HABS Guide to Field Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving Historic Ornamental Plaster David Flaharty

PRESERVATION BRIEFS Preserving Historic Ornamental Plaster David Flaharty U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Cultural Resources Heritage Preservation Services From the time America struggled for a new identity as the 1930s. During this two hundred year period, as the a constitutional republic-and well into the 20th Georgian and Federal styles yielded to the revivals century-its architecture and its decorative detailing Greek, Rococo, Gothic, Renaissance, and Spanish remained firmly rooted in the European classicism of decorative plaster reflected each style, resulting in the Palladio, Wren, and Mansart. wide variety of ornamentation that survives. The tradi tional methods of producing and installing interior Together with skilled masons and carpenters, orna decorative plaster were brought from Europe to this mental plasterers saw their inherited trade flourish country intact and its practice remains virtually un from the mid-18th century until the Depression years of changed to this day. Fig. 1. Ornamental plaster studios employed the following personnel: Draftsmen to interpret architectural details in shop drawings; sculptors who modelled in clay; model makers who assembled sculpted, plain-run and pre-cast elements into an ornamental unit; moldmakers who made rigid or flexible negative tooling; casters who made production units; finishers (often the caster's wives) who cleaned the casts; and laborers who assisted skilled personnel in operating efficiently. This studio was in Philadelphia, c. 1915. Photo: Courtesy, M. Earle Felber. Styles of Decorative Plaster in America, 18th-20th Centuries d e (a) Kenmore, Fredericksburg, Virginia. c. 1752. Georgian in style with orna mental ceilings based on Batty Langley's 1739 English style book, the plaster work was executed by a Frenchman in the mid-1770s. -

CURRIES Price Book Issued May 2018

CURRIES Price Book Issued May 2018 Revised October 2019 i Index General Information May, 2018 DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) Policies 1 Policies Continued 2 General Information 3 Doors 3 Frames 3 Component Parts for Frames 3 Door and Frame Order Conditions 3 Trademark Use Policy 4 Weights — Doors 5, 6 607S Series 5 707S Series 5 727S Series 5 737S Series 5 747S Series 6 757S Series 6 847S Series 6 857S Series 6 Factory Glazed Doors 7 Weights — KD Frames 8, 9 M Profile 8 C Profile 9 C-CM Profile 9 Weights — Frame Components 10, 11 M Profile 10 C Profile 11 C-CM Profile 11 Weights — CCW 12 Swift-Pac Doors and Frames 13 Notes General Information May, 2018 1 Policies General Information May, 2018 YOUR CURRIES DISTRIBUTOR MANUAL You will find this manual an important source of information for CURRIES products. As new information is developed, or as changes occur, the new material will be mailed directly to you. If you will insert the new pages as received, your CURRIES Manual will always be current . POLICIES TERMS WARRANTY CURRIES reserves the right to refuse purchase orders and is not bound We warrant our products against defects in workmanship to honor them unless they have been accepted at the Mason City, and materials for a period of one year as follows: Iowa, home office. CURRIES reserves the right to sell or not to sell (a) There are no warranties, express or implied, which extend to a firm for any reason which in their sole discretion seems appropriate. beyond those described herein, and there is no implied Terms are 2% ten days and net 30 days from date of invoice. -

Moore & Wright 2016/17- Complete Catalogue

MW-2016E MW-2016E MOORE & WRIGHT Moore & Wright - Europe and North Africa Moore & Wright - Rest of the World Bowers Group Bowers Eclipse Equipment (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Unit 3, Albany Court, 8th Building, No. 178 Chengjian Rd Albany Park, Camberley, Minhang District, Shanghai 201108 Surrey GU16 7QR, UK P.R.China Telephone: +44 (0)1276 469 866 Telephone: +86 21 6434 8600 Fax: +44 (0)1276 401 498 Fax: +86 21 6434 6488 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.moore-and-wright.com Website : www.moore-and-wright.com PRODUCT CATALOGUE 16/17 Partners in Precision PRODUCT CATALOGUE 16/17 INNOVATIVE NEW PRODUCTS IN EVERY SECTION OF THIS ALL-INCLUSIVE, EASY TO USE REFERENCE MWEX2016-17_FC-BC.indd 1 19/11/2015 11:58 MOORE & WRIGHT A Brief History... Founded in 1906 by innovative young engineer, Frank Moore, Moore & Wright has been designing, manufacturing and supplying precision measuring equipment to global industry for over 100 years. With roots fixed firmly in Sheffield, England, the company began by manufacturing a range of calipers, screwdrivers, punches and other engineer’s tools. Following investment from Mrs Wright, a shrewd Sheffield businesswoman, Frank was able to expand the business and further develop his innovative designs. By the mid-nineteen twenties, thanks to the company’s enviable reputation, Moore & Wright was approached by the UK Government to consider manufacturing a range of quality micrometers. It was in this field that Moore & Wright’s status as UK agent for the Swiss Avia range of products and subsequent acquisition of the Avia brand and manufacturing rights, proved invaluable. -

Pultex Pultrusion Design Manual of Standard and Custom Fiber Reinforced Polymer Structural Profiles Imperial Version Volume 5 – Revision 3

The Pultex® Pultrusion Design Manual of Standard and Custom Fiber Reinforced Polymer Structural Profiles Imperial Version Volume 5 – Revision 3 Featuring PultexStandard Structural Profiles Pultex SuperStructural Profiles Nuclear test tower constructed using Pultex® Standard Structural Profiles Creative Pultrusions, Inc. reserves the right to edit and modify literature, please consult the web site for the most current version of this document. “The first Pultex® Design Manual was published in 1973. The New and Improved Pultex® Pultrusion Design Manual of Standard and Custom Fiber Reinforced Polymer Structural Profiles, 2004 Edition, Volume 5 – Revision 3 is a tool for engineers to specify Pultex® pultruded standard structural profiles. Creative Pultrusions, Inc. consistently improves its information to function as a solid reference for engineers.” “No portion of this Design Manual may be reproduced in any form without the prior written consent of Creative Pultrusions, Inc.” Volume 5 - Revision 3 Copyright© 2016 by Creative Pultrusions, Inc. All Rights Reserved Creative Pultrusions®, Flowgrip®, Pultex®, Supergrate®, SUPERPILE®, Superplank®, SuperLoc® and Superdeck® are registered trademarks of Creative Pultrusions, Inc. Superstud!™, Superstud!™/Nuts!, SUPURTUF™, Tuf-dek™, SuperWale™, SuperCap™ and SuperRod™are trademarks of Creative Pultrusions, Inc. i The New and Improved Pultex® Pultrusion Global Design Manual Contents The New and Improved Pultex® Pultrusion Design Manual of Standard and Custom Fiber Reinforced Polymer Structural Profiles, -

Coop Station Observations

Department of Commerce $ National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration $ National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE MANUAL 10-1315 APRIL 18, 2007 Operations and Services Surface Observing Program (Land), NDSPD 10-13 Cooperative Station Observations NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: OS7 (J.Newkirk) Certified by: OS7 (D. McCarthy) Type of Issuance: Emergency SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This Directive supersedes National Weather Service Manual, Cooperative Station Observations, dated September 21, 2006. Re-wrote section 4.1 page A-6, added M for missing data section 4 page D-15 and section 10 page E-6. Moved winterizing Universal Gage out of the F&P Section to the Universal Section. Minor word changes. Signed April 4, 2007 Dennis McCarthy Date Director, Office of Climate Water and Weather Services NWSM 10-1315 APRIL 18, 2007 Cooperative Station Observations Table of Contents: Page 1 Purpose.......................................................................................................................................3 2. Definition of a Cooperative Station...........................................................................................3 3. Reporting Elements....................................................................................................................3 3.1 Precipitation......................................................................................................................3 3.2 Air Temperature................................................................................................................3 -

1.800.KLEENBLAST Table of Contents

Product Catalog INSIDE: You’ll Find Our In-Stock Abrasives, Surface Preparation, and Coating Equipment If You Can’t Find It.. CALL US - WE CAN 1.800.KLEENBLAST WWW.KLEENBLAST.COM Table of Contents Company Profile A: BLAST CABINETS & SPECIALIZED EQUIPMENT KBV Model 86 Blast and Vacuum System …………….. ...............................................1 KBV Model 86 Blast and Vacuum Parts …………….. ...................................................2 KBV Model 36 Best Value Professional Suction Blast Cabinet .................................3 KBV Model 36 Best Value Professional Parts ..............................................................4 Clemco / Zero Production Air Blast Cabinet Systems ...............................................5,6 Empire Blast Production Air Blast Cabinets ...............................................................7,8 Automated Cabinets .............................................................................................................9 Blast Cabinet Replacement Parts ...........................................................................10,11,12 Blast Nozzles Pressure and suction……………………………………… .......13,14 Gloves ....................................................................................................................................15 Specialized Low cost Suction Blasters ……………………………………… ..16,17 B: ABRASIVES ........................................................................................................................... 18-24 C: CONTRACTOR AND INDUSTRIAL FACILITY EQUIPMENT -

Windows and Exterior Doors Wood | Wood-Alu

WINDOWS AND EXTERIOR DOORS WOOD | WOOD-ALU PRODUCT OVERVIEW NATURALLY DIFFERENT... INTERNATIONAL 02 03 DÖPFNER WOOD ALUMINIUM PROFESSIONALS ALL NATURE FOR WINDOWS AND EXTERIOR DOORS OUTSIDE YOUR WINDOW. We are the specialist for wood windows and wood aluminium windows as well as exterior AND INSIDE TOO! door systems made from regional wood and recycled aluminium. All products are made from regional wood and recycled aluminium which results in less pressure on the environment and higher quality for you. Natural resources like wood built the foundation for our company’s philosophy which is based on sustainability and respect for the environment. Döpfner will provide you with the best possi- ble solution for your windows and exterior doors using wood directly from our region. Among our vast variety of products you can find many different system solutions and profile types. On the following pages you have all the information necessary to find the answers to almost any structural requirements. INHALT NATURALLY DIFFERENT Ecological solutions by Döpfner 04 TECHNICAL OVERVIEW Added value – Typical Döpfner Quality 10 WOOD ALUMINIUM WINDOW SYSTEMS Systems overview 33 WOOD WINDOW SYSTEMS Systems overview 49 PROTECT WINDOW SYSTEMS Systems overview 50 Living with nature – inside and outside… DÖPFNER EXTERIOR DOORS Being conscious of our environment now is what Overview | Extract from our full range 58 ensures us a world worth living in the future. DÖPFNER INDIVIDUALITY We can built (almost) every exterior door 68 HARDWARE | LOCKING SYSTEM Construction and examples 72 04 05 WHAT MAKES DÖPFNER NATURALLY DIFFERENT? NATURALLY DIFFERENT – CUSTOMERS WHO ARE DIFFERENT THEMSELVES! THE DÖPFNER Our customers demand high-end products that are based on ECOLOGICAL standards. -

Product Catalog 2019

OPTOELECTRONIC INSTRUMENTS AND SYSTEMS FOR GEOMETRIC QUANTITIES MEASUREMENT PRODUCT CATALOG 2019 DISPLACEMENT AND POSITION GAP MEASUREMENT MEASUREMENT THICKNESS AND WIDTH PROFILE MEASUREMENT MEASUREMENT OUTER DIAMETER AND PROFILE LEVEL MEASUREMENT MEASUREMENT INNER DIAMETER AND PROFILE 2D MEASUREMENT MEASUREMENT VIBRATION AND RUN-OUT 3D MEASUREMENT MEASUREMENT STRAIGHTNESS AND FLATNESS MACHINE VISION SYSTEMS MEASUREMENT ISO 9001-2015 RIFTEK GROUP OF COMPANIES The parent company, Scientific and Production Company «RIFTEK» was founded in 1993. The enterprise specializes in development and fabrication of optoelectronic instruments for measuring of geometrical quantities. The group also includes: Enterprise «RIFTEK TECHNO» – manufacturing of mechanical parts and components for the parent company, contract manufacturing; Enterprise «RIFTEK-SMT» – automated assembling of printed circuit boards (PCB), contract manufacturing; Enterprise «Riftek Russia» – assembly unit in Russia. The basic product line includes: ଶ laser triangulation position sensors, ଶ 2D and 3D laser scanners, ଶ absolute linear encoders, ଶ optical micrometers, ଶ hardware and software system for welding robots, ଶ specialized systems for measuring dimensions, displacements and distances, thickness, diameter, etc., ଶ measurement instruments for railway transport, ଶ video processing FPGA IP-cores and hardware, ଶ machine vision systems. RIFTEK products are delivered in more than 60 countries. Company representative offices operate in 45 countries. RIFTEK company is certified according -

Moving the Mountain

MovingMoving thethe Mountain:Mountain: GuideGuide toto MovingMoving CollectionsCollections COPYRIGHT Science Museum of Minnesota 2001 Everything you’ve always wanted to know about getting all that stuff from here to there... AN ANNOTATED TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR MOVING THE MOUNTAIN Part I: History of the SMM Move Project This section, written by the major planners, describes the goals of the project and early planning considerations. Part II: Moving the Collections Section II presents an overview and analysis of SMM procedures written for the most part by the staff who actually carried them out. Planning Writing Grants Estimating Storage Requirements Scheduling and Staffing Estimating Costs Organizing Staff Collections Department Conservation Department Curatorial Departments COPYRIGHT Management Packing Finding Storage Space Buying SuppliesScience and Services Museum of Minnesota Using Volunteers Managing Projects Developing Packing Protocols Standalone Exhibits 2001 Hmong House NAGPRA Tracking Objects Offices and Laboratories Moving Staging Traffic New Building Storage and Unpacking Part III: Details This section includes an exhaustive description of our conservation technologies, written by the Conservator; the unique requirements of moving articulated fossils, from the Director of the Paleontology Program; and a close look at how the ethnol- ogy collections were put away in the new facility through the eyes of the Collec- tions Technicians who did it. Packing Methodologies Introduction Special Needs Criteria for Packing Definitions Mounting and Packing Methods The Special Case of Dinosaurs Unpacking Ethnology at the New Museum Appendices: Sample Forms Data Dictionary Protocols Status Reports Workplan for Biology Moving the Mountain: The Science Museum of Minnesota Guide to Moving Collections COPYRIGHT Science Museum of Minnesota 2001 Collections Management and Conservation Departments The Science Museum of Minnesota St. -

133441 Wood Portable Buildings.Pdf

~758~ NYSOPRHP – TACONIC REGION Contract D005805: Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site Construction of Elevator/Restroom Addition, Interior and Exterior Rehabilitation and Site Enhancements SECTION 13 34 41 WOOD PORTABLE BUILDINGS PART 1 GENERAL 1.01 SECTION INCLUDES A. Provide a factory made, wood framed, storage building. B. Building Construction Type: IBC Type V-B Wood Frame suitable for Class S (Strorage Occupancy) and other occupancies as determined by Code Authorities. 1.02 REFERENCE STANDARDS A. Codes that shall be met by manufacturer. 1. All work shall comply with the related provisions of the 2017 Uniform Code of New York State which adopts the 2020 IBC, its reference standards, and all local law regulations. B. ASTM E108 - Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Coverings; 2011. 1.03 ADMINISTRATIVE REQUIREMENTS A. Manufacturer shall furnish a Project Manager to follow the project from order to delivery. B. Sequencing: Contractor shall ensure that utility connections are achieved in an orderly and correct manner for immediate connection of factory made for portable wood framed building upon delivery. 1.04 SUBMITTALS A. Product Data: Wood Portable Building Manufacturer shall provide the following. 1. Color Chips for exterior and interior paint, describing which items get which colors. Submittals shall include the paint manufacturer's description of the different types of paint used. 2. Roofing Manufacturer, profile, gauge, color and fastener system and perimeter trim. 3. Siding Manufacturer, profile, material, thickness, color and fastener system. 4. Trim: Interior and exterior: material, Profile size and thickness, fasteners and finish. 5. Underlayment: For Roof, walls and floorings (as may be applicable). -

Definitions of General Technical Skills1 Definitions of Knowledge2

Appendix Definitions of General Technical Skills1 Equipment Maintenance — Performing routine maintenance on equipment and determining when and what kind of maintenance is needed. Equipment Selection — Determining the kind of tools and equipment needed to do a job. Installation — Installing equipment, machines, wiring, or programs to meet specifications. Operation and Control — Controlling operations of equipment or systems. Operation Monitoring — Watching gauges, dials, or other indicators to make sure a machine is working properly. Operations Analysis — Analyzing needs and product requirements to create a design. Programming — Writing computer programs for various purposes. Quality Control Analysis — Conducting tests and inspections of products, services, or processes to evaluate quality or performance. Repairing — Repairing machines or systems using the needed tools. Technology Design — Generating or adapting equipment and technology to serve user needs. Troubleshooting — Determining causes of operating errors and deciding what to do about it. 2 Definitions of Knowledge Administration and Management — Knowledge of business and management principles involved in strategic planning, resource allocation, human resources modeling, leadership technique, production methods, and coordination of people and resources. Biology — Knowledge of plant and animal organisms, their tissues, cells, functions, interdependencies, and interactions with each other and the environment. Building and Construction — Knowledge of materials, methods, and the tools -

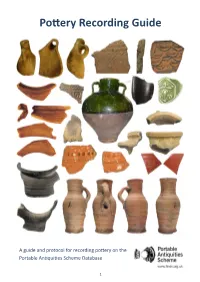

Pottery Recording Guide

Pottery Recording Guide A guide and protocol for recording pottery on the Portable Antiquities Scheme Database 1 Contents Acknowledgements 3 6. List of vessel types 37 6.1 The three basic vessel types 38 1. Introduction 4 6.2 Alphabetical list of vessel types 39-42 1.1 Conventions used in the Guide 4 7. Other ceramic objects 43 2. Pottery for the non-specialist 5 7.1 Lighting equipment 43 2.1 Why record pottery? 5 7.2 Fire covers (curfews) 43 2.2 Dating pottery 5 7.3 Moulds 43 2.3 What are clays, ceramics and pottery? 6 7.4 Crucibles and cupels 44 1. Clays 6 7.5 Briquetage 44 2. Ceramics 6 7.6 Kiln furniture and kiln wasters 45-46 3. Inclusions 7 7.7 Weights - spindle-whorls, loomweights, 4. Pottery 7 other ceramic weights 46-47 2.4 Finding help with your local pottery 7 7.8 Pipeclay objects - smoking pipes, figurines, dolls, hair-curlers 48-49 3. Recording pottery on the PAS database 8 7.9 Ceramic building material (CBM) 50 3.1 The Object Type field and the Brick and tile in the Roman world 50 Classification fields 8 Medieval brick 51 3.2 The Object Description field—the basics 9 Post-medieval brick 51 3.3 The Material fields 9 Roman tile 52 3.4 The Method of Manufacture field 10 Medieval tile 52-53 3.5 The Surface Treatment field 11 Post-medieval tile 53 3.6 The Object Description field in detail 11 Field drains and drain pipes 54 1.