Persian Cluster Forecast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Mohammad Hossein Kowsari

Curriculum Vitae Mohammad Hossein Kowsari Name : Mohammad Hossein Kowsari Place and Date of Birth : Eqlid County, Fars Province, Iran, June 6, 1978. Address : Department of Chemistry, and Center for Research in Climate Change and Global Warming (CRCC), Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences (IASBS) Zanjan, 45137-66731, Iran E-mail : [email protected] and [email protected] Cell: 98-09131295598 Tel.: 98-24-33153207 Fax: 98-24-33153232 M. H. Kowsari Google Scholar: Citations: 545, h-index: 11, i10-index: 12 (25 April 2021) Research group homepage: https://iasbs.ac.ir/~mhkowsari/index.html . Professional Experience Position Location Dates 1. Associate Professor Department of Chemistry, Jan 2018 - Continuous IASBS, Zanjan, Iran 2. Assistant Professor * Department of Chemistry, Feb 2011- Jan 2018 IASBS, Zanjan, Iran 3. Postdoctoral fellow Department of Chemistry, Oct 2010 – Feb 2011 IASBS, Zanjan, Iran 4. Postdoctoral fellow Supercomputing Center, Isfahan University of Technology, Oct 2009 – Oct 2010 Isfahan, Iran (Prof. M. Ashrafizaadeh) * Director of the Education Office of IASBS, Nov. 2013 – Nov. 2015. Education Degree Location (Advisor) Dates Ph.D. Department of Chemistry, Sept 2004 – Oct 2009 (Physical Chemistry) Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan, Iran (Prof. Saman Alavi, University of Ottawa, Canada ) (Prof. Bijan Najafi, Isfahan University of Technology ) M.Sc. Department of Chemistry, Sept 2000 – June 2002 (Physical Chemistry) Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan, Iran (Prof. Bijan Najafi) B.Sc. Department of Chemistry, Sept 1996 – June 2000 (Pure Chemistry) Isfahan University, Isfahan, Iran 1 Ph.D. Thesis Title “Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids: Determine of the Dynamics and Transport Properties, Structure and Melting Point” 2009. -

Controversy Over Coseismic Surface Faulting in the Zagros Orogenic Belt of Iran: Evidence from Geological Field

World Journal of Environmental Biosciences All Rights Reserved WJES © 2014 Available Online at: www.environmentaljournals.org Volume 6, Supplementary: 63-70 ISSN 2277- 8047 Controversy Over Coseismic Surface Faulting in The Zagros Orogenic Belt of Iran: Evidence from Geological Field Alireza Sepasdar1, Ahmad Zamani2*, Kouros Yazdjerdi2, Mohsen Poorkermani3, M. Ghorashi4 1Department of geology, Fars Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Fars, Iran 2-Department of geology, Shiraz branch, Islamic Azad university, Shiraz, Iran. 3-Department of geology, North Tehran branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. 4Geological survey of Iran, Po13185-1494, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT In this research, it was attempted to examine the impact of tectonic activities on Surmehmountain to create the rupture. Surmeh anticline is the most important geological feature of the southwest Zagros orogeny belt in Fars province, Iran. The structure of the rock of Paleozoic- Mesozoic age is complex. Several levels of deformation are probably recognized in the Alpian orogeny. The Alpian Orogeny produced folds, low angle thrust, numerous normal faults, a moderate graben and widespread fracture zones. The trend of most faults, folds and fracture zones is from northwest to southeast. In this county, the main fault is Surmeh thrust. Due to these effects, Dalan formation contains some clay minerals, Marl perch on Dalan formation and beneath it, perch Foraghan formation and Hurmoz series. At the following tectonic phase, the region creates an appropriate condition for salt diapirism, therefore, in the north county, two salt domes can be seen which are called Jahani dome. Although, the Earth scientists believe that in the southwest of Zagros organic belt, the surficial rupture cannot be seen. -

The Erosion Yield Potention of Lithology Unite in Komroud Drainage Basin (North Semnan, Iran) Using MPSIAC Method

2012 International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology IPCBEE vol.30 (2012) © (2012) IACSIT Press, Singapore The Erosion Yield Potention of Lithology Unite in Komroud Drainage Basin (North Semnan, Iran) Using MPSIAC Method + Ahmad Adib1 , Davood Jahani2, Masomeh Zareh 3 1Faculty of Engineering, Islamic Azad University, South Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran 2, 3 Geology department, Islamic Azad University, North Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran Abstract. Komroud basin with area of 32 km2 is located at North of Semnan Provence. Kahar formation with the age of infracamberian is the oldest available stones in this basin. Stone units in infracamberian and Cambrian formation cover more than 50% area of total range. This region is generally consisting of sediment stones. 6 main factors including geology, climate, tectonic, slope, plant cover and weathering are influence on level of erosion of rock units. In this research effective factors on erosion will be studied. And by using Arc GIS software the level of sediment yield map and investigation of formations to erosion at Komroud basin was specified. Most important factors on erosion at this region include geology, tectonic and slope. Then based on MPSIAC the related tables, maps will be prepared and finally the level of sediment at Komroud basin will be achieved. Results of tests and studies, certified that stone units of Komroud basin are classified within 5 erosion groups in which Quaternary unite had very high erosion and Lalun & Mila formation had very low sediment. Factors including Surface geology were effective on Komroud basin. Keywords: Komroud Drainage Basin, Erosion, Alluvium, Erosion Sensitive 1. Introduction Sedimentation measure can be estimated by different methods. -

The Location Optimization of Wind Turbine Sites with Using the MCDM Approach: a Case Study

Energy Equip. Sys./ Vol. 5/No.2/ June 2017/165-187 Energy Equipment and Systems http://energyequipsys.ut.ac.ir www.energyequipsys.com The location optimization of wind turbine sites with using the MCDM approach: A case study Author ABSTRACT a* Mostafa Rezaei-Shouroki The many advantages of renewable energies—especially wind—such as abundance, permanence, and lack of pollution, have encouraged a Industrial Engineering Department, many industrialized and developing countries to focus more on these Yazd University, Yazd, Iran clean sources of energy. The purpose of this study is to prioritize and rank 13 cities of the Fars province in Iran in terms of their suitability for the construction of a wind farm. Six important criteria are used to prioritize and rank these cities. Among these, wind power density— the most important criterion—was calculated by obtaining the three- hourly wind speed data at the height of 10 m above ground level related to the time period between 2004 and 2013 and then extrapolating these data to acquire wind speed related to the height of 40 m. The Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method was used for prioritizing and ranking the cities, after which Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Fuzzy Technique for Order of Preference by Article history: Similarity to Ideal Solution (FTOPSIS) methods were used to assess the validity of the results. According to the results obtained from these Received : 20 September 2016 three methods, the city of Izadkhast is recommended as the best Accepted : 5 February 2017 location for the construction of a wind farm. Keywords: Wind Farm; Prioritizing; Optimization; Fars Province; Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). -

MASTER's THESIS Tourism Attractions and Their Influence On

2009:057 MASTER'S THESIS Tourism Attractions and their Influence on Handicraft Employment in Isfahan Reza Abyareh Luleå University of Technology Master Thesis, Continuation Courses Marketing and e-commerce Department of Business Administration and Social Sciences Division of Industrial marketing and e-commerce 2009:057 - ISSN: 1653-0187 - ISRN: LTU-PB-EX--09/057--SE 1 Master Thesis Tourism Attractions and their Influence on Handicraft Employment in Isfahan Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Peter U.C.Dieke and Prof.Dr.Ali Sanayei By: Reza Abyareh Fall 2007 2 Master Thesis Tourism and Hotel Management Lulea University of Technology (Sweden) and University of Isfahan(Iran) Tourism Attractions and their Influence on Handicraft Employment in Isfahan Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Peter U.C.Dieke and Prof.Dr.Ali Sanayei By: Reza Abyareh A Master Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Master of Tourism and Hotel Management in Lulea University of Technology. Fall 2007 3 In The Name of God ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dedicated to My parents and my sister,the most important three persons in my life. 4 Contents ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Acknowledgements 1 Overview 7 Introduction 7 Key Words 8 Description of Research Problem 9 Importance and Value of Research 10 Record and History of Research Subject 11 Purposes of Research 12 Research Questions 12 Sample size 13 Research Method 13 Tools for Collecting Data 13 Data Collection and Analysis -

And “Climate”. Qarah Dagh in Khorasan Ostan on the East of Iran 1

IRAN STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 1397 1. LAND AND CLIMATE Introduction T he statistical information that appeared in this of Tehran and south of Mazandaran and Gilan chapter includes “geographical characteristics and Ostans, Ala Dagh, Binalud, Hezar Masjed and administrative divisions” ,and “climate”. Qarah Dagh in Khorasan Ostan on the east of Iran 1. Geographical characteristics and aministrative and joins Hindu Kush mountains in Afghanistan. divisions The mountain ranges in the west, which have Iran comprises a land area of over 1.6 million extended from Ararat mountain to the north west square kilometers. It lies down on the southern half and the south east of the country, cover Sari Dash, of the northern temperate zone, between latitudes Chehel Cheshmeh, Panjeh Ali, Alvand, Bakhtiyari 25º 04' and 39º 46' north, and longitudes 44º 02' and mountains, Pish Kuh, Posht Kuh, Oshtoran Kuh and 63º 19' east. The land’s average height is over 1200 Zard Kuh which totally form Zagros ranges. The meters above seas level. The lowest place, located highest peak of this range is “Dena” with a 4409 m in Chaleh-ye-Loot, is only 56 meters high, while the height. highest point, Damavand peak in Alborz The southern mountain range stretches from Mountains, rises as high as 5610 meters. The land Khouzestan Ostan to Sistan & Baluchestan Ostan height at the southern coastal strip of the Caspian and joins Soleyman Mountains in Pakistan. The Sea is 28 meters lower than the open seas. mountain range includes Sepidar, Meymand, Iran is bounded by Turkmenistan, the Caspian Sea, Bashagard and Bam Posht Mountains. -

A New Perspective on the Status of the Intestinal Parasitic Infections in the Rural Areas of Fars Province South of Iran

Archive of SID Iran J Public Health, Vol. 48, No.8, Aug 2019, pp.1518-1522 Short Communication A New Perspective on the Status of the Intestinal Parasitic Infections in the Rural Areas of Fars Province South of Iran Mojtaba NOWROZI 1, Gholam Reza MOWLAVI 2, Mostafa ALISHAVANDI 1, *Gholamreza HATAM 3 1. Department of Parasitology and Mycology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran 2. Department of Parasitology and Mycology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 3. Basic Sciences in Infectious Diseases Research Center, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] (Received 24 Mar 2018; accepted 19 May 2018) Abstract Background: Parasitoses are among the most important problems of most countries especially developing countries. We aimed to detect the situation of intestinal parasitic infections in the Farashband district in Fars Province South of Iran and identify influential factors in the escalation of parasitic diseases and to reduce them. Methods: Overall, 1009 participants from the age of 6 months to 90 years were selected from 3 cities and 15 villages of Farashband district, Fars Province South of Iran from 2015 to 2016. Parasitological methods such as the direct assay method, formalin-ether concentration method, and zinc sulfate flotation were used for diagnosis of worm eggs, cysts, and protozoa trophozoite. Susceptible and protozoan positive samples were stained using the Trichrome stain- ing method. The modified acid-fast staining procedure was conducted for diarrheal samples and the results were used for diagnosis of coccidia. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Geotourism Attractions in the Bare Nature of Yazd Province

ADVANCES IN BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH Geotourism Attractions in the Bare Nature of Yazd Province KAMAL OMIDVAR1, YOUNES KHOSRAVI2 1Department of Geography 2Department of Geography 1 Yazd University 2 Yazd University 1Address: Faculty of Human Science, Yazd University, Yazd Iran 2Address: Faculty of Human Science, Yazd University, Yazd Iran 1E-mail: [email protected] 2E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Climatic conditions governing over Yazd province have caused a situation in which the most areas covered by bare and barren lands. Relief in this province is rooted in the ancient geology history of Iran and the world. From the most ancient structures of the geology in the world (Precambrian) to the newest ones (Holocene) are seen at a distance which is less than 100 km in this province. We can rarely see very various ecotourism attractions such as deserts, salt playas, sand dunes, Qantas, glacial circuses, spring, karstic caves and kalouts in the other areas of the world in a small distance away from each other. Therefore this province can have special status in ecotourism industry because of its attractions and developing this industry will result in socio-economic advancement and an increase in the employment rate in Yazd province.This research attempts to consider ecotourism attractions briefly in Yazd province and introduce available potential abilities in this field. Key-Words: Ecotourism, Sand Dune, Playa, Qanat, Desert, Glacial Circus, Kalout, Yazd Province. 1 Introduction conducted studies on the shapes and relief of the Climatic variety not only in current age, but also in earth in Yazd province confirm the presence of various climatic periods has been very diverse in fossils from Precambrian period (approximate age is Yazd province area. -

ID 449 Location Optimization of Hybrid Solar- Wind Plants by Using

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Bandung, Indonesia, March 6-8, 2018 Location optimization of hybrid solar- wind plants by using FTOPSIS method Mostafa Rezaei Industrial Engineering Department Yazd University Yazd, Iran [email protected] Mojtaba Qolipour Industrial Engineering Department Yazd University Yazd, Iran [email protected] Hengame Hadian Industrial Engineering Department Nahavand University Nahavand, Iran Amir-Mohammad Golmohammadi Industrial Engineering Department Yazd University Yazd, Iran [email protected] Abstract Nowadays depletion of fossil fuel resources and air pollution are the two most concerning issues that human is facing with because of increasing demands and consumption. These reasons make renewable and green energies such as wind and solar an attractive source of energy in world. The current study is an investigation research to estimate wind and solar energy potential in different cities of Fars province in Iran. Afterward is attempted to prioritize the places for hybrid solar-wind constructions. For this purpose 4 main criteria including economic condition, social condition, geological condition and natural disasters which each criterion has sub-criteria were investigated. Wind power density and solar irradiation are the most important criteria and are estimated by the Weibull distribution function and Angstrom-Prescott equation, respectively. After calculating the amount of wind and solar energy by using long-term 3-hourly data, results showed that Eghlid and Estahban have the highest amount of wind power and solar energy, respectively. FTOPSIS is used for ranking the cities and AHP, ELECTREE III, WSM, MAPPAC and DEA are applied to validate the results. According to results, the best city for establishing hybrid wind- solar site is Eghlid. -

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト ● Asia 4 Bangladesh 7 China アジア バングラデシュ 中国 1 Afghanistan 9 Khulna 6 Hangzhou アフガニスタン クルナ 杭州(ハンチォウ) 1 Herat 10 Kotwalipara 7 Wuhan ヘラート コタリパラ 武漢(ウハン) 2 Kabul 11 Meherpur 8 Cyprus カブール メヘルプール キプロス 3 Nili 12 Moulvibazar 1 Aglantzia ニリ モウロビバザール アグランツィア 2 Armenia 13 Narayanganj 2 Ammochostos (Famagusta) アルメニア ナラヤンガンジ アモコストス(ファマグスタ) 1 Yerevan 14 Narsingdi 3 Kyrenia エレバン ナールシンジ キレニア 3 Azerbaijan 15 Noapara 4 Kythrea アゼルバイジャン ノアパラ キシレア 1 Agdam 16 Patuakhali 5 Morphou アグダム(県) パトゥアカリ モルフー 2 Fuzuli 17 Rajshahi 9 Georgia フュズリ(県) ラージシャヒ ジョージア 3 Gubadli 18 Rangpur 1 Kutaisi クバドリ(県) ラングプール クタイシ 4 Jabrail Region 19 Swarupkati 2 Tbilisi ジャブライル(県) サルプカティ トビリシ 5 Kalbajar 20 Sylhet 10 India カルバジャル(県) シルヘット インド 6 Khocali 21 Tangail 1 Ahmedabad ホジャリ(県) タンガイル アーメダバード 7 Khojavend 22 Tongi 2 Bhopal ホジャヴェンド(県) トンギ ボパール 8 Lachin 5 Bhutan 3 Chandernagore ラチン(県) ブータン チャンダルナゴール 9 Shusha Region 1 Thimphu 4 Chandigarh シュシャ(県) ティンプー チャンディーガル 10 Zangilan Region 6 Cambodia 5 Chennai ザンギラン(県) カンボジア チェンナイ 4 Bangladesh 1 Ba Phnom 6 Cochin バングラデシュ バプノム コーチ(コーチン) 1 Bera 2 Phnom Penh 7 Delhi ベラ プノンペン デリー 2 Chapai Nawabganj 3 Siem Reap Province 8 Imphal チャパイ・ナワブガンジ シェムリアップ州 インパール 3 Chittagong 7 China 9 Kolkata チッタゴン 中国 コルカタ 4 Comilla 1 Beijing 10 Lucknow コミラ 北京(ペイチン) ラクノウ 5 Cox's Bazar 2 Chengdu 11 Mallappuzhassery コックスバザール 成都(チォントゥ) マラパザーサリー 6 Dhaka 3 Chongqing 12 Meerut ダッカ 重慶(チョンチン) メーラト 7 Gazipur 4 Dalian 13 Mumbai (Bombay) ガジプール 大連(タァリィェン) ムンバイ(旧ボンベイ) 8 Gopalpur 5 Fuzhou 14 Nagpur ゴパルプール 福州(フゥチォウ) ナーグプル 1/108 Pages -

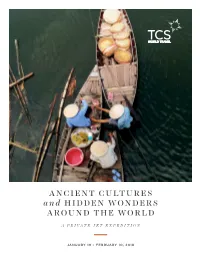

ANCIENT CULTURES and HIDDEN WONDERS AROUND the WORLD

ANCIENT CULTURES and HIDDEN WONDERS AROUND THE WORLD A PRIVATE JET EXPEDITION JANUARY 19 – FEBRUARY 10, 2018 COLLECT A LIFETIME OF MOMENTS IN A SINGLE JOURNEY. Moments you will continue to live—long after the trinkets have been recycled, the photographs faded and the pages cracked and torn. The journey in these pages is made for explorers who understand travel’s real value, for those who never settle for second best—for you. COVER: Vietnamese women in their boat, Hôi An, Vietnam THIS PAGE: Masjed-e Jame, Isfahan, Iran SEATTLE | Begin CASABLANCA, ISFAHAN, MOROCCO IRAN KYOTO, ORLANDO | End JAPAN CAIRO AND LUXOR, EGYPT HÔI AN, VIETNAM GUAYAQUIL AND GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS, ECUADOR RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL ANCIENT CULTURES and HIDDEN WONDERS AROUND THE WORLD A PRIVATE JET EXPEDITION Discover eight legendary destinations—including 10 UNESCO World Heritage sites—that have captured the imaginations of humankind on one seamless, all-inclusive journey. 23 DAYS | 52 GUESTS | ALL-INCLUSIVE January 19 – February 10, 2018 $108,950 per person, double occupancy $11,950 single supplement To reserve your space, visit TCSWorldTravel.com, call 800.454.4149 or email [email protected] “GREAT DESTINATIONS, INCREDIBLE ATTENTION TO DETAIL AND THE MOST PERSONALIZED TRAVEL COMPANY I KNOW.” - KIT SHAW TCS WORLD TRAVEL GUEST FOR MORE THAN 20 YEARS, TCS WORLD TRAVEL HAS TURNED TRAVEL DREAMS INTO BREATHTAKING REALITY. TCS World Travel is the world leader in private jet expeditions. Our all-inclusive, globe-circling journeys are meticulously orchestrated, linking unique cultures, historic sites and natural wonders rarely experienced together. Our customized Boeing 757 delivers a seamless in-flight experience, flying direct without airport layovers to most destinations, including remote places hard to reach by commercial air.