Preserving and Creating Culture the Gullah-Geechee People Keith W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 2-10-2009 The Atlantic Mind: Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World Mark J. Fleszar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Fleszar, Mark J., "The Atlantic Mind: Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ATLANTIC MIND: ZEPHANIAH KINGSLEY, SLAVERY, AND THE POLITICS OF RACE IN THE ATLANTIC WORLD by MARK J. FLESZAR Under the Direction of Dr. Jared Poley and Dr. H. Robert Baker ABSTRACT Enlightenment philosophers had long feared the effects of crisscrossing boundaries, both real and imagined. Such fears were based on what they considered a brutal ocean space frequented by protean shape-shifters with a dogma of ruthless exploitation and profit. This intellectual study outlines the formation and fragmentation of a fluctuating worldview as experienced through the circum-Atlantic life and travels of merchant, slaveowner, and slave trader Zephaniah Kingsley during the Era of Revolution. It argues that the process began from experiencing the costs of loyalty to the idea of the British Crown and was tempered by the pervasiveness of violence, mobility, anxiety, and adaptation found in the booming Atlantic markets of the Caribbean during the Haitian Revolution. -

Mack Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 472 SO 024 893 AUTHOR Botsch, Carol Sears; And Others TITLE African-Americans and the Palmetto State. INSTITUTION South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 246p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Black Culture; *Black History; Blacks; *Mack Studies; Cultural Context; Ethnic Studies; Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Local History; Resource Materials; Social Environment' *Social History; Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; South Carolina ABSTRACT This book is part of a series of materials and aids for instruction in black history produced by the State Department of Education in compliance with the Education Improvement Act of 1984. It is designed for use by eighth grade teachers of South Carolina history as a supplement to aid in the instruction of cultural, political, and economic contributions of African-Americans to South Carolina History. Teachers and students studying the history of the state are provided information about a part of the citizenry that has been excluded historically. The book can also be used as a resource for Social Studies, English and Elementary Education. The volume's contents include:(1) "Passage";(2) "The Creation of Early South Carolina"; (3) "Resistance to Enslavement";(4) "Free African-Americans in Early South Carolina";(5) "Early African-American Arts";(6) "The Civil War";(7) "Reconstruction"; (8) "Life After Reconstruction";(9) "Religion"; (10) "Literature"; (11) "Music, Dance and the Performing Arts";(12) "Visual Arts and Crafts";(13) "Military Service";(14) "Civil Rights"; (15) "African-Americans and South Carolina Today"; and (16) "Conclusion: What is South Carolina?" Appendices contain lists of African-American state senators and congressmen. -

Works Like a Charm: the Occult Resistance of Nineteenth-Century American Literature

WORKS LIKE A CHARM: THE OCCULT RESISTANCE OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE by Noelle Victoria Dubay A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2020 Abstract Works like a Charm: The Occult Resistance of Nineteenth-Century American Literature finds that the question of whether power could work by occult means—whether magic was real, in other words—was intimately tied, in post-Revolutionary America, to the looming specter of slave revolt. Through an examination of a variety of materials—trial narratives, slave codes, novels and short stories, pamphlets, popular occult ephemera—I argue that U.S. planters and abolitionists alike were animated by reports that spiritual leaders boasting supernatural power headed major rebellions across the Caribbean, most notably in British-ruled Jamaica and French-ruled Saint-Domingue. If, in William Wells Brown’s words, the conjurer or root-doctor of the southern plantation had the power to live as though he was “his own master,” might the same power be capable of toppling slavery’s regimes altogether? This question crossed political lines, as proslavery lawmakers and magistrates as well as antislavery activists sought to describe, manage, and appropriate the threat posed by black conjuration without affirming its claims to supernatural power. Works like a Charm thus situates the U.S. alongside other Atlantic sites of what I call “occult resistance”—a deliberately ambivalent phrase meant to register both the documented use of occult practices to resist slavery and the plantocracy’s resistance to the viability of countervailing powers occulted (i.e., hidden) from their regimes of knowledge—at the same time as it argues that anxiety over African-derived insurrectionary practices was a key factor in the supposed secularization of the West. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

FORMER MEMBERS H 1870–1887 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Robert Smalls 1839 –1915 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 1875–1879; 1882–1883; 1884–1887 REPUBLICAN FROM SOUTH CAROLINA n escaped slave and a Civil War hero, Robert Smalls publication of his name and former enslaved status in A served five terms in the U.S. House, representing northern propaganda proved demoralizing for the South.7 a South Carolina district described as a “black paradise” Smalls spent the remainder of the war balancing his role because of its abundant political opportunities for as a spokesperson for African Americans with his service freedmen.1 Overcoming the state Democratic Party’s in the Union Armed Forces. Piloting both the Planter, repeated attempts to remove that “blemish” from its goal which was re-outfitted as a troop transport, and later the of white supremacy, Smalls endured violent elections and a ironclad Keokuk, Smalls used his intimate knowledge of the short jail term to achieve internal improvements for coastal South Carolina Sea Islands to advance the Union military South Carolina and to fight for his black constituents in the campaign in nearly 17 engagements.8 face of growing disfranchisement. “My race needs no special Smalls’s public career began during the war. He joined defense, for the past history of them in this country proves free black delegates to the 1864 Republican National them to be equal of any people anywhere,” Smalls asserted. Convention, the first of seven total conventions he “All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”2 attended as a delegate.9 While awaiting repairs to the Robert Smalls was born a slave on April 5, 1839, in Planter, Smalls was removed from an all-white streetcar Beaufort, South Carolina. -

The Emergence of the Gullah: Thriving Through 'Them Dark Days'

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Summer 2015 The meE rgence of the Gullah: Thriving Through ‘Them Dark Days’ Brian Coxe John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the African History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Coxe, Brian, "The meE rgence of the Gullah: Thriving Through ‘Them Dark Days’" (2015). Masters Essays. 19. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/19 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence of the Gullah: Thriving Through ‘Them Dark Days’ An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Brian Coxe 2015 Spanish moss clings to the branches of oak trees south of the sand hills which run the width of South Carolina from Aiken to Chesterfield County separating what is known as the “Up” and the “Low” Country of this region. The geographic barrier of the Sandhills created two distinct regions with vastly different climates. The Low Country’s sub tropical climate left it nearly uninhabitable in many places due to malarial swamps, with Charleston as the exception. The city of Charleston became a major commercial hub and one of the most populated cities in America during the antebellum era. -

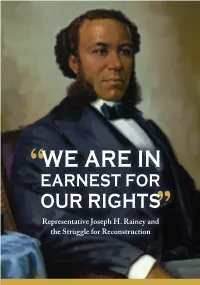

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

16Goodreads the History Book Club

29/04/2015 Goodreads | The History Book Club AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (showing 143 of 43) Title / Author / ISBN Home My Books Groups Recommendations Explore The History Book Club discussion AMERICAN GOVERNMENT > HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 208 views The History Book Club Comments (showing 143 of 43) (43 new) post a comment » date newest » message 1: by Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief (new) May 26, 2011 08:12PM Group Home Events Invite People This is a thread which can be used to discuss the House of Representatives. Bookshelf Photos Members Discussions Videos Polls flag * message 2: by Alisa (last edited Aug 05, 2013 01:50PM) (new) May 26, 2011 09:03PM search discussion posts search I recently purchased this book and am looking forward to reading it. unread topics | mark unread Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen Primeiro apê Conquiste seu sonho by Philip Dray com a MRV. Mensais a Synopsis: partir de 299. Simule. Reconstruction was a time of idealism and sweeping change, as the victorious Union created citizenship rights for the freed slaves and granted the vote to black men. Sixteen black Southerners, elected to the U.S. Congress, arrived in Washington to advocate reforms such as public education, equal rights, land distribution, and the suppression of the Ku Klux Klan. But these men faced astounding odds. They were belittled as corrupt and inadequate by their white political opponents, who used legislative trickery, libel, bribery, and the brutal intimidation of their constituents to rob them of their base of support. -

Use of Copula and Auxiliary BE by African American Children With

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 Use of Copula and Auxiliary BE by African American Children with Gullah/Geechee Heritage Jessica Richardson Berry Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Sciences and Disorders Commons Recommended Citation Berry, Jessica Richardson, "Use of Copula and Auxiliary BE by African American Children with Gullah/Geechee Heritage" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3513. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3513 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. USE OF COPULA AND AUXILIARY BE BY AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN WITH GULLAH/GEECHEE HERITAGE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders by Jessica Richardson Berry B.A., Winthrop University, 2008 M.A., SC State University, 2010 May 2015 This dissertation is dedicated to my parents Don and Sharon Richardson, who have supported me unconditionally. You told me that I could do anything and I believed you. This is also dedicated to my angels who look down on me daily and smile with the love of God. I’m sad that you had to leave but I know that you are always with me. -

Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950

Moore 1 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950 By Alex Moore Project Advisor: Dyane Harvey Senior Global Studies Thesis with Honors Distinction December 2010 [We] need to understand that African slaves, through largely self‐generative activity, molded their new environment at least as much as they were molded by it. …African Americans are descendants of a people who were second to none in laying the foundations of the economic and cultural life of the nation. …Therefore, …honest American history is inextricably tied to African American history, and…neither can be complete without a full consideration of the other. ‐‐Sterling Stuckey Moore 2 Index 1) Finding the Familiar and Expressions of Resistance in Plantation Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 6 a) The Ring Shout b) The Cake Walk 2) Experimentation and Responding to Hostility in Early Partner Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 14 a) Hugging Dances b) Slave Balls and Race Improvement c) The Blues and the Role of the Jook 3) Crossing the Racial Divide to Find Uniquely American Forms in Swing Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐ 22 a) The Charleston b) The Lindy Hop Topics for Further Study ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 30 Acknowledgements ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 31 Works Cited ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 32 Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Appendix D Moore 3 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance When people leave the society into which they were born (whether by choice or by force), they bring as much of their culture as they are able with them. Culture serves as an extension of identity. Dance is one of the cultural elements easiest to bring along; it is one of the most mobile elements of culture, tucked away in the muscle memory of our bodies. -

Implications of a Feminist Narratology: Temporality, Focalization and Voice in the Films of Julie Dash, Mona Smith and Trinh T

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 11-4-1996 Implications of a Feminist Narratology: Temporality, Focalization and Voice in the Films of Julie Dash, Mona Smith and Trinh T. Minh-ha Jennifer Alyce Machiorlatti Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Machiorlatti, Jennifer Alyce, "Implications of a Feminist Narratology: Temporality, Focalization and Voice in the Films of Julie Dash, Mona Smith and Trinh T. Minh-ha" (1996). Wayne State University Dissertations. 1674. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1674 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. IMPLICATIONS OF A FEMINIST NARRATOLOGY: TEMPORALITY, FOCALIZATION AND VOICE IN THE FILMS OF JULIE DASH, MONA SMITH AND TRINH T. MINH-HA Volume I by JENNIFER ALYCE MACHIORLATTI DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 1996 MAJOR: COMMUNICATION (Radio/Television/Film) Approved by- © COPYRIGHT BY JENNIFER ALYCE MACHIORLATTI 1996 All Rights Reserved her supportive feminist perspective as well as information from the speech communication and rhetorical criticism area of inquiry. Robert Steele approached this text from a filmmaker's point of view. I also thank Matthew Seegar for guidance in the graduate program at Wayne State University and to Mark McPhail whose limited presence in my life allowed me consider the possibilities of thinking in new ways, practicing academic activism and explore endless creative endeavors. -

GULLAH GEECHEE SUMMER SCHOOL South Carolina, Georgia and Florida — PART I: Origins and Early Development | June 6, 2018 from Pender County, North Carolina, to St

7/8/2018 + The Corridor is a federal National Heritage Area and it was established by Congress to recognize the unique culture of the Gullah Geechee people who have traditionally resided in the coastal areas and the sea islands of North Carolina, GULLAH GEECHEE SUMMER SCHOOL South Carolina, Georgia and Florida — PART I: Origins and Early Development | June 6, 2018 from Pender County, North Carolina, to St. Johns County, Florida. © 2018 Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission Do not reproduce without permission. + + Overview Overview “Gullah” or “Geechee”: Etymologies and Conventions West African Origins of Gullah Geechee Ancestors First Contact: Native Americans, Africans and Europeans Transatlantic Slave Trade through Charleston and Savannah Organization of Spanish Florida + England’s North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia Colonies The Atlantic Rice Coast Charter Generation of Africans in the Low Country Incubation of Gullah Geechee Creole Culture in the Sea Colonies Islands and Coastal Plantations ©Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission | Do not reproduce without permission. ©Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission | Do not reproduce without permission. + + “Gullah” or “Geechee”? “Gullah” or “Geechee”? Scholars are not in agreement as to the origins of the terms “Although Gullah and Geechee — terms whose “Gullah” and “Geechee.” origins have been much debated and may trace to specific African tribes or words — are often Gullah people are historically those located in coastal South used interchangeably these days, Mrs. [Cornelia Carolina and Geechee people are those who live along the Walker] Bailey always stressed that she was Georgia coast and into Florida. Geechee. And, specifically, Saltwater Geechee (as opposed to the Freshwater Geechee, who Geechee people in Georgia refer to themselves as “Freshwater lived 30 miles inland).