Donors, Dollars and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third Quarter 2019

MARKET OUTLOOK Q3 2019 MARKET REVIEW AND Q4 2019 OUTLOOK MARKET REPORTS Q3 2019 Macro Recap Economic Activity Marginally Lower GDP Year-on-Year Change (%) Global economic growth remained largely subdued due to trade tensions, 9.0 8.5 8.4 brexit and geopolitical issues. These led to a growing appetite in fixed 8.0 7.4 income securities, pushing debt to negative yields. According to the IMF, 6.8 6.7 global growth is forecast at 3% in 2019, picking up to 3.4% in 2020. 7.0 6 5.4 5.7 Domestically, growth has remained positive. Ghana’s provisional Real Gross 6.0 5 Domestic Product (GDP) in volume terms was estimated to have increased 5.0 4.3 to 5.7% in Q2 2019. When seasonally adjusted, Real GDP was 1.4% in Q2 4.0 2019; down from 1.6% in Q1 2019. The main sub-sectors driving growth in 3.0 the April to June 2019 GDP were Information & Communication, Mining & 2.0 Quarrying, Health & Social Work and Real Estate. 1.0 There was a weakness in economic activity in July 2019. The Composite of 0.0 Economic Activity recorded an annual real decline from 4.3% in July 2018 to 2018_Q2* 2018_Q3* 2018_Q4* 2019_Q1* 2019_Q2* 2.1% in July 2019. The key drivers of economic activity during the period were private sector credit expansion, contributions to SSNIT by the private *Provisional Oil GDP Non-Oil GDP sector, port activity, exports, and domestic VAT. Confidence surveys by the BoG show that on a y-o-y basis, business and 2 consumer confidence declined in Aug-19. -

Has Gse Played Its Role in the Economic Development of Ghana?

CAPITAL MARKET 23 YEARS AND COUNTING: HAS GSE PLAYED ITS ROLE IN THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF GHANA? 1st CAPITAL MARKET CONFERENCE BY EKOW AFEDZIE, DEPUTY MANAGING DIRECTOR MAY 10, 2013 INTRODUCTION Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE) was established with a Vision: -To be a relevant, significant, effective and efficient instrument in mobilizing and allocating long-term capital for Ghana’s economic development and growth. INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES - To facilitate the Mobilization of long term capital by Corporate Bodies/Business and Government through the issuance of securities (shares, bonds, etc). - To provide a Platform for the trading of issued securities. MEMBERSHIP OF GHANA STOCK EXCHANGE GSE as a public company limited by Guarantee has No OWNERS OR SHAREHOLDERS. GSE has Members who are either corporate or individuals. There are two categories of members:- - Licensed Dealing Members - 20 - Associate Members - 34 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1968 - Pearl report by Commonwealth Development Finance Co. Ltd. recommended the establishment of a Stock Exchange in Ghana within two years and suggested ways of achieving it. 1970 – 1989 - Various committees established by different governments to explore ways of bringing into being a Stock Exchange in the country. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1971 - The Stock Exchange Act was enacted. - The Accra Stock Exchange Company incorporated but never operated. Feb, 1989 - PNDC government set up a 10-member National Committee on the establishment of Stock Exchange under the chairmanship of Dr. G.K. Agama, the then Governor of the Bank of Ghana. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND July, 1989 - Ghana Stock Exchange was incorporated as a private company limited by guarantee under the Companies Code, 1963. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Nov. -

2015 Annual Report

Securiries and Exchange Commission 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Securiries and Exchange Commission Vision To be an internationally recognized securities market regulator promoting efficient capital market in Ghana and ensuring investor protection. Mission To promote the orderly growth and development of an efficient, fair and transparent securities market in which investors and the integrity of the market are protected through the proactive implementation of the securities laws. This involves ongoing supervision and regulation of the Ghanaian securities market, education of market operators, policy makers as well as investors on their respective rights and obligations. Objectives • Enhancement of capital market infrastructure and strengthening the capacity of market institutions and intermediaries. • Providing the legal and regulatory framework for market and product innovation. • Promotion of public awareness, investor rights and corporate education • Establishment of an overall robust, supportive, legal and regulatory framework that conforms to international best practices 2 Securiries and Exchange Commission Contents Chairman’s Statement 4 Report of The Director-General 8 Corporate Governance Report 14 Profile of Commissioners 18 Operational Review 24 Broker- Dealers & Advisors Department 32 Funds Management Industry 35 Exchanges and Markets Department 37 Issuers Department 39 Policy, Research and Information Technology Department 45 Legal and Enforcement Department 49 Human Resources & Administration Department 51 Economic Review 53 Capital Market Review 59 Industry Analysis 71 Collective Investment Scheme Sector 75 Financial Statements 78 Commissioners’ Responsibility Statement 79 Independent Auditor’s Report 80 Statement of Operations 82 Statement of Financial Position 83 Statement of Cash Flow 84 Notes to the Financial Statements 85 Register of Licensees 2014/2015 96 Useful contacts 134 3 Securiries and Exchange Commission Chairman’s Statement Introduction as the Centre of capital raising and investment in the sub- region of West-Africa. -

Daily Market Recap

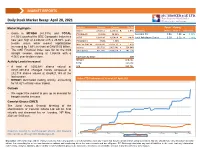

MARKET REPORTS Daily Stock Market Recap: April 28, 2021 Market Highlights Indicator Previous Current Chg (%) Open Closing GSE-CI 2,342.14 2,436.62 4.03% Company Price ¢ Price ¢ Gain/Loss • Gains in MTNGH (+8.33%) and TOTAL YTD (GSE-CI) 20.63% 25.50% Scancom PLC 0.96 1.04 8.33% (+1.56%) pushed the GSE Composite Index to a GSE-FI 1,864.04 1,864.04 0.00% Total Petroleum Ghana 3.20 3.25 1.56% new year high of 2,436.62 with a 25.50% year- YTD (GSE-FI) 4.56% 4.56% to-date return while market capitalization Mkt Cap (GH¢ M) 58,506.48 59,495.31 1.69% increased by 1.69% to close at GH¢59.50 billion. Volume 282,718 1,002,641 254.64% • The GSE Financial Index was flat for the third Value (GH¢) 421,149 1,438,514 241.57% straight session, closing at 1,864.04 with a 4.56% year-to-date return. Top Trades by Value GH¢ MTNGH 840,421 Activity Levels Increased TOTAL 282,019 • A total of 1,002,641 shares valued at GCB 222,741 GH¢1,438,514 changed hands compared to 282,718 shares valued at GH¢421,149 at the last session. Index YTD Performance (%) as at 28th April 2021 • MTNGH dominated trading activity, accounting for 58.42% of total value traded. 30 Outlook 25 • We expect the market to pick up as demand for bargain stocks increase. 20 Camelot Ghana (CMLT) The 22nd Annual General Meeting of the 15 shareholders of Camelot Ghana Ltd will be held virtually and streamed live on Tuesday, 25th May, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. -

Members' Profile

MEMBERS’ PROFILE The Leading Voice of the private sector MEMBERS’ PROFILE The Leading Voice of the private sector Members’ Profile | 3 1 DANPONG HEALTHCARE LTD 67 Nungua Link, Spintex Road, Baatsona, Accra-Ghana COMPANY PROFILE What has grown to become the Danpong Group of Companies started as Danpong Pharmacy (GH) Ltd in September 1989, when Dr. Yaw Adu Gyamfi (Dr. Danpong) formed his initial pharmacy supply company. He launched his first pharmacy shop at Nungua in 1991 with only eight workers, toiling from 7am to 11pm – and often after hours – to build a community pharmacy that was loved by the people of Nungua. In October 1999, Dr Gyamfi expanded his business and set up a bigger pharmacy, a 15-bed clinic, and a modern medical lab at Baatsona, on Spintex Dr. Yaw Adu Gyamfi Road. CEO Through hard work, the sale of quality drugs and high health standards, the Danpong Group became widely known, with loyal customers coming from the nearby community and even further afield, with many referrals from various clinics and hospitals in Ghana. In 2005, Dr Gyamfi also started Danadams Pharmaceuticals Ltd, which focused on manufacturing and selling antiretroviral agents for HIV treatment, and anti-malarial medications. 4 | Members’ Profile Throughout its existence, the Danpong Group has As a company, we are committed to a vision of been committed to promoting good health. In the raising the standard of healthcare in Ghana, where past few years, the company has organized various our services are motivated by quality, affordability, health campaigns and medical screenings for the accessibility, and excellence in all we do. -

WEEKLY MARKET REVIEW 25 June 2018

DATABANK RESEARCH WEEKLY MARKET REVIEW 25 June 2018 ANALYST CERTIFICATE & REQUIRED DISCLOSURE BEGINS ON PAGE 4 GSE MARKET STATISTICS SUMMARY Current Previous % Change Weekly Market Update Databank Stock Index 36,989.82 37,829.75 -2.22% The equities market ended the week with reducing year to date GSE-CI Level 2,918.27 2,989.68 -2.39% returns of 13.12% for the GSE’s Composite Index and 12.49% for Market Cap (GH¢ m) 58,718.96 62,501.44 -6.05% the Databank Stock Index. YTD Return DSI 12.49% 15.04% YTD Return GSE-CI 13.12% 15.89% The gainers this week were ACCESS (+17.65% GH¢4.00), ETI Weekly Volume Traded (Shares) 7,111,051 3,728,037 90.75% (+5.00%, 21Gp) and GOIL (+1.27% GH¢4.00). Weekly Turnover (GH¢) 10,906,829 1,946,907 460.21% The laggards were CAL (-2.40% GH¢1.22), EGH (-11.76% Avg. Daily Volume Traded 878,468 854,409 2.82% (Shares) GH¢9.00), GCB (-0.39% GH¢5.15), SCB (-0.66% GH¢27.15), TLW Avg. Daily Value Traded (GH¢) 3,788,144 3,859,240 -1.84% (-15.00% GH¢14.56), SOGEGH (-17.58%, GH¢1.36) and Total (- No. of Counters Traded 20 20 1.23%, GH¢4.00). No. of Gainers 3 5 A total of ~7.11 million shares valued at ~GH¢10.9 million were No. of Laggards 7 11 traded on the Ghana Stock Exchange this week. Outlook KEY ECONOMIC INDICATORS Fixed Income Market Current Previous Change We anticipate lackluster activity on the Ghana Stock Exchange 91-Day Treasury Bill 13.34% 13.30% +4bps next week with a price gain in Unilever Ghana. -

Weekly Market Watch Sic-Fsl Investment+ Research| Market Reviews|Ghana

WEEKLY MARKET WATCH SIC-FSL INVESTMENT+ RESEARCH| MARKET REVIEWS|GHANA 9th June, 2016 STOCK MARKET GSE TRIMS DOWN LOSSES Activities on the Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE) were more INDICATORS WEEK OPEN WEEK END CHANGE exciting than the previous week’s session, following the superior advantage gainers had over laggards in both Market Capitalization magnitude and numbers last week. Shares of Ecobank (GH¢'million) 54,221.06 54,261.10 0.07% Market Capitalization Ghana Limited (EGH), Cal Bank Limited (CAL), GCB Bank (US$'million) 14,119.52 14,024.22 -0.67% Limited (GCB) and Fan Milk Limited (FML) went up to trim- down the market losses by 0.42% last Thursday. Volume traded (shares) 1,420,412.00 315,034.00 -77.82% Value Traded (GH¢) 1,778,198.31 122,942.09 -93.09% The key benchmark index; GSE Composite Index (GSE CI) flipped up to 1,759.13 points from 1,751.79 points, Value Traded (US$) 463,054.39 31,775.37 -93.14% resulting in an improved year-to-date loss of 11.82%. Table 1: Market Summary Similarly, the GSE Financial Stocks Index (GSE-FSI) and the INDEX ANALYSIS SIC-FSL Top 15 Index (SIC-FSL T-15) also saw 0.52% and 0.30% rise in their respective levels, accounting for their INDICATORS Closing Week YTD improved losses of 14.24% and 18.18% respectively. Level Change CHANGE On the whole, total market capitalization rose slightly by GSE Composite Index 1,759.13 0.42% -11.82% 0.07%, settling at GH¢54.26 billion from the previous SIC-FSL Top 15 Index 3,035.77 0.37% -18.18% week’s figure of GH¢54.22 billion. -

Rankings Rankings

2011 Ghana Club 100 2011 Ghana Club 100 Rankings Rankings Ranking Company Name Weighted 2011 2011 Rank on 2008 2011 Turnover 3-yr. Cpd Rank on 2010 2011 2011 2011 2009 2010 2010 2010 2008 2009 2009 2009 3-yr Avg Rank Rank Turnover (GH¢) Turnover Turnover (GH¢) Growth Growth Owners’ Fund Owners’ Fund Net Profit ROE Owners’ Fund Owners’ Fund Net Profit ROE Owners’ Fund Owners’ Fund Net Profit ROE ROE on ROE (GH¢) Rate (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) (GH¢) Produce Buying Company 1 4.45 1 1,301,776,645.00 2 245,478,455.00 1,301,776,645.00 73.42% 5 23,624,595.00 47,373,503.00 27,654,926.00 77.903% 11,316,143.00 23,624,595.00 14,112,542.00 80.780% 7,353,415.00 11,316,143.00 5,193,545.00 55.637% 0.714 6 Limited rLG Communication 2 12.3 2 52,902,119.00 34 983,433.00 52,902,119.00 272.51% 1 (2,775,216.00) 9,816,767.00 2,592,013.00 73.621% 1,450,420.00 (2,775,216.00) (1,876,798.00) 283.334% 1,305,172.00 1,450,420.00 (714,934.00) -51.890% 1.017 5 Company Limited Enterprise Life Assurance 3 16.3 3 64,658,401.00 31 16,953,510.00 64,658,401.00 55.54% 12 17,385,799.00 25,939,529.00 14,053,730.00 64.875% 10,296,224.00 17,385,799.00 9,589,575.00 69.284% 8,358,476.00 10,296,224.00 2,937,748.00 31.496% 0.552 8 Company Limited 4 Abosso Goldfields Limited 17.25 4 514,614,000.00 5 154,713,000.00 514,614,000.00 48.68% 18 199,099,000.00 338,415,000.00 55.756% 160,258,000.00 199,099,000.00 65,646,000.00 36.535% 102,862,000.00 160,258,000.00 10,924,000.00 8.303% 0.335 27 149,849,000.00 Ghana Home Loans 5 22.75 5 11,650,113.00 63 2,506,610.00 11,650,113.00 -

Report of the Directors to the Members of Camelot Ghana Limited for the Year Ended 31 December 2018

CONTENTS Notice Of Annual General Meeting 01 02 Board of Directors 03 Chairmans Statement 06 Report of Directors 07 Independent Auditors Report 09 Consolidated Statement Of Comprehensive Income 12 Consolidated Statement Of Changes In Equity 13 Consolidated Statement Of Financial Position 15 Consolidated Statement Of Cash Flow 16 Extracts Notes To The Consolidated Financial Statements 17 Notes To The Co nso lidated Financial Statements 26 Five Year Financial Summary 41 Shareholding Structure 42 Proxy Form 43 2018 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING BOOKLET NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the 20th Annual General Meeting of CAMELOT GHANA LIMITED will be held in the King of Kings Hall of Christ the King Parish (opposite Jubilee House), on Wednesday 29th May 2019 at 10 am prompt. AGENDA 1. To receive and adopt the Financial Statements of the Company for the period ended 31st December 2018 together with the reports of the Directors and Auditors thereon. 2. To re-elect Directors retiring by rotation. 3. To fix the remuneration of Directors. 4. To authorise the Directors to fix the remuneration of the Auditors. DATED THIS 27th DAY OF MARCH 2019 BY ORDER OF THE BOARD R.B. CONSULT SECRETARY NOTE: A member of the Company entitled to attend and vote is entitled to appoint a proxy to attend and vote instead of him/her. A proxy need not be a member of the Company. A form of proxy must be completed and deposited at the office of the Registrars, Universal Merchant Bank, Registrar’s Department, Adabraka Branch, next to Adabraka Police Station, P.O. -

2019 – Quarter 3

ENSURING INVESTOR PROTECTION SEC OFFICIALNEWS NEWSLETTER OF SECURITIES & EXCHANGE COMMISSION 3RD QUARTER (JUL. - SEPT.) 2019 Growth and Emerging Markets Committee Revocation of Licenses of Fund Management Companies Highlights Of The Growth & Emerging Markets Committee And Public Conference 3rd Quarter Market Summary Analysis & Highlights Key Market Statistics Infractions, Penalties and Complaints Received in the Third Quarter of 2019. “Spend each day trying to be a little wiser than you were when you woke up ” - Charlie Munger SECURITIES & EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC NEWS 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 NOTICE TO THE PUBLIC Public Advice Public Notice 31 INTERNATIONAL UPDATES The Growth and Emerging Markets Committee and Public Conference was held in St. Petersburg, Russia on 19th and 20th September 2019. 33 KNOWLEDGE BANK In this edition which is the concluding part of the series on Collective Investment Schemes, we take a recap of, what is a mutual fund and unit trust. 35 ENFORCEMENTS Infractions, Penalties and Complaints Received during the Second Quarter of 2019 37 FACTS & FIGURES - Assets under Management (3rd Quarter 2019) - Offers and Other Approvals - Capital Market Statistics and Analysis 40 MARKET SUMMARY ANALYSIS & HIGHLIGHTS At the end of third quarter (Q3) 2019, the Ghana Stock Exchange Composite index, the GSE-CI closed at 2,204.79 points from 2,394.82 points recorded at the end of second quarter 2019. This represents a -14.28% year-to-date (YTD) change compared to -6.90% YTD as at the end of second quarter (Q2) 2019 EDITORIAL TEAM 1. Dr Jacob Aidoo 5. Mrs Naomi Simpson 2. Mr Emmanuel Ashong-Katai 6. -

Members' Profile

MEMBERS’ PROFILE The Leading Voice of the private sector MEMBERS’ PROFILE The Leading Voice of the private sector Members’ Profile | 3 1 DANPONG HEALTHCARE LTD 67 Nungua Link, Spintex Road, Baatsona, Accra-Ghana COMPANY PROFILE What has grown to become the Danpong Group of Companies started as Danpong Pharmacy (GH) Ltd in September 1989, when Dr. Yaw Adu Gyamfi (Dr. Danpong) formed his initial pharmacy supply company. He launched his first pharmacy shop at Nungua in 1991 with only eight workers, toiling from 7am to 11pm – and often after hours – to build a community pharmacy that was loved by the people of Nungua. In October 1999, Dr Gyamfi expanded his business and set up a bigger pharmacy, a 15-bed clinic, and a modern medical lab at Baatsona, on Spintex Dr. Yaw Adu Gyamfi Road. CEO Through hard work, the sale of quality drugs and high health standards, the Danpong Group became widely known, with loyal customers coming from the nearby community and even further afield, with many referrals from various clinics and hospitals in Ghana. In 2005, Dr Gyamfi also started Danadams Pharmaceuticals Ltd, which focused on manufacturing and selling antiretroviral agents for HIV treatment, and anti-malarial medications. 4 | Members’ Profile Throughout its existence, the Danpong Group has As a company, we are committed to a vision of been committed to promoting good health. In the raising the standard of healthcare in Ghana, where past few years, the company has organized various our services are motivated by quality, affordability, health campaigns and medical screenings for the accessibility, and excellence in all we do. -

List of Companies in Ghana Club 100 - 2016 (Awarded in 2017)

LIST OF COMPANIES IN GHANA CLUB 100 - 2016 (AWARDED IN 2017) 1. Newmont Golden Ridge Limited 2. Scancom Limited (MTN Ghana) 3. Ghana Oil Company Limited (GOIL) 4. Gold Fields Ghana Limited 5. Vivo Energy Ghana Limited 6. Unibank Ghana Limited 7. Multipro Private Limited 8. Nordea Capital Limited 9. Justmoh Construction Limited 10. Total Petroleum Ghana Limited 11. Newmont Ghana Gold Limited 12. Ecobank Ghana Limited 13. McOttley Capital Limited 14. Barclays Bank Ghana Limited 15. Fan Milk Ghana Limited 16. Glico Healthcare Limited 17. Asa Savings and Loans Limited 18. Fidelity Bank Ghana Limited 19. Toyota Ghana Company Limited 20. Ghana Community Network Services Limited 21. Enterprise Life Assurance Company Limited 22. Unilever Ghana Limited 23. DHL Ghana Limited 24. Enterprise Trustees Limited 25. Zenith Bank Ghana Limited 26. Certification, Inspection and Training Limited 27. Sefwiman Rural Bank Limited Downloaded from websiteghana.com 28. Fiaseman Rural Bank Limited 29. Stanbic Bank Ghana Limited 30. Amenfiman Ghana Limited 31. Dalex Finance Company Limited 32. Atwima Kwanwoma Rural Bank Limited 33. Guaranty Trust Bank Ghana Limited 34. Melcom Ghana Limited 35. Otuasekan Rural Bank Limited 36. McDan Shipping Company Limited 37. South Akim Rural Bank Limited 38. DCI Microfinance Limited 39. SIC Life Company Limited 40. Ghana Home Loans 41. First Atlantic Bank Limited 42. Enterprise Life Insurance Company Limited 43. Tropical Cable and Conductor Limited 44. uniCredit Ghana Limited 45. Societe Generale Ghana Limited 46. Bond Savings and Loans Limited 47. Star Assurance Company Limited 48. B 5 Plus Limited 49. Ahantaman Rural Bank Limited 50. Akim Bosome Rural Bank Limited 51.