Dubbing and Subtitling in Films the Lecture Contains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bollywood Lens Syllabus

Bollywood's Lens on Indian Society Professor Anita Weiss INTL 448/548, Spring 2018 [email protected] Mondays, 4-7:20 pm 307 PLC; 541 346-3245 Course Syllabus Film has the ability to project powerful images of a society in ways conventional academic mediums cannot. This is particularly true in learning about India, which is home to the largest film industries in the world. This course explores images of Indian society that emerge through the medium of film. Our attention will be focused on the ways in which Indian society and history is depicted in film, critical social issues being explored through film; the depicted reality vs. the historical reality; and the powerful role of the Indian film industry in affecting social orientations and values. Course Objectives: 1. To gain an awareness of the historical background of the subcontinent and of contemporary Indian society; 2. To understand the sociocultural similarities yet significant diversity within this culture area; 3. To learn about the political and economic realities and challenges facing contemporary India and the rapid social changes the country is experiencing; 4. To learn about the Indian film industry, the largest in the world, and specifically Bollywood. Class format Professor Weiss will open each class with a short lecture on the issues which are raised in the film to be screened for that day. We will then view the selected film, followed by a short break, and then extensive in- class discussion. Given the length of most Bollywood films, we will need to fast-forward through much of the song/dance and/or fighting sequences. -

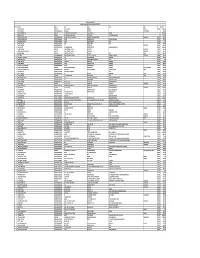

Unpaid Dividend Data As on 31.03.2020

Cummins India Limited Unpaid Dividend Data Interim Dividend 2019-2020 Sr. No. NAM1 FLNO Add1 Add2 Add3 City PIN Amount 1 A GURUSWAMY A005118 J-31 ANANAGAR CHENNAI CHENNAI 600102 8400.000 2 CYRUS JOSEPH . 1202980000081696 2447-(25),2, PATTOM, TRIVANDRUM 196.000 3 GIRIRAJ KUMAR DAGA G010253 C/O SHREE SWASTIK INDUSTRIES DAGA MOHOLLA BIKANER 0 1400.000 4 NEENA MITTAL 0010422 15/265 PANCH PEER STREET NOORI GATE UTTAR PRADESHAGRA 0 14.000 5 PRAVEEN KUMAR SINGH 1202990003575291 THE INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERS BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 336.000 6 PAWAN KUMAR GUPTA IN30021411239166 1/1625 MADARSA ROAD KASHMIRI GATEDELHI 110006 721.000 7 RAJIV MANCHANDA IN30096610156502 A-324-A DERAWAL NAGAR DELHI 110009 7.000 8 VANEET MAKKAR IN30021410957483 E 4/9 MODEL TOWN DELHI 110009 175.000 9 MEENU CHADHA 1203350001859754 F-3 KIRTI NAGAR . NEW DELHI 110015 700.000 10 RAKESH KHER IN30112715640524 E-13 GROUND FLOOR GREEN PARK EXTN NEW DELHINEW DELHI 110016 1400.000 11 RAJNI DHAWAN R027270 C-398, DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 490.000 12 UMESH CHANDRA CHATRATH U004751 C-398, DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 490.000 13 SURESH KUMAR S033265 H.NO.882, GALI NO.57 TRI NAGAR DELHI DELHI 110035 1050.000 14 S N SINGH 1202990001556651 ALPHA TECHNICAL SERVICES PVT LTD A 22 BLOCK B 1 MOHAN CO IND AREA NEW DELHI 110044 98.000 15 SAUDAMINI CHANDRA IN30021410834754 C-12 GULMOHAR PARK NEW DELHI 110049 980.000 16 MADHU RASTOGI IN30236510099372 C-124, SHAKTI NAGAR EXTENSION, DELHI 110052 7.000 17 SHASHI KATYAL IN30159010012885 C- 1 A/106 c JANAK -

Nation, Fantasy, and Mimicry: Elements of Political Resistance in Postcolonial Indian Cinema

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA Aparajita Sengupta University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sengupta, Aparajita, "NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA" (2011). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 129. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aparajita Sengupta The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aparajita Sengupta Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Michel Trask, Professor of English Lexington, Kentucky 2011 Copyright© Aparajita Sengupta 2011 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA In spite of the substantial amount of critical work that has been produced on Indian cinema in the last decade, misconceptions about Indian cinema still abound. Indian cinema is a subject about which conceptions are still muddy, even within prominent academic circles. The majority of the recent critical work on the subject endeavors to correct misconceptions, analyze cinematic norms and lay down the theoretical foundations for Indian cinema. -

Analyzing Imtiaz Ali As an Auteur

Amity Journal of Media & Communication Studies (ISSN 2231 – 1033) Copyright 2017 by ASCO 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Amity University Rajasthan Analyzing Imtiaz Ali as an Auteur Kanika Kachroo Arya Dnyanasadhana College, Mumbai University, India Abstract Imtiaz Ali is a contemporary Bollywood director whose genre is love stories. He has a stream of experimental love stories to his credit, some bench markers are Jab We Met, Rockstar and Tamasha. Not only is his storytelling a well nurtured individualistic style, but the use of techniques of cinema are also experimental. My research paper will analyse this director in the boundaries of Auteur theory. The research will be a qualitative study and methodology used will be in-depth interviews and observation and use of secondary research resources to build up affirmation towards my hypothesis. This director’s style will be compared with other stalwarts of the genre like Raj Kapoor and Yash Chopra. This will carve out his style more specifically. Imtiaz Ali has a unique style aesthetically as well as technically. He understands the psychology of his target audience and that’s what has carved a niche for him in Bollywood - a cult director of romance genre. Key words: Auteur Theory, Direction, Niche, Bollywood. Introduction Imtiaz Ali is one amongst the contemporary directors of Bollywood. His directorial debut was Socha Na Tha released in 2005. Though the movie did not do well but he received a lot of critical acclaim for it. Jab we Met (2007) and Rockstar (2011) brought him into limelight. Jab We Met was a box office success and Rockstar was appreciated in critical circles for superb rendition of a careless musician. -

100 Essential Indian Films, by Rohit K. Dasgupta and Sangeeta Datta

Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media no. 21, 2021, pp. 239–243 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.21 100 Essential Indian Films, by Rohit K. Dasgupta and Sangeeta Datta. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, 283 pp. Darshana Chakrabarty Among the many film industries of South Asia, the Indian film industry is the most prolific, specifically Hindi language film, more commonly known as Bollywood, which produces almost four hundred films annually. Bollywood films dominate the national market. These films have also been exported successfully to parts of the Middle East, Africa, and the Asiatic regions of the former Soviet Union, as well as to Canada, Australia, the UK, and the US. The success of these films abroad is largely down to the presence of Indian communities living in these regions; as the conventional melodramatic plot structures, dance numbers and musicals tend to deter Western audiences. Within India and abroad “the traditional division between India’s popular cinema and its ‘art’ or ‘parallel’ cinema, modelled after India's most prestigious film-director Satyajit Ray, often produced the uncritical assumption that Indian films are either ‘Ray or rubbish’” (Chaudhuri 137). Recently, Indian film criticism has begun focusing on popular Indian cinema, assessing the multi-discursive elements of the cinematic creations. Bollywood “gained prominence within academia due to its growing popularity and unique manner of glorifying Indian familial values” (Sinha 3). From a history and origin of Indian motion pictures to selecting films that best represent the diversity, integrity and heritage of the nation, 100 Essential Indian Films by Rohit K. Dasgupta and Sangeeta Dutta is a concise book on Indian cinema for connoisseurs and for film enthusiasts taking an interest in India’s classic and contemporary cinema. -

Born Kamal Haasan 7 November 1954 (Age 56) Paramakudi, Madras State, India Residence Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Occupation Film

Kamal Haasan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Kamal Haasan Kamal Haasan Born 7 November 1954 (age 56) Paramakudi, Madras State, India Residence Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Occupation Film actor, producer, director,screenwriter, songwriter,playback singer, lyricist Years active 1959–present Vani Ganapathy Spouse (1978-1988) Sarika Haasan (1988-2004) Partner Gouthami Tadimalla (2004-present) Shruti Haasan (born 1986) Children Akshara Haasan (born 1991) Kamal Haasan (Tamil: கமலஹாசன்; born 7 November 1954) is an Indian film actor,screenwriter, and director, considered to be one of the leading method actors of Indian cinema. [1] [2] He is widely acclaimed as an actor and is well known for his versatility in acting. [3] [4] [5] Kamal Haasan has won several Indian film awards, including four National Film Awards and numerous Southern Filmfare Awards, and he is known for having starred in the largest number of films submitted by India in contest for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[6] In addition to acting and directing, he has also featured in films as ascreenwriter, songwriter, playback singer, choreographer and lyricist.[7] His film production company, Rajkamal International, has produced several of his films. In 2009, he became one of very few actors to have completed 50 years in Indian cinema.[8] After several projects as a child artist, Kamal Haasan's breakthrough into lead acting came with his role in the 1975 drama Apoorva Raagangal, in which he played a rebellious youth in love with an older woman. He secured his second Indian National Film Award for his portrayal of a guileless school teacher who tends a child-like amnesiac in 1982's Moondram Pirai. -

Mohanlal Filmography

Mohanlal filmography Mohanlal Viswanathan Nair (born May 21, 1960) is a four-time National Award-winning Indian actor, producer, singer and story writer who mainly works in Malayalam films, a part of Indian cinema. The following is a list of films in which he has played a role. 1970s [edit]1978 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes [1] 1 Thiranottam Sasi Kumar Ashok Kumar Kuttappan Released in one center. 2 Rantu Janmam Nagavally R. S. Kurup [edit]1980s [edit]1980 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Manjil Virinja Pookkal Poornima Jayaram Fazil Narendran Mohanlal portrays the antagonist [edit]1981 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Sanchari Prem Nazir, Jayan Boban Kunchacko Dr. Sekhar Antagonist 2 Thakilu Kottampuram Prem Nazir, Sukumaran Balu Kiriyath (Mohanlal) 3 Dhanya Jayan, Kunchacko Boban Fazil Mohanlal 4 Attimari Sukumaran Sasi Kumar Shan 5 Thenum Vayambum Prem Nazir Ashok Kumar Varma 6 Ahimsa Ratheesh, Mammootty I V Sasi Mohan [edit]1982 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Madrasile Mon Ravikumar Radhakrishnan Mohan Lal 2 Football Radhakrishnan (Guest Role) 3 Jambulingam Prem Nazir Sasikumar (as Mohanlal) 4 Kelkkatha Shabdam Balachandra Menon Balachandra Menon Babu 5 Padayottam Mammootty, Prem Nazir Jijo Kannan 6 Enikkum Oru Divasam Adoor Bhasi Sreekumaran Thambi (as Mohanlal) 7 Pooviriyum Pulari Mammootty, Shankar G.Premkumar (as Mohanlal) 8 Aakrosham Prem Nazir A. B. Raj Mohanachandran 9 Sree Ayyappanum Vavarum Prem Nazir Suresh Mohanlal 10 Enthino Pookkunna Pookkal Mammootty, Ratheesh Gopinath Babu Surendran 11 Sindoora Sandhyakku Mounam Ratheesh, Laxmi I V Sasi Kishor 12 Ente Mohangal Poovaninju Shankar, Menaka Bhadran Vinu 13 Njanonnu Parayatte K. -

![Knowledge Generation Arxiv:2101.08857V1 [Cs.LG] 21 Jan](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6240/knowledge-generation-arxiv-2101-08857v1-cs-lg-21-jan-3266240.webp)

Knowledge Generation Arxiv:2101.08857V1 [Cs.LG] 21 Jan

MSc Artificial Intelligence Master Thesis Knowledge Generation Variational Bayes on Knowledge Graphs by Florian Wolf 12393339 January 25, 2021 48 Credits April 2020 - January 2021 Supervisor: Dr Peter Bloem Thiviyan Thanapalasingam Chiara SpruijtarXiv:2101.08857v1 [cs.LG] 21 Jan 2021 Assessor: Dr Paul Groth Abstract This thesis is a proof of concept for the potential of Variational Auto-Encoder (VAE) on rep- resentation learning of real-world Knowledge Graphs (KG). Inspired by successful approaches to the generation of molecular graphs, we experiment and evaluate the capabilities and limita- tions of our model, the Relational Graph Variational Auto-Encoder (RGVAE), characterized by its permutation invariant loss function. The impact of the modular hyperparameter choices, encoding though graph convolutions, graph matching and latent space prior, are analyzed and the added value is compared. The RGVAE is first evaluated on link prediction, a common experiment indicating its potential use for KG completion. The model is ranked by its ability to predict the correct entity for an incomplete triple. The mean reciprocal rank (MRR) scores on the two datasets FB15K-237 and WN18RR are compared between the RGVAE and the embedding-based model DistMult. To isolate the impact of each module, a variational Dist- Mult and a RGVAE without latent space prior constraint are implemented. We conclude, that neither convolutions nor permutation invariance alter the scoring. The results show that be- tween different settings, the RGVAE with relaxed latent space, scores highest on both datasets, yet does not outperform the DistMult. Graph VAEs on molecular data are able to generate unseen and valid molecules as a re- sults of latent space interpolation. -

IP Eng Jan-Mar 09.Indd

Vol 23, No. 1 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaJANUARY-MARCH 2009 Perspectives Editor Vinod Kumar Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra Consulting Editor Newsline Publications Pvt. Ltd., C-15, Sector 6, Noida-201301 India Perspectives is published every month in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549, E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, by Parbati Sen Vyas, Special Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. The Indian B.R. Chopra Film Industry A FILM MAKER FOR ALL SEASONS UPENDRA SOOD Editorial 2 58 Shyam Benegal We bring to our readers this time a special issue on Indian PROGENITOR NEW WAVE CINEMA Cinema. There could not have been a better theme for me to 62 commence my editorial stint as Indian and India-based cinema Gulzar seem to be the fl avour of the season. THE VERSATILE MAN AND HIS WORLD India was introduced to ‘moving pictures’ soon after their 66 screening by the Lumierre brothers in Paris. -

Indian Scholar

ISSN 2350-109X www.indianscholar.co.in Indian Scholar An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ‘LOVINGLY RIPPED-OFF’ - COPYRIGHT, CENSORSHIP, AND LEGAL CONSTRAINTS IN LITERARY ADAPTATIONS J. Jaya Parveen Asst. Professor (English) CTTE College for Women, Chennai. 11 In A Theory of Adaptations (2006), Linda Hutcheon observes that film adaptations hold the dual responsibility of adapting another work and making it an autonomous creation. The major danger involved in the motivation to adapt for a wider audience is that more responsibility is placed on the adapters to make the ‘substitute’ experience ‘as good as, or better than (even if different from) that of reading original works’ (Wober 10). With regard to the adapter motivation(s), Hutcheon (2006) has a few questions unanswered: What motivates adapters, knowing that their efforts will be compared to competing imagined versions in people’s heads and inevitably be found wanting? Why would they risk censure for monetary opportunism? (86) For legal reasons, film-makers choose works that are no longer copyrighted. They adapt the ‘tried and tested’ works (e.g., Shakespeare, Dickens, and Jane Austen) to avoid legal and financial risks. For economic reasons, they choose popular literary works for adaptation. Ismail Merchant, in an interview, states that he has spent about two years dealing with V. S. Naipaul’s agents, and was not getting anywhere. Finally he has written a letter to him directly and got a positive reply (Williams 2007). Saving Mr. Banks portrays Walt Disney’s tough fight with Mrs. Travers to get the rights for her book Mary Poppins. An adaptation is an original screenplay; it becomes the sole property of the film-maker and thus a source of financial gain (Brady xi). -

Cinema of India - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Cinema of India - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_film Cinema of India From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Indian film) The cinema of India consists of films produced across India, including the cinematic culture of Mumbai along with the cinematic traditions of states such as Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Karnataka, Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Indian films came to be followed throughout South Asia and the Middle East. As cinema as a medium gained popularity in the country as many as 1,000 films in various languages of India were produced annually. Expatriates in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States continued to give rise to international audiences for Hindi-language films. Devi in the 1929 film, Prapancha Pasha (A Throw of Dice), directed by Franz Osten.jpg|thumb|Charu Roy and Seeta Devi in the 1929 film, Prapancha Pash . In the 20th century, Indian cinema, along with the American and Chinese film industries, became a global enterprise. [1] Enhanced technology paved the way for upgradation from established cinematic norms of delivering product, radically altering the manner in which content reached the target audience. [1] Indian cinema found markets in over 90 countries where films from India are screened. [2] The country also participated in international film festivals especially satyajith ray(bengali),Adoor Gopal krishnan,Shaji n karun(malayalam) . [2] Indian filmmakers such as Shekhar Kapur, Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta etc. found success overseas. [3] The Indian government extended film delegations to foreign countries such as the United States of America and Japan while the country's Film Producers Guild sent similar missions through Europe. -

Heaven on Earth

Mongrel Media Presents A David Hamilton Production of A Film by Deepa Mehta Heaven on Earth (Canada, 106 minutes, Punjabi/English, 2008) Hamilton-Mehta Productions In co-production with The National Film Board of Canada Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SHORT SYNOPSIS Chand (Preity Zinta) is a young woman who travels from India to Canada to marry Rocky (Vansh Bhardwaj), a man she has never met. Her dream of a new life morphs into a nightmare as marriage to Rocky and his family becomes a numbing spiral of confusion and pain. Chand finds hope in her friendship with Rosa (Yanna McIntosh), a street-smart woman from Jamaica who works with Chand at a laundry factory. Rosa gives Chand a magical root and promises that it will make Rocky fall deeply in love with her. The experiment ends in a surreal parallel life that mirrors an Indian fable involving a King Cobra. LONG SYNOPSIS Vibrant and irrepressibly alive, Chand (Preity Zinta) is a young bride leaving her home in Ludhiana, India, for the cavernous landscape of Brampton, Ontario, where her husband Rocky (Vansh Bhardwaj) and his very traditional family await her arrival. Everything is new to Chand; everything is unfamiliar including the quiet and shy Rocky who she meets for the first time at the Arrivals level of Pearson Airport.