Colonial Urbanization: Nanyuki Town, Kenya, 1921

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE PROF. FUCHAKA WASWA [(BSc. Agric (Nairobi), MSc. Land & Water Management (Nairobi), PhD (Bonn)] Associate Professor of Environmental Agriculture (Area of specialization: Agricultural Land & Water Management) 1. PERSONAL PROFILE Personal Details Name: Fuchaka Waswa PF No.: 6243 School: Agriculture & Enterprise Development Department: Agricultural Science and Technology Designation: Associate Professor Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Cell phone: + 254-723-580126 Research Interests 1. Agricultural Land Management and Policy 2. Food Security Planning and Policy 3. Corporate and Intellectual Social Responsibility 4. Industrial Ecology and Sustainable Life Styles Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID): https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0675-1441 2. ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Academic Certificate Institution Specialisation Awarded PhD University of Bonn Agricultural Land Management 2000 MSc University of Nairobi Land and Water Management 1994 BSc University of Nairobi General Agriculture 1992 KACE Kericho High School 3 Principals & 2 Subsidiaries 1987 KCE Chebuyusi Sec. School. Division 1, 13 Points 1985 Professional Qualifications 1. Environmental Impact Assessment & Auditing (Registered Lead Expert No. 0643) 2. Conducting and Using the Millennium Ecosystem Assessments Framework 3. Quality Assurance in Higher Education with focus on: Auditing and Rationalisation of University Academic Programmes and Units Competence-based Learning Organisational Development and Change Management Research Excellence and Knowledge Management Teamwork and Team Dynamics Training in Transformative Leadership in Higher Education 1 CV-Fuchaka Short Courses and Trainings in Higher Education 1. 24th – 27th April 2019: As a team member in module development and member of KDSA, I participated in the first pilot workshop on the training of university leaders Courtesy DAAD and the Commission for University Education, held at lake Naivasha Simba Lodge, Kenya. -

Driving Directions

Routes from Nairobi to Rhino River Camp (by road). (Consider a six hours drive). From central Nairobi (via Museum Hill) take Thika road. Past Thika and before Sagana there is a junction: to the left the road goes towards Nyeri and Nanyuki, to the right it goes to Embu. First option: going left toward Nyeri-Nanyuki. Drive through Sagana, then Karitina. After 13 kms, there is a junction where you should turn right. At junction, instead of going straight to the road bound to Nyeri, take the road towards Naro Moru and Mt. Kenya. After Nanyuki proceed straight to Meru. The only major junction in the road Nanyuki-Meru is the one going to Isiolo which you disregard and proceed straight to Meru Town. At Meru Town, at the first major junction (see Shell station on your left), turn left toward Maua. After driving about 45 kms over the Nyambeni hills on this road find the junction at 2 km before Maua. This junction is plenty of signposts one of which is a KWS sign with Meru National Park. Turn left and start descending towards Meru National Park; proceed for 25 km until Murera Gate (main gate) of the Park. In the Park: Enter the Park and go for about 1.5 km till you reach the old gate. Do a sharp right turn immediately after the old gate (in fact is more of a U turn) and enter the Rhino Sanctuary passing under an elephant wired fence. Follow the Park fence going South. The fence is on your right and there are a few deviation but you have to always go back to the fence. -

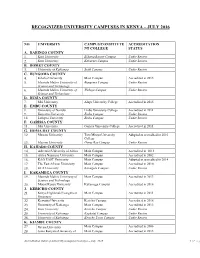

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Kenya, Groundwater Governance Case Study

WaterWater Papers Papers Public Disclosure Authorized June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA GROUNDWATER GOVERNANCE CASE STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Albert Mumma, Michael Lane, Edward Kairu, Albert Tuinhof, and Rafik Hirji Public Disclosure Authorized Water Papers are published by the Water Unit, Transport, Water and ICT Department, Sustainable Development Vice Presidency. Water Papers are available on-line at www.worldbank.org/water. Comments should be e-mailed to the authors. Kenya, Groundwater Governance case study TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................................. vi ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................ viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................ xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... xiv 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. GROUNDWATER: A COMMON RESOURCE POOL ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2. CASE STUDY BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. -

Dr. Stanley Wambugu Kahuthu

Dr. Stanley Wambugu Kahuthu PF No. 7801 9th;April;2021 1 PERSONAL DETAILS Cell Phone Number Phone: +254 721 273 909 or +254 739 049 099 E-mail Address [email protected] Nationality Kenyan County Nyeri Working Station Kenyatta University Institution Contact Address P.O. Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, KENYA My Corporate E-mail [email protected] 2 Interest • Reading scientific journal • Teaching/Lecturing • Reading the bible and Preaching • Doing Physical Exercises 3 Education Kenyatta University, Nairobi, KENYA August 2011 –18thDecember;2020 Task Doctoro f Philosophy UniversityofNairobi;Nairobi;KENYASeptember;2006 − −November;2008 1 Task Mastero f ScienceinSolidStatePhysics(Theoretical) Egerton University, Njoro, KENYA March, 1992–September, 2006 Task Bachelor of Education (Maths and Physics) Kenyatta High School-Mahiga, Nyeri, KENYA January, 1986–December, 1996 Task Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education 4 PERSONAL ACHIEVEMENTS In year 2000, I was awarded as the best Physics teacher in Nyeri county. 5 TECHNICAL SKILLS Programming and Scripting Language: C, C++, Scripting, MATLAB, Mathematica Operating Systems: Windows, Linux, Mac OSX Tools: Latex, MS-Access 6 COMPUTATIONAL SKILLS Quantum ESPRESSO: Ground properties of materials Yambo: Excited and opto-electronic properties of materials from semi-empirical method BerkeleyGW: Excited and opto-electronic properties of materials from the first principle 7 RESPONSIBILITIES • Departmental resentative of Community Out-reach on Environmental Policy. • From 2009 to 2011, I was class advisor of Physics students in Kagumo Teachers’ Training College as well as the treasurer of academic staff welfare. • In January, 2010, I was appointed to be an assistant Teaching Practice Zonal Coordinator of Muranga County; the position that I held till I left Kagumo Teachers’ Training College on 18th August, 2011. -

Pachyderm 44.Indd

Probable extinction of the western black rhino MANAGEMENT Biological management of the high density black rhino population in Solio Game Reserve, central Kenya Felix Patton, Petra Campbell, Edward Parfet c/o Solio Ranch, PO Box 2, Naro Moru, Kenya; email: [email protected] Abstract Optimising breeding performance in a seriously endangered species such as the black rhinoceros (Diceros bi- cornis) is essential. Following an estimation of the population demography of the black rhinos in Solio Game Reserve, Kenya and a habitat evaluation, a model of the Ecological Carrying Capacity showed there was a seri- ous overstocking. Data analysis of the first year of rhino monitoring indicated a poor breeding performance of 3.8% and a poor inter-calving interval in excess of 36 months. Biological management was required to improve the performance of the population by the removal of a significant number of individuals – 30 out of the 87. The criteria for selection were: to take no young animals i.e. around 3.5 years of age, to take no breeding females i.e. those with calves, to take care to maintain some breeding males in Solio, to attempt to ensure some breed- ing males are part of the ‘new’ population, to take care to leave a balanced population, to take care to create a balanced population in the ‘new’ population, to move those individuals that were hard to identify and to keep individuals which were easy for visitors to see. The need for careful candidate selection, the comparison of the population demography pre- and post-translocation, and the effect of the translocation activity on the remaining Solio population are discussed. -

African Studies Collection 63 an Ethnography of the World of Thean Ethnography World

Marlous van den Akker African Studies Collection 63 Monument of Monument of nature? Monument of nature? nature? Monument of nature? an ethnography of the World Heritage of Mt. Kenya an ethnography of the World an ethnography of the World examines the World Heritage status of Mt. Kenya, an alpine area located in Central Kenya. In 1997 Mt. Kenya joined the World Heritage List due to Heritage of Mt. Kenya its extraordinary ecological and geological features. Nearly fifteen years later, Mt. Kenya World Heritage Site expanded to incorporate a wildlife conservancy bordering the mountain in the north. Heritage of Mt. Kenya Both Mt. Kenya’s original World Heritage designation and later adjustments were founded on, and exclusively formulated in, natural scientific language. This volume argues that this was an effect not only of the innate qualities of Mt. Kenya’s landscape, but also of a range of conditions that shaped the World Heritage nomination and modification processes. These include the World Heritage Convention’s rigid separation of natural and cultural heritages that reverberates in World Heritage’s bureaucratic apparatus; the ongoing competition between two government institutes over the management of Mt. Kenya that finds its origins in colonial forest and game laws; the particular composition of Kenya’s political arena in respectively the late 1990s and the early 2010s; and the precarious position of white inhabitants in post-colonial Kenya that translates into permanent fears for losing Marlous van den Akker property rights. Marlous van den Akker (1983) obtained a Master’s degree in cultural anthropology from the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology at Leiden University in 2009. -

N O Institution's Name Public University 1 Chuka University 2 Dedan Kimathi University of Technology 3 Egerton University 4 Ja

N Institution’s Name o Public University 1 Chuka University 2 Dedan Kimathi University of Technology 3 Egerton University 4 Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology 5 Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture & Technology (JKUAT) 6 Karatina University 7 Kenyatta University 8 Kisii University 9 Laikipia University 10 Masai Mara University 11 Maseno University 12 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology 13 Meru University of Science and Technology 14 Moi University 15 Multi Media University 16 Pwani University 17 South Eastern Kenya University 18 Technical Univeristy of Mombasa 19 Technical University of Kenya 20 University of Eldoret 21 University of Kabianga 22 University of Nairobi Private University 23 Adventist University of Africa 24 Africa International University 25 Africa Nazarene University 26 Aga Khan University 27 Catholic University Of Eastern Africa 28 Daystar University 29 East African University 30 Great Lakes University 31 International University of Professional Studies 32 International Leadership University 33 Kabarak University 34 KCA University 35 Kenya Methodist University 36 Mount Kenya University 37 Pan Africa Christian University 38 Pioneer International University 39 Scott Christian University 40 St Paul's University 41 Strathmore University 42 The Management University of Africa 43 The Presbyterian University of East Africa 44 Umma University 45 United States International University 46 University of Eastern Africa, Baraton University College 47 Co-operative University College 48 Embu -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

KENYA - ROAD CONDITIONS UPDATE - 15Th Nov'06

KENYA - ROAD CONDITIONS UPDATE - 15th Nov'06 S U D A N Oromiya SNNP E T H I O P I A Somali Lokichoggio Lokitaung Lokichoggio & a n Mandera a (! Kakuma k r $+ Kakuma u T . & SolT olo MANDERA L Moyale T (! TURKANA North Horr Lodwar MOYALE T $+(! MARSABIT Gedo Karamoyo T Marsabit (! L. Logipi $+ T Lokori Baragoi Wajir U G A N D A (! WEST POKTOT Laisamis $+ Kacheliba Sigor Middle Juba SAMBURU WAJIR Kapenguria (! T TRANS NZOIA Maralal MARAKWET Sericho Kitale (! Merti East Province ! Marakwet Wamba ( (! Nginyang MT ELGON Endebess Moiben BARINGO S O M A L I A Kapsakwony Kimilili ISIOLO o T g LUGARI n AmagoroBUNGOMA Kabarti onjo UASIN GISHU r TESO ! a Garba Tula ( B Kabarnet (! . Busia MalavaEldoret KEIYO Baringo T (! Busia $+o (! L Don Dol $+BUSI(A! KAKAMEGA Chepkorio LAIKIPIA IsioloMERU NORTH (! BUTERE ! Rumuruti $+ MUMIAS (Kakamega L. Bogoria Maua (! (! Bukura NANDI KOIBATEK LugariSIAYA (! Meru Lower Juba (! (! VIHIGA Nyahururu Nanyuki (! SirisiaSiaya (! Ndaragwa (! T Dadaab KISUMU Kisumu Mogotio (! MERU CENTRAL ! NYANDO & BONDO ( Soghor T o Molo THARAKA Nakuru MERU SOUTH GARISSA AheroKERICHO (! NYANDARUA L. Victoria Mbita (! NAKURLU. Nakuru EMBU Chuka (! Kericho NYERI Nyeri Garissa SUBA RACHUONYO L. Elmentaita (! (! ! Nyandarua (! Kyuso ( M(!arani BURET (! KIRINYAG(!A Siakago $+ RangweC SUBAHOMA BAY E Gilgil N!NYAMIRASotik MURANGA MBEERE (T Embu MWINGI R Naivasha (! Suneka A Bomet L. Naivasha L Ndana(!i Ndhiwa GUCHA K MARAGUA IS BOMET Mwingi II MIGORI Thika Kavaini Migori Narok KIAMBU (! (! (! TRANS MARA Karuri THIKA Kwale Kathiani KURIA (! ! Mutitu Suna NAROK ( NA(I!ROBI Mwala Kitui IJARA Ngong (! %,ooMACHAKOS Hola Machakos $+ (! (! Ijara Mbooni KITUI L. Kwenia NunguniWote TANA RIVER Kajiado (! (! Mutomo Mara KAJIAD$+O MAKUENI Olengarua T LAMU Ziwa Shalu Garsen Lamu (! Kibwezi Witu Namanga Lake Amboseli T A N Z A N I A Rongai MALINDI Shinyanga Oloitokitok TAITA TAVETA Malindi Legend (! (! Taveta Wundanyi (! (! District town Mwatate Voi (! Provincial town L. -

East Africa Programme Quarterly Report (May – August 2017)

East Africa Programme Quarterly Report (May – August 2017) Background In mid-2016, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) opened an East Africa office, based in Nairobi, to better support giraffe conservation initiatives in the region by establishing a regional base. These efforts focus on collaborations with government institutions, private stakeholders, along with local and international NGOs. The East African region is critical for the long-term survival of wild populations of giraffe as it is home to three distinct species of giraffe: Masai giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi), reticulated giraffe (Giraffa reticulata) and Nubian giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis camelopardalis). This is the second Quarterly Report for 2017 and it highlights the programmes that GCF has initiated towards conserving the three giraffe species in the region. Broad-ranging programmes A recent genetic study by GCF and partners on giraffe taxonomy revealed that there are four distinct giraffe species with five subspecies. In order to further our understanding of the taxonomic findings of this initial study, GCF has partnered with the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre. Kenya is home to three of the four extant species of giraffe, however, it is unknown whether different species have interbred (hybridised) in their current and historical overlapping ranges. With our support KWS is currently collecting tissue biopsy samples from giraffe populations across the country. After analysis, these results will provide crucial information on the genetic diversity of giraffe populations in Kenya. Findings from this study will help inform conservation management practices since all three species are faced with varying threats. Thus far, KWS have collected 112 samples (59 male and 53 female) from across Nairobi National Park, Ngong Nature Reserve, Kigio Wildlife Conservancy, Soysambu Wildlife Conservancy, Hell’s Gate NP and surrounding farms, and Lake Nakuru National Park (Fig. -

Solio Lodge Certification Achieved

Name of the facility: Solio Lodge Certification achieved: Gold Year opened: 2010 Tourism region: Laikipia-Samburu County: Laikipia Province: Rift Valley District: Laikipia Location Notes: within Solio Ranch in Laikipia County Facility Solio lodge is located within Solio Ranch - a privately owned wildlife conservancy situated in Laikipia County, 22 kilometers North of Nyeri Town. The lodge is specifically located on Global Positioning System (GPS) Coordinates, Latitude: 000.15’4.512 S and Longitude: 360.52’43.776 E. It has 6 guest tents with a bed capacity of 12 visitors and a total work force of 30 employees. Solio Ranch is located on approximately 17,500 acres parcel of land and it is a protected area geared towards rhino conservation. The Ranch plays a major role in the protection and breeding black rhinos in Kenya. Its conservation and breeding program has been successful and provides stock for translocation to other sanctuaries, such as Nakuru, Tsavo and the Aberdares National Parks. The Ranch is also home to other wildlife, including buffalo, zebra, giraffe and plains game such as eland, oryx, impala, waterbuck, Thompson's gazelle and warthog. It is a haven for birdlife including grey-crowned cranes. Sustainable tourism measures Environmental Criteria Environmental management Solio lodge is steered by the Corporate Company’s- The Safari Collection - environmental policy. The document puts emphasis on continued improvement on sound and sustainable management practices, social responsibility, commitment to environmental protection and conservation of resources such as water energy, and waste management, and compliance to relevant government regulations and legislations. The lodge has undertaken its annual self-Environmental Audit (EA) as required by EMCA 1999 (Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act).