Traversing the East Coast in a Pair of Converse Laura A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Book Was First Published in 1951 by Little, Brown and Company

This book was first published in 1951 by Little, Brown and Company. THE CATCHER IN THE RYE By J.D. Salinger © 1951 CHAPTER 1 If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, an what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They're quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They're nice and all--I'm not saying that--but they're also touchy as hell. Besides, I'm not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I'll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy. I mean that's all I told D.B. about, and he's my brother and all. He's in Hollywood. That isn't too far from this crumby place, and he comes over and visits me practically every week end. He's going to drive me home when I go home next month maybe. He just got a Jaguar. One of those little English jobs that can do around two hundred miles an hour. -

EBCS AR Titles

EBCS AR Titles QUIZNO TITLE 41025EN The 100th Day of School 35821EN 100th Day Worries 661EN The 18th EmerGency 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea 11592EN 2095 8001EN 50 Below Zero 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins 413EN The 89th Kitten 80599EN A-10 Thunderbolt II 16201EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) 67750EN Abe Lincoln Goes to WashinGton 1837-1865 101EN Abel's Island 9751EN Abiyoyo 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows 13551EN Abraham Lincoln 866EN Abraham Lincoln 118278EN Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War 17651EN The Absent Author 21662EN The Absent-Minded Toad 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How I Visited Yellowstone... 17501EN Abuela 15175EN Abyssinian Cats (Checkerboard) 6001EN Ace: The Very Important PiG 35608EN The Acrobat and the AnGel 105906EN Across the Blue Pacific: A World War II Story 7201EN Across the Stream 1EN Adam of the Road 301EN Addie Across the Prairie 6101EN Addie Meets Max 13851EN Adios, Anna 135470EN Adrian Peterson 128373EN Adventure AccordinG to Humphrey 451EN The Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein 20251EN The Adventures of Captain Underpants 138969EN The Adventures of Nanny PiGGins 401EN The Adventures of Ratman 64111EN The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby 71944EN AfGhanistan (Countries in the News) 71813EN Africa 70797EN Africa (The Atlas of the Seven Continents) 13552EN African-American Holidays EBCS AR Titles 13001EN African Buffalo (African Animals Discovery) 15401EN African Elephants (Early Bird Nature) 14651EN Afternoon on the Amazon 83309EN Air: A Resource Our World Depends -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

1. What's in the Witch's Kitchen? (Early Years) 2. Where's Spot

1. What's in the Witch's Kitchen? (Early years) Author: Nick Sharratt ISBN: 9781406340075 Publisher: Walker Books Ltd Britain's most popular artist presents a brilliantly original format that very young children will delight in time and again. The witch has hidden a trick and a treat in her magical kitchen cupboards! 2. Where's Spot? (Early Years) Author: Eric Hill ISBN: 9780141343747 Publisher: Penguin Random House Children's UK In Spot's first adventure children can join in the search for the mischievous puppy by lifting the flaps on every page to see where he is hiding. The simple text and colourful pictures will engage a whole new generation of pre- readers as they lift the picture flaps in search of Spot. 3. Red Rockets and Rainbow Jelly? (Early Years) Author: Sue Heap ISBN: 9780141383385 Publisher: Penguin Random House Children's UK Sue and Nick are best friends who like lots of different things in lots of different colours. Here, they show us some of their favourite things from purple hair and all things blue to red cars and red dogs. The artwork is stunning with each artist contributing alternate pages in their own inimitable style. Read at Home English booklist 1 4. Fancy Dress Farmyard (Early Years) Author: Nick Sharratt ISBN: 9781407115917 Publisher: Scholastic There's a party at the farmyard, and it's going to be fancy dress. Children will love lifting the flaps to discover which animals are hiding behind the disguises. Pig has come as a pirate, Duck as a superhero and Sheep as a wizard. -

Fairy Tales and Rescue in Sandra Cisneros's the House on Mango Street

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2007 Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales and Rescue in Sandra Cisneros's the House on Mango Street Christina Marie Frank Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Frank, Christina Marie, "Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales and Rescue in Sandra Cisneros's the House on Mango Street" (2007). ETD Archive. 331. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/331 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDITED TITLE FOR THE THESIS OF CHRISTINA MARIE FRANK FAIRY TALES AND RESCUE IN CISNEROS’S THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET HAPPILY EVER AFTER: FAIRY TALES AND RESCUE IN SANDRA CISNEROS’S THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET CHRISTINA MARIE FRANK Bachelor of Science in Education Ohio University November, 2001 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December, 2007 This thesis has been approved For the Department of ENGLISH and the College of Graduate Studies by __________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Jeff Karem __________________________ Department & Date __________________________________________________________ Graduate Director, Dr. Jennifer Jeffers __________________________ Department & Date __________________________________________________________ Dr. Rachel Carnell __________________________ Department & Date HAPPILY EVER AFTER: FAIRY TALES AND RESCUE IN SANDRA CISNEROS’S THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET CHRISTINA MARIE FRANK ABSTRACT Within The House on Mango Street, Cisneros weaves several subtle literary allusions, mostly from fairy tales, into many of her vignettes. -

A Series of Unfortunate Events

A Teacher’s Guide to Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events www.lemonysnicket.com www.lemonysnicket.com A Teacher’s Guide to Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events Dear Educator, Teachers tend to be noble people, because there are few deeds nobler than interesting a young person in a good book. Even in the noblest of professions, however, there can be a few bad apples, an expression which here means “teachers who would rather interest their students in something unpleasant.” The books in A Series of Unfortunate Events, for instance, include man-eating leeches, large vocabulary words, and a talentless vice principal who subjects his students to six- hour violin recitals. In fact, the only thing worse for an impressionable young mind than a book in A Series of Unfortunate Events is an attractively packaged and inexpensively priced paperback book in A Series of Unfortunate Events. Unless you’re a bad apple, you’d be much better off folding this teaching guide into a paper airplane and sailing it straight out your classroom window. Wouldn’t you rather teach something else? With all due respect, www.lemonysnicket.com 1 About this Guide The activities in this guide are designed to capitalize on the oddly irresistible genius of Lemony Snicket. In addition to in-depth teaching plans for the first book of the series, The Bad Beginning, you will find extensive across-the-series activities that incorporate the details of Books 2 through 13. Activities can be used for independent readers, small groups, or full classes.Whether used in their entirety or in part, these activities will allow students to become more adept in understanding vocabulary, idioms, anagrams, word choice, character development, and thematic statements. -

Morgan Horse Magazine

The ^Morgan J£orse ^Magazine "His neigh is like the bidding of a monarch, and his countenance enforces homage." — KINO HENRY V. A QLJARTERLY MAGAZINE (Nov., Feb., May, Aug.) Office of Publication SOUTH WOODSTOCK, VERMONT VOL. V MAY 1946 NO. 3 469 MORGAN REGISTRATIONS IN 1945 COMMENT ON BLACK HAWK ARTICLE There was a 10 per cent increase in registrations recorded in CORNELIUS WHALEN the American Morgan Horse Register in 1945 over the year This writer differs sharply with some portions of the article 1944. In 1945 there were 469, as compared with 427 in 1944. by A. M. Hartung on Vermont Black Hawk 5, in the November 1945 represented a new high in this respect. In the fifteen-year issue of THE MORGAN HORSE MAGAZINE. The writer spe period, 1920 to 1934, inclusive, the average annual number of cifically differs with what Mr. Hartung says of the size and registrations recorded was 106. 19 34 showed the first real in weight of Sherman Morgan, the sire of Black Hawk, and em crease in breeding activity and 127 were registered in that year. phatically with his "Paddy Story," the oft repeated fable that a The number of registrations for the subsequent years have been horse other than Sherman Morgan was the sire of Black Hawk. as follows: Sherman Morgan did not stand 1 3' 4 and weigh less than 3 1935 126 850, as stated by Mr. Hartung, but stood 13 ,4 and weighed 1936 172 925, as stated, both in speech and writing by Mr. John Bellows, 1937 179 who owned Sherman Morgan from 1829, until his death at 1938 186 Lancaster, N. -

The Catcher in the Rye and Sandra Cisneros' the House on Mango Street

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jitka Modlitbová Youth and Society in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph. D. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‟s signature I would like to thank Mgr. Martina Horáková, PhD. for her patience, support and valuable advice. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Bildungsroman and Its Traces in the Works of Cisneros and Salinger 3 2.1. The Catcher in the Rye 5 2.2. The House on Mango Street 8 3. The Society versus the Self: Holden‟s and Esperanza‟s Coming of Age 12 3.1 Attitudes to Gender Roles and Stereotypes 12 3.2 Socio-economic Status 16 x x 3.3 Relationships with Parents and Siblings 20 3.4 Friends, Peers, Role Models 24 x 3.5 Perception of Love and Sex 29 3.6 Motives of Quest and Escape 33 33 4. Conclusion 37 Works Cited 39 Summary 43 Resumé 44 1. Introduction This thesis examines and compares The Catcher in the Rye (1951) by Jerome David Salinger and The House on Mango Street (1984) by Sandra Cisneros. On the first sight, these two pieces of literature seem utterly different: The Catcher in the Rye, set in the late forties, is a story told by Holden Caulfield, a depressed, alienated 16- year-old boy of upper-middle-class origin who strongly disapproves of the world around him and desperately tries to escape the falsity and arrogance that surrounds him. -

Conspiracy Narratives in Lemony Snicket's a Series Of

CONSPIRACY NARRATIVES IN LEMONY SNICKET’S A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS by © Jillian Hatch A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Memorial University of Newfoundland August 2015 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador ABSTRACT This thesis studies themes of conspiracy in children’s literature through the lens of Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events (ASOUE). The evolution of conspiracy theory, from traditional to postmodern, is mirrored in the journey of the Baudelaire children. Starting out as eager detectives, the children develop into survivors, keenly aware of humanity’s many flaws. Despite this dark, conspiracy-laden journey, ASOUE is remarkably enjoyable, largely due to the playfulness with which the theme of conspiracy is treated. The characters, Lemony Snicket (as character, narrator, and author), and the reader all partake in this conspiratorial playfulness; and these modes of play serve to entice the reader into active reading and learning. The themes of conspiracy and play within ASOUE provide the child reader with the tools needed to address and master linguistic challenges, to overcome anxieties, and to engage with our frequently scary and chaotic world by way of realistic optimism. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks are due to many people who have provided assistance, knowledge, support, and enduring patience during the long writing process. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor, Christopher Lockett, whose critical passion and insights enabled me to shape this material, and whose encouragement allowed me to reinvigorate a long-dormant project. Many thanks also to Danine Farquharson and Jennifer Lokash for their generous assistance, and to Andrew Loman and Naomi Hamer, whose advice and insights have been greatly appreciated. -

How Unfortunate

How Unfortunate... The Austere Academy by Lemony Snicket and Brett Helquist ISBN: 9780064408639 Binding: Hardback Series: A Series of Unfortunate Events Publisher: HarperCollins Pub. Date: 2000-08-08 Pages: 240 Price: $17.50 NOW A NETFLIX ORIGINAL SERIES As the three Baudelaire orphans warily approach their new home Prufrock Preparatory School, they can't help but notice the enormous stone arch bearing the school's motto Memento Mori or "Remember you will die." This is not a cheerful greeting and certainly marks an inauspicious beginning to a very bleak story just as we have come to expect from Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events, the deliciously morbid set of books that began with The Bad Beginning and only got worse. The Bad Beginning by Lemony Snicket and Brett Helquist ISBN: 9780064407663 Binding: Hardback Series: Series of Unfortunate Events Publisher: HarperCollins Pub. Date: 1999-08-25 Pages: 176 Price: $17.50 Dear Reader, I'm sorry to say that the book you are holding in your hands is extremely unpleasant. It tells an unhappy tale about three very unlucky children. Even though they are charming and clever, the Baudelaire siblings lead lives filled with misery and woe. From the very first page of this book when the children are at the beach and receive terrible news, continuing on through the entire story, disaster lurks at their heels. One might say they are magnets for misfortune.In this short book alone, the three youngsters encounter a greedy and repulsive villain, itchy clothing, a disastrous fire, a plot to steal their fortune, and cold porridge for breakfast.It is my sad duty to write down these unpleasant tales, but there is nothing stopping you from putting this book down at once and reading something happy, if you prefer that sort of thing.With all due respect,Lemony Snicket The Bad Beginning Or, Orphans! by Lemony Snicket and Brett Helquist ISBN: 9780061146305 Binding: Paperback Series: A Series of Unfortunate Events Publisher: HarperCollins Pub. -

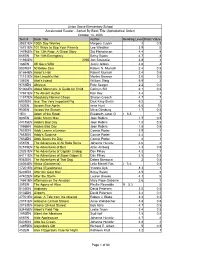

Test # Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 35821EN 100Th

Union Grove Elementary School Accelerated Reader - Sorted By Book Title (Alphabetical Order) October 14, 2003 Test # Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3 0.5 18751EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5 14796EN The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman 4.4 4 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 3.8 1 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 8001EN 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch 2.4 0.5 51654EN Aaron's Hair Robert Munsch 2.4 0.5 11151EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 9751EN Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 51006EN About Mammals: A Guide for Child Cathryn Sill 2.1 0.5 17651EN The Absent Author Ron Roy 3.4 1 11577EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 6001EN Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10 950EN Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg 1.7 0.5 1EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet G r 6.5 9 983EN Addie Meets Max Joan Robins 1.7 0.5 44185EN Addie's Bad Day Joan Robins 1.8 0.5 1065EN Addies Bad Day Joan Robins 1.8 0.5 7651EN Addy Learns a Lesson Connie Porter 3.9 1 7653EN Addy's Surprise Connie Porter 4.4 1 7652EN Addy Saves the Day Connie Porter 4 1 451EN The Adventures of Ali Baba Berns Johanna Hurwitz 4.6 2 52579EN The Adventures of Bert Allan Ahlberg 1.3 0.5 20251EN The Adventures of Captain Underp Dav Pilkey 4.3 1 64111EN The Adventures of Super Diaper B Dav Pilkey 2.5 0.5 9562EN The Adventures of Taxi Dog Debra Barracca 3 0.5 46024EN Africa (Continents) Leila Merrell Fos t 3.6 0.5 17201EN Africa (Eyewitness) Yvonne Ayo 8.3 1 5201EN After the Goat Man Betsy Byars 4.5 3 47402EN After the Storm Lauren Brooke 4.3 5 14651EN Afternoon on the Amazon Mary Pope Osborne 2.6 1 201EN The Agony of Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 5.3 5 5101EN Airplanes David Petersen 3.2 0.5 5102EN Airports David Petersen 3.4 0.5 27701EN Akiak: A Tale from the Iditarod Robert J. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2007

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2007 Juvenile Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Compact Discs 100 - Philosophy & Psychology DVD Videos/Videocassettes 200 - Religion E Audiocassettes 300 - Social Sciences E Audiovisual Materials 400 - Language E Books 500 - Science E CD-ROMs 600 - Technology E Compact Discs 700 - Art E DVD Videos/Videocassettes 800 - Literature E Foreign Language 900 - Geography & History E New Additions Audiocassettes Fiction Audiovisual Materials Foreign Languages Biographies Graphic Novels CD-ROMs Large Print Fiction Call # Author Title J FIC/CARSLON Carlson, Drew. Attack of the Turtle J FIC/CUMMINGS 3-4 Cummings, Mary Three names of me J FIC/DANZIGER 3-4 Danziger, Paula Amber Brown wants extra credit J FIC/KELLY 3-4 Kelly, Katy Lucy Rose J FIC/KRULIK 3-4 Krulik, Nancy E. Any way you slice it J FIC/KRULIK 3-4 Krulik, Nancy E. Girls don't have cooties J FIC/KRULIK 3-4 Krulik, Nancy E. I hate rules! J FIC/KRULIK 3-4 Krulik, Nancy E. Quiet on the set! J FIC/LAIKEN Laiken, Deidre S. The wizard of Oz J FIC/LEVINE Levine, Gail Carson. Fairy dust and the quest for the egg J FIC/MCMULLAN 3-4 McMullan, Kate. Help! It's parents day at DSA J FIC/OGDEN Ogden, Charles. Rare beasts J FIC/OSBORNE Osborne, Mary Pope. Night of the new magicians J FIC/ROWLING Rowling, J. K. Harry Potter and the chamber of secrets J FIC/ROWLING Rowling, J. K. Harry Potter and the goblet of fire J FIC/ROWLING Rowling, J. K. Harry Potter and the prisoner of Azkaban J FIC/ROWLING Rowling, J.