of Anilines and Phenols

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1982 Solvent effects on the thermodynamic functions of dissociation of anilines and phenols Barkat A. Khawaja University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Khawaja, Barkat A., Solvent effects on the thermodynamic functions of dissociation of anilines and phenols, Master of Science thesis, Department of Chemistry, University of Wollongong, 1982. -

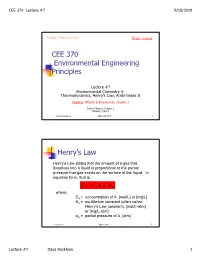

CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Henry's

CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Updated: 18 September 2019 Print version CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Lecture #7 Environmental Chemistry V: Thermodynamics, Henry’s Law, Acids-bases II Reading: Mihelcic & Zimmerman, Chapter 3 Davis & Masten, Chapter 2 Mihelcic, Chapt 3 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 1 Henry’s Law Henry's Law states that the amount of a gas that dissolves into a liquid is proportional to the partial pressure that gas exerts on the surface of the liquid. In equation form, that is: C AH = K p A where, CA = concentration of A, [mol/L] or [mg/L] KH = equilibrium constant (often called Henry's Law constant), [mol/L-atm] or [mg/L-atm] pA = partial pressure of A, [atm] David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 2 Lecture #7 Dave Reckhow 1 CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Henry’s Law Constants Reaction Name Kh, mol/L-atm pKh = -log Kh -2 CO2(g) _ CO2(aq) Carbon 3.41 x 10 1.47 dioxide NH3(g) _ NH3(aq) Ammonia 57.6 -1.76 -1 H2S(g) _ H2S(aq) Hydrogen 1.02 x 10 0.99 sulfide -3 CH4(g) _ CH4(aq) Methane 1.50 x 10 2.82 -3 O2(g) _ O2(aq) Oxygen 1.26 x 10 2.90 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 3 Example: Solubility of O2 in Water Background Although the atmosphere we breathe is comprised of approximately 20.9 percent oxygen, oxygen is only slightly soluble in water. In addition, the solubility decreases as the temperature increases. -

Pressure Vs. Volume and Boyle's

Pressure vs. Volume and Boyle’s Law SCIENTIFIC Boyle’s Law Introduction In 1642 Evangelista Torricelli, who had worked as an assistant to Galileo, conducted a famous experiment demonstrating that the weight of air would support a column of mercury about 30 inches high in an inverted tube. Torricelli’s experiment provided the first measurement of the invisible pressure of air. Robert Boyle, a “skeptical chemist” working in England, was inspired by Torricelli’s experiment to measure the pressure of air when it was compressed or expanded. The results of Boyle’s experiments were published in 1662 and became essentially the first gas law—a mathematical equation describing the relationship between the volume and pressure of air. What is Boyle’s law and how can it be demonstrated? Concepts • Gas properties • Pressure • Boyle’s law • Kinetic-molecular theory Background Open end Robert Boyle built a simple apparatus to measure the relationship between the pressure and volume of air. The apparatus ∆h ∆h = 29.9 in. Hg consisted of a J-shaped glass tube that was Sealed end 1 sealed at one end and open to the atmosphere V2 = /2V1 Trapped air (V1) at the other end. A sample of air was trapped in the sealed end by pouring mercury into Mercury the tube (see Figure 1). In the beginning of (Hg) the experiment, the height of the mercury Figure 1. Figure 2. column was equal in the two sides of the tube. The pressure of the air trapped in the sealed end was equal to that of the surrounding air and equivalent to 29.9 inches (760 mm) of mercury. -

Solvent-Tunable Binding of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Guests by Amphiphilic Molecular Baskets Yan Zhao Iowa State University, [email protected]

Chemistry Publications Chemistry 8-2005 Solvent-Tunable Binding of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Guests by Amphiphilic Molecular Baskets Yan Zhao Iowa State University, [email protected] Eui-Hyun Ryu Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/chem_pubs Part of the Chemistry Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ chem_pubs/197. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemistry at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chemistry Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Solvent-Tunable Binding of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Guests by Amphiphilic Molecular Baskets Abstract Responsive amphiphilic molecular baskets were obtained by attaching four facially amphiphilic cholate groups to a tetraaminocalixarene scaffold. Their binding properties can be switched by solvent changes. In nonpolar solvents, the molecules utilize the hydrophilic faces of the cholates to bind hydrophilic molecules such as glucose derivatives. In polar solvents, the molecules employ the hydrophobic faces of the cholates to bind hydrophobic guests. A water-soluble basket can bind polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons including anthracene, pyrene, and perylene. The binding free energy (−ΔG) ranges from 5 to 8 kcal/mol and is directly proportional to the surface area of the aromatic hosts. Binding of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic guests is driven by solvophobic interactions. Disciplines Chemistry Comments Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Journal of Organic Chemistry 70 (2005): 7585, doi:10.1021/ jo051127f. -

I. the Nature of Solutions

Solutions The Nature of Solutions Definitions Solution - homogeneous mixture Solute - substance being dissolved Solvent - present in greater amount Types of Solutions SOLUTE – the part of a Solute Solvent Example solution that is being dissolved (usually the solid solid ? lesser amount) solid liquid ? SOLVENT – the part of a solution that gas solid ? dissolves the solute (usually the greater liquid liquid ? amount) gas liquid ? Solute + Solvent = Solution gas gas ? Is it a Solution? Homogeneous Mixture (Solution) Tyndall no Effect? Solution Is it a Solution? Solution • homogeneous • very small particles • no Tyndall effect • particles don’t settle • Ex: •rubbing alcohol Is it a Solution? Homogeneous Mixture (Solution) Tyndall no Effect? yes Solution Suspension, Colloid, or Emulsion Will mixture separate if allowed to stand? no Colloid (very fine solid in liquid) Is it a Solution? Colloid • homogeneous • very fine particles • Tyndall effect • particles don’t settle • Ex: •milk Is it a Solution? Homogeneous Mixture (Solution) Tyndall Effect? no yes Solution Suspension, Colloid, or Emulsion Will mixture separate if allowed to stand? no yes Colloid Suspension or Emulsion Solid or liquid particles? solid Suspension (course solid in liquid) Is it a Solution? Suspension • homogeneous • large particles • Tyndall effect • particles settle if given enough time • Ex: • Pepto-Bismol • Fresh-squeezed lemonade Is it a Solution? Homogeneous Mixture (Solution) Tyndall no Effect? yes Solution Suspension, Colloid, or Emulsion Will mixture separate if allowed to stand? no yes Colloid Suspension or Emulsion Solid or liquid particles? solid liquid Suspension (course solid in liquid) Emulsion (liquid in liquid) Is it a Solution? Emulsion • homogeneous • mixture of two immiscible liquids • Tyndall effect • particles settle if given enough time • Ex: • Mayonnaise Pure Substances vs. -

Chapter 18 Solutions and Their Behavior

Chapter 18 Solutions and Their Behavior 18.1 Properties of Solutions Lesson Objectives The student will: • define a solution. • describe the composition of solutions. • define the terms solute and solvent. • identify the solute and solvent in a solution. • describe the different types of solutions and give examples of each type. • define colloids and suspensions. • explain the differences among solutions, colloids, and suspensions. • list some common examples of colloids. Vocabulary • colloid • solute • solution • solvent • suspension • Tyndall effect Introduction In this chapter, we begin our study of solution chemistry. We all might think that we know what a solution is, listing a drink like tea or soda as an example of a solution. What you might not have realized, however, is that the air or alloys such as brass are all classified as solutions. Why are these classified as solutions? Why wouldn’t milk be classified as a true solution? To answer these questions, we have to learn some specific properties of solutions. Let’s begin with the definition of a solution and look at some of the different types of solutions. www.ck12.org 394 E-Book Page 402 Homogeneous Mixtures A solution is a homogeneous mixture of substances (the prefix “homo-” means “same”), meaning that the properties are the same throughout the solution. Take, for example, the vinegar that is used in cooking. Vinegar is approximately 5% acetic acid in water. This means that every teaspoon of vinegar contains 5% acetic acid and 95% water. When a solution is said to have uniform properties, the definition is referring to properties at the particle level. -

Worksheet 6 Solutions MATH 1A Fall 2015

Worksheet 6 Solutions MATH 1A Fall 2015 for 27 October 2015 These problems are taken from a set of science problems for calculus written by Jim Belk, avail- able at math.bard.edu/belk/writing.htm. If you’re looking for more practice on related rates or exponential growth, check it out! His problems are less terminally boring than the textbook’s problems. Exercise 6.1. In chemistry and physics, Boyle’s Law describes the relationship between the pressure and volume of a fixed quantity of gas maintained at a constant temperature. The law states that: PV = a constant where P is the pressure of the gas, and V is the volume. dP dV 1. Take the derivative of Boyle’s law to find an equation relating , , P, and V. dt dt 2. A sample of gas is placed in a cylindrical piston. At the beginning of the experiment, the gas occupies a volume of 250 cm3, and has a pressure of 100 kPa. The piston is slowly compressed, decreasing the volume of the gas at a rate of 50 cm3/min. How quickly will the pressure of the gas initially increase? Solution. For the first question, by taking an implicit derivative (using the product rule on the left hand side) we find dP dV V + P = 0. dt dt For the second question, we simply plug the values provided into the equation we’ve just found, dP (250) + (100)(50) = 0, dt dP and solve to find dt = 20 kPa/min. Exercise 6.2. In chemistry, the pH of a solution is defined by the formula pH = −0.4343 ln(a), where a is the hydrogen ion activity (a measure of the “effective concentration” of hydrogen ions). -

Influence of Hydrophobe Fraction Content on the Rheological Properties of Hydrosoluble Associative Polymers Obtained by Micellar Polymerization

http://www.e-polymers.org e-Polymers 2012, no. 009 ISSN 1618-7229 Influence of hydrophobe fraction content on the rheological properties of hydrosoluble associative polymers obtained by micellar polymerization Enrique J. Jiménez-Regalado,1* Elva B. Hernández-Flores2 1Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (CIQA) Blvd. Enrique Reyna #140, 25253, Saltillo, Coahuila, México; e-mail: [email protected] bCentro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (CIQA) Blvd. Enrique Reyna #140, 25253, Saltillo, Coahuila, México; e-mail: [email protected] (Received: 20 November, 2009; published: 22 January, 2012) Abstract: The synthesis, characterization and rheological properties in aqueous solutions of water-soluble associative polymers (AP’s) are reported. Polymer chains consisting of water-soluble polyacrylamides, hydrophobically modified with low amounts of N,N-dihexylacrylamide (1, 2, 3 and 4 mol%) were prepared via free radical micellar polymerization. The properties of these polymers, with respect to the concentration of hydrophobic groups, using steady-flow and oscillatory experiments were compared. An increase of relaxation time (TR) and modulus plateau (G0) was observed in all samples studied. Two different regimes can be clearly distinguished: a first unentangled regime where the viscosity increase rate strongly depends on hydrophobic content and a second entangled regime where the viscosity follows a scaling behavior of the polymer concentration with an exponent close to 4. Introduction Water-soluble polymers are of great interest from the scientific as well as the technological point of view. These polymers have been subjected to extensive research [1]. Water-soluble polymers are present in the composition of different types of industrial formulations as stabilizing, flocculants, absorbent, emulsifiers, thickeners, etc.