Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'China Alternative'?

Asia Pacific: Perspectives ∙ November 2011 http://www.usfca.edu/pacificrim/perspectives/ Downloaded from Asia Pacific: Perspectives ∙ November 2011 Asia Pacific: Perspectives EDITORIAL BOARD Editors Joaquin L. Gonzalez, University of San Francisco John K. Nelson, University of San Francisco Managing Editor Dayna Barnes, University of San Francisco Editorial Consultants Hartmut Fischer, University of San Francisco Editorial Board Uldis Kruze, University of San Francisco Man-lui Lau, University of San Francisco Mark Mir, University of San Francisco Noriko Nagata, University of San Francisco Stephen Roddy, University of San Francisco Kyoko Suda, University of San Francisco Bruce Wydick, University of San Francisco http://www.usfca.edu/pacificrim/perspectives/ University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Angelina Chun Yee, Professor and Executive Director Downloaded from Asia Pacific: Perspectives ∙ November 2011 Asia Pacific: Perspectives Volume 10, Number 2 • November 2011 ARTICLES Editors’ Note >>...............Joaquin Jay Gonzalez and John Nelson 102 Beyond the Hot Debate: Social and Policy Implications of Climate Change in Australia >>........Lawrence Niewójt and Adam Hughes Henry 103 Public Perceptions and Democratic Development in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region >>.........................................Jordin Montgomery 117 Tensions Over Hydroelectric Developments in Central Asia: Regional Interdependence and Energy Security >>.............................Katherine J. Bowen-Williams 133 The ‘China Alternative’? -

Vice President's Meeting with People's Republic of China Vice Premier

W':' S C1 i NG'ON <!fOP ::!f!C~ / SENSITIVE / EYES ONLY MEMO~~DUM OF CONVERSA~ION SUBJECT: S~~ary of the Vice President ' s Meeting with People's Republic of China Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping PARTICIPP.. NTS : Vice President Walter Mondale Leonard Woodcock, U.S. Ambassador to the People's Republic of China David Aaron, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affa~rs Richard Moe, Chief of Staff to the Vice President Denis Clift, Assistant to the Vice President for National Security Affairs Richard Holbrooke, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affair Michel Oksenberg, St"_aff Member I NSC Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping Huang Hua, Minister of Foreign Affairs Chai Zemin, People's Republic of China Ambassador to the United States Zhang Wenjin, Deputy Foreign Minister Han Xu, Director of American Depar~~ent Wei Yongqing, Director of Protocol Ji Chaozhu, Deputy Director of American Depart.:nent DATE, TD1E August 28, 1979; 9:30 a.m. - 12:00 Noon k'lD PLACE: The Great Hall of the People, Beijing, People's Republic of China Vi=e Premier Deng: I heard your speech ;vas war:nly ;.;elcomed. Vice ?res:":ient ~oncale: I W2.S thril2.ed by t.he opportunity to spea2< at your great unive.r·sity anc. -='0 speak to the people. It was an unprecedented occasion, and I t.hank you for that. cpport"..lni ty. DECLASSIFIED \E.O.12958, Sec.3.6 :~_R--I.~~__ NA~ ::T~31m;:J" ,TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE/ EYES ONLY 2 Vice Premier Deng: It was published in full in today ' s People's Daily. -

China Nuclear Chronology

China Nuclear Chronology 2011-2010 | 2009-2008 | 2007-2005 | 2004-2002 | 2001 | 2000-1999 | 1998-1997 | 1996-1995 1994-1992 | 1991-1990 | 1989-1985 | 1984-1980 | 1979-1970 | 1969-1960 | 1959-1945 Last update: July 2011 2011-2010 14 June 2011 China completes nuclear inspections of all 13 currently operating power reactors. According to Li Ganjie, Vice- Minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, safety evaluations of the 28 reactors under construction should be completed by October. Six weeks earlier, China declared its military nuclear facilities safe. Li emphasizes that the lessons from "Japan's Fukushima nuclear crisis are profound," and that China is working on a comprehensive and effective nuclear safety plan. Li confirms that China still plans to construct more than 100 reactors by 2020. On the other hand, "[China] needs to control the pace of [the nuclear energy] development," according to Zheng Yuhui, director of the research center of the China Nuclear Energy Association. The Chinese Academy of Sciences scholars add that China should maintain a relatively stable policy for nuclear power development and further strengthen nuclear safety. —中华人民共和国中央人民政府 [The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China], "环境保护部副部长会见美国能源部核能助理部长 [Vice-Minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Met the United States Department of Energy's Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy]," 14 June 2011, www.gov.cn; "After Inspections, China Moves Ahead with Nuclear Plans," The New York Times, 17 June 2011; "China Suspends New Nuclear Plant Approvals," China Daily (Edition in English), 15 June 2011, www.chinadialy.com; "China May Resume Giving Approvals to New Nuclear Plants-Official," BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, 25 June 2011; "Experts: China Should Keep Nuclear Power Policy Stable," People's Daily (Edition in English), 25 May 2011; "Chinese Military Nuke Facilities Declared Safe," Global Security Newswire, 1 April 2011, www.gsn.nti.org. -

Xpeng Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-39466 XPeng Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Cayman Islands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) No. 8 Songgang Road, Changxing Street Cencun, Tianhe District, Guangzhou Guangdong 510640 People’s Republic of China (Address of principal executive offices) Hongdi Brian Gu, Vice Chairman and President Telephone: +86-20-6680-6680 Email: [email protected] At the address of the Company set forth above (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares, each representing XPEV New York Stock Exchange two Class A ordinary shares Class A ordinary shares, par value US$0.00001 New York Stock Exchange per share* * Not for trading, but only in connection with the listing on the New York Stock Exchange of American depositary shares. -

Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 25 Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus Alice Miller In the six months since the 17th Party Congress, Xi Jinping’s public appearances indicate that he has been given the task of day-to-day supervision of the Party apparatus. This role will allow him to expand and consolidate his personal relationships up and down the Party hierarchy, a critical opportunity in his preparation to succeed Hu Jintao as Party leader in 2012. In particular, as Hu Jintao did in his decade of preparation prior to becoming top Party leader in 2002, Xi presides over the Party Secretariat. Traditionally, the Secretariat has served the Party’s top policy coordinating body, supervising implementation of decisions made by the Party Politburo and its Standing Committee. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Xi’s Secretariat has been significantly trimmed to focus solely on the Party apparatus, and has apparently relinquished its longstanding role in coordinating decisions in several major sectors of substantive policy. Xi’s Activities since the Party Congress At the First Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s 17th Central Committee on 22 October 2007, Xi Jinping was appointed sixth-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee and executive secretary of the Party Secretariat. In December 2007, he was also appointed president of the Central Party School, the Party’s finishing school for up and coming leaders and an important think-tank for the Party’s top leadership. On 15 March 2008, at the 11th National People’s Congress (NPC), Xi was also elected PRC vice president, a role that gives him enhanced opportunity to meet with visiting foreign leaders and to travel abroad on official state business. -

Setting the Course

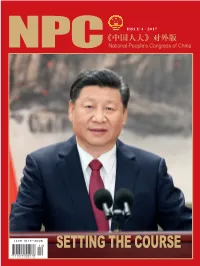

ISSUE 4 · 2017 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China SETTING THE COURsE General Secretary Xi Jinping (1st L) and other members of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the 19th CPC Central Committee Li Keqiang (2nd L), Li Zhanshu (3rd L), Wang Yang (4th L), Wang Huning (3rd R), Zhao Leji (2nd R) and Han Zheng (1st R), meet the press after being elected on Octo- ber 25, 2017. Ma Zhancheng SPECIAL REPORT 6 New CPC leadership for new era Contents 19th CPC National Congress Special Report In-depth 28 6 26 President Xi Jinping steers New CPC leadership for new era Top CPC leaders reaffirm mission Chinese economy toward 12 at Party’s birthplace high-quality development Setting the course Focus 20 Embarking on a new journey 32 National memorial ceremony for 24 Nanjing Massacre victims Grand design 4 NATIONAL PeoPle’s CoNgress of ChiNa NPC President Xi Jinping steers Chinese 28 economy toward high-quality development 37 National memorial ceremony for 32 Nanjing Massacre victims Awareness of law aids resolution ISSUE 4 · 2017 36 Legislation Chairman Zhang Dejiang calls for pro- motion of Constitution spirit 44 Encourage and protect fair market 38 competition China’s general provisions of Civil NPC Law take effect General Editorial Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, Xicheng District Beijing 39 100805,P.R.China Tibetan NPC delegation visits Tel: (86-10)6309-8540 Canada, Argentina and US (86-10)8308-3891 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of ISSN 1674-3008 Supervision China (CPC), speaks when meeting the press at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Oc- CN 11-5683/D tober 25, 2017. -

Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China Haig Patapan

The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China Author Patapan, Haig, Wang, Yi Published 2018 Journal Title Journal of Contemporary China Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2017.1363018 Copyright Statement © 2017 Taylor & Francis (Routledge). This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Contemporary China on 21 Aug 2017, available online: http:// www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10670564.2017.1363018 Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/348664 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China Haig Patapan and Yi Wang1 Griffith Univesity, Australia Abstract The article provides the first comprehensive examination of the life and thought of Wang Huning, member of the Politburo, advisor to three Chinese leaders and important contributor to major political conceptual formulations in contemporary China. In doing so, it seeks to derive insights into the role of intellectuals in China, and what this says about Chinese politics. It argues that, although initially reluctant to enter politics, Wang has become in effect a ‘hidden leader’, exercising far-reaching influence on the nature of Chinese politics, thereby revealing the fundamental tensions in contemporary Chinese politics, shaped by major political debates concerning stability, economic growth, and legitimacy. Understanding the character and aspirations of China’s top leaders and the subtle and complex shifting of alliances and authority that characterizes politics at this highest level has long been the focus of students of Chinese politics. But much less attention is paid to those who advise these leaders, perhaps because of the anonymity of these advisors and the view that they wield limited authority within the hierarchy of the state and the Party. -

China's Peaceful Rise” Sponsored by the John L

Zheng Bijian, Chairman of the China Reform Forum Luncheon Speech at a forum on “China's Peaceful Rise” sponsored by the John L. Thornton China Center Thursday, June 16, 2005 1:00 PM to 3:00 PM Somers Room The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, DC Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Friends, It is a great pleasure for me to visit Washington again and come to the Brookings Institution, an important think tank of the United States, to exchange views with you. I hope that our dialogue will lead to better mutual understanding, more common ground, greater mutual trust and less misgiving in the interest of more positive and stable China- US relations. I know there have been heated discussions in recent years within the US political circle, major think tanks and media on whether or not China's peaceful rise will threaten the American global interests. Some important, constructive, enlightening and interesting viewpoints have been presented. I hope my speech would contribute to the discussion. However, let me assure you that I am not here to debate with you. I just want to talk about solid facts rather than abstract concepts in the following ten points. First, what has happened in the past two decades and more shows that China's peaceful rise is not a threat but an opportunity for the US. Since China began to pursue the reform and opening up policy in the late 1970s, it has opted for a road of seeking a peaceful international environment for development and, by its own development, contributing to the maintenance of world peace. -

The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report March 23, 2012 The China Rising Leaders Project, Part 1: The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders by John Dotson USCC Research Coordinator With Supporting Research and Contributions By: Shelly Zhao, USCC Research Fellow Andrew Taffer, USCC Research Fellow 1 The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission China Rising Leaders Project Research Report Series: Part 1: The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders (March 2012) Part 2: China’s Emerging Leaders in the People’s Liberation Army (forthcoming June 2012) Part 3: China’s Emerging Leaders in State-Controlled Industry (forthcoming August 2012) Disclaimer: This report is the product of professional research performed by staff of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, and was prepared at the request of the Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 108-7. However, the public release of this document does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission, any individual Commissioner, or the Commission’s other professional staff, of the views or conclusions expressed in this staff research report. Cover Photo: CCP Politburo Standing Committee Member Xi Jinping acknowledges applause in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People following his election as Vice-President of the People’s Republic of China during the 5th plenary session of the National People's Congress (March 15, 2008). -

China Threat Theory: a Cultural Institutional Perspective on the Mass Media Coverage of the 19Th Congress

Araştırma Makalesi/Research Article CHINA THREAT THEORY: A CULTURAL INSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE MASS MEDIA COVERAGE OF THE 19TH CONGRESS ÇİN TEHDİDİ TEORİSİ: 19. KONGRE İLE İLGİLİ KİTLE İLETİŞİM ARAÇLARINDA YAPILAN HABERLERE KÜLTÜREL KURUMSALCI BİR BAKIŞ Hakan CAVLAK* Mert ÇETİN** Abstract Öz This study examines the skepticism of the Western Bu çalışmada Batılı toplumların Çin‟in büyümesine societies towards China‟s growth which manifests itself yönelik şüphecilikleri Batı kitle iletişim araçlarında Çin on the Western mass media coverage of the Chinese Komünist Partisi‟nin 19. Kongresi hakkında yapılan Communist Party‟s 19th congress based on cultural- haberler üzerinden kültürel-kurumsalcı yaklaşımla institutional approach. Cultural-institutional perspective incelenmiştir. Kültürel Kurumsalcı yaklaşım ayrıca Çin‟in of China Threat theory which is offering more appropriate tarihsel deneyimlerinin bir sonucu olarak Batı yarımküre arguments emphasizes China‟s non-democratic, karşısında duyduğu güvensizliğin incelenmesini de authoritarian political system. It also examines the sağlamaktadır. Çalışmada ayrıca Çin‟in tarihi deneyimleri insecurity of China towards the Western hemisphere due nedeniyle Batı yarıküreye karşı duyduğu güvensizlik de to its historical experiences. It is argued that China did not değerlendirilmiştir. Bu çalışmada Çin‟in 19. Kongre leave the peaceful development policy after the 19th sonrasında da 2003 yılından beri dış politikasının temelini congress which has dominated China‟s foreign policy oluşturan barışçı kalkınma politikasından vazgeçmediği since 2003. Chinese policy towards North Korean Crisis iddia edilmektedir. Çin‟in Kuzey Kore krizine yönelik has been chosen as the case for supporting the arguments politikası bu argümanı desteklemek üzere örnek olay of the study. olarak alınmıştır. Keywords: Cultural-Institutionalism, Peaceful Anahtar Kelimeler: Kültürel – Kurumsalcılık, Barışçıl Development, Mass Media, 19th Congress, Chinese Kalkınma, Kitle İletişim Araçları, 19. -

Peaceful Rise”

The Journal of the Royal Institute of Thailand Volume II - 2010 Public Opinion and the Limit of China’s “Peaceful Rise” Sitthiphon Kruarattikan Ph.D. Candidate (Integrated Science), College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Thammasat University Abstract Public opinion has played an important role in the making of Chinese foreign policy since Deng Xiaoping’s institution of economic reform in 1978. Chinese citizens, with the coming of commercialized media and information technology, have more latitude to express their own views on international affairs, which are sometimes different from those held by the authorities. Therefore, it is difficult for the Chinese leadership to get the people to conform to official foreign policy orthodoxy, including the concept of “Peaceful Rise” propagated by the Chinese Communist Party and the government. Emotional outbursts during the anti-American and anti-Japanese protests in 1999 and 2005 respectively reminds us that China’s “Peaceful Rise” has been challenged by the violence and anger of its own people. Key words: Public opinion, foreign policy, China, Peaceful Rise Introduction At the Boao Forum for Asia in China’s Hainan province in November 2003, Zheng Bijian, former vice president of the Central Party School and one of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) leading thinkers and writers on ideological questions, proposed the concept of “Peaceful Rise” by stating that China at the beginning of the 21st century faced two major problems: one concerned multiplication. Multiplied by 1.3 billion, any social or economic problem, no matter how small it is, will become a huge problem. The second one concerned division. Divided by 1.3 billion, China’s resources, no matter how abundant they are, will be at extremely low per capita levels. -

China's Foreign Policy Towards the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Region, 1949-1999

Durham E-Theses China's foreign policy towards the gulf and Arabian Peninsula region, 1949-1999 Binhuwaidin, Mohamed Mousa Mohamed Ali How to cite: Binhuwaidin, Mohamed Mousa Mohamed Ali (2001) China's foreign policy towards the gulf and Arabian Peninsula region, 1949-1999, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4947/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHINA'S FOREIGN POLICY TOWARDS THE GULF AND ARABIAN PENINSULA REGION, 1949-1999 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should i)e published in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. BY MOHAMED MOUSA MOHAMED ALIBINHUWAIDIN A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE FACULITY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM C.M.E.I.S 2001 1'.