Full Text-PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

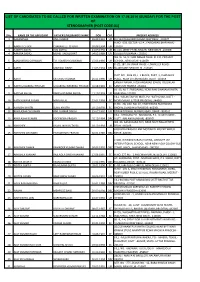

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

Sub-Centre Status of Balangir District

SUB-CENTRE STATUS OF BALANGIR DISTRICT Sl No. Name of the Block Name of the CHC Name of Sector Name of PHC(N) Sl No. Name of Subcenter 1 Agalpur 1 Agalpur MC 2 2 Babupali 3 3 Nagaon 4 4 Rengali 5 5 Rinbachan 6 Salebhata Salebhata PHC(N) 6 Badtika 7 7 Bakti CHC 8 AGALPUR 8 Bendra Agalpur 9 9 Salebhata 10 10 Kutasingha 11 Roth Roth PHC(N) 11 Bharsuja 12 Dudka PHC(N) 12 Duduka 13 13 Jharnipali 14 14 Roth 15 15 Uparbahal 1 Sindhekela 16 Alanda 2 Sindhekela 17 Arsatula 3 Sindhekela 18 Sindhekela MC 4 Sindhekela 19 Dedgaon 5 Bangomunda Bangomunda PHC(N) 20 Bangomunda 6 Bangomunda Bhalumunda PHC(N) 21 Bhalumunda 7 Bangomunda Belpara PHC(N) 22 Khaira CHC 8 BANGOMUNDA Bangomunda 23 Khujenbahal Sindhekela 9 Chandotora 24 Batharla 10 Chandotora 25 Bhuslad 11 Chandotora 26 Chandutara 12 Chandotora 27 Tureikela 13 Chulifunka 28 Biripali 14 Chulifunka Chuliphunka PHC(N) 29 Chuliphunka 15 Chulifunka 30 Jharial 16 Chulifunka 31 Munda padar 1 Gambhari 32 Bagdor 2 Gambhari 33 Ghagurli 3 Gambhari Gambhari OH 34 Ghambhari 4 Gambhari 35 Kandhenjhula 5 Belpada 36 Belpara MC 6 Belpada 37 Dunguripali 7 Belpada 38 Kapani 8 Belpada 39 Nunhad 9 Mandal 40 Khairmal CHC 10 BELPARA Mandal Khalipathar PHC(N) 41 Khalipatar Belpara 11 Mandal 42 Madhyapur 12 Mandal Mandal PHC(N) 43 Mandal 13 Mandal 44 Dhumabhata 14 Mandal Sulekela PHC(N) 45 Sulekela 15 Salandi 46 Bahabal 16 Salandi 47 Banmal 17 Salandi 48 Salandi 18 Salandi 49 Sarmuhan 19 Salandi 50 Kanut 1 Chudapali 51 Barapudugia 2 Chudapali Bhundimuhan PHC(N) 52 Bhundimuhan 3 Chudapali 53 Chudapali MC 4 Chudapali 54 -

Title of the Project:” Risk Reduction and Livelihood Promotion in Western Orissa”: a Consortium Initiative

Title of the Project:” Risk Reduction and Livelihood Promotion in Western Orissa”: A Consortium Initiative estern Orissa is the home to W situation of more chronically food insecurity than any other region in the state of Orissa. Visiting of droughts and flash floods are recurrent and common phenomena in Western Orissa. It is estimated that around two- third of the total population in this region face the problems of food insecurity for around nine months, as a result migration to towns and cities in search of livelihood is rampant. During the current decade in the year 2002 this area visited severe drought making the situation of people vulnerable. 81° 82° 83° 84° 85° 86° 87° 88° N ORISSA JHARKHAND W E District Wise Rain Fall Trend S DROUGHT HISTORY In Western Orissa WEST BENGAL July - 2002 22° 22° Sundargarh 1950-60 Twice Jharsuguda Mayurbhanj Keonjhar Deogarh 1960-70 Twice Balasore Baragarh Sambalpur CHHATISH GARH 21° 21° Bhadrak 1970-80 Five times Sonepur Angul Dhenkanal Jajpur Boudh Kendrapara Cuttack 1980-90 Six times Bolangir Jagatsinghpur Nuapada Khurda Nayagarh 20° 1990-2001 Thrice 20° Phulbani Puri l a g Kalahandi n 2002-2003 Statewide e Ganjam B Nawarangpur Rayagada 19° f o Drought 19° Gajapati Koraput y Reference a Rain Fall ANDHRA PRADESH Rain Fall Normal B Scanty (-60% and above) Malkangiri Rain Fall Actual Highly Deficient (-40% to -59%) National Boundary 18° 18° Deficient (-20% to -39% ) State Boundary Normal (+19% to -19%) District Boundary Composed and Printed at SPARC Pvt. ltd., Bhubaneswar Continuous erratic rainfall, undulated terrain, 81° 82° 83° 84° 85° 86° 87° 88° fragmented ecology followed by frequent droughts has severely affected the economic condition of the poor in Orissa, especially in the districts of Western Orissa since last few decades. -

Sustainable Livelihood Development of Migrant Families Through Relief and Rehabilation Programme Affacted by Covid 19 in Kalhaandi and Nuapada District of Odisha”

1. NAME OF THE PROJECT: “SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOOD DEVELOPMENT OF MIGRANT FAMILIES THROUGH RELIEF AND REHABILATION PROGRAMME AFFACTED BY COVID 19 IN KALHAANDI AND NUAPADA DISTRICT OF ODISHA” 2.1. Organizational information (A) Name of the Organisation : KARMI (KALAHANDI ORGANISATION FOR AGRICULTURE AND RURAL MARKETING INITIATIVE) (B) Address AT/PO. – MAHALING (KADOBHATA) VIA. – BORDA, PIN - 766 036, ODISHA, INDIA E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 9777779248, 7978958677 (C) Contact Person Mr. Abhimanyu Rana Secretary, KARM (D) Legal Status i) Registered under Society Registration Act - XXI,1860 Regd.No.-KLD-2091/444- 1996-97, Dt. 28th Jan. 1997 ii) Regd. Under FCRA 1976, by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India Regd. No. 104970037, Dt. 19th Nov. 1999 iii) Registered under Income Tax Act. 12A of 1961 Regd. No. - Judl/12A/99-2000/14326, Dt. 14th Feb. 2000 iv) Registered under Income Tax Act. 80G of 1961 Regd.No- CIT/SBP/Tech/80 G/2012-13/1849 Dt.16/07/2012 v). PAN No - AAATK4333L (E) Bank Particulars General - Ac/ No. - 118583 43699 FCRA A/C NO- 118583 43076 STATE BANK OF INDIA, CHANDOTARA BRANCH (Code - 8880) AT/PO - CHANDOTARA, PIN - 767 035 VIA - SINDHEKELA, DIST. – BALANGIR., ODISHA, INDIA Bank Branch Code – 8880 IFSC Code – SBIN0008880 MICR Code-767002014 Bank Swift Code- SBININBB270 (F) Area of Operation Sl. Project District Block G.P Village Population Total No ST SC OC 1 Golamunda Kalahandi Golamunda 20 62 13738 6296 18587 38621 2 M.Rampur Kalahandi M.Rampur 12 54 17633 12035 16054 45722 3 Boden Nuapada Boden 15 96 27621 9419 39630 76670 4 Titilagarh Bolangir Titilagarh 6 35 14670 9113 12595 36378 5 Narla Kalahandi Narla 5 20 7365 6050 16997 30412 TOTAL 3 District 5 Block 58 267 81027 42913 103863 227803 2.2. -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

Inspection Note on Revenue Divisional Commissioner,Northern

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA INSPECtION NOtE OF ShRI VIPIN SAXENA, I.A.S. , hON’BLE MEMBER, BOARD OF REVENUE, ODIShA, CUttACK ON thE OFFICE OF thE REVENUE DIVISIONAL COMMISSIONER, NORthERN DIVISION, SAMBALPUR ON 17th NOVEMBER, 2016 I N D E X Sl. Subject. Page No. No. 1. Introduction. 1 2. Accommodation. 1 3. Charge. 2 4. Inspection. 2 5. Tour. 5 6. Court. 5 7. Demand, Collection & Balance. 10 8. Annual Land Revenue Administration Report. 16 9. Irrigation. 17 10. Sairat. 21 11. Certificate Cases. 23 12. Lease Cases. 24 13. Encroachment. 26 14. Government Waste Land. 27 15. Bebandobasta Cases. 29 16. Mutation Cases. 29 17. Land Acquisition. 31 18. Land Reforms. 31 19. Master Plan of Urban Area. 39 20. Establishment. 40 21. Budget & Nizarat. 46 22. Vehicle. 51 23. Misappropriation. 51 24. I.R. & A.R. Report. 52 25. Record Room. 52 26. Library. 56 27. Emergency 57 Inspection Note of Shri Vipin Saxena, I.A.S., Hon’ble Member, Board of Revenue, Odisha, Cuttack on the office of the Revenue Divisional Commissioner, Northern Division, Sambalpur. Date of Inspection : 17th November, 2016. 1. Introduction : The office of the Revenue Divisional Commissioner, Northern Division, Sambalpur started functioning as per Notification No.NBo.10838, dgt.30.08.1957 of Govt. in Political & Services Department, Odisha, Bhubaneswar published in Odisha Gazette Extra-Ordinary issue No.322, dt.30.08.1957 having its Headquarters at SAMBALPUR. This Revenue Division consists of originally five districts namely Sambalpur, Sundargarh, Keonjhar, Balangir and Dhenkanal. But, after new organization of District Administration, these Districts were bifurcated and at present, 10(Ten) Districts as detailed below are under its administrative control. -

Tahasildar JOINT Dirf~~':Dk~OGY '-Tarbha ZONAL SURVEY,BALANGIR

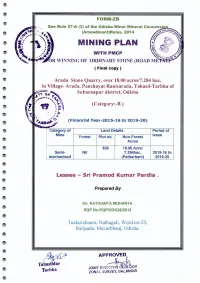

FORM-ZB ( Final copy) Arada Stone Quarry, over 18.00 acres/7.284 hac. in Village- Arada, Panchayat Ranisarada, Tahasil- Tarbha of Subarnapur district, Odisha (Category:-B ) (Financial Year-2015-16 to 2019-20) Category of Land Details Period of Mine f---=F-or-e-st-:---.------=P-=--r---IoN-,-=-=-t-n-o-n. --=Fo-r-e-stlease=----------I Acres 536 18.00 Acrel Semi- Nil 7.284hac. 2015-16 to I mechanised (Patharbani) 2019-20 Lessee - Sri Pramod Kumar Pardia • Prepared By Sri. RATIKANTA MOHANTA RQP No-RQP/OD/026/2015 Tualasichaura, Nathagali, Word.no-23, Baripada, Mayurbhanj, Odisha. ~.Ib APPRnk Tahasildar JOINT DiRf~~':dk~OGY '-Tarbha ZONAL SURVEY,BALANGIR • Chapter Description I Consent Letter from Lessee II Certificate from Lessee III Form- ZB Certificate & Undertaking IV List of Plates V Annexure • • ~~~~ RATIKANTA MOHANTA Reg.No .•RQP/OD/026120t5 • iii • CONSENT LETTER FROM THE APPLICANT The Mining Plan of Arada Stone Quarry of Sri Pramod Kumar Pardia for the period of 2015-16 to 2019-20 over an area of 18.00 Acre/7.284 hac, in village Arada in Subarnapur District has been prepared under provisions of Odisha Minor Mineral Concession Rules(Amendment), 2014 & 2015, by Sri Ratikanta Mohanta, RQP/OD/026/2015 . I request the joint Director Geology, Balangir, Orissa to make further correspondence with the RQP regarding modification/rectification of the mining plan in the following address. Sri RATlKANTA MOHANTA At- Nathagali, Ward No-23, Tulasichaura, Baripada, Mayurbhanj - 757001(Odisha) E [email protected] Mobile - 9437545363 We hereby undertake that the mining plan prepared by the RQPshall be deemed to have been made with our knowledge and consent and shall be acceptable to us and binding on me in all respect. -

Y Report (Dsr) of Balangir District, Odisha

Page | 1 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF BALANGIR DISTRICT, ODISHA. FOR ROAD METAL/BUILDING STONE/BLACK STONE (FOR PLANNING & EXPLOITATION OF MINOR MINERAL RESOURCES) ODISHA BALANGIR As per Notification No. S.O. 3611(E) New Delhi dated 25th July 2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change (MoEF & CC) COLLECTORATE BALANGIR Page | 2 CONTENT CH. DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. NO. Preamble 4-5 1 Introduction 1.1 Location and Geographical Area 6-9 1.2 Administrative Units 9-10 1.3 Connectivity 10-13 2 Overview of Mining Activity in the District 13 3 General Profile of the District 3.1 Demography 14 4 Geology of the District 4.1 Physiography & Geomorphology 15-22 4.2 Soil 22-23 4.3 Mineral Resources. 23-24 5 Drainage of Irrigation Pattern 5.1 River System 25 6 Land Utilization Pattern in the District 6.1 Forest and non forest land. 26-27 6.2 Agricultural land. 27 6.3 Horticultural land. 27 7 Surface Water and Ground Water Scenario of the District 7.1 Hydrogeology. 28 7.2 Depth to water level. 28-30 7.3 Ground Water Quality. 30 7.4 Ground Water Development. 31 7.5 Ground water related issues & problems. 31 7.6 Mass Awareness Campaign on Water Management 31 Training Programme by CGWB 7.7 Area Notified By CGWB/SGWA 31 7.8 Recommendations 32 8 Rainfall of the District and Climate Condition 8.1 Month Wise rainfall. 32-33 8.2 Climate. 33-34 9 Details of Mining Lease in the District 9.1 List of Mines in operation in the District 34 Page | 4 PREAMBLE Balangir is a city and municipality, the headquarters of Balangir district in the state of Odisha, India. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Town and Village Directory, Bolangir, Part-A, Series-16, Orissa

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1971 SERIES 16 ORISSA PART X DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOO~ PART A-TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY BOLANGIR B. TRIPATHI of- the Indian Administrative Service Director Df Census Operations, Orissa CENSUS OF INDIA, 1971 DISTRICT CENSUS HA-NDBOOK PART A-TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY BOLA_NGIR PREFACE The District Census Handbook first introduced.as an ancillary to 1951 Census appeared as a State. Government publication in a more elaborate and ambitious form in 1961 Census. It was divided into 3 parts: Part] gave a narrative account of each District; Part 1I contained various Census Tables and a ~eries of Primary Census data relating to each village and town ; and Part III presented certain administrative statistics obtained from Government Departments. These parts further enriched by inclusion of maps of the district and of police stations within the district were together -brought out in ODe volume. The Handbook, for each one of the 13 Districts of the State was acknowledged to be highly useful. 2. But the purpose and utility of this valuable compilation somewhat suffered on account of the time lag that intervened between the conclusion of Census and the publication of the Handbook. The delay was unavoidable in the sense that the Handbook-complete with all the constituent parts brought together in one volume had necessarily<to wait till after completion of the processing and tabulation of Gensus data and collection and compilation of a large array of administrative and other statistics. 3. With the object of cutting out the delay, and also_ to making each volume handy and not-too-bulky it has been decided to bring out the 1971 District Census Handbook in three parts separately with the data becoming available from stage to stage as briefly indicated below : Part A-This part will incorporate the Town Directory and the Village Directory for each district. -

A Study on School Culture & Physical

A STUDY ON SCHOOL CULTURE & PHYSICAL ACTIVITIES IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS OF BALANGIR DISTRICT PJAEE, 17 (12) (2020) "A STUDY ON SCHOOL CULTURE & PHYSICAL ACTIVITIES IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS OF BALANGIR DISTRICT" MISS MARY KAMOLINA EKKA PH.D SCHOLAR, DR PMIASE SAMBALPUR, ODISHA, INDIA DR NIBEDITA GURU GUIDE, PRINCIPAL, CTE BALANGIR, ODISHA, INDIA Miss Mary Kamolina Ekka , Dr Nibedita Guru, A STUDY ON SCHOOL CULTURE & PHYSICAL ACTIVITIES IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS OF BALANGIR DISTRICT, -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(12). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: School Culture, Physical Activities, Secondary Schools. ABSTRACT I mean the whole creation of the best of childhood, mind and spirit by education. With regard to the concept, I thought that physical education education improves the overall growth of the child's body, mind and spirit. To date, physical and physical education has become a demonstration of a future education society in the 21st century. In this perspective, the researcher conducts the analysis by descriptive study method in 170 high-school students in the Bolangir district and five students and PET instructors of each school. Introduction: According to NASPE, an instructional programme of high quality improves the physical, emotional, and emotions of every child and offers health evaluation to help children recognise, develop and/or preserve their fitness.In other words the all- round development of a child is possible through physical activities. That’s why it is said that - “Sound mind resides in a sound body”. So regular physical activities in schools are an integral part of the students' full and total education curriculum and a way of making a positive effect on health and well-being in their lives.