Franz Marc, Hugo Ball, and a Decisive Moment in Dada-Expressionist Theater with a Special Appearance by August Macke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report Provenance Research

Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation Final Report Project management Dr. Thorsten Sadowsky, Director Annick Haldemann, Registrar [email protected] Project handling and report Julia Sophie Syperreck MA, Research Assistant [email protected] 31 August 2018 Kirchner Museum Davos Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 2 Contents 3 I. Work report 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project 5 b. Work performed by the project staff and project schedule 6 c. Methodical approach and manner of publication of the findings 7 d. Object statistics 9 e. List of the historical agents (individuals and institutions) relevant to the project 10 f. Documentation of the findings for third parties 11 II. Summary 12 a. Evaluation of the findings 12 b. Unresolved issues and need for further research 13 III. Appendix: List of works Kirchner Museum Davos I. Work report Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project At the beginning of the project an assessment was made which groups of works within the collection are more likely to be linked to the “liquidation” of private and public collections during the Nazi dictatorship in Germany in the years from 1933 to 1945. It was found that there is only very patchy provenance information for the forty-two artworks donated in 2000 to the Kirchner Museum Davos by “Rosemarie and Konrad Baumgart-Möller in memory of Ferdinand Möller, Berlin.” Since “Möller” is one of the red-flag names in provenance research, the investigation of this part of the collection was given priority. -

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Arthur Sullivan Als Musikdramatiker

Hier die Zusammenfassung eines aktuellen Forschungsbeitrags über Arthur Sullivans Leistungen als Musikdramatiker. Den vollständigen Text in deutscher Sprache finden Sie auf den Seiten 69 – 84 in dem Buch Arthur Sullivan Herausgegeben von Ulrich Tadday Heft 151 der Reihe Musik-Konzepte edition text + kritik, München 2011. Siehe zu dem Aspekt auch die Beiträge in SullivanPerspektiven I Arthur Sullivans Opern, Kantaten, Orchester- und Sakralmusik Herausgegeben von Albert Gier / Meinhard Saremba / Benedict Taylor Oldib-Verlag, Essen 2012. Arthur Sullivan als Musikdramatiker Arthur Sullivan was without doubt the most cosmopolitan British musician of his day. As a music dramatist, Sullivan’s accomplishments are not fundamentally different from other dramatic composers often cited as influences (albeit, influencing different aspects of his works): Handel, Mozart, Rossini, Marschner, Lortzing, Mendelssohn, Auber and Berlioz. The breadth of that list, however, is remarkable. Where Sullivan excelled most of these, though, was his ability to execute the evident conviction that a libretto was not merely a story to be set to music, but rather as dry bones needing to be fleshed out and brought to life through his music and its engagement with the audience. Even at moments when his librettist (especially Gilbert) seems to lose interest in a character, Sullivan invests his work with powerfully sympathetic genius, articulated through calculated juxtaposition of musical style. The essay examines the »lyrical« and »prosaic« modes in his major works as well as the dramatic pacing of Sullivan’s compositions (both for opera and concert platform), e. g. in Ivanhoe, The Golden Legend and The Yeomen of the Guard. 1 SullivanPerspektiven I Arthur Sullivans Opern, Kantaten, Orchester- und Sakralmusik hrsg. -

Claes-Göran Holmberg

fLaMMan claes-Göran holmberg Precursors swedish avant-garde groups were very late in founding their own magazines. in france and Germany, little magazines had been pub- lished continuously from the romantic era onwards. a magazine was an ideal platform for the consolidation of a new movement in its formative phase. it was a collective thrust at the heart of the enemy: the older generation, the academies, the traditionalists. By showing a united front (through programmatic declarations, manifestos, es- says etc.) you assured the public that you were to be reckoned with. almost every new artist group or current has tried to create a mag- azine to define and promote itself. the first swedish little magazine to embrace the symbolist and decadent movements of fin-de-siècle europe was Med pensel och penna (With paintbrush and pen, 1904-1905), published in Uppsala by the society of “Les quatres diables”, a group of young poets and students engaged in aestheticism and Baudelaire adulation. Mem- bers were the poet and student in slavic languages sigurd agrell (1881-1937), the student and later professor of art history harald Brising (1881-1918), the student of philosophy and later professor of psychology John Landquist (1881-1974), and the author sven Lidman (1882-1960); the poet sigfrid siwertz (1882-1970) also joined the group later. the magazine did not leave any great impact on swedish literature but it helped to spread the Jugend style of illu- stration, the contemporary love-hate relationship with the city and the celebration of the intoxicating powers of beauty and deca- dence. -

DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle

MDS 3.2 Unterrichtsprojekte in der Sekundarstufe Freiburg vom 29.06. bis 19.07.2014 Ozana Klein, Gabriele Weiß, Alexandra Effe DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle Der Blaue Reiter ist die Bezeichnung für eine Künstlergruppe Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts in München. Der Name wurde von Wassily Kandinsky und Franz Marc gewählt. Beide waren Maler und Künstler. Kandinsky hatte bereits 1909 ein Bild … … mit dem Titel „Der Blaue Reiter“ geschaffen. Was die Bezeichnung betrifft, sagte Kandinsky: „Den Namen „Der Blaue Reiter“ erfanden wir am Kaffeetisch in der Gartenlaube in Sindelsdorf. Beide liebten wir Blau: Marc – Pferde und ich – Reiter. So kam der Name … … von selbst.“ Zur Farbe Blau schrieb Kandinsky einmal: „Sie weckt in ihm die Sehnsucht nach Reinem und Übersinnlichem. Es ist die Farbe des Himmels“. August Macke und Franz Marc waren überzeugt, dass jeder Mensch eine innere und eine äußere Erlebniswelt besitzt, die durch die Kunst … … zusammengeführt werden. Außerdem glaubten sie an die Gleichberechtigung aller Kunstformen. Faktisch zählt der Blaue Reiter zum Expressionismus.Kandinsky und Marc gehörten zuerst einer anderen Künstlergruppe an. Sie hieß „Neue Künstlervereinigung München“. Aber besonders Kandinsky hatte … …immer öfter Streit mit den eher traditionell denkenden Mitgliedern der Gruppe wegen seiner sehr abstrakten Malerei und so traten er und Franz Marc 1911 aus. Sie organisierten noch im selben Jahr die erste Blaue-Reiter-Ausstellung, die … … ein großer Erfolg wurde. Die Künstlergruppe „Der Blaue Reiter“ war geboren. Von Anfang an zur Gruppe gehörten auch August Macke und Gabriele Münter, die langjährige Lebensgefährtin von Kandinsky. Sie lebten zusammen in … …Murnau, in der Nähe von Garmisch Partenkirchen im Voralpenland. Ganz in der Nähe, in Sindelsdorf, wohnten Franz und Marie Marc, zu denen sie engen Kontakt hatten. -

Paul Klee, Mar.13-April 2, 1930

Paul Klee, Mar.13-April 2, 1930 Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1930 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1766 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 730 FIFTHAVE NEW YORK BMHanb . PAUL K L E E VyNy-T* MARCH 13 1930 APRIL 2 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 730 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK ACKNOWLEDGMENT The exhibition has been made possible primarily through the generous co-operation of the artist's representatives, The Flechtheim Gallery of Berlin, and the J. B. Neumann Gallery of New York. The following have also generously lent pictures: Mr. Philip C. Johnson, Cleve land; The Gallery of Living Art, New York University; The Weyhe Gallery, New York. Thanks are extended to them on behalf of the Trustees and the Staff of the Museum of Modern Art. TRUSTEES A. CONGER GOODYEAR, PRESIDENT MISS L. P. BLISS, VICE-PRESIDENT MRS. JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., TREASURER FRANK CROWN IN SHI ELD, SECRETARY WILLIAM T. ALDRICH FREDERIC C. BARTLETT STEPHEN C. CLARK MRS. W. MURRAY CRANE CHESTER DALE SAMUEL A. LEWISOHN DUNCAN PHILLIPS MRS. RAINEY ROGERS PAUL J. SACHS MRS. CORNELIUS J. SULIVAN ALFRED H. BARR, JR., Director J ERE ABBOTT, Associate Director 5 Note — On the front cover of this Catalog is a sim plified zinc cut of Klee's Portrait of an Equilibrist. -

Franz Marc Animals Fine Art Pages

Playing Weasels Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1909 Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Franz Marc was a German painter and printmaker that lived from 1880 to 1916. He studied in Munich and in France. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Siberian Sheepdogs Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1910 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Post-Impressionism Interesting Fact: While serving in the German military in World War I, Marc painted tarp covers in various artistic styles, ranging “from Manet to Kandinsky” in hopes of hiding artillery. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Blue Horse I Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Deer in the Snow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Donkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Most of Marc’s work portrays animals in a very stark way, using bold colors. His style caught the attention of the art world. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Monkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Interesting Fact: A “frieze” is a wide horizontal painting or other decoration, often displayed on a wall near the ceiling. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Resting Cows Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com The Yellow Cow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: The style of Expressionism was a modern form of art that began in the early 1900s. -

Call#: NXSSO.A1 T68 2016 ~ 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1-C .,.0

ILLiad TN: 453217 Call#: 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 NXSSO.A 1 T68 2016 1-c~ .,.0 ....... Borrower: FHM Location: Atlanta Library North 4 N PROCESS DATE: 1-c -0.> Lending String: 20161003 -+-> *GSU,DLM,TEU,AMH,CSL,EZC,SUS ~~ Patron: ARIEL IFMCharge .......0 Journal Title: The total work of art : r:/). Maxcost: 25.001FM 1-c foundations, articulations, inspirations I 0.> ~ Shipping Address: ......> Volume: Issue: Interlibrary Loans ~ MonthNear: 2016 University of South Florida ~ Pages: 157-182, 259-272 4202 East Fowler Avenue LIB 121 0.> Tampa, Florida 33620 ~ Article Title: The "Translucent (Not: United States -+-> Transparent)" Gesamtglaswerk r./J. Fax: ::r: ro Imprint: New York: Berghahn Books, 2016. (<: ....... NOTICE: THIS MATERIAL MAY BE PROTECTED Ariel: ody or article exchange {_~ BY COPYRIGHT LAW (TITLE 17, U.S. CODE) 0 0.> d ILL Number: 172025970 Or ship via: ARIEL 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 CHAPTERS (""-••.."" The 11 T ranslucent (Not: Transparent)" Gesamtglaswerk JENNY ANGER runo Taut's Glashaus (Glass house, 1914, Figure 8.1) stood on the east Bern bank of the Rhine River, across from the monumental cathedral of Cologne, for just two years. It was accessible to the public for shorter still: a few weeks in the summer of 1914. The outbreak of war-and the need to gar rison soldiers on the German Werkbund's exhibition grounds-might have darkened this temple of light forever. 1 Despite its brief existence, however, the Glashaus contributed to an ideal that aspired to be as enduring and inspi rational as those of its sister temple on the far shore. Following the German tradition of constructing utopian neologisms out of constitutive parts-the Glashaus, for example, or Richard Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art)-I call this ideal the Gesamtglaswerk (total work of glass). -

NATALIA-GONCHAROVA EN.Pdf

INDEX Press release Fact Sheet Photo Sheet Exhibition Walkthrough A CLOSER LOOK Goncharova and Italy: Controversy, Inspiration, Friendship by Ludovica Sebregondi ‘A spritual autobiography’: Goncharova’s exhibition of 1913 by Evgenia Iliukhina Activities in the exhibition and beyond List of the works Natalia Goncharova A woman of the avant-garde with Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, 28.09.2019–12.01.2020 #NataliaGoncharova This autumn Palazzo Strozzi will present a major retrospective of the leading woman artist of the twentieth- century avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova. Natalia Goncharova will offer visitors a unique opportunity to encounter Natalia Goncharova’s multi-faceted artistic output. A pioneering and radical figure, Goncharova’s work will be presented alongside masterpieces by the celebrated artists who served her either as inspiration or as direct interlocutors, such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. Natalia Goncharova who was born in the province of Tula in 1881, died in Paris in 1962 was the first women artist of the Russian avant-garde to reach fame internationally. She exhibited in the most important European avant-garde exhibitions of the era, including the Blaue Reiter Munich, the Deutsche Erste Herbstsalon at the Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin and at the post-impressionist exhibition in London. At the forefront of the avant- garde, Goncharova scandalised audiences at home in Moscow when she paraded, in the most elegant area of the city with her face and body painted. Defying public morality, she was also the first woman to exhibit paintings depicting female nudes in Russia, for which she was accused and tried in Russian courts. -

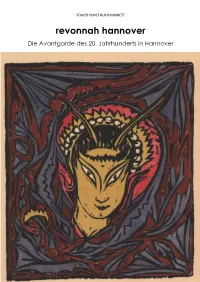

Revonnah Hannover Die Avantgarde Des 20

STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT revonnah hannover Die Avantgarde des 20. Jahrhunderts in Hannover 1 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT Katalog 3 Herbst 2018 Stader Kunst-Buch-Kabinett Antiquariat Michael Schleicher Schützenstrasse 12 21682 Hansestadt STADE Tel +49 (0) 4141 777 257 Email [email protected] Abbildungen Umschlag: Katalog-Nummern 67 und 68; Katalog-Nummer 32. Preise in EURO (€) Please do not hesitate to contact me: english descriptions available upon request. 2 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT 1 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Vorwort). I. Sonderausstellung Max Liebermann Gemälde Handzeichnungen. 1. Oktober - 5. November [1916]. Hannover, Königstr. 8. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1916, ca. 19,8 x 14,5 cm, (16) Seiten, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original-Klammerheftung. Umschlag etwas fleckig, Rückendeckel mit handschriftlichen Zahlenreihen, sonst ein gutes Exemplar. 280,-- Kestnerchronik 1, 29. - Schmied 1 (Abbildung des Umschlages Seite 238). - Literatur: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Hannover, Kunstverein, 1962. - Schmied, Wieland, Wegbereiter zur modernen Kunst, 50 Jahre Kestner Gesellschaft, 1966. - Kestnerchronik, Kestnergesellschaft, Buch 1, 2006. - REVONNAH, Kunst der Avantgarde in Hannover 1912-1933, Sprengel Museum, 2017. 2 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Text). III. Sonderausstellung Willy Jaeckel Gemälde u. Graphik. 17. Dezember 1916 - 17. Januar 1917. Hannover, Königstrasse 8. Zeitgleich mit Walter Alfred Rosam und Ludwig Vierthaler (Verzeichnis auf lose einliegendem Doppelblatt). Verkäufliche Arbeiten mit den gedruckten Preisangaben. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1917, ca. 19,7 x 14,4 cm, (16) Seiten, (4) Seiten Einlagefaltblatt als Ergänzung zum Katalog, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original- Klammerheftung (Klammern oxidiert). Im oberen Bereich alter Feuchtigkeitsschaden; die Seiten sind nicht verklebt. -

The Blue Rider

THE BLUE RIDER 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 1 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 2 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 2 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 HELMUT FRIEDEL ANNEGRET HOBERG THE BLUE RIDER IN THE LENBACHHAUS, MUNICH PRESTEL Munich London New York 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 3 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 4 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 CONTENTS Preface 7 Helmut Friedel 10 How the Blue Rider Came to the Lenbachhaus Annegret Hoberg 21 The Blue Rider – History and Ideas Plates 75 with commentaries by Annegret Hoberg WASSILY KANDINSKY (1–39) 76 FRANZ MARC (40 – 58) 156 GABRIELE MÜNTER (59–74) 196 AUGUST MACKE (75 – 88) 230 ROBERT DELAUNAY (89 – 90) 260 HEINRICH CAMPENDONK (91–92) 266 ALEXEI JAWLENSKY (93 –106) 272 MARIANNE VON WEREFKIN (107–109) 302 ALBERT BLOCH (110) 310 VLADIMIR BURLIUK (111) 314 ADRIAAN KORTEWEG (112 –113) 318 ALFRED KUBIN (114 –118) 324 PAUL KLEE (119 –132) 336 Bibliography 368 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 5 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 6 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 PREFACE 7 The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), the artists’ group formed by such important fi gures as Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, Alexei Jawlensky, and Paul Klee, had a momentous and far-reaching impact on the art of the twentieth century not only in the art city Munich, but internationally as well. Their very particular kind of intensely colorful, expressive paint- ing, using a dense formal idiom that was moving toward abstraction, was based on a unique spiritual approach that opened up completely new possibilities for expression, ranging in style from a height- ened realism to abstraction. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215/842-6353 CONTACT: Katie Ziglar Deb Spears (202) 842-6353 ** Press preview: Wednesday, November 15, 1989 EXPRESSIONIST AND OTHER MODERN GERMAN PAINTINGS AT NATIONAL GAT.T.KRY Washington, D.C., September 18, 1989 Thirty-four outstanding German paintings from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection begin an American tour at the National Gallery of Art, November 19, 1989 through January 14, 1990. Expressionism and Modern German Painting from the Thyssen- Bornemisza Collection contains important examples by artists whose major paintings are extremely rare in this country. The nineteen artists represented in the show include Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Otto Dix, Johannes Itten, Franz Marc, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The intense and colorful works in this exhibition are among the modern paintings Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza has added, along with old master paintings, to the collection he inherited from his father> Baron Heinrich (1875-1947). Expressionism and Modern German Painting, to be seen at three American museums, is selected from the large collection on view at the Baron's home, Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland, through October 29, 1989. It is the first exhibition devoted entirely to the modern German paintings in the collection. -more- expressionism and modern german painting . page two "Comprehensive groupings of expressionism and modern German paintings are extremely rare in American museums and we are pleased to offer a show of this extraordinary caliber here this fall," said J. Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery. The American show has been selected by Andrew Robison, senior curator at the National Gallery.