Icons, Christ and the Madonna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage Violence, Power and the Director an Examination

STAGE VIOLENCE, POWER AND THE DIRECTOR AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE by Jordan Matthew Walsh Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy. The University of Pittsburgh May 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS & SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jordan Matthew Walsh It was defended on April 13th, 2012 and approved by Jesse Berger, Artistic Director, Red Bull Theater Company Cynthia Croot, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Annmarie Duggan, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Lisa Jackson-Schebetta, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department 2 Copyright © by Jordan Matthew Walsh 2012 3 STAGE VIOLENCE AND POWER: AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE Jordan Matthew Walsh, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This exploration of stage violence is aimed at grappling with the moral, theoretical and practical difficulties of staging acts of extreme violence on stage and, consequently, with the impact that these representations have on actors and audience. My hypothesis is as follows: an act of violence enacted on stage and viewed by an audience can act as a catalyst for the coming together of that audience in defense of humanity, a togetherness in the act of defying the truth mimicked by the theatrical violence represented on stage, which has the potential to stir the latent power of the theatre communion. I have used the theoretical work of Antonin Artaud, especially his “Theatre of Cruelty,” and the works of Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and Sarah Kane in conversation with Artaud’s theories as a prism through which to investigate my hypothesis. -

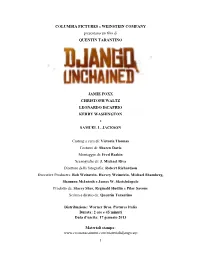

Django Unchained

COLUMBIA PICTURES e WEINSTEIN COMPANY presentano un film di QUENTIN TARANTINO JAMIE FOXX CHRISTOPH WALTZ LEONARDO DiCAPRIO KERRY WASHINGTON e SAMUEL L. JACKSON Casting a cura di: Victoria Thomas Costumi di: Sharen Davis Montaggio di: Fred Raskin Scenografie di: J. Michael Riva Direttore della fotografia: Robert Richardson Executive Producers: Bob Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Michael Shamberg, Shannon McIntosh e James W. Skotchdopole Prodotto da: Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin e Pilar Savone Scritto e diretto da: Quentin Tarantino Distribuzione: Warner Bros. Pictures Italia Durata: 2 ore e 45 minuti Data d’uscita: 17 gennaio 2013 Materiali stampa: www.cristianacaimmi.com/materialidjango.zip 1 DJANGO UNCHAINED Sinossi Ambientato nel Sud degli Stati Uniti due anni prima dello scoppio della Guerra Civile, Django Unchained vede protagonista il premio Oscar® Jamie Foxx nel ruolo di Django, uno schiavo la cui brutale storia con il suo ex padrone, lo conduce faccia a faccia con il Dott. King Schultz (il premio Oscar® Christoph Waltz), il cacciatore di taglie di origine tedesca. Schultz è sulle tracce dei fratelli Brittle, noti assassini, e solo l’aiuto di Django lo porterà a riscuotere la taglia che pende sulle loro teste. Il poco ortodosso Schultz assolda Django con la promessa di donargli la libertà una volta catturati i Brittle – vivi o morti. Il successo dell’operazione induce Schultz a liberare Django, i due uomini scelgano di non separarsi, anzi Schultz sceglie di partire alla ricerca dei criminali più ricercati del Sud con Django al suo fianco. Affinando le vitali abilità di cacciatore, Django resta concentrato su un solo obiettivo: trovare e salvare Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), la moglie che aveva perso tempo prima, a causa della sua vendita come schiava. -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural

HORSE MOTIFS IN FOLK NARRATIVE OF THE SlPERNA TURAL by Victoria Harkavy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ___ ~C=:l!L~;;rtl....,19~~~'V'l rogram Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: ~U_c-ly-=-a2..!-.:t ;LC>=-----...!/~'fF_ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Victoria Harkavy Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland-College Park 2006 Director: Margaret Yocom, Professor Interdisciplinary Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful and supportive parents, Lorraine Messinger and Kenneth Harkavy. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Drs. Yocom, Fraser, and Rashkover, for putting in the time and effort to get this thesis finalized. Thanks also to my friends and colleagues who let me run ideas by them. Special thanks to Margaret Christoph for lending her copy editing expertise. Endless gratitude goes to my family taking care of me when I was focused on writing. Thanks also go to William, Folklore Horse, for all of the inspiration, and to Gumbie, Folklore Cat, for only sometimes sitting on the keyboard. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Interdisciplinary Elements of this Study ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

True Detective Episode Guide Episodes 001–024

True Detective Episode Guide Episodes 001–024 Last episode aired Sunday February 24, 2019 www.hbo.com c c 2019 www.tv.com c 2019 www.hbo.com c 2019 www.tvrage.com c 2019 celebdirtylaundry.com c 2019 www.refinery29.com The summaries and recaps of all the True Detective episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http:// www.hbo.com and http://www.tvrage.com and http://celebdirtylaundry.com and http://www.refinery29.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on February 26, 2019 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.61 Contents Season 1 1 1 The Long Bright Dark . .3 2 Seeing Things . .7 3 The Locked Room . 11 4 Who Goes There . 15 5 The Secret Fate of All Life . 19 6 Haunted Houses . 23 7 After You’ve Gone . 27 8 Form and Void . 31 Season 2 35 1 The Western Book of the Dead . 37 2 Night Finds You . 41 3 Maybe Tomorrow . 43 4 Down Will Come . 47 5 Other Lives . 51 6 Church in Ruins . 53 7 Black Maps and Motel Rooms . 55 8 Omega Station . 59 Season 3 63 1 The Great War and Modern Memory . 65 2 Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye . 67 3 The Big Never . 69 4 The Hour and the Day . 71 5 If You Have Ghosts . 75 6 Hunters in the Dark . 77 7 The Final Country . 79 8 Now Am Found . 81 Actor Appearances 85 True Detective Episode Guide II Season One True Detective Episode Guide The Long Bright Dark Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Sunday January 12, 2014 Writer: Nic Pizzolatto Director: Cary Joji Fukunaga Show Stars: Woody Harrelson (Martin Hart), Matthew McConaughey (Rustin Cohle), Michelle Monaghan (Maggie Hart), Michael Potts (Det. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós-Graduação Em Letras/Inglês E Literatura Correspondente

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE SHAKESPEARE IN THE TUBE: THEATRICALIZING VIOLENCE IN BBC’S TITUS ANDRONICUS FILIPE DOS SANTOS AVILA Supervisor: Dr. José Roberto O’Shea Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras/Inglês e Literatura Correspondente da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento parcial dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS FLORIANÓPOLIS MARÇO/2014 Agradecimentos CAPES pelo apoio financeiro, sem o qual este trabalho não teria se desenvolvido. Espero um dia retribuir, de alguma forma, o dinheiro investido no meu desenvolvimento intelectual e profissional. Meu orientador e, principalmente, herói intelectual, professor José Roberto O’Shea, por ter apoiado este projeto desde o primeiro momento e me guiado com sabedoria. My Shakespearean rivals (no sentido elisabetano), Fernando, Alex, Nicole, Andrea e Janaína. Meus colegas do mestrado, em especial Laísa e João Pedro. A companhia de vocês foi de grande valia nesses dois anos. Minha grande amiga Meggie. Sem sua ajuda eu dificilmente teria terminado a graduação (e mantido a sanidade!). Meus professores, especialmente Maria Lúcia Milleo, Daniel Serravalle, Anelise Corseuil e Fabiano Seixas. Fábio Lopes, meu outro herói intelectual. Suas leituras freudianas, chestertonianas e rodrigueanas dos acontecimentos cotidianos (e da novela Avenida Brasil, é claro) me influenciaram muito. Alguns russos que mantém um site altamente ilegal para download de livros. Sem esse recurso eu honestamente não me imaginaria terminando essa dissertação. Meus amigos. Vocês sabem quem são, pois ouviram falar da dissertação mais vezes do que gostariam ao longo desses dois anos. Obrigado pelo apoio e espero que tenham entendido a minha ausência. -

Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg

NATHALIE DJURBERG & HANS BERG 25 JANUARY – 26 APRIL 2020 Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, It Will End in Stars, 2018, virtual reality. Courtesy of the artist and Acute Art. It Will End in Stars (2018) is an immersive virtual reality experience combining Nathalie Djurberg’s distinctive sculpted figures with black and white charcoal drawings, text, and an un- settling soundtrack by Hans Berg. The work is a continuation of Djurberg’s interest in archetypal landscapes, evoking fairy tales first encountered in childhood. Viewers begin their journey deep in a forest, entering a clearing to discover a wooden cabin. Inside, a wolf sits in front of a glowing fire – the building’s chintz interior undercut by a creeping sense of unease. Hand-written text, which appears hanging in mid-air, conveys the wolf’s thoughts, merging digital technology with an aesthetic closer to silent cinema. He describes the virtual environment as the ‘shadowside’, delivering a confession that merges themes common in Djurberg’s practice; fear, guilt and animalistic impulse. Leipziger Strasse 60 T +49 30 921 062 460 [email protected] D 10117 Berlin www.jsc.art Painstakingly scanned and animated, Djurberg’s creature is responsive, meeting the viewer’s gaze and responding to their movements. The effect is disconcerting; we are uncomfortably aware of our status as watched intruder. Around the room, objects become portals into alternate dimen- sions: a skull becomes a route into a kaleidoscopic environment, while a shadowy enclave of the cabin opens out into a cavernous animated temple. This dream-like vision ends in a sprawling star-scape, removing any sense of time and space through a suggestion of infinity. -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

Newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 190 - September 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 19/06 (Nr. 190) September 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, sein, mit der man alle Fans, die bereits ein lich zum 22. Bond-Film wird es bestimmt liebe Filmfreunde! Vorgängermodell teuer erworben haben, wieder ein nettes Köfferchen geben. Dann Was gibt es Neues aus Deutschland, den ärgern wird. Schick verpackt in einem ed- möglicherweise ja schon in komplett hoch- USA und Japan in Sachen DVD? Der vor- len Aktenkoffer präsentiert man alle 20 auflösender Form. Zur Stunde steht für den liegende Newsletter verrät es Ihnen. Wie offiziellen Bond-Abenteuer als jeweils 2- am 13. November 2006 in den Handel ge- versprochen haben wir in der neuen Ausga- DVD-Set mit bild- und tonmäßig komplett langenden Aktenkoffer noch kein Preis be wieder alle drei Länder untergebracht. restaurierten Fassungen. In der entspre- fest. Wer sich einen solchen sichern möch- Mit dem Nachteil, dass wieder einmal für chenden Presseerklärung heisst es dazu: te, der sollte aber nicht zögern und sein Grafiken kaum Platz ist. Dieses Mal ”Zweieinhalb Jahre arbeitete das MGM- Exemplar am besten noch heute vorbestel- mussten wir sogar auf Cover-Abbildungen Team unter Leitung von Filmrestaurateur len. Und wer nur an einzelnen Titeln inter- in der BRD-Sparte verzichten. Der John Lowry und anderen Visionären von essiert ist, den wird es freuen, dass es die Newsletter mag dadurch vielleicht etwas DTS Digital Images, dem Marktführer der Bond-Filme nicht nur als Komplettpaket ”trocken” wirken, bietet aber trotzdem den digitalen Filmrestauration, an der komplet- geben wird, sondern auch gleichzeitig als von unseren Lesern geschätzten ten Bildrestauration und peppte zudem alle einzeln erhältliche 2-DVD-Sets. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Proquest Dissertations

JUSTICE AT 24 FRAMES PER SECOND: LAW AND SPECTACLE IN THE REVENGE FILM By Robert John Tougas B.A. (Hons.), LL.B., B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario (May 15,2008) 2008, Robert John Tougas Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43498-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43498-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Julie Burton

Julie Burton Fairytale Characteristics in Medieval Romances Doctoral thesis completed but not submitted, owing to the death of the author This thesis represents the state of completion the author attained before her death in March 2010. It was her final wish that it be made available to the widest possible scholarly circulation. All queries regarding this should be directed to her husband: Mr Simon Burton, 51 Double Row, Charlestown, Fife, KY11 3EJ Tel: 01383 872847 Email: [email protected] The bibliography was posthumously prepared from the footnotes by Dr Lynne Blanchfield (queries to [email protected]). Page 1 of 249 INTRODUCTION From the viewpoint of the twenty-first century, Middle English romance can be a problematic genre. Its fantastic events, stock characters, repetitive structures and contrived endings seem to belong with the fairytale of the nursery rather than with the 1 serious literature of the adult world. Stylistically, so many romances do little to counter this impression with formulaic words and phrases expressing simplistic emotions and commonplace sentiments. Yet Middle English romance was an enduring genre, popular over five hundred years or more. Although Chaucer was famously disparaging about the verse romances in his burlesque „Sir Thopas‟, many survive in the collections of, or indeed were commissioned by, worldly men, important and successful in their time. Clearly this raises a question: why are the romances, once so popular, unpalatable to the reading public of today? Any response to this question would of course be complex, not least because the romance genre notoriously embraces a range of greatly differing works.