Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'antonio, Michael Senior Thesis.Pdf

Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in History with Distinction Spring 2016 © 2016 Michael D’Antonio All Rights Reserved Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. James Brophy Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. David Shearer Committee member from the Department of History Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Barbara Settles Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This senior thesis would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr. James Brophy of the University of Delaware history department. His guidance in research, focused critique, and continued encouragement were instrumental in the project’s formation and completion. The University of Delaware Office of Undergraduate Research also deserves a special thanks, for its continued support of both this work and the work of countless other students. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

FORUM Holocaust Scholarship and Politics in the Public Sphere: Reexamining the Causes, Consequences, and Controversy of the Historikerstreit and the Goldhagen Debate

Central European History 50 (2017), 375–403. © Central European History Society of the American Historical Association, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0008938917000826 FORUM Holocaust Scholarship and Politics in the Public Sphere: Reexamining the Causes, Consequences, and Controversy of the Historikerstreit and the Goldhagen Debate A Forum with Gerrit Dworok, Richard J. Evans, Mary Fulbrook, Wendy Lower, A. Dirk Moses, Jeffrey K. Olick, and Timothy D. Snyder Annotated and with an Introduction by Andrew I. Port AST year marked the thirtieth anniversary of the so-called Historikerstreit (historians’ quarrel), as well as the twentieth anniversary of the lively debate sparked by the pub- Llication in 1996 of Daniel J. Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. To mark the occasion, Central European History (CEH) has invited a group of seven specialists from Australia, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States to comment on the nature, stakes, and legacies of the two controversies, which attracted a great deal of both scholarly and popular attention at the time. To set the stage, the following introduction provides a brief overview of the two debates, followed by some personal reflections. But first a few words about the participants in the forum, who are, in alphabetical order: Gerrit Dworok, a young German scholar who has recently published a book-length study titled “Historikerstreit” und Nationswerdung: Ursprünge und Deutung eines bundesrepublika- nischen Konflikts (2015); Richard J. Evans, a foremost scholar -

Wendy Lower, Ph.D

Wendy Lower, Ph.D. Acting Director, Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2016- ) Director, Mgrublian Center for Human Rights John K. Roth Professor of History George R. Roberts Fellow Claremont McKenna College 850 Columbia Ave Claremont, CA 91711 [email protected] (909) 607 4688 Research Fields • Holocaust Studies • Comparative Genocide Studies • Human Rights • Modern Germany, Modern Ukraine • Women’s History Brief Biography • 2016-2018, Acting Director, Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. USA • 2014- 2017, Director, Mgrublian Center for Human Rights, Claremont McKenna College • 2012-present, Professor of History, Claremont McKenna College • 2011-2012, Associate Professor, Affiliated Faculty, Department of History, Strassler Family Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Clark University, Worcester, Mass, USA • 2010-2012 Project Director (Germany), German Witnesses to War and its Aftermath, Oral History Department, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. USA • 2010-2012, Visiting Professor, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy • 2007-2012 Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin, LMU • 2004-2009 Assistant Professor (tenure track), Department of History, Towson University USA (on leave, research fellowship 2007-2009) • 2000-2004, Director, Visiting Scholars Program, Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. • 1999-2000 Assistant Professor, Adjunct Faculty, Center for German and Contemporary European Studies, Georgetown University, USA 1 • 1999-2000 Assistant Professor, Adjunct Faculty, Department of History, American University, USA • 1999 Ph.D., European History, American University, Washington D.C. • 1996-1998 Project Coordinator, Oral History Collection of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), Center for the Study of Intelligence, and Georgetown University • 1994 Harvard University, Ukrainian Research Institute, Ukrainian Studies Program • 1993 M.A. -

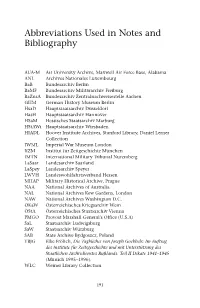

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Introduction Norman J.W

Introduction Norman J.W. Goda E The examination of legal proceedings related to Nazi Germany’s war and the Holocaust has expanded signifi cantly in the past two decades. It was not always so. Though the Trial of the Major War Criminals at Nuremberg in 1945–1946 generated signifi cant scholarly literature, most of it, at least in the trial’s immediate aftermath, concerned legal scholars’ judgments of the trial’s effi cacy from a strictly legalistic perspective. Was the four-power trial based on ex post facto law and thus problematic for that reason, or did it provide the best possible due process to the defendants under the circumstances?1 Cold War political wrangl ing over the subsequent Allied trials in the western German occupation zones as well as the sentences that they pronounced generated a discourse that was far more critical of the tri- als than laudatory.2 Historians, meanwhile, used the records assembled at Nuremberg as an entrée into other captured German records as they wrote initial studies of the Third Reich, these focusing mainly on foreign policy and wartime strategy, though also to some degree on the Final Solution to the Jewish Question.3 But they did not historicize the trial, nor any of subsequent trials, as such. Studies that analyzed the postwar proceedings in and of themselves from a historical perspective developed only three de- cades after Nuremberg, and they focused mainly on the origins of the initial, groundbreaking trial.4 Matters changed in the 1990s for a number of reasons. The fi rst was late- and post-Cold War interest among historians of Germany, and of other nations too, in Vergangenheitsbewältigung—the political, social, and intellectual attempt to confront, or to sidestep, the criminal wartime past. -

Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe Symposium Presentations W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe Symposium Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2004 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2004 Copyright © 2004 by Peter Hayes, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Michael Thad Allen, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Paul Jaskot, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Wolf Gruner, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Christopher R. Browning, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by William Rosenzweig, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Andrej Angrick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Sarah B. Farmer, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Rolf Keller, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................i -

German Defeat/Red Victory: Change and Continuity in Western and Russian Accounts of June-December 1941

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2018 German Defeat/Red Victory: Change and Continuity in Western and Russian Accounts of June-December 1941 David Sutton University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Sutton, David, German Defeat/Red Victory: Change and Continuity in Western and Russian Accounts of June-December 1941, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2018. -

The Shoah in Ukraine in the Framework of Holocaust Studies

Ray Brandon, Wendy Lower, eds.. The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010. 392 pp. $25.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-253-22268-8. Reviewed by Stefan Rohdewald Published on H-Judaic (May, 2013) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) The volume originated in a workshop at the and the slaughter at Babi Yar seem to be “singular United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in episodes” or “most extreme examples” of the 1999. As explained in the introduction, the book pogroms of 1941 and the wave of mass shootings aims at contributing to a shift in the scholarly dis‐ (p. 5). The introduction gives a comprehensive course from the Holocaust in the Soviet Union to sketch of the topic, including a nod to Ukrainian the Holocaust in Ukraine, following the example rescue efforts, reflected in the recognition of 2,185 of research on the Shoah in Poland, Romania, and Righteous among the Nations from Ukraine by Hungary. The introduction thus discusses the Jews Yad Vashem by January 1, 2007. of Ukraine without forgetting to stress that they Dieter Pohl begins the series of contributions did not constitute a homogeneous community. by giving a survey of the Holocaust under German Jews are included in a Ukrainian framework, military and then civil administration as well as which should hinder the characterization of Jews the involvement of Ukrainian police, concentrat‐ as “external” victims, which is quite common in ing on the upper strata of the actors. He shows the Ukrainian context, as in most national con‐ how the mass killings in the framework of Ger‐ texts. -

FORUM Holocaust Scholarship and Politics in the Public Sphere: Reexamining the Causes, Consequences, and Controversy of the Historikerstreit and the Goldhagen Debate

Central European History 50 (2017), 375–403. © Central European History Society of the American Historical Association, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0008938917000826 FORUM Holocaust Scholarship and Politics in the Public Sphere: Reexamining the Causes, Consequences, and Controversy of the Historikerstreit and the Goldhagen Debate A Forum with Gerrit Dworok, Richard J. Evans, Mary Fulbrook, Wendy Lower, A. Dirk Moses, Jeffrey K. Olick, and Timothy D. Snyder Annotated and with an Introduction by Andrew I. Port AST year marked the thirtieth anniversary of the so-called Historikerstreit (historians’ quarrel), as well as the twentieth anniversary of the lively debate sparked by the pub- Llication in 1996 of Daniel J. Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. To mark the occasion, Central European History (CEH) has invited a group of seven specialists from Australia, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States to comment on the nature, stakes, and legacies of the two controversies, which attracted a great deal of both scholarly and popular attention at the time. To set the stage, the following introduction provides a brief overview of the two debates, followed by some personal reflections. But first a few words about the participants in the forum, who are, in alphabetical order: Gerrit Dworok, a young German scholar who has recently published a book-length study titled “Historikerstreit” und Nationswerdung: Ursprünge und Deutung eines bundesrepublika- nischen Konflikts (2015); Richard J. Evans, a foremost scholar -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945. -

The Persecution of Homosexual Foreign Men in Nazi

The Foreign Men of §175: The Persecution of Homosexual Foreign Men in Nazi Germany, 1937-1945 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Andrea K. Howard April 2016 © Andrea K. Howard. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Foreign Men of §175: The Persecution of Homosexual Foreign Men in Nazi Germany, 1937-1945 by ANDREA K. HOWARD has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Mirna Zakic Assistant Professor of History Robert A. Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT HOWARD, ANDREA K., M.A., April 2016, History The Foreign Men of §175: The Persecution of Homosexual Foreign Men in Nazi Germany, 1937-1945 Director of Thesis: Mirna Zakic This thesis examines foreign men accused of homosexuality in Nazi Germany. Most scholarship has focused solely on German men accused of homosexuality. Court records from the General State Prosecutor’s Office of the State Court of Berlin records show that foreign homosexual men were given lighter sentences than German men, especially given the context of the law and the punishments foreigners received for other crimes. This discrepancy is likely due to Nazi confusion about homosexuality, the foreign contribution to the German war effort, issues of gender, and because these men were not a part of any German government, military, or all-male organizations. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to sincerely thank those who were most helpful to me as I researched, wrote, and edited this project. -

Multiplying an Army Prussian and German Military Planning and the Concept of Force Multiplication in Three Conflicts by Samuel A

Multiplying an Army Prussian and German Military Planning and the Concept of Force Multiplication in Three Conflicts by Samuel A Locke III Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May 2020 Multiplying an Army Prussian and German Military Planning and the Concept of Force Multiplication in Three Conflicts Samuel A Locke III I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: 4/18/20 Samuel A Locke III, Student Date Approvals: 4/25/20 Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date 4/25/20 Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date 4/25/20 Dr. Kyle Starkey, Committee Member Date 4/25/20 Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT In this thesis the researcher discusses the implementation of force multipliers in the Prussian and German military. Originating with the wars of Frederick the Great and the geographical position of Prussia, force multipliers were key to the defense of the small state. As time continued, this tactic would become a mainstay for the Prussian military in the wars for German unification. Finally, they would be carried through to a grim conclusion with the Second World War and the belief that this tactic would easily make up for Germany’s shortcomings in material and manpower.