Roy Stover Series by Philip Bartlett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KEENE, Carolyn

KEENE, Carolyn Harriet Stratemeyer Adams Geboren: 1892. Overleden: 1982 Zoals veel juniorenmysteries, is de Nancy Drew-serie bedacht en werd (althans in het begin) de plot geschetst door Edward Stratemeyer [> Franklin W. Dixon] van het Stratemeyer Concern. Zijn dochter, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams nam later de uitgeverij over en claimde lange tijd de schrijver te zijn van àlle Nancy Drew-verhalen vanaf 1930 tot 1982. Onderzoek bracht aan het licht dat dit niet het geval was. De Nancy-verhalen werden, evenals andere Stratemeyer-series, geschreven door een aantal voorheen anonieme professionele schrijvers, waarvan de belangrijkste Mildred A. Wirt Benson (zie onder) was tot het moment dat Harriet Adams in 1953 (vanaf nummer 30) inderdaad begon met het schrijven van nieuwe delen en ook de oude delen vanaf 1959 reviseerde. Opmerkelijk en uniek is de zorgvuldigheid waarmee geprobeerd werd alle sporen omtrent de ‘echte’ auteurs uit te wissen. Byzantijnse plotten en samenzweringen werden gesmeed om veranderde copyrights; dossiers van The Library of Congress verdwenen en niet bestaande overheidsambtenaren werden opgevoerd om de namen van de ware schrijvers uit de boeken te laten verdwijnen. (foto: Internet Book List) website: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolyn_Keene en http://www.keeline.com/Ghostwriters.html Nederlandse website: http://ccw.110mb.com/beeldverhalen/publicaties/N/nancydrew/index.htm Mildred Augustine Wirt Benson Geboren: Ladora, Iowa, USA, 10 juli 1905. Overleden: Toledo, Ohio, 28 mei 2002 Mildred Benson schreef de eerste 25 Nancy Drew-titels en nr 30 (uitgezonderd de nrs 8, 9 en 10) en schreef daarnaast nog vele andere juniorentitels, voornamelijk avonturen voor meisjes: Ruth Fielding (o.ps. -

Accelerated Reader Book List 08-09

Accelerated Reader Book List 08-09 Test Number Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3.0 0.5 107287EN 15 Minutes Steve Young 4.0 4.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Gr Verne/Vogel 5.2 3.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4.0 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.2 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4.0 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.7 2.0 71428EN 95 Pounds of Hope Gavalda/Rosner 4.3 2.0 81642EN Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6.0 11151EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 76357EN The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6.0 9751EN Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't R Debbie Dadey 4.0 1.0 117747EN Abracadabra! Magic with Mouse an Wong Herbert Yee 2.6 0.5 815EN Abraham Lincoln Augusta Stevenson 3.5 3.0 17651EN The Absent Author Ron Roy 3.4 1.0 10151EN Acorn to Oak Tree Oliver S. Owen 2.9 0.5 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10.0 7201EN Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg 1.7 0.5 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory 5.5 4.0 76892EN Actual Size Steve Jenkins 2.8 0.5 86533EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Michael Winerip 5.4 9.0 118142EN Adam Canfield, -

A Nancy for All Seasons

Tanja Blaschitz A Nancy For All Seasons DIPLOMARBEIT zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Magistra der Philosophie Studium: Lehramt Unterrichtsfach Englisch/ Unterrichtsfach Italienisch Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften Begutachter: Ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Heinz Tschachler Institut: Anglistik und Amerikanistik April 2010 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende wissenschaftliche Arbeit selbststän- dig angefertigt und die mit ihr unmittelbar verbundenen Tätigkeiten selbst erbracht habe. Ich erkläre weiters, dass ich keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel be- nutzt habe. Alle aus gedruckten, ungedruckten oder dem Internet im Wortlaut oder im wesentlichen Inhalt übernommenen Formulierungen und Konzepte sind gemäß den Re- geln für wissenschaftliche Arbeiten zitiert und durch Fußnoten bzw. durch andere genaue Quellenangaben gekennzeichnet. Die während des Arbeitsvorganges gewährte Unterstützung einschließlich signifikanter Betreuungshinweise ist vollständig angegeben. Die wissenschaftliche Arbeit ist noch keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt wor- den. Diese Arbeit wurde in gedruckter und elektronischer Form abgegeben. Ich bestätige, dass der Inhalt der digitalen Version vollständig mit dem der gedruckten Ver- sion übereinstimmt. Ich bin mir bewusst, dass eine falsche Erklärung rechtliche Folgen haben wird. Tanja Blaschitz Völkermarkt, 30. April 2010 iii Acknowledgement I can no other answer make, but, thanks, and thanks. by William Shakespeare I would like to use this page to thank the following persons who made the com- pletion of my diploma thesis possible: At the very beginning I would like to thank Professor Heinz Tschachler for his kind support and stimulating advice in the supervision of my diploma thesis. I would also like to thank my dearest friends who have helped me with words and deeds throughout my education. -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

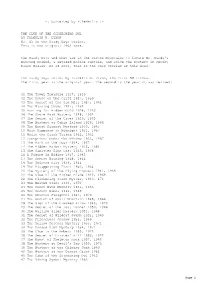

THE YELLOW FEATHER MYSTERY by FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 33 in the Hardy Boys Series

THE YELLOW FEATHER MYSTERY By FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 33 in the Hardy Boys series. This is the 1953 original text. In the 1953 original, the Hardy Boys go to the Woodson Academy to solve the mystery of a missing will. The 1971 revision is slightly altered. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 The Secret of the Lost Tunnel 1950, 1968 30 The Wailing Siren Mystery 1951, 1968 31 The Secret of Wildcat -

THE SECRET PANEL by FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 25 in the Hardy Boys Series

THE SECRET PANEL By FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 25 in the Hardy Boys series. This is the original 1946 text. In the 1946 original, the Hardy Boys solve a kidnapping mystery at the weird Mead House, which lacks both door knobs and hinges. The 1969 revision is altered. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 The Secret of the Lost Tunnel 1950, 1968 30 The Wailing Siren Mystery 1951, 1968 31 The Secret of -

The Clue of the Screeching Owl by Franklin W

-: Converted by FileMerlin :- THE CLUE OF THE SCREECHING OWL BY FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 41 in the Hardy Boys series, This is the original 1962 text. The Hardy Boys and Chet are in the Pocono Mountains to locate Mr. Hardy's missing friend, a retired police captain, and solve the mystery of spooky Black Hollow. As of 2002, this is the only version of this book. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 -

Accelerated Reader Tests by Title

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 04/26/10, 09:04 AM Kuna Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 8451 100 Questions and Answers about AIDSMichael Ford UG 7.5 6.0 English Nonfiction 17351 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BaseballBob Italia MG 5.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17352 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BasketballBob Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17353 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro FootballBob Italia MG 6.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 17354 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro GolfBob Italia MG 5.6 1.0 English Nonfiction 17355 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro HockeyBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 17356 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro TennisBob Italia MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in SummerBob Olympics Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter OlympicsBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 61265 12 Again Sue Corbett MG 4.9 8.0 English Fiction 14796 The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman MG 4.4 4.0 English Fiction 11101 A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald MG 7.7 1.0 English Nonfiction 907 17 Minutes to Live Richard A. Boning 3.5 0.5 English Fiction 44803 1776: Son of Liberty Elizabeth Massie UG 6.1 9.0 English Fiction 8251 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair MG 5.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 44804 1863: A House Divided Elizabeth Massie UG 5.9 9.0 English Fiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 9801 1980 U.S. -

The Disappearing Floor Free Ebook

FREETHE DISAPPEARING FLOOR EBOOK Franklin W. Dixon | 180 pages | 14 Oct 2000 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448089195 | English | New York, NY, United States The Disappearing Floor (revised text) HARDY BOYS # - THE DISAPPEARING FLOOR FRANKLIN W DIXON CHAPTER I Weird Screams "HEY, Frank! Isn't that the black car Dad told us to watch for?" exclaimed Joe Hardy. A sleek foreign sports car with a dented trunk had just whizzed past the Hardy boys' convertible as they drove through the downtown section of Bayport. "Sure looks like it!". The Disappearing Floor by Dixon, Franklin W. and a great selection of related books, art and collectibles available now at Disappearing Floor, First Edition - AbeBooks Passion for books. While looking for a missing scientist, Frank and Joe get more than they bargained for with a UFO that runs them off the road and an old house with growing rooms and disappearing floors. The boys also discover that someone else is looking for the scientist - a couple of Russian agents. The Disappearing Floor is a good, fun episode. The Disappearing Floor A disappearing floor, a huge, savage-looking, hound, a galloping ghost, and a college professor’s startling invention are just a few of the strange elements that complicate the boys’ efforts to solve both mysteries. Also in The Hardy Boys. What I found interesting was how the writers from the Hardy Boys TV show got ideas for their "The Disappearing Floor" episode, from this book, even though the stories are totally different. For example, the fake snarling electric dog in the book, the fake wolves in the TV show. -

The Ghost of Nancy Drew

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online The Ghost of Nancy Drew GEOFFREY S. LAPIN "It would be a shame if all that money went to the Tophams! They will fly higher than ever!" Thus begins the first book in a series of titles that has whetted the literary appetites of young readers for well over fifty years. The Secret of the Old Clock by Carolyn Keene was to set the tone of juvenile adventure stories that is still leading young folks into the joys of reading the standard classics of literature. Carolyn Keene has been writing the series books chronicling the adventures of Nancy Drew and the Dana Girls since 1929. With over 175 titles published, the author is still going strong, presently producing over fifteen new books each year. Her titles have been translated into at least twelve different lan guages, and sales records state that the volumes sold number in the hundreds of millions. More than the mystery of the endurance of such unlikely literature is the question of who Carolyn Keene is and how one person could possibly be the author of such a record number of "best-sellers." Numerous literary histories offer conflicting information concerning the life of Ms Keene. The one common fact is that there exists no actual person by that name. Carolyn Keene is a pseudonym for the author of the series books. Carolyn Keene was Edward Stratemeyer. Another source says that she was Harriet Adams. Yet others say that she was Edna Squire, Walter Karig, James Duncan Lawrence, Nancy Axelrad, Margaret Scherf, Grace Grote, and a plethora of others. -

Danger Overseas Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DANGER OVERSEAS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carolyn Keene,Franklin W. Dixon | 224 pages | 06 May 2008 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781416957775 | English | New York, NY, United States Danger Overseas PDF Book Sep 01, Eleni rated it it was amazing. Manufacturers, suppliers and others provide what you see here, and we have not verified it. We're committed to providing low prices every day, on everything. Furthermore, if you're working and living in a country with a weak currency, your dollars are going to go a lot further. Photo Credits. They must also have experience arranging moves for dangerous goods. Get A Copy. Refresh and try again. Three of the best teen detectives of all time. Pickup not available. See how that works? The Nancy Drew books were condensed, racial stereotypes were removed, and the language was updated. Lockheed Martin 4. Here at Walmart. Additional details. Detriments "Dangerous" is the operative word. Jul 12, Megan rated it it was ok. Dec 13, Rachel rated it it was amazing Shelves: favorite. Skip to main content Indeed logo. Be the Face of the Milspace Office and Organization, welcoming guests, new employees and customers. View 1 comment. Manage all aspects of the dangerous goods shipping program by ensuring items are classified properly in compliance with domestic and international dangerous…. Want to Read saving…. Jun 29, Lauren rated it liked it. Minimum 7 years of experience negotiating domestic and international terms and…. The team is responsible for US and international financial and tax reporting for numerous Lockheed Martin entities, as well as providing support for expat…. I know, George, but isn't it strange to find an American girl in the middle of Rome with no memory of how she got here? It's cliff hanging! Marissa rated it really liked it Feb 28, Danger Overseas Writer SBM Offshore 4. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Mystery at The

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Mystery at the Crossroads by Carolyn Keene The Elusive Heiress (Nancy Drew mystery series) Once again, Nancy Drew is called upon to solve a baffling case. Her search for a missing heiress takes her to a Wild West rodeo and involves her in a terrifying ambush. "About this title" may belong to another edition of this title. Shipping: FREE Within United Kingdom. Other Popular Editions of the Same Title. Featured Edition. ISBN 10: 0671624784 ISBN 13: 9780671624781 Publisher: Simon & Schuster, 1988 Softcover. Wander. 1982 Softcover. Pocket. 1988 Softcover. Customers who bought this item also bought. Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace. 1. The Elusive Heiress (Nancy Drew mystery series) Book Description Armada 26/01/1984, 1984. Condition: Very Good. Shipped within 24 hours from our UK warehouse. Clean, undamaged book with no damage to pages and minimal wear to the cover. Spine still tight, in very good condition. Remember if you are not happy, you are covered by our 100% money back guarantee. Seller Inventory # 6545-9780006921691. 2. The Elusive Heiress (Nancy Drew mystery series) Book Description -, 1984. Paperback. Condition: Very Good. The Elusive Heiress (Nancy Drew mystery series) This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping.