Weaponizing Kleptocracy: Putin's Hybrid Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kremlin Trojan Horses | the Atlantic Council

Atlantic Council DINU PATRICIU EURASIA CENTER THE KREMLIN’S TROJAN HORSES Alina Polyakova, Marlene Laruelle, Stefan Meister, and Neil Barnett Foreword by Radosław Sikorski THE KREMLIN’S TROJAN HORSES Russian Influence in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom Alina Polyakova, Marlene Laruelle, Stefan Meister, and Neil Barnett Foreword by Radosław Sikorski ISBN: 978-1-61977-518-3. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. November 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Foreword Introduction: The Kremlin’s Toolkit of Influence 3 in Europe 7 France: Mainstreaming Russian Influence 13 Germany: Interdependence as Vulnerability 20 United Kingdom: Vulnerable but Resistant Policy recommendations: Resisting Russia’s 27 Efforts to Influence, Infiltrate, and Inculcate 29 About the Authors THE KREMLIN’S TROJAN HORSES FOREWORD In 2014, Russia seized Crimea through military force. With this act, the Kremlin redrew the political map of Europe and upended the rules of the acknowledged international order. Despite the threat Russia’s revanchist policies pose to European stability and established international law, some European politicians, experts, and civic groups have expressed support for—or sympathy with—the Kremlin’s actions. These allies represent a diverse network of political influence reaching deep into Europe’s core. The Kremlin uses these Trojan horses to destabilize European politics so efficiently, that even Russia’s limited might could become a decisive factor in matters of European and international security. -

Populism and Corruption

Transparency International Anti-Corruption Helpdesk Answer Populism and corruption Author(s): Niklas Kossow, [email protected] Reviewer(s): Roberto Martínez B. Kukutschka, [email protected] Date: 14 January 2019 This Helpdesk Answer looks at how corruption and populism interlink. First, it provides an overview of the different definitions of populism, all of which point to the fact that populism, as a political ideology and as a style of political communication, divides society into two groups: the people and the “elites”. Second, it explains how corruption becomes an inherent part of populist rhetoric and policies: populist leaders stress the message that the elites works against the interest of the people and denounce corruption in government in order to stylize themselves as outsiders and the only true representatives of the people’s interest. While the denunciations of corruption can often be considered valid, populist leaders rather than effectively fighting corruption use the populist rhetoric as a smoke screen to redistribute the spoils of corruption amongst their allies. In many cases populism even facilitate new forms of corruption. Finally, the answer uses examples from Hungary, the Philippines and the USA to show how corruption and populism relate to one another. © 2019 Transparency International. All rights reserved. This document should not be considered as representative of the Commission or Transparency International’s official position. Neither the European Commission,Transparency International nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. This Anti-Corruption Helpdesk is operated by Transparency International and funded by the European Union. -

Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence Of

Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Elections are essential elements of democratic systems. Unfortunately, abuse and manipulation (including voter intimidation, vote buying or ballot stuffing) can distort these processes. However, little attention has been paid to an intrinsic part of this threat: the conditions and opportunities for criminal interference in the electoral process. Most worrying, few scholars have examined the underlying conditions that make elections vulnerable to organized criminal involvement. This report addresses these gaps in knowledge by analysing the vulnerabilities of electoral processes to illicit interference (above all by organized crime). It suggests how national and international authorities might better protect these crucial and coveted elements of the democratic process. Case studies from Georgia, Mali and Mexico illustrate these challenges and provide insights into potential ways to prevent and mitigate the effects of organized crime on elections. International IDEA Clingendael Institute ISBN 978-91-7671-069-2 Strömsborg P.O. Box 93080 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2509 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 8 698 37 00 T +31 70 324 53 84 F +46 8 20 24 22 F +31 70 328 20 02 9 789176 710692 > [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.clingendael.nl ISBN: 978-91-7671-069-2 Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Series editor: Catalina Uribe Burcher Lead authors: Ivan Briscoe and Diana Goff © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2016 Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute) International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Europe's Two-Faced Authoritarian Right FINAL.Pdf

1 Europe’s two-faced authoritarian right: ‘anti-elite’ parties serving big business interests 15 May 2019 INTRODUCTION If the more pessimistic projections are to be believed, authoritarian right-wing politicians will do well in the upcoming European Parliament elections, reflecting a surge in EU scepticism and disillusionment with establishment parties, many of whom have overseen a decade or more of punishing austerity. These authoritarian right parties are harnessing this disillusionment using the rhetoric of ending corruption, tackling ‘elite’ interests, regaining ‘national’ dignity and identity, and defending the rights of ‘ordinary people’. However, the contrast between this rhetoric and their actual actions is stark. From repressive laws to dark money funding; from corruption scandals to personal enrichment; from corporate deregulation to enabling tax avoidance, the defence of ‘elite’ interests disguised as the defence of disaffected classes is a defining characteristic of Europe’s rising authoritarian right parties. After the election, Europe could well see the formation of a new axis by these parties across the EU institutions, simultaneously becoming a significant force in the European Parliament, while having a strong voice in the Council and European Council, and nominating like-minded commissioners to the EU’s executive. Such an alliance could undermine or prevent action to tackle some of the most pressing issues facing us such as climate change, whilst working against workers’ rights, and measures to regulate and tax business -

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations May 21, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45733 SUMMARY R45733 Combating Corruption in Latin America May 21, 2019 Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from June S. Beittel, office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency Coordinator International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of Analyst in Latin American respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several Affairs analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize Peter J. Meyer citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative Specialist in Latin investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater American Affairs affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean Clare Ribando Seelke countries. Specialist in Latin American Affairs Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter Maureen Taft-Morales discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of Specialist in Latin official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized American Affairs crime and criminal impunity. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

Treisman Silovarchs 9 10 06

Putin’s Silovarchs Daniel Treisman October 2006, Forthcoming in Orbis, Winter 2007 In the late 1990s, many Russians believed their government had been captured by a small group of business magnates known as “the oligarchs”. The most flamboyant, Boris Berezovsky, claimed in 1996 that seven bankers controlled fifty percent of the Russian economy. Having acquired massive oil and metals enterprises in rigged privatizations, these tycoons exploited Yeltsin’s ill-health to meddle in politics and lobby their interests. Two served briefly in government. Another, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, summed up the conventional wisdom of the time in a 1997 interview: “Politics is the most lucrative field of business in Russia. And it will be that way forever.”1 A decade later, most of the original oligarchs have been tripping over each other in their haste to leave the political stage, jettisoning properties as they go. From exile in London, Berezovsky announced in February he was liquidating his last Russian assets. A 1 Quoted in Andrei Piontkovsky, “Modern-Day Rasputin,” The Moscow Times, 12 November, 1997. fellow media magnate, Vladimir Gusinsky, long ago surrendered his television station to the state-controlled gas company Gazprom and now divides his time between Israel and the US. Khodorkovsky is in a Siberian jail, serving an eight-year sentence for fraud and tax evasion. Roman Abramovich, Berezovsky’s former partner, spends much of his time in London, where he bought the Chelsea soccer club in 2003. Rather than exile him to Siberia, the Kremlin merely insists he serve as governor of the depressed Arctic outpost of Chukotka—a sign Russia’s leaders have a sense of humor, albeit of a dark kind. -

Russia's Silence Factory

Russia’s Silence Factory: The Kremlin’s Crackdown on Free Speech and Democracy in the Run-up to the 2021 Parliamentary Elections August 2021 Contact information: International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) Rue Belliard 205, 1040 Brussels, Belgium [email protected] Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 II. INTRODUCTION 6 A. AUTHORS 6 B. OBJECTIVES 6 C. SOURCES OF INFORMATION AND METHODOLOGY 6 III. THE KREMLIN’S CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 7 A. THE LEGAL TOOLKIT USED BY THE KREMLIN 7 B. 2021 TIMELINE OF THE CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 9 C. KEY TARGETS IN THE CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 12 i) Alexei Navalny 12 ii) Organisations and Individuals associated with Alexei Navalny 13 iii) Human Rights Lawyers 20 iv) Independent Media 22 v) Opposition politicians and pro-democracy activists 24 IV. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS TRIGGERED BY THE CRACKDOWN 27 A. FREEDOMS OF ASSOCIATION, OPINION AND EXPRESSION 27 B. FAIR TRIAL RIGHTS 29 C. ARBITRARY DETENTION 30 D. POLITICAL PERSECUTION AS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY 31 V. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 37 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY “An overdose of freedom is lethal to a state.” Vladislav Surkov, former adviser to President Putin and architect of Russia’s “managed democracy”.1 Russia is due to hold Parliamentary elections in September 2021. The ruling United Russia party is polling at 28% and is projected to lose its constitutional majority (the number of seats required to amend the Constitution).2 In a bid to silence its critics and retain control of the legislature, the Kremlin has unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on the pro-democracy movement, independent media, and anti-corruption activists. -

Post-Communist Mafia State

REVIEWS 275 tion’s wealth for themselves: rather, as is the Magyar, Bálint: case in Hungary, it could be a country whose corrupt, kleptocratic leaders also go out of POST-COMMUNIST MAFIA STATE. their way to actively control illicit societal THE CASE OF HUNGARY. activities and organized crime. These leaders do not simply steal from the state: they rot Budapest: Central European University it and create a society of thieves dependent Press. 2016. 311 pages. upon the elites who sanction their crimes (pp. 81–82). It is a vicious cycle that makes DOI: 10.5817/PC2018-3-275 everyone complicit in the state’s corruption. Magyar’s latest text successfully tests his An unequivocal condemnation of the Fi expanded theory of the mafia state, con deszcontrolled Hungary, Bálint Magyar’s cretizing it and demonstrating how Hun Post-Communist Mafia State: The Case of gary’s authoritarian government can mas Hungary could not be timelier. This book querade as a ‘good’ state whilst eroding civil explores the deceitful mechanisms by which society and democratic institutions – even the hybrid regime installed by Prime Min without exerting any physical mass violence ister Viktor Orbán and his fellow Fidesz of (see Levitsky, Lucan 2010). It argues that ficials has systematically stripped Hungari Hungary is a corrupt, parasitic state (p. 13). ans of civil liberties (p. 255) with impunity, The book begins with the premise that upon ironically owing to its control over the rule its accession to the European Union in 2004, of law. While this text specifically investi Hungary was the model of liberal democrat gates democratic backsliding in Hungary, its ic consolidation for other former Commu framework will surely prove crucial for un nist states. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Beyond Corporate Raiding: a Discussion of Advanced Fraud Schemes in the Russian Market

111th CONGRESS Printed for the use of the 2d Session Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe BEYOND CORPORATE RAIDING: A DISCUSSION OF ADVANCED FRAUD SCHEMES IN THE RUSSIAN MARKET NOVEMBER 9, 2010 Briefing of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe Washington: 2015 VerDate Sep 11 2014 04:03 Sep 01, 2015 Jkt 095243 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 3190 Sfmt 3190 E:\HR\OC\A243.XXX A243 smartinez on DSK4TPTVN1PROD with HEARINGS g:\graphics\CSCE.eps Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe 234 Ford House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 202–225–1901 [email protected] http://www.csce.gov Legislative Branch Commissioners SENATE HOUSE BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, MARYLAND, ALCEE L. HASTINGS, FLORIDA, Chairman Co-Chairman CHRISTOPHER DODD, CONNECTICUT EDWARD MARKEY, MASSACHUSETTS SAM BROWNBACK, KANSAS LOUISE MCINTOSH SLAUGHTER, SAXBY CHAMBLISS, GEORGIA NEW YORK RICHARD BURR, NORTH CAROLINA MIKE MCINTYRE, NORTH CAROLINA ROGER WICKER, MISSISSIPPI G.K. BUTTERFIELD, NORTH CAROLINA JEANNE SHAHEEN, NEW HAMPSHIRE JOSEPH PITTS, PENNSYLVANIA SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, RHODE ISLAND ROBERT ADERHOLT, ALABAMA TOM UDALL, NEW MEXICO DARRELL ISSA, CALIFORNIA EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS MICHAEL POSNER, Department of State ALEXANDER VERSHBOW, Department of Defense (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 04:03 Sep 01, 2015 Jkt 095243 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 3190 Sfmt 3190 E:\HR\OC\A243.XXX A243 smartinez on DSK4TPTVN1PROD with HEARINGS ABOUT THE ORGANIZATION FOR SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE The Helsinki process, formally titled the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, traces its origin to the signing of the Helsinki Final Act in Finland on August 1, 1975, by the leaders of 33 European countries, the United States and Canada. -

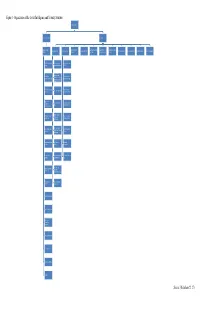

Organization of the Soviet Intelligence and Security Structure Source

Figure 1- Organization of the Soviet Intelligence and Security Structure General Chairman First Deputy Chairman Chief, GRU Deputy Chairman Space Intelligence Operational/ Technical Administrative/ Directorate for Foreign First Deputy Chief Chief of Information Personnel Directorate Political Department Financial Department Eighth Department Archives Department (KGB) Directorate Directorate Technical Directorate Relations First Chief Directorate First Directorate: Seventh Directorate: (Foreign) Europe and Morocco NATO Second Directorate: North and South Second Chief Eighth Directorate: America, Australia, Directorate (Internal) Individual Countries New Zealand, United Kingdom Fifth Chief Directorate Ninth Directorate: Third Directorate: Asia (Dissidents) Military Technology Eighth Chief Fourth Directorate: Tenth Directorate: Directorate Africa Military Economics (Communications) Fifth Directorate: Chief Border Troops Eleventh Directorate: Operational Directorates Doctrine, Weapons Intelligence Sixth Directorate: Third (Armed Forces) Twelfth Directorate: Radio, Radio-Technical Directorate Unknown Intelligence Seventh (Surveillance) First Direction: Institute of Directorate Moscow Information Ninth (Guards) Second Direction: East Information Command Directorate and West Berlin Post Third: National Technical Operations Liberation Directorate Movements, Terrorism Administration Fourth: Operations Directorate from Cuba Personnel Directorate Special Investigations Collation of Operational Experience State Communications Physical Security Registry and Archives Finance Source: (Richelson 22, 27) Figure 2- Organization of the United States Intelligence Community President National Security Advisor National Security DNI State DOD DOJ DHS DOE Treasury Commerce Council Nuclear CIO INR USDI FBI Intelligence Foreign $$ Flow Attachés Weapons Plans DIA NSA NGA NRO Military Services NSB Coast Guard Collection MSIC NGIC (Army) MRSIC (Air Analysis AFMic Force) NCTC J-2's ONI (Navy) CIA Main DIA INSCOM (Army) NCDC MIA (Marine) MIT Source: (Martin-McCormick) .