Alveolates to the Apicomplexan Obligate Parasites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basal Body Structure and Composition in the Apicomplexans Toxoplasma and Plasmodium Maria E

Francia et al. Cilia (2016) 5:3 DOI 10.1186/s13630-016-0025-5 Cilia REVIEW Open Access Basal body structure and composition in the apicomplexans Toxoplasma and Plasmodium Maria E. Francia1* , Jean‑Francois Dubremetz2 and Naomi S. Morrissette3 Abstract The phylum Apicomplexa encompasses numerous important human and animal disease-causing parasites, includ‑ ing the Plasmodium species, and Toxoplasma gondii, causative agents of malaria and toxoplasmosis, respectively. Apicomplexans proliferate by asexual replication and can also undergo sexual recombination. Most life cycle stages of the parasite lack flagella; these structures only appear on male gametes. Although male gametes (microgametes) assemble a typical 9 2 axoneme, the structure of the templating basal body is poorly defined. Moreover, the rela‑ tionship between asexual+ stage centrioles and microgamete basal bodies remains unclear. While asexual stages of Plasmodium lack defined centriole structures, the asexual stages of Toxoplasma and closely related coccidian api‑ complexans contain centrioles that consist of nine singlet microtubules and a central tubule. There are relatively few ultra-structural images of Toxoplasma microgametes, which only develop in cat intestinal epithelium. Only a subset of these include sections through the basal body: to date, none have unambiguously captured organization of the basal body structure. Moreover, it is unclear whether this basal body is derived from pre-existing asexual stage centrioles or is synthesized de novo. Basal bodies in Plasmodium microgametes are thought to be synthesized de novo, and their assembly remains ill-defined. Apicomplexan genomes harbor genes encoding δ- and ε-tubulin homologs, potentially enabling these parasites to assemble a typical triplet basal body structure. -

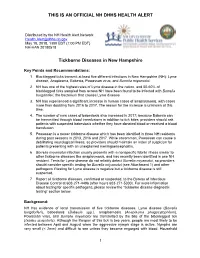

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Molecular Data and the Evolutionary History of Dinoflagellates by Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria Diplom, Ruprecht-Karls-Un

Molecular data and the evolutionary history of dinoflagellates by Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria Diplom, Ruprecht-Karls-Universitat Heidelberg, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Botany We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November 2003 © Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria, 2003 ABSTRACT New sequences of ribosomal and protein genes were combined with available morphological and paleontological data to produce a phylogenetic framework for dinoflagellates. The evolutionary history of some of the major morphological features of the group was then investigated in the light of that framework. Phylogenetic trees of dinoflagellates based on the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (SSU) are generally poorly resolved but include many well- supported clades, and while combined analyses of SSU and LSU (large subunit ribosomal RNA) improve the support for several nodes, they are still generally unsatisfactory. Protein-gene based trees lack the degree of species representation necessary for meaningful in-group phylogenetic analyses, but do provide important insights to the phylogenetic position of dinoflagellates as a whole and on the identity of their close relatives. Molecular data agree with paleontology in suggesting an early evolutionary radiation of the group, but whereas paleontological data include only taxa with fossilizable cysts, the new data examined here establish that this radiation event included all dinokaryotic lineages, including athecate forms. Plastids were lost and replaced many times in dinoflagellates, a situation entirely unique for this group. Histones could well have been lost earlier in the lineage than previously assumed. -

Babesia Species

Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Basic guidelines A. Capillary blood should be obtained by fingerstick, or venous blood should be obtained by venipuncture. B. Blood smears, at least two thick and two thin, should be prepared as soon as possible after col- lection. Delay in preparation of the smears can result in changes in parasite morphology and staining characteristics. In Babesia infections, infected red blood cells (rbcs) are normal in size. Typically rings are seen, and they may be vacuolated, pleomorphic or pyriform. Extracellular or tetrad-forms may also be present. Unlike Plasmodium spp., Babesia organisms lack pigment. Rings Rings of Babesia spp. have delicate cytoplasm and are often pleomorphic. Infected rbcs are not enlarged; multiple infection of rbcs can be common. Rings are usually vacuolated and do not produce pigment. Oc- casional classic tetrad-forms (Maltese Cross) or extracellular rings can be present. Rings of Babesia sp. in thick blood smears. Thin, delicate rings of Babesia sp. in a Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear, Thin blood smear showing a cluster of thin blood smear. showing pleomorphic rings and multiply- extracellular rings. infected rbcs. Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Babesia microti in a thin blood smear. Note Babesia microti in thin blood smears. Notice the vacuolated and pleomorphic rings and multi- the classic “Maltese Cross” tetrad-form in ply-infected rbcs. Notice also there is no pigment present in any of the parasites. the infected rbc in the lower part of the image. Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear stained with Giemsa, showing pleomorphic rings and Babesia sp. -

And Toxoplasmosis in Jackass Penguins in South Africa

IMMUNOLOGICAL SURVEY OF BABESIOSIS (BABESIA PEIRCEI) AND TOXOPLASMOSIS IN JACKASS PENGUINS IN SOUTH AFRICA GRACZYK T.K.', B1~OSSY J.].", SA DERS M.L. ', D UBEY J.P.···, PLOS A .. ••• & STOSKOPF M. K .. •••• Sununary : ReSlIlIle: E x-I1V\c n oN l~ lIrIUSATION D'Ar\'"TIGENE DE B ;IB£,'lA PH/Re El EN ELISA ET simoNi,cATIVlTli t'OUR 7 bxo l'l.ASMA GONIJfI DE SI'I-IENICUS was extracted from nucleated erythrocytes Babesia peircei of IJEMIiNSUS EN ArRIQUE D U SUD naturally infected Jackass penguin (Spheniscus demersus) from South Africo (SA). Babesia peircei glycoprotein·enriched fractions Babesia peircei a ele extra it d 'erythrocytes nue/fies p,ovenanl de Sphenicus demersus originoires d 'Afrique du Sud infectes were obto ined by conca navalin A-Sepharose affinity column natulellement. Des fractions de Babesia peircei enrichies en chromatogrophy and separated by sod ium dodecyl sulphate glycoproleines onl ele oblenues par chromatographie sur colonne polyacrylam ide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE ). At least d 'alfinite concona valine A-Sephorose et separees par 14 protein bonds (9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, electrophorese en gel de polyacrylamide-dodecylsuJfale de sodium 120, 204, and 205 kDa) were observed, with the major protein (SOS'PAGE) Q uotorze bandes proleiques au minimum ont ete at 25 kDa. Blood samples of 191 adult S. demersus were tes ted observees (9, 1 I, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, 120, 204, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assoy (ELISA) utilizing B. peircei et 205 Wa), 10 proleine ma;eure elant de 25 Wo. -

Identification of a Novel Fused Gene Family Implicates Convergent

Chen et al. BMC Genomics (2018) 19:306 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4685-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Identification of a novel fused gene family implicates convergent evolution in eukaryotic calcium signaling Fei Chen1,2,3, Liangsheng Zhang1, Zhenguo Lin4 and Zong-Ming Max Cheng2,3* Abstract Background: Both calcium signals and protein phosphorylation responses are universal signals in eukaryotic cell signaling. Currently three pathways have been characterized in different eukaryotes converting the Ca2+ signals to the protein phosphorylation responses. All these pathways have based mostly on studies in plants and animals. Results: Based on the exploration of genomes and transcriptomes from all the six eukaryotic supergroups, we report here in Metakinetoplastina protists a novel gene family. This family, with a proposed name SCAMK,comprisesSnRK3 fused calmodulin-like III kinase genes and was likely evolved through the insertion of a calmodulin-like3 gene into an SnRK3 gene by unequal crossover of homologous chromosomes in meiosis cell. Its origin dated back to the time intersection at least 450 million-year-ago when Excavata parasites, Vertebrata hosts, and Insecta vectors evolved. We also analyzed SCAMK’s unique expression pattern and structure, and proposed it as one of the leading calcium signal conversion pathways in Excavata parasite. These characters made SCAMK gene as a potential drug target for treating human African trypanosomiasis. Conclusions: This report identified a novel gene fusion and dated its precise fusion time -

![28-Protistsf20r.Ppt [Compatibility Mode]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9929/28-protistsf20r-ppt-compatibility-mode-159929.webp)

28-Protistsf20r.Ppt [Compatibility Mode]

9/3/20 Ch 28: The Protists (a.k.a. Protoctists) (meet these in more detail in your book and lab) 1 Protists invent: eukaryotic cells size complexity Remember: 1°(primary) endosymbiosis? -> mitochondrion -> chloroplast genome unicellular -> multicellular 2 1 9/3/20 For chloroplasts 2° (secondary) happened (more complicated) {3°(tertiary) happened too} 3 4 Eukaryotic “supergroups” (SG; between K and P) 4 2 9/3/20 Protists invent sex: meiosis and fertilization -> 3 Life Cycles/Histories (Fig 13.6) Spores and some protists (Humans do this one) 5 “Algae” Group PS Pigments Euglenoids chl a & b (& carotenoids) Dinoflagellates chl a & c (usually) (& carotenoids) Diatoms chl a & c (& carotenoids) Xanthophytes chl a & c (& carotenoids) Chrysophytes chl a & c (& carotenoids) Coccolithophorids chl a & c (& carotenoids) Browns chl a & c (& carotenoids) Reds chl a, phycobilins (& carotenoids) Greens chl a & b (& carotenoids) (more groups exist) 6 3 9/3/20 Name word roots (indicate nutrition) “algae” (-phyt-) protozoa (no consistent word ending) “fungal-like” (-myc-) Ecological terms plankton phytoplankton zooplankton 7 SG: Excavata/Excavates “excavated” feeding groove some have reduced mitochondria (e.g.: mitosomes, hydrogenosomes) 8 4 9/3/20 SG: Excavata O: Diplomonads: †Giardia Cl: Parabasalids: Trichonympha (bk only) †Trichomonas P: Euglenophyta/zoa C: Kinetoplastids = trypanosomes/hemoflagellates: †Trypanosoma C: Euglenids: Euglena 9 SG: “SAR” clade: Clade Alveolates cell membrane 10 5 9/3/20 SG: “SAR” clade: Clade Alveolates P: Dinoflagellata/Pyrrophyta: -

Bitten Enhance.Pdf

bitten. Copyright © 2019 by Kris Newby. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers, 195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales pro- motional use. For information, please email the Special Markets Department at [email protected]. first edition Frontispiece: Tick research at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, in Hamilton, Mon- tana (Courtesy of Gary Hettrick, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], National Institutes of Health [NIH]) Maps by Nick Springer, Springer Cartographics Designed by William Ruoto Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Newby, Kris, author. Title: Bitten: the secret history of lyme disease and biological weapons / Kris Newby. Description: New York, NY: Harper Wave, [2019] Identifiers: LCCN 2019006357 | ISBN 9780062896278 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Lyme disease— History. | Lyme disease— Diagnosis. | Lyme Disease— Treatment. | BISAC: HEALTH & FITNESS / Diseases / Nervous System (incl. Brain). | MEDICAL / Diseases. | MEDICAL / Infectious Diseases. Classification: LCC RC155.5.N49 2019 | DDC 616.9/246—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006357 19 20 21 22 23 lsc 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Appendix I: Ticks and Human Disease Agents -

The Planktonic Protist Interactome: Where Do We Stand After a Century of Research?

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/587352; this version posted May 2, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Bjorbækmo et al., 23.03.2019 – preprint copy - BioRxiv The planktonic protist interactome: where do we stand after a century of research? Marit F. Markussen Bjorbækmo1*, Andreas Evenstad1* and Line Lieblein Røsæg1*, Anders K. Krabberød1**, and Ramiro Logares2,1** 1 University of Oslo, Department of Biosciences, Section for Genetics and Evolutionary Biology (Evogene), Blindernv. 31, N- 0316 Oslo, Norway 2 Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37-49, ES-08003, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain * The three authors contributed equally ** Corresponding authors: Ramiro Logares: Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM-CSIC), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta 37-49, 08003, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Phone: 34-93-2309500; Fax: 34-93-2309555. [email protected] Anders K. Krabberød: University of Oslo, Department of Biosciences, Section for Genetics and Evolutionary Biology (Evogene), Blindernv. 31, N-0316 Oslo, Norway. Phone +47 22845986, Fax: +47 22854726. [email protected] Abstract Microbial interactions are crucial for Earth ecosystem function, yet our knowledge about them is limited and has so far mainly existed as scattered records. Here, we have surveyed the literature involving planktonic protist interactions and gathered the information in a manually curated Protist Interaction DAtabase (PIDA). In total, we have registered ~2,500 ecological interactions from ~500 publications, spanning the last 150 years. -

4/9/15 1 Alveolates

4/9/15 Bayli Russ ALVEOLATES April 9, 2015 WHAT IS IT? ¡ Alveolates- Major superphylum of protists ¡ Group of single-celled eukaryotes that get their nutrition by predation, photoautotrophy, and intracellular parasitism ¡ Spherical basophilic organisms (6-9 µm diameter) ¡ Most notable shared characteristic is presence of cortical alveoli, flattened vesicles packed into linear layer supporting the membrane, typically forming a flexible pellicle (Leander, 2008) WHAT IS IT? ¡ 3 main subgroups: § Ciliatesà predators that inhabit intestinal tracts and flesh § Dinoflagellatesà mostly free living predators or photoautotrophs, release toxins § Apicomplexansà obligate parasite; invade host cells ¡ Several other lineages such as: § Colpodella § Chromera § Colponema § Ellobiopsids § Oxyrrhis § Rastrimonas § Parvilucifera § Perkinsus (Leander, 2008) 1 4/9/15 HOW DOES IT KILL AMPHIBIANS? ¡ Cause infection and disease in amphibian populations § Infection = parasite occurs in host; occupying intestinal lumen § Disease = advanced infection; presence of spores in tissues; occupying intestinal mucosa, liver, skin, rectum, mesentery, adipose tissue, pancreas, spleen, kidney, and somatic musculature ¡ Effects on organs § Filters into host’s internal organs in mass amounts § Causes organ enlargement and severe tissue alteration § Obliterates kidney and liver structure § System shut-down = DEATH ¡ How its introduced to environment § Birds § Insects ¡ How it spreads/transmission: § Ingestion of spores § Feces of infected individuals § Tissues from dead/dying -

A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia Bigemina

pathogens Communication A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia bigemina Bernardo Sachman-Ruiz 1 , Luis Lozano 2, José J. Lira 1, Grecia Martínez 1 , Carmen Rojas 1 , J. Antonio Álvarez 1 and Julio V. Figueroa 1,* 1 CENID-Salud Animal e Inocuidad, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Jiutepec, Morelos 62550, Mexico; [email protected] (B.S.-R.); [email protected] (J.J.L.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (J.A.Á.) 2 Centro de Ciencias Genómicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, AP565-A Cuernavaca, Morelos 62210, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: fi[email protected]; Tel.: +52-777-320-5544 Abstract: Cattle babesiosis is a socio-economically important tick-borne disease caused by Apicom- plexa protozoa of the genus Babesia that are obligate intraerythrocytic parasites. The pathogenicity of Babesia parasites for cattle is determined by the interaction with the host immune system and the presence of the parasite’s virulence genes. A Babesia bigemina strain that has been maintained under a microaerophilic stationary phase in in vitro culture conditions for several years in the laboratory lost virulence for the bovine host and the capacity for being transmitted by the tick vector. In this study, we compared the virulome of the in vitro culture attenuated Babesia bigemina strain (S) and the virulent tick transmitted parental Mexican B. bigemina strain (M). Preliminary results obtained by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) showed that out of 27 virulence genes described Citation: Sachman-Ruiz, B.; Lozano, and analyzed in the B. -

(Alveolata) As Inferred from Hsp90 and Actin Phylogenies1

J. Phycol. 40, 341–350 (2004) r 2004 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2004.03129.x EARLY EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF DINOFLAGELLATES AND APICOMPLEXANS (ALVEOLATA) AS INFERRED FROM HSP90 AND ACTIN PHYLOGENIES1 Brian S. Leander2 and Patrick J. Keeling Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Program in Evolutionary Biology, Departments of Botany and Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Three extremely diverse groups of unicellular The Alveolata is one of the most biologically diverse eukaryotes comprise the Alveolata: ciliates, dino- supergroups of eukaryotic microorganisms, consisting flagellates, and apicomplexans. The vast phenotypic of ciliates, dinoflagellates, apicomplexans, and several distances between the three groups along with the minor lineages. Although molecular phylogenies un- enigmatic distribution of plastids and the economic equivocally support the monophyly of alveolates, and medical importance of several representative members of the group share only a few derived species (e.g. Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Perkinsus, and morphological features, such as distinctive patterns of Pfiesteria) have stimulated a great deal of specula- cortical vesicles (syn. alveoli or amphiesmal vesicles) tion on the early evolutionary history of alveolates. subtending the plasma membrane and presumptive A robust phylogenetic framework for alveolate pinocytotic structures, called ‘‘micropores’’ (Cavalier- diversity will provide the context necessary for Smith 1993, Siddall et al. 1997, Patterson