VN313 8!Lqnd UB8!J8WV 8~L Pub O! PB~ Aijbj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Oregon State (1-0) Vs. Northwest (0-0) 11/25 California^ W, 71-63 November 27, 2020 • Gill Coliseum • Corvallis, Ore

Men’s Basketball Media Relations Contact - Trevor Cramer • [email protected] Office: 541-737-8898 • 221 Gill Coliseum, Corvallis, OR 97331 • www.osubeavers.com 2020-21 Schedule Date Opponent Time/Result Oregon State (1-0) vs. Northwest (0-0) 11/25 California^ W, 71-63 November 27, 2020 • Gill Coliseum • Corvallis, Ore. 11/27 Northwest^ 10:00 a.m. THE GAME: Oregon State will look for a 2-0 12/2 at Washington St.*^ 7:00 p.m. start to the 2020-21 season Friday, when it Oregon State 12/6 Wyoming^ 2:00 p.m. takes on Northwest at Gill Colisuem. Overall Record ..............................................1-0 12/10 Portland^ 5:00 p.m. Pac-12 Record ........................................ 0-0 12/16 UTSA^ 2:00 p.m. QUICKLY: The Beavers opened the 2020- Home Record ...........................................1-0 12/20 USC*/ TBD Road Record ........................................... 0-0 12/31 Stanford*/ TBD 21 season with a nonconference win over California on Wednesday ... Oregon State Neutral Record ...................................... 0-0 1/2 California*/ TBD is looking to start 2-0 for the third-straight 1/6 at Utah */ TBD season ... Four Beavers scored in double- Northwest 1/9 at Colorado*/ TBD figures Wednesday vs. California ... Warith Overall Record ............................................ 0-0 1/14 Arizona*/ TBD Alatishe scored 16 points in his first Or- Home Record ......................................... 0-0 1/16 Arizona State*/ TBD egon State game, two points short of the 1/23 at Oregon*/ TBD Road Record ........................................... 0-0 OSU record for a junior debut ... The Bea- 1/28 at USC*/ TBD Neutral Record ...................................... 0-0 1/30 at UCLA*/ TBD vers out-rebounded California 43-32, with three Beaves finishing with six or more 2/4 Washington*/ TBD boards .. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

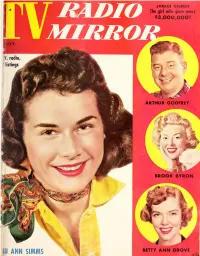

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

EMORIES of Rour I EARS SERVICE

Under the Stars '"'^•Slfc- and Bars ,...o».... MEMORIEEMORIES OF FOUrOUR YI :EAR S SERVICE WITH TiaOR OGLETHORPES OF Jy WAWER A. CI^ARK, •,-'j-^j-rj,--:. j^rtrr.:f-'- H <^1 OR, MEMORIES OF FOUR YEARS SERVICE AVITH THE OGLETHORPES, OF AUGUSTA, GEORGIA BY WALTER A. CLARK, ORDERLY SERGEANT. AUGUSTA, GA Chronicle Printing Company. DEDICATION To the surviving members of the Oglethorpes, with whom I shared the dangers and hardships of soldier life and to the memory of those who fell on the firing line, or from ghostly cots in hospital Avards, with fevered lip and wasted forms, "drifted out on the unknown sea that rolls round all the Avorld," these memories are tenderly and afifectionatelv inscribed bv their old friend and comrade. PREFACE. For the gratification of my old comrades and in grate- hil memory of their constant kindness during all our years of comradeship these records have been written. The Avriter claims no special qualification for the task save as it may lie in the fact that no other survivor of the Company has so large a fund of material from which to draw for such a purpose. In addition to a war journal, whose entries cover all my four years service, nearly every letter Avritten by me from camp in those eventful years has been preserved. WHiatever lack, therefore, these pages may possess on other lines, they furnish at least a truth ful portrait of what I saw and felt as a soldier. It has beeen my purpose to picture the lights rather than the shadoAvs of our soldier life. -

Comments of the National Association of Broadcasters

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) 2018 Quadrennial Regulatory Review -- ) MB Docket No. 18-349 Review of the Commission’s Broadcast ) Ownership Rules and Other Rules Adopted ) Pursuant to Section 202 of the ) Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCASTERS Rick Kaplan Jerianne Timmerman Erin Dozier Patrick McFadden Larry Walke Emily Gomes Daniel McDonald Theresa Ottina Loren White NAB Research September 2, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY .................................................................................... 1 II. THE FCC SHOULD FOCUS IN THS PROCEEDING ON ENSURING THE COMPETITIVE VIABLITY OF LOCAL STATIONS ....................................................................................... 6 III. THE FCC’S DECADES-OLD OWNERSHIP RULES HAVE NEVER SUCCESSFULLY PROMOTED DIVERSE OWNERSHIP OF RADIO AND TELEVISION STATIONS .................. 9 The FCC’s Rules Do Not Address The Central Challenge To New Entry And Diverse Ownership In Broadcasting, Which Is Access To Capital .................... 10 The FCC’s Ownership Rules Affirmatively Undermine Investment In Broadcasting And New Entry ............................................................................ 15 IV. REFORM OF THE OWNERSHIP RULES WOULD PROMOTE LOCALISM BY SAFEGUARDING THE VIABILITY OF LOCAL BROADCAST JOURNALISM IN TODAY’S BIG TECH-DOMINATED MARKETPLACE .............................................................................. 19 The FCC Cannot Ignore The -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 16, No. 06

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus mfeii^^jg«;^<^;gs.^gj5«ggg^^ THE NOTRE DAME ALUMNUS /.. ^ "t^ , ^ i -^m-r '^•P\ if.v,VAY ?..- "^n -<-":-i}. i > "l^.*:- -'/f.^^^, Reunion dates: Si? JUNE 3 -m^^?^ «^.%-. 4 ^ 5 ' •> n> (See program inside] f| 174 The Notre Dame Alumnus May. 1938 sirrs The University acknowledges with deep gratitude the following gifts: From Mr. O. L. Rhoades, Siin Manufacturing Company, Chicago. A sun combustion tester, for the Department of Aeronautical Elngincering. From the Studdiafcer Corporation, South Bend. Two bound folio volumes of photostatic copies of dippings referring to the career of the late Knute Rockne. From: The Rev. John O'Brien, Yonkers, N. Y. Mr. Charles F. McTague^ Montdair, N. J. Mr. Edward L. Boyle, Sr., Duluth, Minn. Reference books for special libraries. From the Library of the University of Virginia. Forty-three volumes, for the College of Engineering. For the Rockne Mennorial E. F. Moran. M?: W. B. Moran, 74; J. R. Moran. Rev. J. A. McShane, Winnebago, Mmn. 10 •25: J. A. Moran. 10: and \V. H. Moran, Rev. Michael P. Seter, Evansville, Ind. ._ 10 Tulsa, Oklahoma $1,000 Rev. William Murray, Chicago, Illinois 10 E. T. Fleming, Dallas, Texas 500 Rev. John P. Donahue. Hopedale, Mass. 10 J. A. LaFortune, '18, Tulsa 500 Rev. John C. Vismara, Detroit, Michigan 10 A. \V. Leonard, •89--93. Tulsa 500 Rev. Martin J. Donlon, Brooklyn. N. Y. 10 J. \V. Simmons, Dallas. Texas 250 Rev. -

Rhythm & Blues Rhythm & Blues S E U L B & M H T Y

64 RHYTHM & BLUES RHYTHM & BLUES ARTHUR ALEXANDER JESSE BELVIN THE MONU MENT YEARS CD CHD 805 € 17.75 GUESS WHO? THE RCA VICTOR (Baby) For You- The Other Woman (In My Life)- Stay By Me- Me And RECORD INGS (2-CD) CD CH2 1020 € 23.25 Mine- Show Me The Road- Turn Around (And Try Me)- Baby This CD-1:- Secret Love- Love Is Here To Stay- Ol’Man River- Now You Baby That- Baby I Love You- In My Sorrow- I Want To Marry You- In Know- Zing! Went The My Baby’s Eyes- Love’s Where Life Begins- Miles And Miles From Strings Of My Heart- Home- You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care)- I Need You Baby- Guess Who- Witch craft- We’re Gonna Hate Ourselves In The Morn ing- Spanish Harlem- My Funny Valen tine- Concerte Jungle- Talk ing Care Of A Woman- Set Me Free- Bye Bye Funny- Take Me Back To Love- Another Time, Another Place- Cry Like A Baby- Glory Road- The Island- (I’m Afraid) The Call Me Honey- The Migrant- Lover Please- In The Middle Of It All Masquer ade Is Over- · (1965-72 ‘Monument’) (77:39/28) In den Jahren 1965-72 Alright, Okay, You Win- entstandene Aufnahmen in seinem eigenwilligen Stil, einer Ever Since We Met- Pledg- Mischung aus Soul und Country Music / his songs were covered ing My Love- My Girl Is Just by the Stones and Beatles. Unique country-soul music. Enough Woman For Me- SIL AUSTIN Volare (Nel Blu Dipinto Di SWINGSATION CD 547 876 € 16.75 Blu)- Old MacDonald (The Dogwood Junc tion- Wildwood- Slow Walk- Pink Shade Of Blue- Charg ers)- Dandilyon Walkin’ And Talkin’- Fine (The Charg ers)- CD-2:- Brown Frame- Train Whis- Give Me Love- I’ll Never -

Hugo Gernsback and Radio Magazines: an Influential Intersection in Broadcast History

Journal of Radio Studies/Volume 9, No. 2, 2002 Hugo Gernsback and Radio Magazines: An Influential Intersection in Broadcast History Keith Massie and Stephen D. Perry Hugo Gernsback's contributions to the devetopment of early radio have gone largely unheralded. This article concentrates on how his role as the most influentiat editor in the 1920s radio press inftuenced earty radio experimentation, regutation, growth, and poputarization. His pubtications promoted radio among hobbyists and novices, but also encouraged experimenters and innovators. He often described ways in which radio could be improved down to the publication of technical diagrams. He built his own radio stations where he tested many of the innovations his magazine promoted. Gernsback's greatest personal satisfaction derived from encouraging broad experimentation that enhanced scientific development. The story of broadcasting involves an amalgam of people who influ- enced its development and direction. Names like Guglielmo Marconi, David Sarnoff, William Paley, Lee De Forest, Reginald Fessenden, Frank Conrad, Alexander Popov, and others have become well known for their work in inventing, developing, and promoting pieces of the puzzle that became the medium of radio. Others have remained no more than historical footnotes. One person who has been little more than a foot- note in broadcasting but whose fame lives on in another area is Hugo Gernsback, the father of science fiction and namesake of the Hugo Award for science fiction writing.^ Yet he may have been one of the most influential figures in promoting radio experimentation and adop- tion by amateur hobbyists in the 1910s and 1920s, and in campaigning for regulatory directions for radio in the days before the establishment of the Federal Radio Commission. -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

Herman Leonard's Stolen Moments June 6,7,8

Volume 36 • Issue 6 June 2008 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. azz musicians perpetually quest for that transcendent instant when thought becomes Herman Leonard’s Jsound, when four minds (or 14) become one, when all the elements — melody, harmony, rhythm, tone color, the club and the audience — conspire toward ineffable Stolen Moments brilliance, when in the words of David Amram, “It’s as if the music were coming from By Jim Gerard | Photos by Herman Leonard somewhere through you and out the end of your horn.1” continued on page 10 Ella Fitzgerald singing to Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman, NYC, 1949, ELF03. © Herman Leonard Photography, LLC 1. Amram, Vibrations (Macmillan, 1968) ARTICLES Caught in the Act . 42 in this issue: Classic Stine. 9 Brubeck at NJPAC . 43 NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Crow’s Nest . 9 M. Maggart/M.C. Haran . 44 Pres Sez/NJJS Calendar Big Band in the Sky . 16 Film: Anita O’Day. 46 Get with Jazzfest! & Bulletin Board. 2 Lang Remembers Ozzie Cadena . 18 Book: Gypsy Jazz . 47 Complete The Mail Bag/Jazz Trivia. 4 Talking Jazz: Les Paul . 20 Film: Tal Farlow . 48 schedule p 50 June 6,7,8 Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info. 6 Yours for a Song . 32 EVENTS Music Committee . 8 Noteworthy . 33 Newark Museum Jazz in the Garden . 49 New Members/About NJJS/ Jazz U: College Jazz . 34 ’Round Jersey: Morris, Ocean . 52 Jazzfest facts, Membership Info . 51 Cape May Jazz Festival . 37 Institute of Jazz Studies/ REVIEWS Jazz from Archives .