Why Has There Been So Little Blockholding in America?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Work in Progress (1999.03.07)

_________________________________________________________________ WORK IN PROGRESS by Cliff Holden ______________________________ Hazelridge School of Painting Pl. 92 Langas 31193 Sweden www.cliffholden.co.uk copyright © CLIFF HOLDEN 2011 2 for Lisa 3 4 Contents Foreword 7 1 My Need to Paint 9 2 The Borough Group 13 3 The Stockholm Exhibition 28 4 Marstrand Designers 40 5 Serigraphy and Design 47 6 Relating to Clients 57 7 Cultural Exchange 70 8 Bomberg's Legacy 85 9 My Approach to Painting 97 10 Teaching and Practice 109 Joseph's Questions 132 5 6 Foreword “This is the commencement of a recording made by Cliff Holden on December 12, 1992. It is my birthday and I am 73 years old. ” It is now seven years since I made the first of the recordings which have been transcribed and edited to make the text of this book. I was persuaded to make these recordings by my friend, the art historian, Joseph Darracott. We had been friends for over forty years and finally I accepted that the project which he was proposing might be feasible and would be worth attempting. And so, in talking about my life as a painter, I applied myself to the discipline of working from a list of questions which had been prepared by Joseph. During our initial discussions about the book Joseph misunderstood my idea, which was to engage in a live dialogue with the cut and thrust of question and answer. The task of responding to questions which had been typed up in advance became much more difficult to deal with because an exercise such as this lacked the kind of stimulus which a live dialogue would have given to it. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

The Breakers Palm Beach - More Than a Century of History

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Sara Flight (561) 659-8465 Bonnie Reuben (310) 248-3852 [email protected] [email protected] The Breakers Palm Beach - More than a Century of History PALM BEACH, FL – The Breakers’ celebrated history is a tribute to its founder, Henry Morrison Flagler, the man who transformed South Florida into a vacation destination for millions. Now into its second century, the resort not only enjoys national and international acclaim, but it continues to thrive under the ownership of Flagler’s heirs. Flagler’s Fortune and Florida’s East Coast When Henry Morrison Flagler first visited Florida in March 1878, he had accumulated a vast fortune with the Standard Oil Company (today Exxon Mobil) in Cleveland and New York as a longtime partner of John D. Rockefeller. In 1882, with the founding of the Standard Oil Trust, the then 52-year-old was earning and able to depend on an annual income of several millions from dividends. Impressed by Florida’s mild winter climate, Flagler decided to gradually withdraw from the company's day-to-day operations and turn his vision towards Florida and his new role of resort developer and railroad king. In 1885, Flagler acquired a site and began the construction of his first hotel in St. Augustine, Florida. Ever the entrepreneur, he continued to build south towards Palm Beach, buying and building Florida railroads and rapidly extending lines down the state's east coast. As the Florida East Coast Railroad opened the region to development and tourism, Flagler continued to acquire or construct resort hotels along the route. -

Flagler's Florida Teacher's Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Letter Sunshine State Standards Guide to Scheduling School Tours Museum Manners Directions and Map to the Museum Lessons and Activities Lesson 1: The Gilded Age and Flagler Museum Overview Pre-Visit Activity & Vocabulary Worksheet Lesson 2: Henry Flagler and American Business Lesson 3: Henry Flagler, Inventor of Modern Florida & Map of Flagler’s Florida Hotels Lesson 4: Whitehall - Florida’s First Museum & Compare/Contrast Chart Lesson 5: The Legacy of Henry Flagler and the Gilded Age Flagler Museum Post-Visit Activity Answer Key to Flagler’s Florida NIE Tab Flagler Museum Post-Visit Questionnaire Flagler Museum Suggested Reading List George G. Matthews Alexander W. Dreyfoos President Trustee G.F. Robert Hanke Kelly M. Hopkins Vice President Trustee William M. Matthews Jesse D. Newman Treasurer Trustee Thomas S. Kenan, III John B. Rogers Secretary Trustee John M. Blades Executive Director Dear Fellow Educators, Thank you for your interest in the Flagler Museum. We are excited that you have chosen to use Flagler’s Florida NIE Tab and Flagler’s Florida Teacher’s Guide to study America’s Gilded Age and Henry Morrison Flagler. You will find that Flagler’s Florida NIE Tab offers a unique glimpse into Florida’s history during the Gilded Age and the role Henry Flagler played in inventing modern Florida. Henry Flagler, founding partner of Standard Oil and developer of Florida’s east coast and the Florida East Coast Railway, was a firm believer in community support and education. Since 1980, the Flagler Museum and its Members have continued this legacy through its support of Florida social studies curriculum and student tours. -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

Vindicating Capitalism: the Real History of the Standard Oil Company

Vindicating Capitalism: The Real History of the Standard Oil Company By Alex Epstein Who were we that we should succeed where so many others failed? Of course, there was something wrong, some dark, evil mystery, or we never should have succeeded!1 —John D. Rockefeller The Standard Story of Standard Oil In 1881, The Atlantic magazine published Henry Demarest Lloyd’s essay “The Story of a Great Monopoly”—the first in- depth account of one of the most infamous stories in the history of capitalism: the “monopolization” of the oil refining market by the Standard Oil Company and its leader, John D. Rockefeller. “Very few of the forty millions of people in the United States who burn kerosene,” Lloyd wrote, know that its production, manufacture, and export, its price at home and abroad, have been controlled for years by a single corporation—the Standard Oil Company... The Standard produces only one fiftieth or sixtieth of our petroleum, but dictates the price of all, and refines nine tenths. This corporation has driven into bankruptcy, or out of business, or into union with itself, all the petroleum refineries of the country except five in New York, and a few of little consequence in Western Pennsylvania... the means by which they achieved monopoly was by conspiracy with the railroads... [Rockefeller] effected secret arrangements with the Pennsylvania, the New York Central, the Erie, and the Atlantic and Great Western... After the Standard had used the rebate to crush out the other refiners, who were its competitors in the purchase of petroleum at the wells, it became the only buyer, and dictated the price. -

Transcript of Interview with Sir Roger Gifford

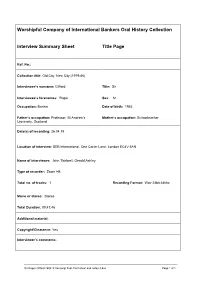

Worshipful Company of International Bankers Oral History Collection Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref. No.: Collection title: Old City, New City (1979-86) Interviewee’s surname: Gifford Title: Sir Interviewee’s forenames: Roger Sex: M Occupation: Banker Date of birth: 1955 Father’s occupation: Professor, St Andrew’s Mother’s occupation: Schoolteacher University, Scotland Date(s) of recording: 26.04.19 Location of interview: SEB International, One Carter Lane, London EC4V 5AN Name of interviewer: John Thirlwell, Gerald Ashley Type of recorder: Zoom H5 Total no. of tracks: 1 Recording Format: Wav 24bit 48khz Mono or stereo: Stereo Total Duration: 00:47:46 Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Yes Interviewer’s comments: Sir Roger Gifford 260419 transcript final, front sheet and notes-3.doc Page 1 of 1 Introduction and biography #00:00:00# Graduate trainee at SG Warburg & Co Ltd; interviewed by #00:01:40# Siegmund Warburg #00:04:53# Banks’ graduate training schemes in the 1970’s i Move to Enskilda Securities (ES); ES’s ‘Big Bang’ structure; #00:06:38# relationship between ES and SEB and Wallenberg family Graduate training schemes in the 1970’s #00:10:15# Working in Enskilda Securities corporate finance #00:11:17# department Culture of the City – ‘the old school tie’; Americanisation of #00:12:38# the City - new capital, new structures Changes of business practice; conflicts of interest #00:19:32# Regulation by the Bank of England #00:21:26# Authorised banks and licensed deposit takers; funding and #00:23:07# growth of Enskilda Securities -

Paradise Reclaimed: the End Of

PARADISE RECLAIMED: THE END OF FRONTIER FLORIDA AND THE BIRTH OF A MODERN STATE, 1900-1940 by SCOTT A. SUAREZ KARI FREDERICKSON, COMMITTEE CHAIR JEFFREY MELTON GEORGE RABLE JOSHUA ROTHMAN LISA DORR A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2016 Copyright Scott A. Suarez 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The question of whether Florida remained a frontier region well into the twentieth century is examined. For the purposes of this study, the concept of a frontier is not based on geography, but on social perception and infrastructural development. Specific areas of interest include disease prevention, the development of roads and railroads, promotional literature, and advertising as a state sponsored business. Data gathered in pursuit of these questions comes from a variety of sources. A broad selection of Florida newspapers are combined with a detailed examination of the papers of several governors, a selection of prominent businessmen and boosters, and the personal recollections of individuals interviewed by the Works Progress Administration. Also included are travel accounts, promotional publications by individual towns and cities, and a selection of photographs and illustrations from the era. There are several limitations on the depth of the research, primarily due to the loss of materials in several disasters, both man-made and natural. The WPA also interviewed only a handful of individuals, resulting in a rather meager selection of recollections. The ultimate conclusion is that Florida was very much a frontier, both physically and psychologically, until the Great Depression of the 1930s. -

Titan: the Life of John D. Rockefeller

Titan: The Life of 207 & 208 John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Reviewed by Robert Schmidt By Ron Chernow About the Author Ron Chernow won the National Book Award in 1990 for his first book, The House of Morgan, and his second book, The Warburgs, won the Eccles Prize as the Best Business Book of 1993. This biography of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., Titan, was a national bestseller and a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist. Other great biographies by Chernow include Alexander Hamilton, Grant, and Washington: A Life. I recommend them all! About the Book From the acclaimed, award-winning author of Alexander Hamilton: here is the essential, endlessly engrossing biography of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.—the Jekyll-and-Hyde of American capitalism. In the course of his nearly 98 years, Rockefeller was known as both a rapacious robber baron, whose Standard Oil Company rode roughshod over an industry, and a philanthropist who donated money lavishly to universities and medical centers. He was the terror of his competitors, the bogeyman of reformers, the delight of caricaturists—and an utter enigma. Drawing on unprecedented access to Rockefeller’s private papers, Chernow reconstructs his subjects’ troubled origins (his father was a swindler and a bigamist) and his single-minded pursuit of wealth. But he also uncovers the profound religiosity that drove him “to give all I could”; his devotion to his father; and the wry sense of humor that made him the country’s most colorful codger. Titan is a magnificent biography—balanced, revelatory, elegantly written. The Book’s ONE THING We study the lives of famous people who have impacted the world in order to better understand our own impact on the world. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

V NFS Form 10400 0MB No. 1014-0019 (Rtv. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form Is for use In nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for Individual properties or districts. See Instructions In Guideline* for Completing National Register Forma (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each Item by marking "x" In the appropriate box or by entering the requested Information. If an Item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategorles listed In the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Green Oove Springs Historic District other names/site number n/a 2. Uocitlon street & number Mil +•• ir"\ j /^ • see attached inventory n/a not for publication city, town Green Oove Sprincrs n/a vicinity state Florida code FL county Clay code 0].9 zlo code 32043 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property j£ private buildlng(s) Noncontrlbutlng ji public-local district 34 .buildings public-State site , sites public-Federal structure , structures object , objects .Total Name of related multiple property Hating: Number of contributing resources previously listed In the National Register 1 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties In the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60. -

Annually Compounded Rate, 46–47 Annual Percentage Rate (APR

Index Note: Page numbers followed by n subprime mortgage crisis, 13, 168, Annually compounded rate, 46–47 indicate notes. 328–329, 355–356, 779–780 Annual percentage rate (APR), 35–38 transparency and, 861–862 Annuities, 28–33. See also Equivalent A Aggarwal, R., 307, 831n annual cost Aghion, P., 841n defined, 28 Aabar Investments, 853 AGL Resources Inc., 84 equivalent annual cash flow, Abandonment option, 254–256, 561–566 Agnblad, I., 856n 141–145 project life and, 564–565 Agrawal, D., 585n, 586n growing, 33–35 temporary, 565–566 AIG, 13, 355, 581 valuation of, 28–33 valuation of, 562–564 Airbus, 253, 567–569, 568n annual mortgage payments, 31–32 ABB, 856, 857 Aivasian, V., 462n annuities due, 31–32 Abnormal return, 318–319 Alcan, 793 future value, 32–33 Absolute priority, 451–452 Alcoa, 806 growing annuities, 33–35 Accelerated depreciation, 136–138, 139 Allayanis, G., 697 installment plan costing, 30 Accelerated underwritings, 377n Allen, Franklin, 163, 226n, 242, 329n, lottery winnings, 30–31 Accenture, 129 358, 409n, 410n, 412, 747–748, Anthony, R., 300n Accounting income, tax income 846n, 860n, 864, 869, 871n, 875n Antikarov, R. S., 572 versus, 137–138 Allen, J., 844 Antitrust law, mergers and, 805–806 Accounting rates of return, 711–713 Allen, L., 594 Aoki, M., 852n nature of, 711–712 Alliant, 834 AOL, 335, 793, 828 problems with, 712–713 Allied Crude Vegetable Oil Refining A&P, 681 Accounting standards, 705 Corporation, 780 Apex One, 793 Accounts payable, 134–135, 738, 740 Allman-Ward, M., 784 Apollo Management, 823 Accounts receivable, 134–135, Allocated overhead, in net present Apple Computer Inc., 369n, 555 733, 737–738, 757 value analysis, 131 Appropriation requests, 241–242 Accrued interest, 600 Alltel, 793 Aramark, 367 Acharya, V. -

Highlights May J U N E /J U

m is “Honoring Tradition, Celebrating Diversity, and Building a Jewish Future” da U form J Re on for I Un E h t r of hIghlIghts be m E Thursday, May 3 at 7:30 pm—PErspectIves on ISraEl. First of a series on Israel and its challenges from viewpoints across the political spectrum. a m This presentation is by Matthew Gabe, AIPAC East Bay Director. See Page 8. is Sunday, May 6 at 10:00 am—annUal MeetIng of thE CongrEgatIon. th El E This event will include election of new officers for the Beth El Board B and a review of the synagogue’s finances. See Page 6 for more details. on I gat Friday, May 11 at 6:15 pm (for appetizers)—CElebratIon of EducatIon honoring Beth El’s E B’nei Mitzvah class, Confirmation class and high school (Midrasha) graduates. Dinner at 6:30 pm with the Shabbat service at 7:30 pm. Join us in celebrating May our students as they lead us in prayer and share with us their insights and reflections. Congr Please sign up for dinner at: https://bethelyouthed.wufoo.com/forms/z7x2s9/ Sunday, May 20 at 10:15 am—MidraSha gradUatIon. Celebrate with the 15 high school students from eight different synagogues who will be graduating this year. For more details, see Page 17. Friday, June 1 at 8:00 pm--CommEmoratIon of thE 100th birthday of raoUl WallEnberg, as one of the Righteous Gentiles who saved a large number of Hungarian Jewish children, including our Emeritus Rabbi Raj, during the Holocaust.