Method of Legitimization of the Kingdom of Sambalpur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

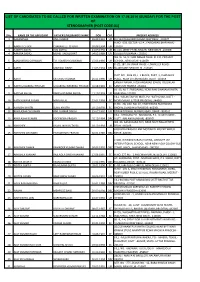

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

E:\Review\Or-2021\Or Feb-March

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Political Evolution in Ex-Princely State of Patna Under the Dynamic Leadership of Maharaja Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo Dr. Suresh Prasad Sarangi Abstract: (The ex-princely State of Patna was ruled by Maharaja Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo from 1931 to 1948. During his tenure as Maharaja, Sri Singh Deo tried to introduce a number of democratic reforms for the smooth working and good governance of Patna State. This article is a modest approach to unravel the dynamic administration unleashed by Maharaja Sri Singh Deo in ex-princely state of Patna during his tenure as Maharaja) Keywords: (Governance, Political identity, Suzerain Powers, Democratic set up, feudatory state) Introduction: Deo and Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo were most The history of Patna State dates back to popular and benevolent ruler of the ex-princely Ramai Deo, the real founder of the state who state of Patna. History always remembers founded the Chauhan dynasty in 1320 A.D. Chauhan dynasty of Patna State for their own approximately. But special identity and heroism. It Ramachandra Mallick could maintain its own special argued that the real state of identity in the history of Patna came into exist in the contemporary era and year 1159 A.D. Prior to the particularly out of twenty-six rule of Ramai Deo, the State feudatory states of Odisha of Patna was ruled by the whose existence was found at eight Mullicks or Pradhan. the time of their merger into the This system came to an end Indian Union. Thus, Patna state when Ramai Deo killed all was one of the premier states the Pradhans and declared of all the princely states in himself as the king of Patna. -

L&T Sambalpur-Rourkela Tollway Limited

July 24, 2020 Revised L&T Sambalpur-Rourkela Tollway Limited: Rating upgraded Summary of rating action Previous Rated Amount Current Rated Amount Instrument* Rating Action (Rs. crore) (Rs. crore) [ICRA]A-(Stable); upgraded Fund based - Term Loans 990.98 964.88 from [ICRA]BBB+(Stable) Total 990.98 964.88 *Instrument details are provided in Annexure-1 Rationale The upgrade of the rating assigned to L&T Sambalpur-Rourkela Tollway Limited (L&T SRTL) takes into account the healthy improvement in toll collections since the commencement of tolling in March 2018 along with regular receipt of operational grant from the Odisha Works Department, Government of Odisha (GoO), and reduction in interest rate which coupled with improved toll collections has resulted in an improvement in its debt coverage indicators. The rating continues to draw comfort from the operational stage of the project, and the attractive location of the project stretch between Sambalpur and Rourkela (two prominent cities in Odisha) connecting various mineral-rich areas in the region with no major alternate route risk, and strong financial flexibility arising from the long tail period (balance concession period post debt repayment) which can be used to refinance the existing debt with longer tenure as well as by virtue of having a strong and experienced parent—L&T Infrastructure Development Project Limited (L&T IDPL, rated [ICRA]AA(Stable)/[ICRA]A1+)—thus imparting financial flexibility to L&T SRTL. ICRA also draws comfort from the presence of structural features such as escrow mechanism, debt service reserve (DSR) in the form of bank guarantee equivalent to around one quarter’s debt servicing obligations, and reserves to be built for major maintenance and bullet payment at the end of the loan tenure. -

List of Shortlisted Candidates

Provisionally shortlisted candidates for Zoom Interview for the position of Staff Nurse under NHM, Assam Date of Roll No. Regd. ID Candidate's Name Permanent Address Interview NHM/SNC/2 C/o-Hemen Sarma, H.No.-11, Vill/Town-Forestgate yubnagar narengi, P.O.- 0001 Abhisikha Devi 27.08.2020 413 Narengi, P.S.-Noonmati, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-Assam, Pin-781026 NHM/SNC/1 C/o-SAHABUDDIN AHMED, H.No.-115, Vill/Town-RAHDHALA, P.O.- 0002 AFTARA BEGUM 27.08.2020 249 TAKUNABORI, P.S.-MIKIRBHETA, Dist.-Morigaon, State-ASSAM, Pin-782104 C/o-SULTAN SALEH AHMED, H.No.-1107, Vill/Town-WARD NO 5, NHM/SNC/1 0003 AKLIMA KHATUN GANDHINAGAR, P.O.-BARPETA, P.S.-BARPETA, Dist.-Barpeta, State- 27.08.2020 195 ASSAM, Pin-781301 C/o-MR ARUP KUMAR HANDIQUE, H.No.-0, Vill/Town-2 NO MORAN NHM/SNC/1 0004 ALEE HANDIQUE GAON, P.O.-MORAN GAON, P.S.-TITABOR, Dist.-Jorhat, State-ASSAM, Pin- 27.08.2020 489 785630 NHM/SNC/2 C/o-Subodh Bhengra, H.No.-Beesakopie central hospital, Vill/Town-Doomdooma, 0005 Alice Bhengra 27.08.2020 364 P.O.-Doomdooma, P.S.-Doomdooma, Dist.-Tinsukia, State-Assam, Pin-786151 NHM/SNC/2 C/o-Aftab Hoque, H.No.-106, Vill/Town-Puranigudam, P.O.-Puranigudam, P.S.- 0006 Alisha hoque 27.08.2020 478 Samaguri, Dist.-Nagaon, State-Assam, Pin-782141 NHM/SNC/1 C/o-Amrit Daimari, H.No.-126, Vill/Town-Miripara, P.O.-Sastrapara, P.S.- 0007 Alongbar Daimari 27.08.2020 679 Harisinga, Dist.-Udalguri, State-Assam, Pin-784510 NHM/SNC/1 C/o-Benedict Indwar, H.No.-117, Vill/Town-Boiragimath, P.O.-Dibrugarh, P.S.- 0008 ALVIN INDWAR 27.08.2020 928 Dibrugarh, Dist.-Dibrugarh, -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

The Rajputs: a Fighting Race

JHR1 JEvSSRAJSINGHJI SEESODIA MLJ^.A.S. GIFT OF HORACE W. CARPENTER THE RAJPUTS: A FIGHTING RACE THEIR IMPERIAL MAJESTIES KING-EMPEROR GEORGE V. AND QUEEN-EMPRESS MARY OF INDIA KHARATA KE SAMRAT SRT PANCHME JARJ AI.4ftF.SH. SARVE BHAUMA KK RAJAHO JKVOH LAKH VARESH. Photographs by IV. &* D, Downey, London, S.W. ITS A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE , RAJPUT. ,RAC^ WARLIKE PAST, ITS EARLY CONNEC^tofe WITH., GREAT BRITAIN, AND ITS GALLANT SERVICES AT THE PRESENT MOMENT AT THE FRONT BY THAKUR SHRI JESSRAJSINGHJI SEESODIA " M.R.A.S. BEAUTIFULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH NUMEROUS COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS A FOREWORD BY GENERAL SIR O'MOORE CREAGH V.C., G.C.B., G.C.S.I. EX-COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF, INDIA LONDON EAST AND WEST, LTD. 3, VICTORIA STREET, S.W. 1915 H.H. RANA SHRI RANJITSINGHJI BAHADUR, OF BARWANI THE RAJA OF BARWANI TO HIS HIGHNESS MAHARANA SHRI RANJITSINGHJI BAHADUR MAHARAJA OF BARWANI AS A TRIBUTE OF RESPECT FOR YOUR HIGHNESS'S MANY ADMIRABLE QUALITIES THIS HUMBLE EFFORT HAS BEEN WITH KIND PERMISSION Dedicates BY YOUR HIGHNESS'S MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT AND CLANSMAN JESSRAJSINGH SEESODIA 440872 FOREWORD THAKUR SHRI JESSRAJ SINGHJI has asked me, as one who has passed most of his life in India, to write a Foreword to this little book to speed it on its way. The object the Thakur Sahib has in writing it is to benefit the fund for the widows and orphans of those Indian soldiers killed in the present war. To this fund he intends to give 50 per cent, of any profits that may accrue from its sale. -

Freedom Movement in Jharsuguda District

Orissa Review Sambalpur was occupied by Bamra, Trilochana Rai of the British in 1817 from the Paharsiriguda, Abdhut Sing of Marathas. In 1827, the Bissikella, Medini Bariha of Freedom Chouhan ruler Maharaja Sai Kharmura, Jagabandhubabu (a died and Rani Mohan Kumari, discharged amala of the Rani), Movement in widow of the Chouhan ruler Biju a discharged Duffadar of was installed on the Gaddi of Sambalpur, Shickru Mohanty Jharsuguda Sambalpur. During her reign, (formerly a Namadar of the Zamindari of Jharsuguda Barkandazee), Balaram Sing, District was created in 1829, which Balbhadra Sing Deo of was assigned to one Ranjeet Lakhanpur and many Gond Sing, a near relation for leaders. Govind Sing could Dr. Byomakesh Tripathy maintenance of his family. muster the support of the total Ranjeet Singh was a son of Siva people and thus the movement Sing, grandson of Haribans for freedom in Sambalpur Singh and great grandson of began in Jharsuguda as a The district of Jharsuguda has Chatra Sai, seventh Chouhan protest against British a special niche in the history and ruler of Sambalpur. Ranjeet highhandedness. Thus before culture of Orissa since early Sing and his successor lived 30 years prior to the first war times. Findings of prehistoric with Rajas of Sambalpur and of Independence of 1857 AD, tools, rock shelters of stone age he was in the hope that he might Govind Sing raised his sword period with earliest rock succeed the Gaddi. When the to drive away the British from engravings in India at British appointed the widow Sambalpur. The resistance Vikramkhol and Ulapgarh, Rani on the throne of movement of Govind Sing could ruins of early temples, sculptural Sambalpur. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Final Rationalized Timing on Sambalpur-Jharsuguda-Sundargarh Route (Down Trip)

FINAL RATIONALIZED TIMING ON SAMBALPUR-JHARSUGUDA-SUNDARGARH ROUTE (DOWN TRIP) SUNDERGARH JHARSUGUDA RENGALI SAMBALPUR Sl No Bus Number Route Slot Type DEP ARR DEP ARR DEP ARR 1 EXPRESS 03:10:00 03:55:00 04:00:00 04:39:00 04:41:00 05:15:00 2 ORDINARY 03:15:00 04:00:00 04:05:00 04:52:00 04:54:00 05:35:00 3 ORDINARY 03:20:00 04:05:00 04:10:00 04:57:00 04:59:00 05:40:00 4 EXPRESS 03:25:00 04:10:00 04:15:00 04:54:00 04:56:00 05:30:00 5 ORDINARY 03:30:00 04:15:00 04:20:00 05:07:00 05:09:00 05:50:00 6 ORDINARY 03:35:00 04:20:00 04:25:00 05:12:00 05:14:00 05:55:00 7 EXPRESS 03:40:00 04:25:00 04:30:00 05:09:00 05:11:00 05:45:00 SAMBALPUR TO JHARSUGUDA 2RT , JHARSUGUDA 8 OR15F2157 TO LAIDA ORDINARY 03:45:00 04:30:00 04:35:00 05:22:00 05:24:00 06:05:00 9 OD15B1933 JHARSGUDA TO SAMBALPUR & BACK 3 R.T. DAILY ORDINARY 03:50:00 04:35:00 04:40:00 05:27:00 05:29:00 06:10:00 10 EXPRESS 03:55:00 04:40:00 04:45:00 05:24:00 05:26:00 06:00:00 JHARSUGUDA TO SAMBALPUR & SAMBALPUR TO BRAJARAJNAGAR VIA JHARSUGUDA & 11 OR23B7777 JHARSUGUDA TO BRJARAJNAGAR ORDINARY 04:00:00 04:45:00 04:50:00 05:37:00 05:39:00 06:20:00 12 OR23F3681 JHARSUGUDA TO SAMBALPUR 3RT DAILY ORDINARY 04:05:00 04:50:00 04:55:00 05:42:00 05:44:00 06:25:00 13 EXPRESS 04:10:00 04:55:00 05:00:00 05:39:00 05:41:00 06:15:00 BRAJARAJNAGAR TO SAMBALPUR VIA 14 OR16A5131 JHARSUGUDA 2RT DAILY ORDINARY 04:15:00 05:00:00 05:05:00 05:52:00 05:54:00 06:35:00 BURKHAMUNDA TO SAMBALPUR VIA. -

Thailand 2015, Preserving Its Unique Versatility

Ipsos Flair Collection Thailand 2015, preserving its unique versatility. GAME CHANGERS Thailand 2015, preserving its unique versatility. Ipsos editions April 2015 © 2015 – Ipsos | 2 Guide Ipsos Flair: Understand to anticipate The world economy and relative weights are changing and our companies are willing to develop their business in increasingly important markets: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philippines, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Vietnam… But these countries are unevenly familiar to international firms and there is the risk to simply project outdated stereotypes, so our customers really need information about: - The country values and mood, at a specific time, - The influence of history, religion and culture, - Their vision of the future, their ambitions and desires, their ideals. - Their relation to consumption and brand image So this is why Ipsos Flair was created in the first place: in order to demonstrate the originality and sharpness of Ipsos, because « Flair » is about instinct and intuition. It is the ability to capture the mood, to perceive the right direction, to know when to act… It is also another way of looking, one that considers survey results as sociological symptoms to understand the real relationship between people and everything around them: brands, ads, media… Ipsos is uniquely positioned around five major specializations: marketing; customer & employee satisfaction; media and advertising; public opinion research; and survey management. 3 | By bringing together these diverse, yet complementary, perspectives, we can explore the many different facets of an individual, be it a consumer, a citizen, a spectator, or an employee. France was the pilot country in 2005, followed by Italy in 2010, then China in 2012. -

Asean Pulse, We Bring to Light the Opportunities Awaiting the Business Sector in the Fast-Growing Economies in South East Asia

Issue 2 / Q2 2013 TRENDS THAT ARE SHAPING SOUTHEAST ASIA EVOLVING OPPORTUNITIES THAILAND HOW DOES YOUR GARDEN GROW? UNDERSTAND WHY THAILAND IS DESCRIBED AS THE GATEWAY TO THE ASEAN BLOC VIETNAM A FISH OUT OF WATER? WHY VIETNAM IS STILL A GOOD IDEA MYANMAR THE TRAIN IS LEAVING THE STATION ARE YOU ON BOARD? © 2013 Ipsos www.ipsosasiapacific.com In the second quarterly edition of Asean Pulse, we bring to light the opportunities awaiting the business sector in the fast-growing economies in South East Asia. Countries in focus include Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar. You will find in this issue specific insights about the economic and social elements of these countries that will play an important role in evaluating your branding or market entry strategies. This issue also provides a narrowed profile of each country’s consumer: their characteristics, culture and traditions, and other important influencers of their purchase behavior. Along with this issue is a separate feature report on Thailand as the next luxury shopping hub. CONTENTS A Country View: THAILAND 3 Reaching the Thai Consumer 8 A Country View: VIETNAM 12 Reaching the Vietnamese Consumer 17 A Country View: MYANMAR 20 FIND OUT MORE 25 © 2013 Ipsos A COUNTRY VIEW THAILAND © 2013 Ipsos THAILAND The right Figure 1: Real GDP Growth in 2012 China 7.8% choice for Philippines 6.6% Thailand 6.4% your ASEAN Indonesia 6.2% Malaysia 5.6% hub? South Korea 2.0% Hong Kong 1.4% Singapore 1.3% Taiwan 1.3% After the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was agreed by political leaders, a number of foreign investors began to look closely at ASEAN and its plans to develop into one of the world’s most important economic blocs.