You're on the Air

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

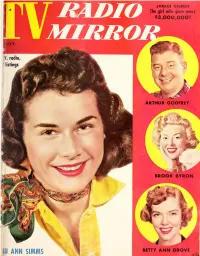

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 16, No. 06

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus mfeii^^jg«;^<^;gs.^gj5«ggg^^ THE NOTRE DAME ALUMNUS /.. ^ "t^ , ^ i -^m-r '^•P\ if.v,VAY ?..- "^n -<-":-i}. i > "l^.*:- -'/f.^^^, Reunion dates: Si? JUNE 3 -m^^?^ «^.%-. 4 ^ 5 ' •> n> (See program inside] f| 174 The Notre Dame Alumnus May. 1938 sirrs The University acknowledges with deep gratitude the following gifts: From Mr. O. L. Rhoades, Siin Manufacturing Company, Chicago. A sun combustion tester, for the Department of Aeronautical Elngincering. From the Studdiafcer Corporation, South Bend. Two bound folio volumes of photostatic copies of dippings referring to the career of the late Knute Rockne. From: The Rev. John O'Brien, Yonkers, N. Y. Mr. Charles F. McTague^ Montdair, N. J. Mr. Edward L. Boyle, Sr., Duluth, Minn. Reference books for special libraries. From the Library of the University of Virginia. Forty-three volumes, for the College of Engineering. For the Rockne Mennorial E. F. Moran. M?: W. B. Moran, 74; J. R. Moran. Rev. J. A. McShane, Winnebago, Mmn. 10 •25: J. A. Moran. 10: and \V. H. Moran, Rev. Michael P. Seter, Evansville, Ind. ._ 10 Tulsa, Oklahoma $1,000 Rev. William Murray, Chicago, Illinois 10 E. T. Fleming, Dallas, Texas 500 Rev. John P. Donahue. Hopedale, Mass. 10 J. A. LaFortune, '18, Tulsa 500 Rev. John C. Vismara, Detroit, Michigan 10 A. \V. Leonard, •89--93. Tulsa 500 Rev. Martin J. Donlon, Brooklyn. N. Y. 10 J. \V. Simmons, Dallas. Texas 250 Rev. -

The Old Time Radio Club Established 1975

The Old Time Radio Club Established 1975 Number 355 December 2007 The fllustrated Pres« Membership Information Club Officers Club Membership: $18.00 per year from January 1 President to December 31. Members receive a tape library list Jerry Collins (716) 683-6199 ing, reference library listing and the monthly 56 Christen Ct. newsletter. Memberships are as follows: If you join Lancaster, NY 14086 January-March, $18.00; April-June, $14; July [email protected] September, $10; October-December, $7. All renewals should be sent in as soon as possible to Vice President & Canadian Branch avoid missing newsletter issues. Please be sure to notify us if you have a change of address. The Old Richard Simpson (905) 892-4688 Time Radio Club meets on the first Monday of the 960 16 Road RR 3 month at 7:30 PM during the months of September Fenwick, Ontario through June at St. Aloysius School Hall, Cleveland Canada, LOS 1CO Drive and Century Road, Cheektowaga, NY. There is no meeting during the month of July, and an Treasurer informal meeting is held in the month of August. Dominic Parisi (716) 884-2004 38 Ardmore PI. Anyone interested in the Golden Age of Radio is Buffalo, I\lY 14213 welcome. The Old Time Radio Club is affiliated with the Old Time Radio Network. Membership Renewals, Change of Address Peter Bellanca (716) 773-2485 Club Mailing Address 1620 Ferry Road Old Time Radio Club Grand Island, NY 14072 56 Christen Ct. [email protected] Lancaster, NY 14086 E-Mail Address Membership Inquires and OTR otrclub(@localnet.com Network Related Items Richard Olday (716) 684-1604 All Submissions are subject to approval 171 Parwood Trail prior to actual publication. -

University Library 11

I ¡Qt>. 565 MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PRINCIPAL PLAY-BY-PLAY ANNOUNCERS: THEIR OCCUPATION, BACKGROUND, AND PERSONAL LIFE Michael R. Emrick A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee DUm,s¡ir<y »»itti». UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 11 ABSTRACT From the very early days of radio broadcasting, the descriptions of major league baseball games have been among the more popular types of programs. The relationship between the ball clubs and broadcast stations has developed through experimentation, skepticism, and eventual acceptance. The broadcasts have become financially important to the teams as well as the advertisers and stations. The central person responsible for pleasing the fans as well as satisfying the economic goals of the stations, advertisers, and teams—the principal play- by-play announcer—had not been the subject of intensive study. Contentions were made in the available literature about his objectivity, partiality, and the influence exerted on his description of the games by outside parties. To test these contentions, and to learn more about the overall atmosphere in which this focal person worked, a study was conducted of principal play-by-play announcers who broadcasted games on a day-to-day basis, covering one team for a local audience. With the assistance of some of the announcers, a survey was prepared and distributed to both announcers who were employed in the play-by-play capacity during the 1975 season and those who had been involved in the occupation in past seasons. -

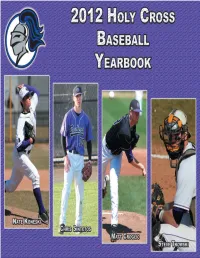

2012 Holy Cross Baseball Yearbook Is Published by Commitment to the Last Principle Assures That the College Secretary:

2 22012012 HOOLYLY CRROSSOSS BAASEBALLSEBALL AT A GLLANCEANCE HOLY CROSS QUICK FACTS COACHING STAFF MISSION STATMENT Location: . .Worcester, MA 01610 Head Coach:. Greg DiCenzo (St. Lawrence, 1998) COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS Founded: . 1843 Career Record / Years: . 93-104-1 / Four Years Enrollment: . 2,862 Record at Holy Cross / Years: . 93-104-1 / Four Years DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS Color: . Royal Purple Assistant Coach / Recruiting Coordinator: The Mission of the Athletic Department of the College Nickname: . Crusaders . .Jeff Kane (Clemson, 2001) of the Holy Cross is to promote the intellectual, physical, Affi liations: . NCAA Division I, Patriot League Assistant Coach: and moral development of students. Through Division I President: . Rev. Philip L. Boroughs, S.J. Ron Rakowski (San Francisco State, 2002) athletic participation, our young men and women student- Director of Admissions: . Ann McDermott Assistant Coach:. Jeff Miller (Holy Cross, 2000) athletes learn a self-discipline that has both present and Offi ce Phone: . (508) 793-2443 Baseball Offi ce Phone:. (508) 793-2753 long-term effects; the interplay of individual and team effort; Director of Financial Aid: . Lynne M. Myers E-Mail Address: . [email protected] pride and self esteem in both victory and defeat; a skillful Offi ce Phone: . (508) 793-2265 Mailing Address: . .Greg DiCenzo management of time; personal endurance and courage; and Director of Athletics: . .Richard M. Regan, Jr. Head Baseball Coach the complex relationships between friendship, leadership, Associate Director of Athletics:. Bill Bellerose College of the Holy Cross and service. Our athletics program, in the words of the Associate Director of Athletics:. Ann Zelesky One College Street College Mission Statement, calls for “a community marked Associate Director of Athletics:. -

The BG News December 10, 2008

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 12-10-2008 The BG News December 10, 2008 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News December 10, 2008" (2008). BG News (Student Newspaper). 8011. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/8011 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ESTABLISHED 1920 A daily independent student press serving THE NEWS the campus and surrounding community Wednesday December 10, 2008 Volume 103. Issue 73 BGSU's business Students use Adderall school recognized to focus A recent study shows By Michelle Bosserman Rodney in an effort to focus, Rogers many college students ' 'he Somethingsnevei i liange.And ■ business turn to the A.D.H.D. lor the University - ( allege ol drug Adderall | Page 5 Business \dministralion the '•ation constant is a good thing. I he ( ollege ol Business n A day to Administration has recent I) an ai i minting major on pai e been recognized b\ Prim eton's tn graduate a semestei earlj call in 'gay' Review as oneol the best busi fell the i ollege ol Business Some people call in ness schools in their 2009 edi \dministration deserved the sick, but today, gays lion Hi the "Best 296 Business award foi all the haul work Schools." It is thi' fifth nine ihey ye put into rile school. -

Ou Know What Iremember About Seattle? Every Time Igot up to Bat When It's Aclear Day, I'd See Mount Rainier

2 Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest Front cover: Tony Conigliaro 'The great things that took place waits in the on deck circle as on all those green fields, through Carl Yastrzemski swings at a Gene Brabender pitch all those long-ago summers' during an afternoon Seattle magine spending a summer's day in brand-new . Pilots/Boston Sick's Stadium in 1938 watching Fred Hutchinson Red Sox game on pitch for the Rainiers, or seeing Stan Coveleski July 14, 1969, at throw spitballs at Vaughn Street Park in 1915, or Sick's Stadium. sitting in Cheney Stadium in 1960 while the young Juan Marichal kicked his leg to the heavens. Back cover: Posing in 1913 at In this book, you will revisit all of the classic ballparks, Athletic Park in see the great heroes return to the field and meet the men During aJune 19, 1949, game at Sick's Stadium, Seattle Vancouver, B.C., who organized and ran these teams - John Barnes, W.H. Rainiers infielder Tony York barely misses beating the are All Stars for Lucas, Dan Dugdale, W.W. and W.H. McCredie, Bob throw to San Francisco Seals first baseman Mickey Rocco. the Northwestern Brown and Emil Sick. And you will meet veterans such as League such as . Eddie Basinski and Edo Vanni, still telling stories 60 years (back row, first, after they lived them. wrote many of the photo captions. Ken Eskenazi also lent invaluable design expertise for the cover. second, third, The major leagues arrived in Seattle briefly in 1969, and sixth and eighth more permanently in 1977, but organized baseball has been Finally, I thank the writers whose words grace these from l~ft) William played in the area for more than a century. -

The American Legion Magazine

THE AMERICAN 2 O c • d U L Y 1975 LEGIONMAGAZINE OUR CRUMBLING ROLE IN THE AMERICAS THE FOURTH OF JULY A Bicentennial Feature • SHOULD THE UNITED STATES ADOPT A 200-MILE SEA LIMIT? 50 YEARS OF AMERICAN LEGION BASEBALL THE PLOT TO STOP THE NEXT FLU EPIDEMIC Seagram's Benchmark salutes The American Legion 57th National Convention, with this commemorative replica of Fort Snelling. As a tribute to Minnesota's historic Fort Snelling, we We think you'll agree it's an exceptional work of crafts- have reproduced this colorful china tower, beautifully manship. And when you get it home you'll discover some- emblazoned in 24 carat gold. thing else. The taste of Seagram's Benchmark. Just lift the You'll find it on sale in August at the National Con- bottle out, pour and enjoy a real premium bourbon. Made vention in Minneapolis. After that it will be available in with the kind of fine craftsmanship that's really hard to limited editions at stores across the country* Then the find these days. mold will be broken and will never be produced again. American Legion, Seagram's Benchmark salutes you! *Void where prohibited. : THE AMERICAN JULY 1975 Volume 99, Number 1 National Commander LEGION James M. Wagonseller MAGAZINE JULY 1975 CHANGE OF ADDRESS Subscribers, please notify Circulation Dept., P. O. Box 1954, Indianapolis, Ind. 46206 using Form 3578 which is available at your Table of Contents local post office. Attach old address label and give old and new addresses with ZIP Code number and current membership card num- ber. -

2014 Baseball Yearbook.Indd

2 2014 HOLY CROSS BASEBALL AT A GLANCE HOLY CROSS QUICK FACTS COACHING STAFF MISSION STATMENT Location: . .Worcester, MA 01610 Head Coach:. Greg DiCenzo (St. Lawrence, 1998) COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS Founded: . 1843 Career Record / Years: . 154-151-1 / Six Years Enrollment: . 2,891 Record at Holy Cross / Years: 154-151-1 / Six Years DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS Color: . Royal Purple E-Mail Address: . [email protected] The Mission of the Athletic Department of the College Nickname: . Crusaders Associate Head Coach Coach / Recruiting Coordinator: of the Holy Cross is to promote the intellectual, physical, Affiliations: . NCAA Division I, Patriot League . .Jeff Kane (Clemson, 2001) and moral development of students. Through Division I President: . Rev. Philip L. Boroughs, S.J. Assistant Coach: athletic participation, our young men and women student- Director of Admissions: . Ann McDermott . Ron Rakowski (San Francisco State, 2002) athletes learn a self-discipline that has both present and Office Phone: . (508) 793-2443 Assistant Coach:. Jeff Miller (Holy Cross, 2000) long-term effects; the interplay of individual and team effort; Director of Financial Aid: . .Lynne Myers Baseball Office Phone:. (508) 793-2753 pride and self esteem in both victory and defeat; a skillful Office Phone: . (508) 793-2265 Mailing Address: . Baseball Office management of time; personal endurance and courage; and Director of Athletics: . Nathan Pine College of the Holy Cross the complex relationships between friendship, leadership, Associate Director of Athletics:. Bill Bellerose One College Street and service. Our athletics program, in the words of the Associate Director of Athletics:. Ann Zelesky Worcester, MA 01610 College Mission Statement, calls for “a community marked Associate Director of Athletics:. -

Inside Baseball Dell Bethel Central Washington University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at Central Washington University Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1964 Inside Baseball Dell Bethel Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Methods Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Bethel, Dell, "Inside Baseball" (1964). All Master's Theses. Paper 371. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. INSIDE BASEBALL A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment ot the Requirements for the Degree &Ster of Education . by Dell Bethel July 1964 ,· .. ; APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ Everett A. Irish, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Albert H. Poffenroth _________________________________ Dohn A. Miller DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this book to my wife who is as splendid an assistant coach as a man could find. Any degree of success I have had has been in a large measure due to her. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the great coaches I have had the pleasure to play under or work with. I have learned much of what I have written in the pages to follow from these men, who through their dedication have made baseball the great game it is today. These men are Bill Bethel, Fred Warburton, Ray Gestault, Ray Ross, Dick Siebert, Andy Gilbert, Frank Shellenback, Carl Hubbell, Bubber Jonnard, Chick Genovese, Tom Heath, Ed Burke, Leo Durocher, Don Kirsch, Cliff Dorow, John Kasper, Dave Kosher, Jim Fitzharris and Rosy Ryan. -

NBC Transmitter.

m NATIONAL EfiOADCASTINQ COMPANY, general library 30 ROCKEFELLER PLAZA, NEW YORK, N. 1 >:.-s Vr-. iS- ’ NBC VOL. 6 JANUARY, 1940 No. 1 LATEST PROGRESS IN TELEVISION NEW YEAR SftS MANY TRAINING FCC VIEWS NEW PORTABLE UNIT GROUPS HELD FOR YOUNGER MEN elevision de- S the New Year ajrproaches and gets underway, it finds T velops so rapid- AI the largest number yet of employe training courses ly that it is always in action. This is a result of the Company’s policy of filling outmoding its own vacancies from its own ranks. It has been said more and news. This month more often in the past few years that the Company is old there are several enough to prepare its personnel to fill the responsible posi- items for the record. tions created or opened as time goes on, and this year a We are all familiar more comprehensve effort than ever is being made in that with the ten-ton, direction. two-truck mobile Ashton Dunn of Personnel has already organized a group unit which has so for the purpose of learning the structure and activities of successfully picked various departments. It is similar to last year’s group which up such nemos as was developed to satisfy the expressed interest of the younger Evolution of an Idea. boxing and tennis employes. Some of the more specialized courses recently matches, and base- planned or begun are working in connection with the larger ball and football games. This sleek monster is the incredi- group to fill out the general training program. -

1922-10-07, [P

12 THt EVENING JOURNAL, SAlUKDAV, OOlObtK 7, 1022 — Scott, Cast-Off Pitcher, Jocko Scott 's Victory r Composite Score of First, Second and Today’s Sport Card Players’ Baseball I is Big Break of Series; Shuts Out Yankees, 3-0; Third Games of World Series BASEBALL Pool Amounts World’s Series to $123,108.90 Allows Only 4 Hits Giants and Yanks Play by Yankees Seem AU In YANKEES play at Th« News-Journal. The official attendance and Bat. Field. City Championship receipts for the third game of By CARL VICTOR LITTLE, and beat him to the bog Grob sln- Player ab r h 2b 3b hr th so bb bp sh sb avg. po a e avg Seventh Ward, City League the world series yesterday, By HENRY L. FARRELL Scott pitched yesterday with con JfUntted Press Staff Correspondent.) gled Into right field. FVsch singled Witt, cf............12 02010431 c (, 0 .167 3 1 0 1.000 champions, and Penney, Indus which follow, ehow a new gate (IT. P. Staff Correspondent.) summate courage and he has Jived NEW YORK. Oct. 7.—The shades •er second. Oroh going to the middle Dugan, 3b. ., 13 2 3 1 0 0 4 1 0 0 0 0 .231 6 4 0 1,000 trial League champlona, Penney receipt record for a »Ingle day: NEW YORK, Oct. 7.—(United a year on the same virtue, Since ? pf night were failing fas: upon the bag. Meusel lined out to Ward, who Ruth, rf. ...11 1 2 X « 0 3 3 1 1 0 0 .132 0 1.000 Field.