Indian Scholar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bollywood Lens Syllabus

Bollywood's Lens on Indian Society Professor Anita Weiss INTL 448/548, Spring 2018 [email protected] Mondays, 4-7:20 pm 307 PLC; 541 346-3245 Course Syllabus Film has the ability to project powerful images of a society in ways conventional academic mediums cannot. This is particularly true in learning about India, which is home to the largest film industries in the world. This course explores images of Indian society that emerge through the medium of film. Our attention will be focused on the ways in which Indian society and history is depicted in film, critical social issues being explored through film; the depicted reality vs. the historical reality; and the powerful role of the Indian film industry in affecting social orientations and values. Course Objectives: 1. To gain an awareness of the historical background of the subcontinent and of contemporary Indian society; 2. To understand the sociocultural similarities yet significant diversity within this culture area; 3. To learn about the political and economic realities and challenges facing contemporary India and the rapid social changes the country is experiencing; 4. To learn about the Indian film industry, the largest in the world, and specifically Bollywood. Class format Professor Weiss will open each class with a short lecture on the issues which are raised in the film to be screened for that day. We will then view the selected film, followed by a short break, and then extensive in- class discussion. Given the length of most Bollywood films, we will need to fast-forward through much of the song/dance and/or fighting sequences. -

The Feminine Eye: Lecture 5: WATER: 2006: 117M

1 The Feminine Eye: lecture 5: WATER: 2006: 117m: May 2: Women Directors from India: week #5 Mira Nair / Deepa Mehta Screening: WATER (Deepa Mehta, 2005) class business: last class: next week: 1. format 2. BEACHES OF AGNES 3. Fran Claggett 2 Women Directors from India: Mira Nair: [Ni-ar = liar] b. 1957: India: education: Delhi [Delly] University: India Harvard: US began film career as actor: then: directed docs 1988: debut feature: SALAAM BOMBAY! kids living on streets of Bombay: real homeless kids used won Camera d’Or: Cannes Film Festival: Best 1st Feature clip: SALAAM BOMBAY!: ch 2: 3m Nair’s stories: re marginalized people: films: focus on class / cultural differences 1991: MISSISSIPPI MASALA: interracial love story: set in US South: black man / Indian woman: Denzel Washington / Sarita Choudhury 2001: MONSOON WEDDING: India: preparations for arranged marriage: groom: Indian who’s relocated to US: Texas: comes back to India for wedding won Golden Lion: Venice FF 2004: VANITY FAIR: Thackeray novel: early 19th C England: woman’s story: Becky Sharp: Witherspoon 2006: THE NAMESAKE: story: couple emigrates from India to US 2 kids: born in US: problems of assimilation: old culture / new culture plot: interweaving old & new Nair: latest film: 2009: AMELIA story of strong pioneering female pilot: Swank 3 Deepa Mehta: b. 1950: Amritsar, India: father: film distributor: India: degree in philosophy: U of New Delhi 1973: immigrated to Canada: embarked on professional career in films: scriptwriter for kids’ movies Mehta: known for rich, complex -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

New York AIDS Film Festival

GIRL BEHIND THE CAMERA PRODUCTIONS IS PROUD TO PRESENT THE FILMS OF THE 2007 NEW YORK AIDS FILM FESTIVAL 5th ANNIVERSARY FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ============================================================================== FILMS OF THE 2007 NY AIDS FILM FESTIVAL OPENING NIGHT – NOV 29th UNITED NATIONS HEADQUATERS SATURDAY DEC 1 & 2ND 2007 – WORLD AIDS DAY SCREENINGS PRESENTED BY -NEW YORK UNIVERSITY TICKETS: FREE REFRESHMENTS: FREE ============================================================================== King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center 53 Washington Square South ============================================================================= Contact: [email protected] 212 591 1434 OPENING NIGHT –NOVEMBER 29TH 2007 UNITED NATIONS HEADQUATERS INVITE ONLY!!! National Geographic & Youth AIDS Indias Hidden Plague Starring Ashley Judd ( FEATURE PRESENTATION) Mirabai Films Mira Nair – AIDS Jaago ( Migration) ( SHORT FILM) Awards will be presented to: Christiane Amanpour ( CNN), Mira Nair ( MIRABAI FILMS), Paolo Monaci ( Golden Graal), Kate Roberts ( Youth AIDS) Actor/Activist -Gloria Reuben Celebrity and VIP Presenters including: actor Josh Lucas, Steve Villano (cable positive), Supermodel Greta Cavazzoni and more. SATURDAY DECEMBER 1st 2007 PROGRAM WORLD AIDS DAY 9:30 – 10:45am MTV STAYING ALIVE- 48 FEST KENYA DOC & SHORTS 48 Fest took place on 3rd of July in the robust city of Nairobi in Kenya at the first ever Women’s Summit on Leadership on HIV and AIDS. 30 young people who attended the summit were given the opportunity to produce these short films. How did it all work? Participants had two days to produce their films from scratch. The brief was to look at the many challenges of HIV and AIDS, but with a female slant. However, the films aren’t just targeted atwomen; in fact everyone might learn something. A panel of expert judges, including acclaimed director Bryan Barber gave their opinions on all six films, and chose an overall winner.Considering all films were shot on zero budget, they really are an amazing feat. -

The Reluctant Fundamentalist

Mongrel Media Presents The Reluctant Fundamentalist A film by Mira Nair (128 min., USA, 2012) Language: English and Urdu Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS 2011, Lahore. At a café a Pakistani man named Changez (Riz Ahmed) tells Bobby (Liev Schreiber), an American journalist, about his experiences in the United States. Roll back ten years, and we find a younger Changez fresh from Princeton, seeking his fortune on Wall Street. The American Dream seems well within his grasp, complete with a smart and gorgeous artist girlfriend, Erica (Kate Hudson). But when the Twin Towers are attacked, a cultural divide slowly begins to crack open between Changez and Erica. Changez’s dream soon begins to slip into nightmare: he is transformed from a well-educated, upwardly mobile businessman to a scapegoat and perceived enemy. Taking us through the culturally rich and beguiling worlds of New York, Lahore and Istanbul, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is a story about conflicting ideologies where perception and suspicion have the power to determine life or death. A MULTI-LAYERED VISION “Looks can be deceiving.” Changez Khan “An Indian director making a film about a Pakistani man. That’s not an easy thing to do,” says novelist and co-screenwriter Mohsin Hamid of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, the new film from award-winning filmmaker Mira Nair, based on Hamid’s acclaimed novel of the same name. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Slumdog Millionaire: the Film, the Reception, the Book, the Global

Wright State University CORE Scholar English Language and Literatures Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures 2012 Slumdog Millionaire: The Film, the Reception, the Book, the Global Alpana Sharma Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/english Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Repository Citation Sharma, A. (2012). Slumdog Millionaire: The Film, the Reception, the Book, the Global. Literature/Film Quarterly, 40 (3), 197-215. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/english/230 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Language and Literatures at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literatures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S1mtido5 l11Dlio11~: ~lte FD11:1., -Cite ~ecop"Cio11., -Cite Book., -Cite 61obel1 Danny Boyle's S/11n1dog Millionaire was the runaway commercial hit of 2009 in the United States, nominated for ten Oscars and bagging eight of these, including Best Picture and Best Director. Also included in its trophy bag arc seven British Academy Film awards, all four of the Golden Globe awards for which it was nominated, and five Critics' Choice awards. Viewers and critics alike attribute the film's unexpected popularity at the box office to its universal underdog theme: A kid from the slums of Mumbai makes it to the game show ll"ho lfa11ts to Be a Mil/io11aire and wins not only the money but also the girl. -

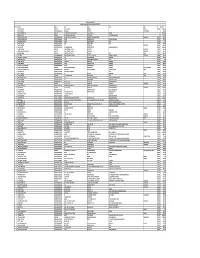

Unpaid Dividend Data As on 31.03.2020

Cummins India Limited Unpaid Dividend Data Interim Dividend 2019-2020 Sr. No. NAM1 FLNO Add1 Add2 Add3 City PIN Amount 1 A GURUSWAMY A005118 J-31 ANANAGAR CHENNAI CHENNAI 600102 8400.000 2 CYRUS JOSEPH . 1202980000081696 2447-(25),2, PATTOM, TRIVANDRUM 196.000 3 GIRIRAJ KUMAR DAGA G010253 C/O SHREE SWASTIK INDUSTRIES DAGA MOHOLLA BIKANER 0 1400.000 4 NEENA MITTAL 0010422 15/265 PANCH PEER STREET NOORI GATE UTTAR PRADESHAGRA 0 14.000 5 PRAVEEN KUMAR SINGH 1202990003575291 THE INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERS BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 336.000 6 PAWAN KUMAR GUPTA IN30021411239166 1/1625 MADARSA ROAD KASHMIRI GATEDELHI 110006 721.000 7 RAJIV MANCHANDA IN30096610156502 A-324-A DERAWAL NAGAR DELHI 110009 7.000 8 VANEET MAKKAR IN30021410957483 E 4/9 MODEL TOWN DELHI 110009 175.000 9 MEENU CHADHA 1203350001859754 F-3 KIRTI NAGAR . NEW DELHI 110015 700.000 10 RAKESH KHER IN30112715640524 E-13 GROUND FLOOR GREEN PARK EXTN NEW DELHINEW DELHI 110016 1400.000 11 RAJNI DHAWAN R027270 C-398, DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 490.000 12 UMESH CHANDRA CHATRATH U004751 C-398, DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 490.000 13 SURESH KUMAR S033265 H.NO.882, GALI NO.57 TRI NAGAR DELHI DELHI 110035 1050.000 14 S N SINGH 1202990001556651 ALPHA TECHNICAL SERVICES PVT LTD A 22 BLOCK B 1 MOHAN CO IND AREA NEW DELHI 110044 98.000 15 SAUDAMINI CHANDRA IN30021410834754 C-12 GULMOHAR PARK NEW DELHI 110049 980.000 16 MADHU RASTOGI IN30236510099372 C-124, SHAKTI NAGAR EXTENSION, DELHI 110052 7.000 17 SHASHI KATYAL IN30159010012885 C- 1 A/106 c JANAK -

Nation, Fantasy, and Mimicry: Elements of Political Resistance in Postcolonial Indian Cinema

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA Aparajita Sengupta University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sengupta, Aparajita, "NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA" (2011). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 129. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aparajita Sengupta The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aparajita Sengupta Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Michel Trask, Professor of English Lexington, Kentucky 2011 Copyright© Aparajita Sengupta 2011 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA In spite of the substantial amount of critical work that has been produced on Indian cinema in the last decade, misconceptions about Indian cinema still abound. Indian cinema is a subject about which conceptions are still muddy, even within prominent academic circles. The majority of the recent critical work on the subject endeavors to correct misconceptions, analyze cinematic norms and lay down the theoretical foundations for Indian cinema. -

July 2014 at BFI Southbank

July 2014 at BFI Southbank Dennis Potter, A Century of Chinese Cinema, Gotta Dance, Gotta Dance! Dennis Hopper with Peter Fonda in person, Richard Lester In Conversation The BFI Southbank’s complete Dennis Potter season, which marks the 20th anniversary of his death and brings together the entire surviving canon of Potter’s work for the first time, continues with this month’s theme The Outsider Inside. July highlights include screenings of Brimstone & Treacle (1982) and complete series screenings of Pennies From Heaven (1978) starring the late Bob Hoskins, and Lipstick on Your Collar (1993). This landmark season will continue in June and July 2015 A Century of Chinese Cinema continues with Swordsmen, Gangsters and Ghosts looking at the evolution of Chinese genre cinema with the popular wuxia (swordplay), martial arts and Hong Kong gangster films which first brought Chinese cinema to international attention. Highlights include Fist of Fury (1972), Police Story (1985), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Infernal Affairs (2002) BFI Southbank will host a month long season dedicated to the actor, director and artist Dennis Hopper; the season will launch on Wednesday 2 July as we welcome Peter Fonda to BFI Southbank to discuss his career, and his friendship and collaborations with Dennis Hopper. The season will include screenings of some of Hopper’s most significant films including Easy Rider (1969), Blue Velvet (1986) and The Last Movie (1971), and coincides with Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album, a photographic exhibition hosted by The Royal Academy of Arts A two month season of dance films, Gotta Dance, Gotta Dance! will begin in July as part of Big Dance 2014. -

Analyzing Imtiaz Ali As an Auteur

Amity Journal of Media & Communication Studies (ISSN 2231 – 1033) Copyright 2017 by ASCO 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Amity University Rajasthan Analyzing Imtiaz Ali as an Auteur Kanika Kachroo Arya Dnyanasadhana College, Mumbai University, India Abstract Imtiaz Ali is a contemporary Bollywood director whose genre is love stories. He has a stream of experimental love stories to his credit, some bench markers are Jab We Met, Rockstar and Tamasha. Not only is his storytelling a well nurtured individualistic style, but the use of techniques of cinema are also experimental. My research paper will analyse this director in the boundaries of Auteur theory. The research will be a qualitative study and methodology used will be in-depth interviews and observation and use of secondary research resources to build up affirmation towards my hypothesis. This director’s style will be compared with other stalwarts of the genre like Raj Kapoor and Yash Chopra. This will carve out his style more specifically. Imtiaz Ali has a unique style aesthetically as well as technically. He understands the psychology of his target audience and that’s what has carved a niche for him in Bollywood - a cult director of romance genre. Key words: Auteur Theory, Direction, Niche, Bollywood. Introduction Imtiaz Ali is one amongst the contemporary directors of Bollywood. His directorial debut was Socha Na Tha released in 2005. Though the movie did not do well but he received a lot of critical acclaim for it. Jab we Met (2007) and Rockstar (2011) brought him into limelight. Jab We Met was a box office success and Rockstar was appreciated in critical circles for superb rendition of a careless musician.