Department of Physics United States Naval Academy Lecture 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

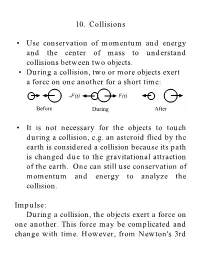

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Impulse and Momentum

Impulse and Momentum All particles with mass experience the effects of impulse and momentum. Momentum and inertia are similar concepts that describe an objects motion, however inertia describes an objects resistance to change in its velocity, and momentum refers to the magnitude and direction of it's motion. Momentum is an important parameter to consider in many situations such as braking in a car or playing a game of billiards. An object can experience both linear momentum and angular momentum. The nature of linear momentum will be explored in this module. This section will discuss momentum and impulse and the interconnection between them. We will explore how energy lost in an impact is accounted for and the relationship of momentum to collisions between two bodies. This section aims to provide a better understanding of the fundamental concept of momentum. Understanding Momentum Any body that is in motion has momentum. A force acting on a body will change its momentum. The momentum of a particle is defined as the product of the mass multiplied by the velocity of the motion. Let the variable represent momentum. ... Eq. (1) The Principle of Momentum Recall Newton's second law of motion. ... Eq. (2) This can be rewritten with accelleration as the derivate of velocity with respect to time. ... Eq. (3) If this is integrated from time to ... Eq. (4) Moving the initial momentum to the other side of the equation yields ... Eq. (5) Here, the integral in the equation is the impulse of the system; it is the force acting on the mass over a period of time to . -

The Physics of a Car Collision by Andrew Zimmerman Jones, Thoughtco.Com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX

The physics of a car collision By Andrew Zimmerman Jones, ThoughtCo.com on 09.10.19 Word Count 947 Level MAX Image 1. A crash test dummy sits inside a Toyota Corolla during the 2017 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. Crash test dummies are used to predict the injuries that a human might sustain in a car crash. Photo by: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images During a car crash, energy is transferred from the vehicle to whatever it hits, be it another vehicle or a stationary object. This transfer of energy, depending on variables that alter states of motion, can cause injuries and damage cars and property. The object that was struck will either absorb the energy thrust upon it or possibly transfer that energy back to the vehicle that struck it. Focusing on the distinction between force and energy can help explain the physics involved. Force: Colliding With A Wall Car crashes are clear examples of how Newton's Laws of Motion work. His first law of motion, also referred to as the law of inertia, asserts that an object in motion will stay in motion unless an external force acts upon it. Conversely, if an object is at rest, it will remain at rest until an unbalanced force acts upon it. Consider a situation in which car A collides with a static, unbreakable wall. The situation begins with car A traveling at a velocity (v) and, upon colliding with the wall, ending with a velocity of 0. The force of this situation is defined by Newton's second law of motion, which uses the equation of This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

The First Law of Thermodynamics for Closed Systems A) the Energy

Chapter 3: The First Law of Thermodynamics for Closed Systems a) The Energy Equation for Closed Systems We consider the First Law of Thermodynamics applied to stationary closed systems as a conservation of energy principle. Thus energy is transferred between the system and the surroundings in the form of heat and work, resulting in a change of internal energy of the system. Internal energy change can be considered as a measure of molecular activity associated with change of phase or temperature of the system and the energy equation is represented as follows: Heat (Q) Energy transferred across the boundary of a system in the form of heat always results from a difference in temperature between the system and its immediate surroundings. We will not consider the mode of heat transfer, whether by conduction, convection or radiation, thus the quantity of heat transferred during any process will either be specified or evaluated as the unknown of the energy equation. By convention, positive heat is that transferred from the surroundings to the system, resulting in an increase in internal energy of the system Work (W) In this course we consider three modes of work transfer across the boundary of a system, as shown in the following diagram: Source URL: http://www.ohio.edu/mechanical/thermo/Intro/Chapt.1_6/Chapter3a.html Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/me103#4.1 Attributed to: Israel Urieli www.saylor.org Page 1 of 7 In this course we are primarily concerned with Boundary Work due to compression or expansion of a system in a piston-cylinder device as shown above. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Chapter 6. Time Evolution in Quantum Mechanics

6. Time Evolution in Quantum Mechanics 6.1 Time-dependent Schrodinger¨ equation 6.1.1 Solutions to the Schr¨odinger equation 6.1.2 Unitary Evolution 6.2 Evolution of wave-packets 6.3 Evolution of operators and expectation values 6.3.1 Heisenberg Equation 6.3.2 Ehrenfest’s theorem 6.4 Fermi’s Golden Rule Until now we used quantum mechanics to predict properties of atoms and nuclei. Since we were interested mostly in the equilibrium states of nuclei and in their energies, we only needed to look at a time-independent description of quantum-mechanical systems. To describe dynamical processes, such as radiation decays, scattering and nuclear reactions, we need to study how quantum mechanical systems evolve in time. 6.1 Time-dependent Schro¨dinger equation When we first introduced quantum mechanics, we saw that the fourth postulate of QM states that: The evolution of a closed system is unitary (reversible). The evolution is given by the time-dependent Schrodinger¨ equation ∂ ψ iI | ) = ψ ∂t H| ) where is the Hamiltonian of the system (the energy operator) and I is the reduced Planck constant (I = h/H2π with h the Planck constant, allowing conversion from energy to frequency units). We will focus mainly on the Schr¨odinger equation to describe the evolution of a quantum-mechanical system. The statement that the evolution of a closed quantum system is unitary is however more general. It means that the state of a system at a later time t is given by ψ(t) = U(t) ψ(0) , where U(t) is a unitary operator. -

12. Elastic Collisions A) Overview B) Elastic Collisions V

12. Elastic Collisions A) Overview In this unit, our focus will be on elastic collisions, namely those collisions in which the only forces that act during the collision are conservative forces. In these collisions, the sum of the kinetic energies of the objects is conserved. We will find that the description of these collisions is significantly simplified in the center of mass frame of the colliding objects. In particular, we will discover that, in this frame, the speed of each object after the collision is the same as its speed before the collision. B) Elastic Collisions In the last unit, we discussed the important topic of momentum conservation. In particular, we found that when the sum of the external forces acting on a system of particles is zero, then the total momentum of the system, defined as the vector sum of the individual momenta, will be conserved. We also determined that the kinetic energy of the system, defined to be the sum of the individual kinetic energies, is not necessarily conserved in collisions. Whether or not this energy is conserved is determined by the details of the forces that the components of the system exert on each other. In the last unit, our focus was on inelastic collisions, those collisions in which the kinetic energy of the system was not conserved. In particular non-conservative work was done by the forces that the individual objects exerted on each other during the collision. In this unit, we will look at examples in which the only forces that act during the collision are conservative forces. -

Collisions in Classical Mechanics in Terms of Mass-Momentum “Vectors” with Galilean Transformations

World Journal of Mechanics, 2020, 10, 154-165 https://www.scirp.org/journal/wjm ISSN Online: 2160-0503 ISSN Print: 2160-049X Collisions in Classical Mechanics in Terms of Mass-Momentum “Vectors” with Galilean Transformations Akihiro Ogura Laboratory of Physics, Nihon University, Matsudo, Japan How to cite this paper: Ogura, A. (2020) Abstract Collisions in Classical Mechanics in Terms of Mass-Momentum “Vectors” with Galilean We present the usefulness of mass-momentum “vectors” to analyze the colli- Transformations. World Journal of Mechan- sion problems in classical mechanics for both one and two dimensions with ics, 10, 154-165. Galilean transformations. The Galilean transformations connect the mass- https://doi.org/10.4236/wjm.2020.1010011 momentum “vectors” in the center-of-mass and the laboratory systems. We Received: August 28, 2020 show that just moving the two systems to and fro, we obtain the final states in Accepted: October 9, 2020 the laboratory systems. This gives a simple way of obtaining them, in contrast Published: October 12, 2020 with the usual way in which we have to solve the simultaneous equations. For Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and one dimensional collision, the coefficient of restitution is introduced in the Scientific Research Publishing Inc. center-of-mass system. This clearly shows the meaning of the coefficient of This work is licensed under the Creative restitution. For two dimensional collisions, we only discuss the elastic colli- Commons Attribution International sion case. We also discuss the case of which the target particle is at rest before License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ the collision. -

AIAA 19Th Fluid Dynamics, Plasma Dynamics and Lasers Conference June 8-10, 1987/Honolulu, Hawaii

AIAA-87 -1407 Electron-Cyclotron-Resonance (ECR) Plasma Acceleration J. C. Sercel Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California AIAA 19th Fluid Dynamics, Plasma Dynamics and Lasers Conference June 8-10, 1987/Honolulu, Hawaii For permission to copy or republish, contact the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1633 Broadway, New York, NY 10019 AIAA-87-1407 ELECTRON-CYCLOTRON-RESONANCE (ECR) PLASMA ACCELERATION Joel C. Sercel* Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California Abstract P power per unit volume, W/m3 R position vector, m A research effort directed at analytically v velocity, mls and experimentally investigating Electron U energy, J or eV Cyclotron-Resonance (ECR) plasma acceleration V electrostatic potential, volts is outlined. Relevant past research is reviewed. T temperature, Kelvin or eV The prospects for application of ECR plasma acceleration to spacecraft propulsion are described. It is shown that previously unexplained losses in converting microwave magnetic dipole moment power to directed kinetic power via ECR plasma reaction cross section, m2 acceleration can be understood in terms of diffusion of energized plasma to the physical time constant, s walls of the accelerator. It is argued that line radiation losses from electron-ion and electron SubscriPts atom inelastic collisions should be less than estimated in past research. Based on this new A acceleration understanding, the expectation now exists that B Bohm efficient ECR plasma accelerators can be e electron designed for application to high specific impulse ex excitation spacecraft propulsion. ionization summation variable refers to lowest energy level Acronyms and Abbreviations p perpendicular r relative D-He3 Deuterium Helium-Three sp space charge induced ECR Electron-Cyclotron-Resonance to t total GE General Electric JPL Jet Propulsion Laboratory LeRC Lewis Research Center I. -

1. Define Open, Closed, Or Isolated Systems. If You Use an Open System As a Calorimeter, What Is the State Function You Can Calculate from the Temperature Change

CH301 Worksheet 13b Answer Key—Internal Energy Lecture 1. Define open, closed, or isolated systems. If you use an open system as a calorimeter, what is the state function you can calculate from the temperature change. If you use a closed system as a calorimeter, what is the state function you can calculate from the temperature? Answer: An open system can exchange both matter and energy with the surroundings. Δ H is measured when an open system is used as a calorimeter. A closed system has a fixed amount of matter, but it can exchange energy with the surroundings. Δ U is measured when a closed system is used as a calorimeter because there is no change in volume and thus no expansion work can be done. An isolated system has no contact with its surroundings. The universe is considered an isolated system but on a less profound scale, your thermos for keeping liquids hot approximates an isolated system. 2. Rank, from greatest to least, the types internal energy found in a chemical system: Answer: The energy that holds the nucleus together is much greater than the energy in chemical bonds (covalent, metallic, network, ionic) which is much greater than IMF (Hydrogen bonding, dipole, London) which depending on temperature are approximate in value to motional energy (vibrational, rotational, translational). 3. Internal energy is a state function. Work and heat (w and q) are not. Explain. Answer: A state function (like U, V, T, S, G) depends only on the current state of the system so if the system is changed from one state to another, the change in a state function is independent of the path. -

Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter After Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

ICARUS 126, 324±335 (1997) ARTICLE NO. IS965655 Carbon Monoxide in Jupiter after Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 1 1 KEITH S. NOLL AND DIANE GILMORE Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 E-mail: [email protected] 1 ROGER F. KNACKE AND MARIA WOMACK Pennsylvania State University, Erie, Pennsylvania 16563 1 CAITLIN A. GRIFFITH Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 AND 1 GLENN ORTON Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California 91109 Received February 5, 1996; revised November 5, 1996 for roughly half the mass. In high-temperature shocks, Observations of the carbon monoxide fundamental vibra- most of the O is converted to CO (Zahnle and MacLow tion±rotation band near 4.7 mm before and after the impacts 1995), making CO one of the more abundant products of of the fragments of Comet Shoemaker±Levy 9 showed no de- a large impact. tectable changes in the R5 and R7 lines, with one possible By contrast, oxygen is a rare element in Jupiter's upper exception. Observations of the G-impact site 21 hr after impact atmosphere. The principal reservoir of oxygen in Jupiter's do not show CO emission, indicating that the heated portions atmosphere is water. The Galileo Probe Mass Spectrome- of the stratosphere had cooled by that time. The large abun- ter found a mixing ratio of H OtoH of X(H O) # 3.7 3 dances of CO detected at the millibar pressure level by millime- 2 2 2 24 P et al. ter wave observations did not extend deeper in Jupiter's atmo- 10 at P 11 bars (Niemann 1996). -

Definitions and Concepts for AQA Physics a Level

Definitions and Concepts for AQA Physics A Level Topic 4: Mechanics and Materials Breaking Stress: The maximum stress that an object can withstand before failure occurs. Brittle: A brittle object will show very little strain before reaching its breaking stress. Centre of Mass: The single point through which all the mass of an object can be said to act. Conservation of Energy: Energy cannot be created or destroyed - it can only be transferred into different forms. Conservation of Momentum: The total momentum of a system before an event, must be equal to the total momentum of the system after the event, assuming no external forces act. Couple: Two equal and opposite parallel forces that act on an object through different lines of action. It has the effect of causing a rotation without translation. Density: The mass per unit volume of a material. Efficiency: The ratio of useful output to total input for a given system. Elastic Behaviour: If a material deforms with elastic behaviour, it will return to its original shape when the deforming forces are removed. The object will not be permanently deformed. Elastic Collision: A collision in which the total kinetic energy of the system before the collision is equal to the total kinetic energy of the system after the collision. Elastic Limit: The force beyond which an object will no longer deform elastically, and instead deform plastically. Beyond the elastic limit, when the deforming forces are removed, the object will not return to its original shape. Elastic Strain Energy: The energy stored in an object when it is stretched.