Gustave Caillebotte 1848 – 1894

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impressionist Adventures

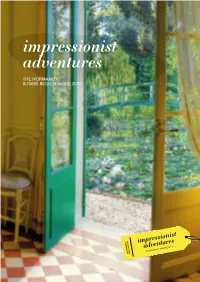

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

Aberystwyth University Gustave Caillebotte's Interiors

Aberystwyth University Gustave Caillebotte’s Interiors: Working Between Leisure and Labor Raybone, Samuel Published in: nonsite.org Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): Raybone, S. (2018). Gustave Caillebotte’s Interiors: Working Between Leisure and Labor. nonsite.org, N/A(26), N/A. [N/A]. https://nonsite.org/article/gustave-caillebottes-interiors Document License CC BY-ND General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 Gustave Caillebotte’s Interiors: Working Between Leisure and Labor ARTICLES ISSUE #26 // BY SAMUEL RAYBONE // NOVEMBER 11, 2018 Born into immense wealth, Gustave Caillebotte nevertheless “compelled himself to labor at painting.”1 In so doing he routinely represented the labor of others, both on the job—as in Les Raboteurs de parquet (g. -

Press Dossier

KEES VAN DONGEN From 11th June to 27th September 2009 PRESS CONFERENCE 11th June 2009, at 11.30 a.m. INAUGURATION 11th June 2009, at 19.30 p.m. Press contact: Phone: + 34 93 256 30 21 /26 Fax: + 34 93 315 01 02 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. PRESENTATION 2. EXHIBITION TOUR 3. EXHIBITION AREAS 4. EXTENDED LABELS ON WORKS 5. CHRONOLOGY 1. PRESENTATION This exhibition dedicated to Kees Van Dongen shows the artist‘s evolution from his student years to the peak of his career and evokes many of his aesthetic ties and exchanges with Picasso, with whom he temporarily shared the Bateau-Lavoir. Born in a suburb of Rotterdam, Van Dongen‘s career was spent mainly in Paris where he came to live in 1897. A hedonist and frequent traveller, he was a regular visitor to the seaside resorts of Deauville, Cannes and Monte Carlo, where he died in 1968. Van Dongen experienced poverty, during the years of revelry with Picasso, and then fame before finally falling out of fashion, a status he endured with a certain melancholy. The exhibition confirms Kees Van Dongen‘s decisive role in the great artistic upheavals of the early 20th century as a member of the Fauvist movement, in which he occupied the unique position of an often irreverent and acerbic portraitist. The virulence and extravagance of his canvases provoked immediate repercussions abroad, particularly within the Die Brücke German expressionist movement. Together with his orientalism, contemporary with that of Matisse, this places Van Dongen at the very forefront of the avant-garde. -

AH 275 PARIS MUSEUMS IES Abroad Paris DESCRIPTION: This

AH 275 PARIS MUSEUMS IES Abroad Paris DESCRIPTION: This course will approach the history of French Art from a chronological perspective, from the 17th century to modern art, as seen in the museums of Paris. Our route will begin at the Louvre with Nicolas Poussin (17th century) and will finish with the avant-garde (Fauvism and Cubism). Along the way, we will visit Neo-Classicism (David), Romanticism (Géricault, Delacroix), the Realists (Courbet, Manet), the Impressionists (Monet, Renoir, Degas), and many others. Each class/visit will be devoted to a work, a historical movement, or a specific artist. Our visits will take us to different types of museums, from the most renowned to the lesser known, from the most traditional to the most original: the large, national museums (Le Louvre, Musée d’Orsay), art collectors’ former houses (Le Musée Jacquemart-Andre, le Musée Marmottan Monet), artist studios (Musée Delacroix, Musee Gustave Moreau), and places of study and production (L’Institut de France, L’ecole Nationale des Beaux-arts). In order to maintain a diverse approach and to benefit from our presence here in Paris, we will devote two classes to locations that have inspired artists. We will give priority to Impressionism, visiting Montmartre (where Renoir painted Le Bal au Moulin de la Galette), and Montparnasse, where the avant- garde found its home in 1910. CREDITS: 3 credits CONTACT HOURS: 45 hours LANGUAGE OF INSTRUCTION: French PREREQUISITES: none METHOD OF PRESENTATION: ● Visits to museums ● Note taking ● Literary texts in chronological -

Realism Impressionism Post Impressionism Week Five Background/Context the École Des Beaux-Arts

Realism Impressionism Post Impressionism week five Background/context The École des Beaux-Arts • The École des Beaux-Arts (est. 1648) was a government controlled art school originally meant to guarantee a pool of artists available to decorate the palaces of Louis XIV Artistic training at The École des Beaux-Arts • Students at the École des Beaux Arts were required to pass exams which proved they could imitate classical art. • An École education had three essential parts: learning to copy engravings of Classical art, drawing from casts of Classical statues and finally drawing from the nude model The Academy, Académie des Beaux-Arts • The École des Beaux-Arts was an adjunct to the French Académie des beaux-arts • The Academy held a virtual monopoly on artistic styles and tastes until the late 1800s • The Academy favored classical subjects painted in a highly polished classical style • Academic art was at its most influential phase during the periods of Neoclassicism and Romanticism • The Academy ranked subject matter in order of importance -History and classical subjects were the most important types of painting -Landscape was near the bottom -Still life and genre painting were unworthy subjects for art The Salons • The Salons were annual art shows sponsored by the Academy • If an artist was to have any success or recognition, it was essential achieve success in the Salons Realism What is Realism? Courbet rebelled against the strictures of the Academy, exhibiting in his own shows. Other groups of painters followed his example and began to rebel against the Academy as well. • Subjects attempt to make the ordinary into something beautiful • Subjects often include peasants and workers • Subjects attempt to show the undisguised truth of life • Realism deliberately violates the standards of the Academy. -

Extrait Du Catalogue

Extrait du catalogue Tarif Public 24/09/2021 www.revendeurs.rmngp.fr Document non contractuel Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées 254-256, rue de Bercy - 75577 Paris cedex 12 - France Tel : +33 (0)1 40 13 48 00 - Fax : +33 (0)1 40 13 44 00 Etablissement public industriel et commercial - APE 9102Z - RCS Paris B692 041 585 - SIRET 69204158500583 - TVA FR11692041585 Sommaire Collections » Louvre, Gangzai Design ... 1 Collections » Louvre, Joconde Céladon ... 2 Collections » Louvre, Liberté guidant le peuple ... 3 Collections » Orsay, Le Parlement ... 6 Collections » Orsay, Les Nymphéas ... 7 Collections » Picasso, Dora Maar ... 7 Collections » Versailles, Dames de la Cour ... 8 Collections » Versailles, Gravure de mode ... 9 Collections » Versailles, Napoléon ... 9 Jeunesse » Arts Plastiques ... 11 Jeunesse » Planches de stickers ... 12 Jeunesse » Jeux & Puzzles ... 12 Jeunesse » Un moment de lecture... ... 12 Cadeaux » Alimentaire ... 15 Cadeaux » Plateaux & Dessous de verre ... 15 Textiles » Pochettes ... 15 Affiches » Affiche 50 x 70 cm ... 16 Affiches » Affiche hors format ... 17 Affiches » Image Luxe 30 x 40 cm ... 17 Affiches » Reproduction 24 x 30 cm à fond perdu ... 18 Carterie » Carte postale 10,5 x 15 cm ... 19 Carterie » Carte postale 10,5 x 15 cm sous Marie-Louise 20 x 25 cm ... 54 Carterie » Carte postale 10,5 x 15 cm sur papier de création arts graphiques (Inuit blanc glacier 400 g) ... 54 Carterie » Carte postale 13,5 x 13,5 cm ... 60 Carterie » Carte postale 13,5 x 13,5 cm sur papier de création arts graphiques (Inuit blanc glacier 400 g) ... 66 Carterie » Carte postale 14 x 20 cm sur papier de création arts graphiques (Inuit blanc glacier 400 g) .. -

The French Art World in the 19Th and 20Th Centuries : Summer

The French Art World in the 19th and 20th centuries : Summer Session Professor: Laure-Caroline Semmer Period: Monday-Wednesday-Thursday 14h-16h30 (unless otherwise indicated) Email: / 06 11 16 87 58 Course Abstract This course traces the artistic contribution to modernity in 19th -century and the first decades of 20th century French art, its utopian dimension, its different achievements and its decline. Since the French Revolution, major works of art, art critics and theorists, and artists themselves contributed to change drastically the artist’s role and the role of the arts. Against the backdrop of the newly established bourgeois, industrialized and modernized society in France, the co-existence of opposite art practices and ideologies as well as the quickly following changes and innovations in successive art-movements, such as realism, impressionism, postimpressionism, cubism, fauvism will be analysed with regard to their respective claim for modernity. Through an examination of form and content distinguishable in works of various artistic disciplines (painting, sculpture, architecture, design), students will critically evaluate artistic language and expression that is representative of modern ideologies. This course will examine the visual arts and will utilize theoretical texts for supportive analysis. Course Objectives: Upon completionSAMPLE of the course the student will be able to: - Distinguish major art movements from Neo-Classicism to Modern Art. - Analyze and contextualize key works of 19th and 20th century French Art. - Demonstrate awareness and understanding of their historical, social and esthetical background. - Have a basic reading of essential art critics and art theories dealing with modernity. - Acquire basic knowledge about the foundations of Modern Art. -

Impressionist Still Life 2001

Impressionist Still Life 2001- 2002 Finding Aid The Phillips Collection Library and Archives 1600 21st Street NW Washington D.C. 20009 www.phillipscollection.org CURATORIAL RECORDS IN THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION ARCHIVES INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION Collection Title: Impressionist Still Life; exhibition records Author/Creator: The Phillips Collection Curatorial Department. Eliza E. Rathbone, Chief Curator Size: 8 linear feet; 19 document boxes Bulk Dates: 1950-2001 Inclusive Dates: 1888-2002 (portions are photocopies) Repository: The Phillips Collection Archives INFORMATION FOR USERS OF THE COLLECTION Restrictions: The collection contains restricted materials. Please contact Karen Schneider, Librarian, with any questions regarding access. Handling Requirements: Preferred Citation: The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington, D.C. Publication and Reproduction Rights: See Karen Schneider, Librarian, for further information and to obtain required forms. ABSTRACT Impressionist Still Life (2001 - 2002) exhibition records contain materials created and collected by the Curatorial Department, The Phillips Collection, during the course of organizing the exhibition. Included are research, catalogue, and exhibition planning files. HISTORICAL NOTE In May 1992, the Trustees of The Phillips Collection named noted curator and art historian Charles S. Moffett to the directorship of the museum. Moffett, a specialist in the field of painting of late-nineteenth-century France, was directly involved with the presentation of a series of exhibitions during his tenure as director (1992-98). Impressionist Still Life (2001-2002) became the third in an extraordinary series of Impressionist exhibitions organized by Moffett at The Phillips Collection, originating with Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir‟s Luncheon of the Boating Party in 1996, followed by the nationally touring Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige, on view at the Phillips in 1998. -

Les Dessins De CAILLEBOTTE @ Hermé, Mai 1989 Editions Hermé 3, Rue Du Regard — 75006 Paris Tél

Les dessins de CAILLEBOTTE @ Hermé, mai 1989 Editions Hermé 3, rue du Regard — 75006 Paris Tél. : (1) 45 49 12 50 ISBN : 2-86665-084-0 Maquette : Jacques Blot JEAN CHARDEAU Les dessins de CAILLEBOTTE fI ktotâ LES DESSINS DE GUSTAVE CAILLEBOTTE par Kirk Varnedoe . our la plupart des gens, l'étiquette ture linéaire, et sur des études de détail soi- Mais Caillebotte utilisa ces méthodes clas- « '« Impressionnisme » suggère un art gneusement assemblées. siques d'une façon très personnelle. En p basé sur une réponse immédiate et construisant délibérément des perspectives spontanée aux impressions fugitives de la cou- Je me rappelle l'émotion que j'ai ressen- inhabituelles telles celles que donnent des pri- leur et de la lumière naturelle. tie, lorsque, grâce à la bienveillante coopé- ses de vue avec un grand angle, Caillebotte Nous attendons de la peinture présentée par ration des descendants de l'artiste, j'ai a su acquérir un sens dramatique original, les impressionnistes aux expositions des découvert les études de perspective et de sil- novateur, avec des premiers plans imposants années 1870 de s'intéresser à ce qui est ins- houettes qui ont préfiguré l'exécution et des perspectives fuyantes. Il a donné à ses tantané et fugitif, et d'être exécutée comme d'oeuvres comme « Rue de Paris ». Ces des- personnages un réalisme particulier par les une rapide esquisse. Le seul peintre qui sins prouvent combien sont injustes les criti- bizarreries des attitudes inhabituelles dans des échappe à cette règle est évidemment Edgar ques de l'époque, qui ont eu tort de suggérer gestes spécifiquement ordinaires, et en parti- Degas. -

Extrait Du Catalogue

Extrait du catalogue Tarif Public 10/10/2021 www.revendeurs.rmngp.fr Document non contractuel Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées 254-256, rue de Bercy - 75577 Paris cedex 12 - France Tel : +33 (0)1 40 13 48 00 - Fax : +33 (0)1 40 13 44 00 Etablissement public industriel et commercial - APE 9102Z - RCS Paris B692 041 585 - SIRET 69204158500583 - TVA FR11692041585 Sommaire Collections » Petit Palais, Rampe d'escalier ... 1 Collections » Louvre, Pyramide Pei ... 1 Collections » Orsay, Art floral ... 2 Collections » Orsay, Le Parlement ... 2 Collections » Orsay, Les Nymphéas ... 2 Collections » Picasso, Dora Maar ... 3 Collections » Picasso, Taureau ... 4 Collections » Jeunesse, Chauveau ... 4 Collections » Jeunesse, Pompon ... 5 Jeunesse » Arts Plastiques ... 6 Jeunesse » Jeux & Puzzles ... 6 Jeunesse » Un moment de lecture... ... 7 Cadeaux » Décoration Maison ... 9 Cadeaux » Art de la Table ... 9 Cadeaux » Plateaux & Dessous de verre ... 9 Cadeaux » Mugs & Bols ... 9 Cadeaux » Bureau ... 10 Textiles » Habillement ... 10 Textiles » Etoles & foulards ... 10 Textiles » Sacs & Tote Bags ... 11 Textiles » Pochettes ... 11 Textiles » Accessoires ... 11 Bijoux » Colliers ... 12 Bijoux » Broches ... 12 Moulages » Art français ... 12 Estampes » Estampes contemporaines ... 14 Estampes » Estampes modernes XXe ... 18 Estampes » Animaux ... 20 Estampes » Architecture & Ornements ... 21 Estampes » Mythologie ... 21 Estampes » Paris & Alentours ... 21 Estampes » Paysages & Marine ... 23 Estampes » Peinture ... 24 Estampes » Portraits ... 24 Estampes » Scènes de genre ... 25 Estampes » Villes & Monuments ... 25 Affiches » Affiche 50 x 70 cm ... 26 Affiches » Affiche 40 x 60 cm (exposition) ... 27 Affiches » Affiche hors format ... 27 Affiches » Image Luxe 30 x 40 cm ... 27 Affiches » Image Luxe 30 x 80 cm ... 28 Affiches » Reproduction 24 x 30 cm à fond perdu .. -

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism National Gallery of Art Teacher Institute 2014

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism National Gallery of Art Teacher Institute 2014 Painters of Modern Life in the City Of Light: Manet and the Impressionists Elizabeth Tebow Haussmann and the Second Empire’s New City Edouard Manet, Concert in the Tuilleries, 1862, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London Edouard Manet, The Railway, 1873, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art Photographs of Baron Haussmann and Napoleon III a)Napoleon Receives Rulers and Illustrious Visitors To the Exposition Universelle, 1867, b)Poster for the Exposition Universelle Félix Thorigny, Paris Improvements (3 prints of drawings), ca. 1867 Place de l’Etoile and the Champs-Elysées Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, 1873, oil on canvas, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Great Boulevards, 1875, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Pont Neuf, 1872, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Collection Hippolyte Jouvin, The Pont Neuf, Paris, 1860-65, albumen stereograph Gustave Caillebotte, a) Paris: A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago, b) Un Balcon, 1880, Musée D’Orsay, Paris Edouard Manet, Le Balcon, 1868-69, oil on canvas, Musée D’Orsay, Paris Edouard Manet, The World’s Fair of 1867, 1867, oil on canvas, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo (insert: Daumier, Nadar in a Hot Air Balloon, 1863, lithograph) Baudelaire, Zola, Manet and the Modern Outlook a) Nadar, Charles Baudelaire, 1855, b) Contantin Guys, Two Grisettes, pen and brown ink, graphite and watercolor, Metropolitan -

Gustave Caillebotte

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preparing students in advance p. 4 Pronunciation guide p. 5 About the exhibition pp. 6–12 Featured artworks pp. 13–28 The Floor Scrapers, 1875 Paris Street, Rainy Day, 1877 A Boating Party, 1877–78 The Rue Halévy, Seen from the Sixth Floor, 1878 At a Café, 1880 Interior, a Woman Reading, 1880 Fruit Displayed on a Stand, c. 1881–82 Sunflowers, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers, c. 1885 3 PREPARING STUDENTS IN ADVANCE We look forward to welcoming your school group to the Museum. Here are a few suggestions for teachers to help to ensure a successful, productive learning experience at the Museum. LOOK, DISCUSS, CREATE Use this resource to lead classroom discussions and related activities prior to the visit. (Suggested activities may also be used after the visit.) REVIEW MUSEUM GUIDELINES For students: • Touch the works of art only with your eyes, never with your hands. • Walk in the museum—do not run. • Use a quiet voice when sharing your ideas. • No photography is permitted in special exhibitions. • Write and draw only with pencils—no pens or markers, please. Additional information for teachers: • Backpacks, umbrellas, or other bulky items are not allowed in the galleries. Free parcel check is available. • Seeing-eye dogs and other service animals assisting people with disabilities are the only animals allowed in the Museum. • Unscheduled lecturing to groups is not permitted. • No food, drinks, or water bottles are allowed in any galleries. • Cell phones should be turned to silent mode while in the Museum. • Tobacco use, including cigarettes, cigars, pipes, electronic cigarettes, snuff, and chewing tobacco, is not permitted in the Museum or anywhere on the Museum's grounds.