Tactical Urbanism in San Francisco: a Critical Planning Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alejandra Garcia Project Coordinator

City Council Report City Council Meeting: November 1, 2016 Agenda Item: 3.D To: Mayor and City Council From: David Martin, Director, Planning and Community Development, Strategic & Transportation Planning Subject: Safe Routes to School Program Encouragement & Education Contract Award Recommended Action Staff recommends that the City Council: 1. Award RFP #88 to Alta Planning + Design, Inc., a Los Angeles based company for grant-funded Safe Routes to School Program Encouragement and Education; and 2. Authorize the City Manager to negotiate and execute an agreement with Alta Planning + Design, Inc. in an amount not to exceed $450,000 over a 2-year period, with future year funding contingent on Council budget approval. Executive Summary The City of Santa Monica aims to expand the reach of the Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program by providing a series of encouragement and education activities to five elementary schools: John Muir Elementary School, Santa Monica Alternative Schoolhouse (SMASH), Franklin Elementary School, McKinley Elementary School, and Edison Language Academy. These schools were not included in the City’s initial 2012- 2013 SRTS Pilot program. Encouragement and Education programs catalyze desired outcomes around walking and biking behavior, and complement physical changes in the public right-of-way. This project is designed to provide “shelf ready” products and tools that can be easily used to educate students and inform parents about walking and biking to school. It will continue successful encouragement programs like Kidical Mass and Bike It! Walk It!, and complete walking and biking assessments at each school campus. Efforts include strengthening the relationship with student families to help ensure program sustainability. -

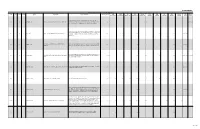

Attachment 2 ATP FY 2021Q2

ATTACHMENT 2 Active Transportation Program - Non-SB1 Project List PAED PS&E RW CON CON-NI PAED PS&E RW CON CON-NI CON CON-NI PPNO Cycle County District Agency Project Name Project Description Total Project Cost Programmed Programmed Programmed Programmed Programmed Allocated Allocated Allocated Allocated Allocated Award Award The proposed Active Transportation Plan ATP and SRTS Plan within the City 4901 1 LA 7 Inglewood, City of Active Transportation Plan and Safe Routes to School Plan boundaries, and will incorporate bicycle, pedestrian, ADA considerations and $ 486 $ - $ - $ - $ - $ 486 $ - $ - $ - $ - $ 486 09/29/2015 SRTS analysis of 8 of the 17 Inglewood Unified School District school sites. In the City of Indio - Surrounding Andrew Jackson ES - Pedestrian Infrastructure Improvements - Installation of new sidewalks including curb ramps and driveways 1144 1 RIV 8 Indio, City of Andrew Jackson Elementary Pedestrian Improvements $ 2,581 $ 21 $ 186 $ - $ 2,374 $ - $ 21 $ 186 $ - $ 2,374 $ - 05/02/2018 approaches, installation of enhanced crosswalks with bulb-outs, and speed feedback signs. Oak Parkway Trail Under Crossing and Johnny Cash Trail Construct a grade separated crossing of Natoma Street and connecting the Oak 1683 1 SAC 3 Folsom, City of $ 1,121 $ 35 $ 75 $ - $ 882 $ - $ 35 $ 75 $ - $ 882 $ - 07/24/2018 Connection Parkway Trail with both the Johnny Cash and Historic Powerhouse Canal Trails. A road diet and improve existing asphalt pathway. Replace approximately 4,000 Foster Road Side Panel Safe Routes to School Improvement 4935 1 LA 7 Norwalk, City of linear feet of 60 year old uneven, cracked and root buckled side panels, along $ 2,208 $ - $ 100 $ - $ 2,078 $ 30 $ - $ 100 $ - $ 2,078 $ 30 10/03/2017 10/03/2017 Project with 94 large bottle brush trees. -

2012 San Francisco State of Cycling Report

2012 San Francisco State of Cycling Report SFMTA | Municipal Transportation Agency Page 1 Edwin M. Lee | Mayor San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency City and County of San Francisco Board of Supervisors The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) is responsible for the planning, implementation, regulation, John Avalos | District 11 maintenance and operation of the multimodal transportation system in the City and County of San Francisco. The city’s David Campos | District 9 transportation system includes public transit, paratransit, streets, bicycle and pedestrian facilities, parking, signals, traffic controls, David Chiu | District 3 and taxi services. Carmen Chu | District 4 Malia Cohen | District 10 Board of Directors Tom Nolan | Chairman Sean Elsbernd | District 7 Jerry Lee | Vice-Chairman Mark Farrell | District 2 Leona Bridges Jane Kim | District 6 Cheryl Brinkman Eric Mar | District 1 Malcolm Heinicke Christina Olague | District 5 Joél Ramos Scott Wiener | District 8 Cristina Rubke Director of Transportation Edward Reiskin SFMTA Sustainable Streets Staff Peter Brown, State of Cycling Project Manager Matt Lasky, Co-Author Bond Yee Timothy Papandreou Darton Ito Anne Fritzler Bridget Smith Seleta Reynolds Craig Raphael Survey Consultant Corey, Canapary & Galanis This report is made possible by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority through a grant of Proposition K Local Transportation Sales Tax Funds. Page 2 Executive Summary The City and County of San Francisco is a national leader in The SFMTA’s 2012 State of Cycling Report benchmarks bicycle bicycle ridership, innovative cycling infrastructure, greenhouse gas volumes, bicycle safety and opinions about bicycle riding in San reductions and active living. Cities around the world are investing Francisco. -

Cycles of Investment: Bicycle Infrastructure, Gentrification, and the Restructuring of the San Francisco Bay Area

Environment and Planning A 2015, volume 47, pages 121 – 137 doi:10.1068/a130098p Cycles of investment: bicycle infrastructure, gentrification, and the restructuring of the San Francisco Bay Area John Stehlin Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, 507 McCone Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; e-mail [email protected] Received 16 July 2013; in revised form 11 July 2014 Abstract. Bicycling for transportation in American cities has grown dramatically in the past twenty years, symbolizing the return of capital investment and commercial vitality to formerly disinvested urban cores. The cycling ‘renaissance’ taking place to the greatest extent in gentrifying neighborhoods has been noted, but the processes relating cycling and gentrification have gone largely unexplored. This paper examines the early role that bicycle advocacy organizations in San Francisco played in articulating the specifically economic value of bicycle infrastructure investment. This narrative is now commonplace, and widely applied both to neighborhood revitalization and urban competition for ‘talent’. This alliance of bicycle advocacy with the ‘livable’ turn of gentrification raises serious questions for those who would pursue a more democratic and socially just politics of the bicycle. Keywords: cycling, gentrification, livability, infrastructure, San Francisco Introduction In recent years the bicycle has become an important symbol of the revitalization and ‘greening’ of American cities. San Francisco, birthplace of Critical Mass, enjoys a leadership role in this movement. While cycling in San Francisco remains in no sense dominant, 3.5% of residents commute to work by bike, and the city is steadily expanding and integrating its bicycle network in a push to reach a goal of 20% of all trips (work and nonwork) by bicycle by 2020. -

Adaptive-Bikeshare-Pilot-Launches-In-San Francisco

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SAN FRANCISCO, CA - Bike Share Program for People with Disabilities Launches in San Francisco. Launch and Media Ceremony – Try the adaptive cycles and talk to riders. Thursday, 7/25 12:00 Noon McLaren Lodge, Golden Gate Park 501 Stanyon St. San Francisco, CA Bay Wheels and BORP Adaptive Sports are thrilled to announce that handcycles and trikes for people with disabilities will, for the first time, be available on a regular schedule for use in San Francisco. We are especially excited to offer these adaptive cycles in Golden Gate Park during the weekly Sunday street closures when the park’s roads are transformed into a community celebration of mobility. The program will include handcycles, adaptive trikes, and a side-by-side tandem bike. Staff from BORP, the region’s leading provider of accessible recreation and adaptive sports for people with mobility-related disabilities, will be on-hand to fit, train, and assist riders on how to use the adaptive cycles. The program will run on Sundays in Golden Gate Park from 11 am – 4 pm, starting 7/28 and on Thursdays on the Embarcadero Waterfront soon after. “We’re thrilled to work with BORP to open up new possibilities for people with disabilities who want access to cycling in San Francisco,” said Caroline Samponaro, Head of Bike, Pedestrian and Scooter Policy at Lyft. “This program will allow us to learn more about the specific needs of the disability community and work closely with them, as well as our bike share partners at the City of San Francisco and MTC.” “San Francisco is an amazing city for cycling and Golden Gate Park on Sundays an incredible community event. -

2008 SF State of Cycling Report

2008 SAN FRANCISCO State of Cycling Report 2008 SAN FRANCISCO State of Cycling Report Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 Purpose of the State of Cycling Report 3 History of the State of Cycling Report 3 Bicycle Counts 4 Purpose 4 How the Counts Were Conducted 5 Results 7 Bicycle Survey 8 Purpose 8 How the Survey Was Conducted 9 Results 19 Improving Bicycling in San Francisco 20 Rating Bicycling in San Francisco 21 Recommendations 22 Plans for Future Reports List of Figures 4 Figure 1. Bicycle Count Locations 6 Figure 2. San Francisco Bicycle Counts 2006-2008 8 Figure 3. Intercept Survey Locations 9 Figure 4. Measures of Bicycle Ridership in San Francisco 9 Figure 5. Proportion of Frequent Cyclists to Infrequent Cyclists in San Francisco 10 Figure 6. Trip Purpose as a Percentage of All Trips Made in a Day 11 Figure 7. Cyclists’ Motivation to Ride 12 Figure 8. Reported Gender of Frequent vs. Infrequent Cyclists 13 Figure 9. Ratings of Barriers to Bicycling 14 Figure 10. Percentage of Respondents who Identifie d E a c h B a r r i e r a s a H i n d r a n c e t o Bicycling 1 5 F i g u r e 1 1 . F r e q u e n t a n d I n f r e q u e n t C y c l i s t s ’ F a m i l i a r i t y w i t h S a n F r a n c i s c o ’ s B i c y c l i n g Resources 16 Figure 12. -

Center for Advanced Multimodal Mobility Solutions and Education EVALUATING the POTENTIAL USE of CROWDSOURCED BICYCLE DATA IN

Center for Advanced Multimodal Mobility Solutions and Education Project ID: 2018 Project 03 EVALUATING THE POTENTIAL USE OF CROWDSOURCED BICYCLE DATA IN NORTH CAROLINA Final Report by Wei Fan (ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9815-710X) Zijing Lin (ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6529-5725) Wei Fan, Ph.D., P.E. Director, USDOT CAMMSE University Transportation Center Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The University of North Carolina at Charlotte EPIC Building, Room 3261, 9201 University City Blvd, Charlotte, NC 28223 Phone: 1-704-687-1222; Email: [email protected] for Center for Advanced Multimodal Mobility Solutions and Education (CAMMSE @ UNC Charlotte) The University of North Carolina at Charlotte 9201 University City Blvd Charlotte, NC 28223 September 2019 i ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was funded by the Center for Advanced Multimodal Mobility Solutions and Education (CAMMSE @ UNC Charlotte), one of the Tier I University Transportation Centers that were selected in this nationwide competition, by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), U.S. Department of Transportation (US DOT), under the FAST Act. The authors are also very grateful for all of the time and effort spent by DOT and industry professionals to provide project information that was critical for the successful completion of this study. DISCLAIMER The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are solely responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the material and information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation University Transportation Centers Program in the interest of information exchange. -

Thesis Title Goes Here

Contested Streets: A Case Study Approach to Understanding Bicycle and Car Politics in Toronto, Canada by Jennifer Tannis Hill A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Geography and Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Jennifer Hill 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-68360-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-68360-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

C a T a L O G

EDDY MERCKX CYCLES CATALOGUE 201 1 JOIN THE CANNIBAL COMMUNITY ON www.eddymerckx.com CATALOGUE 201 1 ISSUE 01 > 2011 NEW EMX-7 Tom Boonen and Eddy Merckx put the ultimate racing bike to the test BRAVE NEW WORLD OF BIKE DESIGN Cycling follows in the footsteps of Formula 1 and the aerospace industry URBAN BIKE PROJECT What would an Eddy Merckx Urban Bike look like? 5 EMX-7 Quick Step - Airfoil shaped seatpost design 3 The Eddy Merckx Cycles company has come a long way in its 30 year history - and the last few years have seen an acceleration of that change. A new team is on hand to translate my beliefs and dreams into a bigger reality. The new EMX-7 is a classic example. It uses advanced carbon fiber technology to produce the strongest, stiffest yet lightest racing bike of them all. When you ride one, you know you have the best - bar none. You’ll be fitted by one of our expert technicians so that it is precisely adapted to your size and weight. It’s the bike that Tom Boonen and the Quick Step Team will be using next year, day in, day out, for every race and training session. It’s the illustration of what Eddy Merckx Cycles does best - namely producing the best engi- neered and best produced racing cycle on the planet. There is a new range of “Urban Bikes” inspired by the World-Hour-Record bike that I rode in 1972. Light, strong and very fast - they are based on a traditional look and feel: simple gearing, integrated wiring and in-built lights for safe and secure city riding. -

Bicycle Friendly America

BICYCLE2O1O FRIENDLY AMERICA TABLE OF CONTENTS BICYCLE FRIENDLY AMERICA ........2 Beaverton, OR ............................. 33 Santa Monica, CA ........................ 48 RDG Planning & Design ............... 68 Billings, MT .................................. 33 Schaumburg, IL ............................ 48 REI Lincoln Park ........................... 68 BICYCLE FRIENDLY STATES ............5 Bloomington, IN .......................... 34 Shawnee, KS ................................ 48 REI Northbrook, IL ...................... 69 Washington ........................................6 Boca Raton, FL ............................. 34 Sioux Falls, SD .............................. 49 San Francisco Landscapes ............69 Wisconsin .................................... 6 Brentwood, CA ............................ 34 Sitka, AK .......................................49 Saturno Design ............................ 70 Arizona ................................................7 Brunswick, ME ............................. 34 Sonoma, CA ................................. 49 Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. .......... 70 Minnesota ..........................................7 Burlington, VT ..............................35 South Lake Tahoe, CA .................. 49 The Hawley Company ................. 71 South Sioux City, NE..................... 50 PLATINUM COMMUNITIES Calistoga, CA ................................ 35 Toole Design Group LLC ............... 71 Spartanburg, SC ........................... 50 Boulder, CO .........................................8 -

Bicycling Renaissance in North America? Recent Trends and Alternative Policies to Promote Bicycling

Bicycling renaissance in North America? Recent trends and alternative policies to promote bicycling John Puchera, Charles Komanoffb, Paul Schimekc aDepartment of Urban Planning, Rutgers University, 33 Livingston Avenue, Suite 302, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-1900, USA, [email protected] bKomanoff Energy Associates, 636 Broadway, Suite 602, New York, New York 10012, USA [email protected] cVolpe National Transportation Systems Center, DTS-49, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA [email protected] This article appears in Transportation Research Part A, Vol. 33, Nos. 7/8, 1999, pp. 625-654, published by Pergamon © 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. It is one of ten articles appearing in a special double issue of Transportation Research A (September/November 1999) devoted to transport policy in an international perspective. Following is the table of contents: Transportation trends, problems, and policies: an international perspective. J Pucher External costs of intercity truck freight transportation. D Forkenbrock. Cars and clean air: a reappraisal. D Pickrell The trouble with minimum parking requirements. DC Shoup Demand management as an element of transportation policy: using carrots and sticks to influence travel behavior. MD Meyer Secrets of success: assessing the large increases in transit ridership achieved by Houston and San Diego transit providers. JF Kain, Z Liu Bicycling renaissance in North America? Recent trends and alternative policies to promote bicycling. J Pucher, C Komanoff, P Schimek Transformation of transport policy in Great Britain. P Goodwin Urban mobility in the developing world. R Gakenheimer Patterns of automobile dependence in cities: an international overview of key physical and economic dimensions with some implications for urban policy. -

Building the Embikeadero Waterfront Bike Path

building the emBIKEadero waterfront bike path a master plan + design toolkit for remaking the Embarcadero waterfront for all modes of transportation table of contents The Piero N. Patri Fellowship in Urban Design 4 introduction 6 project goals create big and small connections 8 create a true multi-modal boulevard 10 create a premier bike path for san francisco’s waterfront 11 overview cycling in san francisco 14 stakeholders 15 site analysis san francisco bicycle network 17 existing embarcadero facilities promenade 18 bike lanes 20 building the emBIKEadero waterfront path 22 master plan + design toolkit mid-block design + prototypes two travel lanes + bike lane + parking lane 24 two travel lanes + bike lane 26 three travel lanes + bike lane + parking lane 28 three travel lanes + bike lane 30 special condition: rincon park 32 special condition: third-street bridge 34 intersection design + prototypes loading zones 36 driveways intersections 37 signalized intersections 38 parking: back-in angled parking 40 conclusion 42 appendix a: precedents 44 appendix b: alternative proposals 46 appendix c: references + acknowledgements 48 the Piero N. Patri fellowship in urban design life to his work and the improvement of the city. Piero was the first chairman of the SPUR Environmental Design Committee, at SPUR and in 1961 was the principal author, along with a team including his brothers Remo and Tito, of one of SPUR’s first community plans: the Montgomery Center Plan, a visionary scheme that rethought the interconnection of the Financial District to the city, and which resulted, in a different form, in the ultimate siting of the Transamerica Pyramid.