Driving, Dashboards and Dromology: Analysing 1980S Videogames Using Paul Virilio’S Theory of Speed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

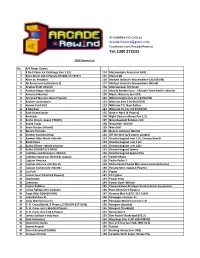

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

History of Technology in Games Themes the Early Days Hardware

Themes History of Technology in Games ! Technology’s impact on game design The Beginnings ! Hardware vs. Software (cyclic) CMPUT 250 ! Specialization vs. Generalization (cyclic) Fall 2007 ! State vs. Dynamics (cyclic) Tuesday, October 2 ! One Person vs. Teams (progression) CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 Lecture #8: History 1 The Early Days Hardware vs. Software ! The very earliest video games (pre-1975) ! Early switch to microprocessors were custom built machines ! General-purpose hardware that runs software ! Designed/built by engineers (like a TV) ! No need to engineer every game from scratch Tennis for Two (Brookhaven Labs,1958) Gunfight (Taito, 1975) CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 Lecture #8: History 1 Pong (Atari, 1972) Lecture #8: History 1 Software-Based Games Development of Early Games ! Once microprocessors were used for games, ! Programs written by one individual programmers took control ! Graphics, sound, controls, rules, AI… ! The advent of personal computers (~1976) …all by one person opened up the field to “amateurs” CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 Lecture #8: History 1 Lecture #8: History 1 Development of Early Games An Early Graphics Innovation ! Games were simple Breakout (Atari, 1976) ! The machines were simple ! Very limited storage and speed ! No “pictures” or recorded music ! Focus on moving small things around on the screen ! Only so much one could do ! More people would be a waste of effort Boot Hill (Midway, 1977) CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 CMPUT 250 - Fall 2007 Lecture #8: History 1 Lecture #8: History -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Finding Aid to the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records, 1969-2002

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records Finding Aid to the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records, 1969-2002 Summary Information Title: Atari Coin-Op Division corporate records Creator: Atari, Inc. coin-operated games division (primary) ID: 114.6238 Date: 1969-2002 (inclusive); 1974-1998 (bulk) Extent: 600 linear feet (physical); 18.8 GB (digital) Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English, although there a few instances of Japanese. Abstract: The Atari Coin-Op records comprise 600 linear feet of game design documents, memos, focus group reports, market research reports, marketing materials, arcade cabinet drawings, schematics, artwork, photographs, videos, and publication material. Much of the material is oversized. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) have not been transferred, The Strong has permission to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Conditions Governing Access: At this time, audiovisual and digital files in this collection are limited to on-site researchers only. It is possible that certain formats may be inaccessible or restricted. Custodial History: The Atari Coin-Op Division corporate records were acquired by The Strong in June 2014 from Scott Evans. The records were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 114.6238. -

Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow

San Francisco, California August 20-21, 2005 $5.00 Welcome to Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow .... eight years! It's truly amazing to think that we 've been doing this show, and trying to come up with a fresh introduction for this program, for eight years now. Many things have changed over the years - not the least of which has been ourselves. Eight years ago John was a cable splicer for the New York phone company, which was then called NYNEX, and was happily and peacefully married to his wife Beverly who had no idea what she was in for over the next eight years. Today, John's still married to Beverly though not quite as peacefully with the addition of two sons to his family. He's also in a supervisory position with Verizon - the new New York phone company. At the time of our first show, Sean was seven years into a thirteen-year stint with a convenience store he owned in Chicago. He was married to Melissa and they had two daughters. Eight years later, Sean has sold the convenience store and opened a videogame store - something of a life-long dream (or was that a nightmare?) Sean 's family has doubled in size and now consists of fou r daughters. Joe and Liz have probably had the fewest changes in their lives over the years but that's about to change . Joe has been working for a firm that manages and maintains database software for pharmaceutical companies for the past twenty-some years. While there haven 't been any additions to their family, Joe is about to leave his job and pursue his dream of owning his own business - and what would be more appropriate than a videogame store for someone who's life has been devoted to collecting both the games themselves and information about them for at least as many years? Despite these changes in our lives we once again find ourselves gathering to pay tribute to an industry for which our admiration will never change . -

United States Bankruptcy Court SUMMARY of SCHEDULES

13-10176-jmp Doc 119 Filed 03/06/13 Entered 03/06/13 20:14:12 Main Document Pg 1 of 110 B6 Summary (Official Form 6 - Summary) (12/07) }bk1{Form 6.Suayfchedls United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of New York In re Atari Interactive, Inc. Case No. 13-10177 , Debtor Chapter 11 SUMMARY OF SCHEDULES Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor’s assets. Add the amounts of all claims from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor’s liabilities. Individual debtors must also complete the "Statistical Summary of Certain Liabilities and Related Data" if they file a case under chapter 7, 11, or 13. NAME OF SCHEDULEATTACHED NO. OF ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER (YES/NO) SHEETS A - Real Property Yes 10.00 B - Personal Property Yes 4 21,238,150.00 C - Property Claimed as Exempt No 0 D - Creditors Holding Secured Claims Yes 1 0.00 E - Creditors Holding Unsecured Yes 1 0.00 Priority Claims (Total of Claims on Schedule E) F - Creditors Holding Unsecured Yes 1 266,183,594.00 Nonpriority Claims G - Executory Contracts and Yes 1 Unexpired Leases H - Codebtors Yes 1 I - Current Income of Individual No 0 N/A Debtor(s) J - Current Expenditures of Individual No 0 N/A Debtor(s) Total Number of Sheets of ALL Schedules 10 Total Assets 21,238,150.00 Total Liabilities 266,183,594.00 Software Copyright (c) 1996-2013 - CCH INCORPORATED - www.bestcase.com Best Case Bankruptcy 13-10176-jmp Doc 119 Filed 03/06/13 Entered 03/06/13 20:14:12 Main Document Pg 2 of 110 B6A (Official Form 6A) (12/07) }bk1{Schedul A-RaPropty In re Atari Interactive, Inc. -

3500-Arcadegamelist.Pdf

No. GameName PlayersGroup 1 10 Yard Fight <Japan> Sport 2 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) Driving 3 18 Challenge Pro Golf (DECO,Japan) Sport 4 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) Sport 5 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) Shoot 6 1942 (Revision B) Shoot 7 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) Shoot 8 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) Shoot 9 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) Shoot 10 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) Shoot 11 19XX:The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Shoot 12 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 3/4P Sport 13 2020 Super Baseball <set 1> Sport 14 3 Count Bout/Fire Suplex Fighter 15 3D_Aqua Rush (JP) Ver. A Maze 16 3D_Battle Arena Toshinden 2 Fighter 17 3D_Beastorizer (US) Fighter 18 3D_Beastorizer <US *bootleg*> Fighter 19 3D_Bloody Roar 2 <Japan> Fighter 20 3D_Brave Blade <Japan> Fighter 21 3D_Cool Boarders Arcade Jam (US) Sport 22 3D_Dancing Eyes <Japan ver.A> Adult 23 3D_Dead or Alive++ Fighter 24 3D_Ehrgeiz (US) Ver. A Fighter 25 3D_Fighters Impact A (JP 2.00J) Fighter 26 3D_Fighting Layer (JP) Ver.B Fighter 27 3D_Gallop Racer 3 (JP) Sport 28 3D_G-Darius (JP 2.01J) Sport 29 3D_G-Darius Ver.2 (JP 2.03J) Sport 30 3D_Heaven's Gate Fighter 31 3D_Justice Gakuen (JP 991117) Fighter 32 3D_Kikaioh (JP 980914) Fighter 33 3D_Kosodate Quiz My Angel 3 (JP) Ver.A Maze 34 3D_Magical Date EX (JP 2.01J) Maze 35 3D_Monster Farm Jump (JP) Maze 36 3D_Mr Driller (JP) Ver.A Maze 37 3D_Paca Paca Passion (JP) Ver.A Maze 38 3D_Plasma Sword (US 980316) Fighter 39 3D_Prime Goal EX (JP) Sport 40 3D_Psychic Force (JP 2.4J) Fighter 41 3D_Psychic Force (World 2.4O) Fighter 42 3D_Psychic Force EX (JP 2.0J) Fighter 43 3D_Raystorm (JP 2.05J) Shoot 44 3D_Raystorm (US 2.06A) Shoot 45 3D_Rival Schools (ASIA 971117) Fighter 46 3D_Rival Schools <US 971117> Fighter 47 3D_Shanghai Matekibuyuu (JP) Maze 48 3D_Sonic Wings Limited <Japan> Shoot 49 3D_Soul Edge (JP) SO3 Ver. -

4539-Arcadegamelist.Pdf

1 005 80 3D_Tekken (WORLD) Ver. B 157 Alien Storm (Japan, 2 Players) 2 1 on 1 Government (Japan) 81 3D_Tekken <World ver.c> 158 Alien Storm (US,3 Players) 3 10 Yard Fight <Japan> 82 3D_Tekken 2 (JP) Ver. B 159 Alien Storm (World, 2 Players) 4 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 83 3D_Tekken 2 (World) Ver. A 160 Alien Syndrome 5 10-Yard Fight ‘85 (US, Taito license) 84 3D_Tekken 2 <World ver.b> 161 Alien Syndrome (set 6, Japan, new) 6 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 85 3D_Tekken 3 (JP) Ver. A 162 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520 Phoenix Edition) 7 1941: Counter Attack (USA 900227) 86 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 163 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520) 8 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) 87 3D_Tondemo Crisis 164 Alien vs. Predator (Hispanic 940520) 9 1942 (Revision B) 88 3D_Toshinden 2 165 Alien vs. Predator (Japan 940520) 10 1942 (Tecfri PCB, bootleg?) 89 3D_Xevious 3D/G (JP) Ver. A 166 Alien vs. Predator (USA 940520) 11 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) 90 3X3 Maze (Enterprise) 167 Alien3: The Gun (World) 12 1943: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 91 3X3 Maze (Normal) 168 Aliens <Japan> 13 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) 92 4 En Raya 169 Aliens <US> 14 1944: The Loop Master (USA Phoenix Edition) 93 4 Fun in 1 170 Aliens <World set 1> 15 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) 94 4-D Warriors 171 Aliens <World set 2> 16 1945 Part-2 (Chinese hack of Battle Garegga) 95 600 172 All American Football (rev D, 2 Players) 17 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) 96 64th. -

2600 in 1 Game List

2600 in 1 Game List www.myarcade.com.au # Name 50 Agu's Adventure 1 005 51 Air Attack (set 1) 2 10-Yard Fight 52 Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit (World) 3 12Yards 53 Air Combat 4 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 54 Air Command 5 1942 (Revision A) 55 Air Duel (Japan) 6 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 56 Air Gallet (Europe) 7 1943: The Battle of Midway (US, Rev C) 57 Air Strike 8 1943:The Battle of Midway 58 Airwolf 9 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 59 Ajax 10 1945k III 60 Akkanbeder 11 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 61 Aladdin Fairy Tale 12 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 62 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 13 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043) 63 Alibaba and 40 Thieves (NGH043) 64 Alien Arena 14 4 En Raya (set 1) 65 Alien Challenge (World) 15 4 Fun in 1 66 Alien Sector 16 4-D Warriors (315-5162) 67 Alien Storm (World, 2 Players, FD1094 317- 17 5-Person Volleyball 0154) 18 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 68 Alien Syndrome (set 4, System 16B, 19 8 Billiards unprotected) 20 800 Fathoms 69 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520) 21 '88 Games 70 Aliens (World set 1) 22 8Th Heat Output 71 All American Football 23 9 Ball Shootout 72 Alligator Hunt 24 99:The Last War 73 Alpha Mission 25 9Th Forward 2 74 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian (NGM- 26 A Beautiful New World 007)(NGH-007) 27 A Drop Of Dawn Water 75 Alpha One 28 A Drop Of Dawn Water 2 76 Alpine Ski (set 1) 29 A Hero Like Me 77 Alsen 30 A Sword 78 Altered Beast (set 8, 8751 317-0078) 31 A.D.2083 79 Amazing World 32 Abscam 80 American Speedway -

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. Game Name Players No. Game Name Players 1 10 Yard Fight <Japan> 1751 Meikyu Jima <Japan> 2 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 1752 Mello Yello Q*bert 3 18 Challenge Pro Golf (DECO,Japan) 1753 Mercs <US> 3/4P 4 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 1754Mercs <World> 3/4P 5 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) 1755 Merlins Money Maze 6 1942 (Revision B) 1756Mermaid 7 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) 1757 Meta Fox 8 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) 1758 Metal Black <World> 9 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) 1759 Metal Clash <Japan> 10 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) 1760 Metal Hawk (Rev C) 11 19XX:The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 1761 Metal Saver 12 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 3/4P 1762 Metal Slug 2-Super Vehicle-001/II 13 2020 Super Baseball <set 1> 1763 Metal Slug 3 14 3 Count Bout/Fire Suplex 1764 Metal Slug 4 15 3D_Aqua Rush (JP) Ver. A 1765 Metal Slug 4 (NGM-2630) 16 3D_Battle Arena Toshinden 2 1766 Metal Slug 4 Plus 17 3D_Beastorizer (US) 1767 Metal Slug 4 Plus (Alternate) 18 3D_Beastorizer 1768Metal Slug 5 19 3D_Bloody Roar 2 <Japan> 1769 Metal Slug 5 (NGM-2680) 20 3D_Brave Blade <Japan> 1770 Metal Slug 6 21 3D_Cool Boarders Arcade Jam (US) 1771 Metal Slug X-Super Vehicle-001 22 3D_Dancing Eyes <Japan ver.A> 1772 Metal Slug-Super Vehicle-001 23 3D_Dead or Alive++ 1773 Metamoqester 24 3D_Ehrgeiz (US) Ver. -

Atari IP Catalog 2016 IP List (Highlighted Links Are Included in Deck)

Atari IP Catalog 2016 IP List (Highlighted Links are Included in Deck) 3D Asteroids Atari Video Cube Dodge ’Em Meebzork Realsports Soccer Stock Car * 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Avalanche * Dominos * Meltdown Realsports Tennis Street Racer A Game of Concentration Backgammon Double Dunk Micro-gammon Realsports Volleyball Stunt Cycle * Act of War: Direct Action Barroom Baseball Drag Race * Millipede Rebound * Submarine Commander Act of War: High Treason Basic Programming Fast Freddie * Mind Maze Red Baron * Subs * Adventure Basketball Fatal Run Miniature Golf Retro Atari Classics Super Asteroids & Missile Adventure II Basketbrawl Final Legacy Minimum Return to Haunted House Command Agent X * Bionic Breakthrough Fire Truck * Missile Command Roadrunner Super Baseball Airborne Ranger Black Belt Firefox * Missile Command 2 * RollerCoaster Tycoon Super Breakout Air-Sea Battle Black Jack Flag Capture Missile Command 3D Runaway * Super Bunny Breakout Akka Arrh * Black Widow * Flyball * Monstercise Saboteur Super Football Alien Brigade Boogie Demo Food Fight (Charley Chuck's) Monte Carlo * Save Mary Superbug * Alone In the Dark Booty Football Motor Psycho Scrapyard Dog Surround Alone in the Dark: Illumination Bowling Frisky Tom MotoRodeo Secret Quest Swordquest: Earthworld Alpha 1 * Boxing * Frog Pond Night Driver Sentinel Swordquest: Fireworld Anti-Aircraft * Brain Games Fun With Numbers Ninja Golf Shark Jaws * Swordquest: Waterworld Aquaventure Breakout Gerry the Germ Goes Body Off the Wall Shooting Arcade Tank * Asteroids Breakout * Poppin Orbit * Sky Diver