The Cultural Soft Power of China: a Tool for Dualistic National Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 25 Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus Alice Miller In the six months since the 17th Party Congress, Xi Jinping’s public appearances indicate that he has been given the task of day-to-day supervision of the Party apparatus. This role will allow him to expand and consolidate his personal relationships up and down the Party hierarchy, a critical opportunity in his preparation to succeed Hu Jintao as Party leader in 2012. In particular, as Hu Jintao did in his decade of preparation prior to becoming top Party leader in 2002, Xi presides over the Party Secretariat. Traditionally, the Secretariat has served the Party’s top policy coordinating body, supervising implementation of decisions made by the Party Politburo and its Standing Committee. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Xi’s Secretariat has been significantly trimmed to focus solely on the Party apparatus, and has apparently relinquished its longstanding role in coordinating decisions in several major sectors of substantive policy. Xi’s Activities since the Party Congress At the First Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s 17th Central Committee on 22 October 2007, Xi Jinping was appointed sixth-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee and executive secretary of the Party Secretariat. In December 2007, he was also appointed president of the Central Party School, the Party’s finishing school for up and coming leaders and an important think-tank for the Party’s top leadership. On 15 March 2008, at the 11th National People’s Congress (NPC), Xi was also elected PRC vice president, a role that gives him enhanced opportunity to meet with visiting foreign leaders and to travel abroad on official state business. -

Working Paper Series

School of Contemporary Chinese Studies China Policy Institute WORKING PAPER SERIES CPC Elite Perception of the US since the Early 1990s: Wang Huning and Zheng Bijian as Test Cases Niv Horesh Ruike Xu WorkingWP No.2012 Paper-01 No. 24 May 2016 CPC Elite Perception of the US since the Early 1990s: Wang Huning and Zheng Bijian as Test Cases Abstract Scholars of Sino-American relations basically employ two methods to indirectly reveal Chinese policymakers’ perceptions of the US. First, some scholars make use of public opinion polls which survey the general public’s attitudes towards the US. Second, there are nowadays more Western scholars who study China’s ‘America watchers’ and their perceptions of the US by making use of interviews and/or textual analysis of their writings. The American watchers on whom they focus include academics in Chinese Universities, journalists and policy analysts in government and government-affiliated research institutions. What makes this paper distinct from previous research is that it juxtaposes two of the most influential yet under-studied America watchers within the top echelon of the CPC, Wang Huning and Zheng Bijian. To be sure, the two have indelibly shaped CPC attitudes, yet surprisingly enough, although Zheng has been written about extensively in the English language, Wang has hitherto largely remained outside academics’ purview. This paper also aims, in passing, to explore linkages between Wang and Zheng ideas and those of other well- known America watchers like Liu Mingfu and Yan Xuetong. It is hoped that this comparison will offer clues as to the extent to which the current advisory shaping CPC thinking on the US differs from the previous generation, and as to whether CPC thinking is un-American or anti-American in essence. -

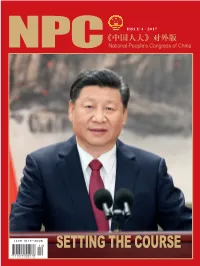

Setting the Course

ISSUE 4 · 2017 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China SETTING THE COURsE General Secretary Xi Jinping (1st L) and other members of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the 19th CPC Central Committee Li Keqiang (2nd L), Li Zhanshu (3rd L), Wang Yang (4th L), Wang Huning (3rd R), Zhao Leji (2nd R) and Han Zheng (1st R), meet the press after being elected on Octo- ber 25, 2017. Ma Zhancheng SPECIAL REPORT 6 New CPC leadership for new era Contents 19th CPC National Congress Special Report In-depth 28 6 26 President Xi Jinping steers New CPC leadership for new era Top CPC leaders reaffirm mission Chinese economy toward 12 at Party’s birthplace high-quality development Setting the course Focus 20 Embarking on a new journey 32 National memorial ceremony for 24 Nanjing Massacre victims Grand design 4 NATIONAL PeoPle’s CoNgress of ChiNa NPC President Xi Jinping steers Chinese 28 economy toward high-quality development 37 National memorial ceremony for 32 Nanjing Massacre victims Awareness of law aids resolution ISSUE 4 · 2017 36 Legislation Chairman Zhang Dejiang calls for pro- motion of Constitution spirit 44 Encourage and protect fair market 38 competition China’s general provisions of Civil NPC Law take effect General Editorial Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, Xicheng District Beijing 39 100805,P.R.China Tibetan NPC delegation visits Tel: (86-10)6309-8540 Canada, Argentina and US (86-10)8308-3891 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of ISSN 1674-3008 Supervision China (CPC), speaks when meeting the press at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Oc- CN 11-5683/D tober 25, 2017. -

Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China Haig Patapan

The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China Author Patapan, Haig, Wang, Yi Published 2018 Journal Title Journal of Contemporary China Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2017.1363018 Copyright Statement © 2017 Taylor & Francis (Routledge). This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Contemporary China on 21 Aug 2017, available online: http:// www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10670564.2017.1363018 Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/348664 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China Haig Patapan and Yi Wang1 Griffith Univesity, Australia Abstract The article provides the first comprehensive examination of the life and thought of Wang Huning, member of the Politburo, advisor to three Chinese leaders and important contributor to major political conceptual formulations in contemporary China. In doing so, it seeks to derive insights into the role of intellectuals in China, and what this says about Chinese politics. It argues that, although initially reluctant to enter politics, Wang has become in effect a ‘hidden leader’, exercising far-reaching influence on the nature of Chinese politics, thereby revealing the fundamental tensions in contemporary Chinese politics, shaped by major political debates concerning stability, economic growth, and legitimacy. Understanding the character and aspirations of China’s top leaders and the subtle and complex shifting of alliances and authority that characterizes politics at this highest level has long been the focus of students of Chinese politics. But much less attention is paid to those who advise these leaders, perhaps because of the anonymity of these advisors and the view that they wield limited authority within the hierarchy of the state and the Party. -

The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report March 23, 2012 The China Rising Leaders Project, Part 1: The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders by John Dotson USCC Research Coordinator With Supporting Research and Contributions By: Shelly Zhao, USCC Research Fellow Andrew Taffer, USCC Research Fellow 1 The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission China Rising Leaders Project Research Report Series: Part 1: The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders (March 2012) Part 2: China’s Emerging Leaders in the People’s Liberation Army (forthcoming June 2012) Part 3: China’s Emerging Leaders in State-Controlled Industry (forthcoming August 2012) Disclaimer: This report is the product of professional research performed by staff of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, and was prepared at the request of the Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 108-7. However, the public release of this document does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission, any individual Commissioner, or the Commission’s other professional staff, of the views or conclusions expressed in this staff research report. Cover Photo: CCP Politburo Standing Committee Member Xi Jinping acknowledges applause in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People following his election as Vice-President of the People’s Republic of China during the 5th plenary session of the National People's Congress (March 15, 2008). -

Standing Committee (In Rank Order) Remaining Members from the 18Th Central Committee Politburo

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) 19th Central Committee Politburo Standing Committee (in rank order) Remaining members from the 18th Central Committee Politburo New members to the 19th Central Committee Politburo The Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) is comprised of the CCP’s top- ranking leaders and is China’s top decision-making body within the Politburo. It meets more frequently and often makes XI JINPING LI KEQIANG LI ZHANSHU WANG YANG WANG HUNING ZHAO LEJI HAN ZHENG key decisions with little or no input from 习近平 李克强 栗战书 汪洋 王沪宁 赵乐际 韩正 the full Politburo. The much larger Central President; CCP General Premier, State Council Chairman, Chairman, Director, Office of CCP Secretary, CCP Central Executive Vice Premier, Secretary; Chairman, CCP Born 1953 Standing Committee of Chinese People’s Political Comprehensively Deepening Discipline Inspection State Council Committee is, in theory, the executive Central Military Commission National People’s Congress Consultative Conference Reform Commission Commission Born 1954 organ of the party. But the Politburo Born 1953 Born 1950 Born 1955 Born 1955 Born 1957 exercises its functions and authority except the few days a year when the Members (in alphabetical order) Central Committee is in session. At the First Session of the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018, Wang Qishan was elected as the Vice President of China. The vice presidency enables Wang to be another important national leader without a specific party portfolio. But in China’s official CCP pecking order, CAI QI CHEN MIN’ER CHEN -

The 7 Men Who Will Run China What You Need to Know About the Members of the 19Th Politburo Standing Committee

FEATURES | POLITICS | EAST ASIA The 7 Men Who Will Run China What you need to know about the members of the 19th Politburo Standing Committee. By Bo Zhiyue October 25, 2017 New members of the Politburo Standing Committee, from left, Han Zheng, Wang Huning, Li Zhanshu, Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Wang Yang, Zhao Leji stand together at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People (Oct. 25, 2017). Credit: AP Photo/Ng Han Guan At its First Plenum on October 25, 2017, the 19th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elected members of the Politburo Standing Committee. As widely expected, among the seven members of the 18th Politburo Standing Committee, four (Zhang Dejiang, Yu Zhengsheng, Liu Yunshan, and Zhang Gaoli) retired due to their age; and two (Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang) were re-elected. As for the final member, contrary to the speculation that Wang Qishan might stay on, he also stepped down possibly because of his age. The following is the new line-up of the 19th Politburo Standing Committee members. No. 1: Xi Jinping President Xi Jinping, 64, was re-elected as general secretary of the CCP Central Committee and No. 1 ranking member of the 19th Politburo Standing Committee as well as chairman of the Central Military Committee. The core of the CCP and Commander-in-Chief of the People’s Liberation Army, Xi has further consolidated his power over the Party at the 19th Party Congress after his thought, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” was enshrined in the CCP Constitution as a “long-term guide to action that the Party must adhere to and develop” along with Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents (Jiang Zemin’s contribution), and the Scientific Outlook on Development (Hu Jintao’s). -

Wang Huning 王沪宁 Born 1955

Wang Huning 王沪宁 Born 1955 Current Positions • Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2017–present) • Executive Secretary of the Secretariat of the CCP Central Committee (2017– present) • Director of the Central Policy Research Center of the CCP Central Committee (2002–present) • Secretary-General (Chief of Staff) and Director of the General Office of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2013–present) • Member of the Politburo (2012–present) • Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present) Personal and Professional Background Wang Huning was born on October 6, 1955, in Shanghai. His ancestral/family home is in Laizhou County, Shandong Province. Wang joined the CCP in 1984. He studied French language as part of the Cadre Training Class at Shanghai Normal University in Shanghai (1972–77) and attended the graduate program in international politics at Fudan University in Shanghai (1978–81), where he also received a master’s degree in law (1981). He has been a visiting scholar at the University of Iowa, the University of Michigan, and the University of California at Berkeley (1988–89). He speaks French fluently. Wang began his career as a cadre in the Publication Bureau of the Shanghai municipal government (1977–78). After receiving his master’s, he stayed on at Fudan University and served as an instructor, associate professor, and professor (1981–89), then as chairman of the Department of International Politics (1989–94), and finally as dean of the law school (1994–95). Wang moved to Beijing in 1995 and served as head of the Political Affairs Division of the Central Policy Research Center (CPRC) of the CCP Central Committee (1995–98), followed by a position as deputy director of the CPRC (1998–2002). -

The People's Liberation Army General Political Department

The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao October 14, 2013 Cover image and below: Chinese nuclear test. Source: CCTV. | Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Political Warfare | About the Project 2049 Institute Cover image source: 997788.com. Above-image source: ekooo0.com The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide Above-image caption: “We must liberate Taiwan” decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. The organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region- specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. www.project2049.net 1 | Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Political Warfare | TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….……………….……………………….3 Universal Political Warfare Theory…………………………………………………….………………..………………4 GPD Liaison Department History…………………………………………………………………….………………….6 Taiwan Liberation Movement…………………………………………………….….…….….……………….8 Ye Jianying and the Third United Front Campaign…………………………….………….…..…….10 Ye Xuanning and Establishment of GPD/LD Platforms…………………….……….…….……….11 GPD/LD and Special Channel for Cross-Strait Dialogue………………….……….……………….12 Jiang Zemin and Diminishment of GPD/LD Influence……………………….…….………..…….13 -

The 19Th Central Committee Politburo

The 19th Central Committee Politburo Alice Miller The 19th CCP Congress and the new Central Committee it elected followed longstanding norms in appointing a new party Politburo. The major exception was the failure to appoint candidates to the Politburo Standing Committee who would succeed to the posts of party general secretary and PRC premier n 2022. Appointments to the new Politburo and its standing committee, as well as to other top leadership bodies, emerged from the 19th Central Committee’s First Plenum on 25 October 2017, as reported by the plenum communiqué and as transmitted by the state news agency Xinhua the same day. The 19th Central Committee was itself elected at 19th CCP Congress, held 18-24 October, which also heard reports on the work of the outgoing 18th Central Committee and Central Commission for Discipline Inspection delivered by General Secretary Xi Jinping and by party discipline chief Wang Qishan, respectively. The New Politburo As Table 1 shows, the turnover of members from the outgoing Politburo to the new one rivals the generational transfer of membership at the last party congress in 2012 and exceeds that at the last mid-term party congress, the 17th in 2007. Including former Chongqing party boss Sun Zhengcai, who was removed for corruption in the months preceding the 19th Congress, 15 members of the 18th Central Committee Politburo stepped down and were replaced by 15 new members. Table 1: Turnover of Politburo Members, 2002-2017 2002 2007 2012 2017 Politburo (total) 14 of 22 13 of 25 15 of 25 15 of 25 Standing Committee 6 of 7 4 of 9 7 of 9 5 of 7 Regular members 8 of 15 9 of 16 8 of 16 10 of 18* *Includes Sun Zhengcai. -

The “Shanghai Gang”: Force for Stability Or Cause for Conflict?* Cheng Li

The “Shanghai Gang”: Force for Stability or Cause for Conflict?* Cheng Li Of all the issues enmeshed in China’s on-going political succession, one of the most intriguing concerns the prospects of the so-called “Shanghai gang” associated with party leader Jiang Zemin. The future of the “Shanghai gang” will determine whether Jiang will continue to play a behind-the-scenes role as China’s paramount leader after retiring as party general secretary at the Sixteenth Party Congress in the fall of 2002. More importantly, contention over the future of the “Shanghai gang” constitutes a critical test of whether China can manage a smooth political succession, resulting in a more collective and power-sharing top leadership. The term “Shanghai gang” (Shanghai bang) refers to current leaders whose careers have advanced primarily due to their political association with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Jiang Zemin in Shanghai. When Jiang Zemin served as mayor and party chief in the city during the mid-1980s, he began to cultivate a web of patron-client ties based on his Shanghai associates. After becoming the party’s top leader in 1989, Jiang appointed several of his confidants in Shanghai to important positions in Beijing. Jiang will likely try to promote more of his protégés from Shanghai to the national leadership at the Sixteenth Party Congress in the fall of 2002 and the Ninth National People’s Congress (NPC) in the spring of 2003. The recent promotion of Shanghai Vice Mayor Chen Liangyu to acting mayor of the city and the transfer of Shanghai CCP Deputy Secretary Meng Jianzhu to become party secretary in Jiangxi province are a prelude to the power jockeying. -

Post-19Th-Party-Cong

HOW THE CCP RULES: MILITARY ANTI-CORRUPTION PARTY AFFAIRS CHINA’S LEADERSHIP AFTER THE 19TH PARTY Zhang Chunxian MASS ORGANIZATIONS CONGRESS Current position unclear 64 NOTE: ONLY 19TH CCP-CC MEMBERS DISPLAYED Liu Qibao KEY: Current position unlcear 64 Huang Kunming S “The Core” of the Leadership Director, CCP-CC Wei Fenghe Propaganda Member, CMC; Department Members of the CCP-CC Politburo Standing State Councilor, Minister 61 of National Defense? Yang Xiaodu S Committee (PSC) (National rank) 63 1st Ranked Vice Secretary, CCDI Chen Xi S Ding Xuexiang S Shen Yueyue Members of the CCP-CC Politburo (PB) 64 Director, CCP- Director, CCP-CC (Vice Chair, NPC-SC; (Vice-National rank) CC Organization General Office Chair, All-China Women’s Xu Qiliang Department 55 Federation) Vice Chair, CMC 64 60 Other Leaders of Party and State (non-PSC or PB 67 leaders ranked Vice-National or above) Zhang Youxia (Non-CCP heads of Mass Vice Chair, CMC Org. not individually listed) Name 67 Position Name, position, and age of leader 6 Age FOREIGN POLICY Zhao Leji Yang Jiechi Secretary, 5 Wang Huning (State Councillor in charge 1st Ranked Secretary, 1 Official order of PSC Members CCDI S of Foreign, Taiwan, Hong 60 CCP-CC Secretariat Kong, and Macau Affairs) (Director, CCP-CC S Secretary, CCP-CC Secretariat (Vice-National rank) 67 Policy Research Office) 62 ( ) Current position from pre-19th Party Congress Liu He 1 ??Director, CCP-CC Policy Research Office?? || 1st Ranked Vice Chair, PRC People’s Republic of China XI JINPING LEGISLATURE (Director, Office of the