Between Ceasefires and Federalism: Exploring Interim Arrangements in the Myanmar Peace Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TANINTHARYI REGION, MYEIK DISTRICT Palaw Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census TANINTHARYI REGION, MYEIK DISTRICT Palaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Tanintharyi Region, Myeik District Palaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Tanintharyi Region, showing the townships Palaw Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 93,438 2 Population males 45,366 (48.6%) Population females 48,072 (51.4%) Percentage of urban population 20.3% Area (Km2) 1,652.3 3 Population density (per Km2) 56.6 persons Median age 22.9 years Number of wards 5 Number of village tracts 20 Number of private households 18,525 Percentage of female headed households 24.2 % Mean household size 5.0 persons4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 35.7% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 58.8% Elderly population (65+ years) 5.5% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 70.1 Child dependency ratio 60.7 Old dependency ratio 9.4 Ageing index 15.5 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 94 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 94.4% Male 94.9% Female 94.0% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 9,018 9.7 Walking 3,137 3.4 Seeing 5,655 6.1 Hearing 2,464 2.6 Remembering 2,924 3.1 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 51,835 -

Out of the Ord Ary Tours for Everyone

Explore Asia 2016 - 2017 Out of the ordary Tours for everyone Great Outdoors · Local Customs · Charming Hospitality · Traditional Cooking · Stimulating Art · Intriguing Architecture 2 map asia & content introduction 3 1 Discover the home of the Padaung >> pages 4–5 CHINA Shanghai 2 West Sumatra – The Highlands and Mekong (Lancang) River the Sea 8 Chengdu >> pages 6–7 Xiamen 3 Local Immersions in Lak >> pages 8–9 MYANMAR Mandalay OUT OF THE OR DINA RY LAOS philippine sea 4 Rural Glamping by Jeep to Banteay Luang Prabang TOURS FOR EV ERYONE Hanoi Ampil 1 5 >> pages 10–11 Padaung Yangon Our programmes take individuals 5 A culinary journey through Laos and small groups in an exciting new THAILAND vietnam >> pages 12–13 4 travel direction and provide unique, Banteay Ampil Bangkok south out of the ordinary experiences. 3 Lak 6 The Hidden Trails of Phuket china CAMBODIA sea >> pages 14–15 Ho Chi Our guests can achieve a truly Minh City authentic and sustainable travel 7 Authentic Sarawak 6 experience in the great, wide Phuket >> pages 16–17 outdoors. We cater for those with a passion for indigenous customs 8 Sichuan Exploration MALAYSIA and culture; charming hospitality; Kuala Lumpur MALAYSIA >> page 18–19 Sarawak 7 flavoursome and traditional 2 cooking; stimulating ethnic art; and indian ocean Padang intriguing architecture. INDONESIA INDONESIA come explore with us. Jakarta 8 Bali Lombok 4 myanmar • 2016 - 2017 myanmar • 2016 - 2017 5 1 · Inle Sagar Pagodas 2 · Village in mountain landscape 3 · Kalaw Market Discover the home of the Padaung 4 · Taung Kwe Zedi 5 · Long Neck Padaung Highlights › Visit Loikaw, the capital of Kayah State, and experience a wealth of fascinating cultural sites › Learn more about the unique “long neck” Padaung women › Explore untouched country side and interact with Kayan tribespeople in a verdant tropical landscape Loikaw, the capital of Kayah State, day 1, Inle Lake – Loikaw local life and customs is to visit a Myanmar’s most famous hill stations. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Literature for the SECU Desk Review Dear Paul, Anne and the SECU

Literature for the SECU Desk Review Dear Paul, Anne and the SECU team, We are writing to you to provide you with what we consider to be important documents in your investigation into community complaints of the Ridge to Reef Project. The following documents provide background to the affected community and the political situation in Tanintharyi Region, on the history and design of the project, on the grievances and concerns of the local community with respect to the project, and aspirations and efforts of indigenous communities who are working towards an alternative vision of conservation in Tanintharyi Region. The documents mentioned in this letter are enclosed in this email. All documents will be made public. Background to the affected community Tanintharyi Region is home to one of the widest expanses of contiguous low to mid elevation evergreen forest in South East Asia, home to a vast variety of vulnerable and endangered flora and fauna species. Indigenous Karen communities have lived within this landscape for generations, managing land and forests under customary tenure systems that have ensured the sustainable use of resources and the protection of key biodiversity, alongside forest based livelihoods. The region has a long history of armed conflict. The area initially became engulfed in armed conflict in December 1948 when Burmese military forces attacked Karen Defence Organization outposts and set fire to several villages in Palaw Township. Conflict became particularly bad in 1991 and 1997, when heavy attacks were launched by the Burmese military against KNU outposts, displacing around 80,000 people.1 Throughout the conflict communities experienced many serious human rights abuses, many villages were burnt down, and tens of thousands of people were forced to flee to the Thai border, the forest or to government controlled zones.2 Armed conflict came to a halt in 2012 following a bi-lateral ceasefire agreement between the KNU and the Myanmar government, which was subsequently followed by KNU signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement in 2015. -

PA) PROFILES LENYA LANDSCAPE (“R2R Lenya”, Aka Lenya Proposed Protected Area, Which Is Currently Lenya Reserved Forest

ANNEX 11: Lenya Profile LANDSCAPE / SEASCAPE AND PROTECTED AREA (PA) PROFILES LENYA LANDSCAPE (“R2R Lenya”, aka Lenya Proposed Protected Area, which is currently Lenya Reserved Forest) Legend for this map of Lenya Landscape is provided at the end of this annex. I. Baseline landscape context 1. 1 Defining the landscape: Lenya Landscape occupies the upper Lenya River Basin in Kawthaung District, and comprises the Lenya Proposed National Park (LPNP), which was announced in 2002 for the protection of Gurney’s pitta and other globally and nationally important species, all of which still remain (see below). The LPNP borders align with those of the Lenya Reserve Forest (RF) under which the land is currently classified, however its status as an RF has to date not afforded it the protection from encroachment and other destructive activities to protect the HCVs it includes. The Lenya Proposed National Park encompasses an area of 183,279ha directly south of the Myeik-Kawthaung district border, with the Lenya Proposed National Park Extension boundary to the north, the Parchan Reserve Forest to the south and the Thai border to the east. The site is located approximately 260km south of the regional capital of Dawei and between 20-30km east of the nearest administrative town of Bokpyin. Communities are known to reside within the LPNP area as well as on its immediate boundaries across the LPNP. Some small settled areas can be found in the far south-east, along the Thai border, where heavy encroachment by smallholder agriculture can also be found and where returning Myanmar migrants to Thailand may soon settle; Karen villages which have resettled (following the signing of a peace treaty between the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Myanmar government) on land along the Lenya River extending into the west of LPNP; and in the far north where a significant number of hamlets (in addition to the Yadanapon village) have developed in recent years along the the Yadanapon road from Lenya village to Thailand. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Annex 8 Myanmar

Sustainable Management of Peatland Forests in Southeast Asia SEApeat Project - Myanmar Component Progressive Report for First Quarter 2014 Description of Project in brief Component/Country : The Republic of Union of Myanmar Project Period : One years (2014) Project Budget : USD 49,000 Funding Agency : European Union (EU) through Global Environment Centre (GEC ) Regional Implementing : Global Environmental Centre Agency (GEC) Focal Point : Environmental Conservation Department (ECD) Implementing Partner : FREDA in cooperation with ECD and FD (MOECAF), AD and SLRD (MAI) Activities to be implemented in 2014 1. Technical Workshop on Sustainable Peatland Management 2. Replicated trainings and Peat Assessment 3. Pilot-testing – for best management practices of peatland 4. Awareness and Education Campaign Achievement so far: (1) Technical Workshop on Sustainable Peatland Management (2) Coordination meetings (3) Trainings and awareness campaign (4) Peat Assessment (i) Ayeyarwady Region (ii) Shan State (iii) Thanintharyi Region Technical Workshop on Sustainable Peatland Management Venue : Tungapuri Hotel, Yarza Thingaha Rd, Nay Pyi Taw Date : 30th January, 2014 Attendees : (61) persons who are the most responsible and interested staff of Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, University of Agriculture, University of Forestry, NGOs, Global Environmental Centre (GEC) and FREDA Deputy Ministers, Dr. Daw Thet Thet Zin and U Aye Myint Maung attended the Workshop and Dr. Daw Thet Thet Zin delivered the opening speech. Deputy Ministers of MOECAF viewing the display at Technical Workshop Technical Workshop being in session Workshop Presentations 1. Sustainable Peatland Management in South East Asia by GEC 2. SEApeat Project (Myanmar Component) by ECD (MOECAF) 3. Some facts about Peat Soil and Peatland by FREDA 4. -

Yangon University of Economics Department of Economics Master of Development Studies Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME A STUDY ON WOMEN PARTICIPATION IN THE KACHIN LITERATURE AND CULTURE ASSOCIATION, LASHIO, NORTHERN SHAN STATE L JI MAI EMDEVS -16 (15TH BATCH) NOVEMBER, 2019 i YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME This is to certify that thesis entitled “A Study on Women Participation in the Kachin Literature and Culture Association, Lashio” submitted as a partial fulfillment toward the requirements for the degree of Master of Development Studies, has been accepted by the Board of Examiners. BOARD OF EXAMINERS 1. Dr. Tin Win Rector Yangon University of Economics (Chief Examiner) 2. Dr. Ni Lar Myint Htoo Pro-Rector Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 3. Dr. Kyaw Min Tun Pro- Rector (Retired) Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 4. Dr. Cho Cho Thein Professor and Head Department of Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 5. Daw Yin Myo Oo Associate Professor Department of Econimics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) November, 2019 ii YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME A STUDY ON WOMEN PARTICIPATION IN THE KACHIN LITERATURE AND CULTURE ASSOCIATION, LASHIO A thesis submitted as a partial fulfilment towards the requirement of the Degree of Master of Development Studies (EMDevS) Supervised by: Submitted by: Daw Than Win Htay L Ji Mai Lecturer Roll No.16 Department of Economics EMDevs -15th batch Yangon University of Economics (2017-2019) November, 2019 iii ABSTRACT In Myanmar, women are still mostly excluded from full and equal participation in decision-making and leadership at all levels of society due to the traditional culture, norms, and stereotypes which favour and prefer men to take up leadership opportunities. -

The Burma Army's Offensive Against the Shan State Army

EBO The Burma Army’s Offensive Against the Shan State Army - North ANALYSIS PAPER No. 3 2011 THE BURMA ARMY’S OFFENSIVE AGAINST THE SHAN STATE ARMY - NORTH EBO Analysis Paper No. 3/2011 On 11 November 2010, a fire fight between troops of Burma Army Light Infantry Division (LID) 33 and Battalion 24 of the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N) 1st Brigade at Kunkieng-Wanlwe near the 1st Brigade’s main base, marked the beginning of the new military offensive against the ethnic armed groups in Shan and Kachin States. Tensions between the Burma Army and the ethnic groups, which had ceasefire agreements, started to mount after the Burma Army delivered an ultimatum in April 2009 for the groups to become Border Guard Forces. Prior to this, the Burma Army had always maintained that it did not have jurisdiction over political issues and that the groups could maintain their arms and negotiate with the new elected government for a political solution. Most of the larger ethnic groups refused to become BGFs, and in August 2009 the Burma Army attacked and seized control of Kokang (MNDAA), sending shock waves through the ethnic communities and the international community. Following the outcry, the Burma Army backed down and seemed content to let matters die down as it concentrated on holding the much publicized general elections on 7 November 2010. The attack against the SSA-N is seen was the first in a series of military offensives designed to fracture and ultimately destroy all armed ethnic opposition in the country’s ethnic borderlands.1 While the SSA-N lost its bases, this is unlikely to reduce its ability to conduct guerrilla operation against the Burma Army. -

Contributions to the Flora of Myanmar Ii: New Records of Eight Woody Species from Tanintharyi Region, Southern Myanmar

NAT. HIST. BULL. SIAM SOC. 63(1): 47–56, 2018 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE FLORA OF MYANMAR II: NEW RECORDS OF EIGHT WOODY SPECIES FROM TANINTHARYI REGION, SOUTHERN MYANMAR Shuichiro Tagane1,2*, Nobuyuki Tanaka3, Mu Mu Aung4, Akiyo Naiki5 and Tetsukazu Yahara1 ABSTRACT The fieldwork carried out in Tanintharyi Region in 2016 resulted in the discovery of eight unrecorded angiosperms among the flora of Myanmar. They are Mitrephora winitii Craib (Annonaceae), Argyreia roseopurpurea (Kerr) Ooststr. (Convolvulaceae), Diospyros bejaudii Lecomte (Ebenaeae), Cladogynos orientalis Zipp. ex Span. (Euphorbiaceae), Callicarpa furfuracea Ridl. (Lamiaceae), Memecylon paniculatum Jack (Melastomataceae), Ardisia congesta Ridl. (Primulaceae) and Coelospermum truncatum (Wall.) Baill. ex K. Schum. (Rubiaceae). In each of the species, voucher specimens, the general distribution and photographs are presented. Keywords: angiosperm, flora, Myanmar, new record, Tanintharyi, woody plant INTRODUCTION The Tanintharyi Region (formerly Tenasserim), located at the northwestern part of the Thai–Malay Peninsula, is a part of the Indo–Burma biodiversity hotspot, with the Indochinese– Sundaic flora and fauna transition (MYERS ET AL., 2000; TORDOFF ET AL., 2012). The area is still predominantly forested, ca. 80% of a total land area of 43,000 km2, but recently large areas have been selectively logged and converted to agricultural land (CONNETTE ET AL., 2016). The vegetation is diverse along with elevational gradients, heterogeneous landscapes and geologi- cal conditions including granite, sandstone, shale and spectacular karst limestone (DE TERRA, 1944; BENDER, 1983), which drove the diversification of plants to high endemism. In spite of the high value of biodiversity of the area, the area is poorly known botani- cally. It had not been surveyed for over 40 years until 1996, mainly because of the tumultuous history of the civil war and conflict at the end of World War II. -

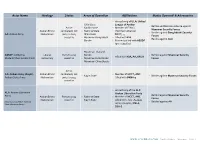

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security