THE EU ZOO INQUIRY 2011 an Evaluation of the Implementation and Enforcement of the EC Directive 1999/22, Relating to the Keeping of Wild Animals in Zoos ENGLAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

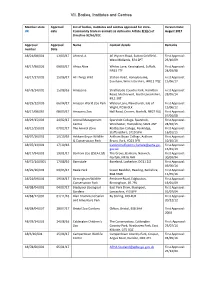

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

A Stella Year the Park Is Celebrating Its 50Th Anniversary in 2020

2020 WILD TALKwww.cotswoldwildlifepark.co.uk New baby White Rhino Stella cuddles up to her mum Ruby Photo: Rory Carnegie Rory Photo: A Stella Year The Park is celebrating its 50th Anniversary in 2020. We hope to continue to inspire future Ruby and Stella walked out of the stall, giving generations to appreciate the beauty of the lucky visitors a glimpse of a baby White Rhino natural world. 2019 was a great year with Soon after the birth, Ruby and her new calf record visitor numbers, TV appearances, lots walked out of the stall into the sunshine of the of baby animals and a new Rhino calf. yard, giving a few lucky visitors a glimpse of a baby White Rhino less than two hours old. ighlights of the year included the Stella is doing well and Ruby has proved once Park featuring on BBC’s Springwatch again to be an exceptional mother. Having Hprogramme, with our part in the White another female calf is really important for the Storks’ UK re-introduction project. Then in European Breeding Programme of this iconic Astrid October, BBC Gardeners’ World featured the but endangered species. Park and presenter Adam Frost sang the praises OUR 6 RHINO CALVES of our gardens. To top off the year, Ruby gave White Rhinos have always been an important 1. Astrid born 1st July 2013, birth to our sixth Rhino calf in as many years, species at the Park, which was founded by John moved to Colchester Zoo. named “Stella”! Heyworth (1925-2012) in 1970. He had a soft spot 2. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

Zsl Annual Review / Welcome

THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2013 ZSL ANNUAL REVIEW / WELCOME Welcome The President and Director General of the Zoological Society of London introduce our review of the year and look back on the highlights of 2013. As President of the Zoological From shedding new light on the Society of London (ZSL), it is my endangered Ethiopian wolf to great pleasure to introduce our revealing the dramatic extent of 2013 annual review. It was an prehistoric bird extinctions in the extremely successful year for our Pacific and investigating disease Zoos at London and Whipsnade, transmission between bats as well as for our scientific and humans, 2013 was another research and conservation work in the field. March 2013 busy year for our world-class Institute of Zoology. The saw the grand opening of Tiger Territory at ZSL London introduction of a new scientific research theme in 2013, Zoo, home to our magnificent pair of Sumatran tigers. looking at people, wildlife and ecosystems, highlights This landmark exhibit showcases our commitment to one of the core truths underlying ZSL’s mission: that we saving these critically endangered big cats from extinction. humans are an integral part of the natural world, with Throughout this review you will read more about the enormous influence over the animals with which we tremendous efforts put in by our staff and supporters share the planet. Engaging people with wildlife and to make Tiger Territory a reality. conservation is a vital part of the work we do, and our Another exciting launch in 2013 was United for Wildife, Zoos, high-profile research, busy events programme our alliance with six other leading field-based conservation and engagement work with communities at home and organisations to address the world’s greatest wildlife threats. -

EAZA NEWS Zoo Nutrition 4

ZOO NUTRITION EAZANEWS 2008 publication of the european association of zoos and aquaria september 2008 — eaza news zoo nutrition issue number 4 8 Feeding our animals without wasting our planet 10 Sustainability and nutrition of The Deep’s animal feed sources 18 Setting up a nutrition research programme at Twycross Zoo 21 Should zoo food be chopped? 26 Feeding practices for captive okapi 15 The development of a dietary review team 24 Feeding live prey; chasing away visitors? EAZA Zoonutr5|12.indd 1 08-09-2008 13:50:55 eaza news 2008 colophon zoo nutrition EAZA News is the quarterly magazine of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) issue 4 Managing Editor Jeannette van Benthem ([email protected]) Editorial staff for EAZA News Zoo Nutrition Issue 4 Joeke Nijboer, Andrea Fidgett, Catherine King Design Jantijn Ontwerp bno, Made, the Netherlands Printing Drukkerij Van den Dool, Sliedrecht, the Netherlands ISSN 1574-2997. The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. Printed on TREE-FREE paper bleached without chlorine and free from acid who is who in eaza foreword EAZA Executive Committee Although nourishing zoo animals properly and according chair Leobert de Boer, Apenheul Primate Park vice-chair Simon Tonge, Paignton Zoo secretary Eric Bairrao Ruivo, Lisbon Zoo treasurer Ryszard Topola, Lodz Zoo to their species’ needs is a most basic requirement to chair eep committee Bengt Holst, Copenhagen Zoo chair membership & ethics maintain sustainable populations in captivity, zoo and committee Lars Lunding Andersen, Copenhagen Zoo chair aquarium committee aquarium nutrition has been a somewhat underestimated chair legislation committee Jurgen Lange, Berlin Zoo Ulrich Schurer, Wuppertal Zoo science for a long time. -

Concepts in the Care and Welfare of Captive Elephants J

REVIEW: ELEPHANTS CONCEPTS IN CARE AND WELFARE IN CAPTIVITY 63 Int. Zoo Yb. (2006) 40: 63–79 © The Zoological Society of London Concepts in the care and welfare of captive elephants J. VEASEY Woburn Safari Park, Woburn, Bedfordshire MK17 9QN, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Zoos are duty bound to maintain a high standard of challenges facing zoos both from an welfare for all animals for which they are respons- ible. For elephants, this represents a greater chal- animal husbandry and a public perception lenge than for many other species; their sheer size, perspective. This document is not sophisticated social life, high level of intelligence and designed to be a formula for elephant wel- large behavioural repertoire, combined with their fare in captivity because there are still too origins in tropical and subtropical climates mean that replicating the physical, social and environ- many un-answered questions, rather it is mental requirements needed for a high standard of intended as a discussion of some of the welfare in captivity is a significant challenge. This is concepts relating to captive elephant wel- compounded by the difficulties in measuring welfare generally, and specifically for animals such as ele- fare, which it is hoped, might encourage phants within zoo environments. Evidence does exist people from a variety of viewpoints to relating to the longevity, reproductive success and consider elephant welfare in a different the health status of captive elephants which suggests way. I will not go into the issue of whether that their management is not at as high a standard as it is for many other species kept in zoos, and that or not elephants should be in captivity elephant welfare is likely to be compromised as a because this would be a not inconsider- result. -

Supplement - 2016

Green and black poison dart frog Supplement - 2016 Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Living Coasts & Newquay Zoo Supplement - 2016 Index Summary Accounts 4 Figures At a Glance 6 Paignton Zoo Inventory 7 Living Coasts Inventory 21 Newquay Zoo Inventory 25 Scientific Research Projects, Publications and Presentations 35 Awards and Achievements 43 Our Zoo in Numbers 45 Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Living Coasts & Newquay Zoo Bornean orang utan Paignton Zoo Inventory Pileated gibbon Paignton Zoo Inventory 1st January 2016 - 31st December 2016 Identification IUCN Status Arrivals Births Did not Other Departures Status Identification IUCN Status Arrivals Births Did not Other Departures Status Status 1/1/16 survive deaths 31/12/16 Status 1/1/16 survive deaths 31/12/16 >30 days >30 days after birth after birth MFU MFU MAMMALIA Callimiconidae Goeldi’s monkey Callimico goeldii VU 5 2 1 2 MONOTREMATA Tachyglossidae Callitrichidae Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus LC 1 1 Pygmy marmoset Callithrix pygmaea LC 5 4 1 DIPROTODONTIA Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia EN 3 1 1 1 1 Macropodidae Pied tamarin Saguinus bicolor CR 7 3 3 3 4 Western grey Macropus fuliginosus LC 9 2 1 3 3 Cotton-topped Saguinus oedipus CR 3 3 kangaroo ocydromus tamarin AFROSORICIDA Emperor tamarin Saguinus imperator LC 3 2 1 subgrisescens Tenrecidae Cebidae Lesser hedgehog Echinops telfairi LC 8 4 4 tenrec Squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus LC 5 5 Giant (tail-less) Tenrec ecaudatus LC 2 2 1 1 White-faced saki Pithecia pithecia LC 4 1 1 2 tenrec monkey CHIROPTERA Black howler monkey Alouatta caraya NT 2 2 1 1 2 Pteropodidae Brown spider monkey Ateles hybridus CR 4 1 3 Rodrigues fruit bat Pteropus rodricensis CR 10 3 7 Brown spider monkey Ateles spp. -

Review of Zoos' Conservation and Education Contribution

Review of Zoos’ Conservation and Education Contribution Contract No : CR 0407 Prepared for: Jane Withey and Margaret Finn Defra Biodiversity Programme Zoos Policy Temple Quay House Bristol BS1 6EB Prepared by: ADAS UK Ltd Policy Delivery Group Woodthorne Wergs Road Wolverhampton WV6 8TQ Date: April 2010 Issue status: Final Report 0936648 ADAS Review of Zoos’ Conservation and Education Contribution Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank in particular the zoos, aquariums and animal parks that took part in the fieldwork and case studies. We are also grateful to members of the Consultation Group and the Steering Group for their advice and support with this project. The support of Tom Adams, Animal Health, is also acknowledged for assistance with sample design. Project Team The ADAS team that worked on this study included: • Beechener, Sam • Llewellin, John • Lloyd, Sian • Morgan, Mair • Rees, Elwyn • Wheeler, Karen The team was supported by the following specialist advisers: • BIAZA (British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums); and • England Marketing - provision of telephone fieldwork services I declare that this report represents a true and accurate record of the results obtained/work carried out. 30 th April 2010 Sam Beechener and Mair Morgan (Authors’ signature) (Date) 30 th April 2010 John Llewellin (Verifier’s signature) (Date) Executive Summary Executive Summary Objectives The aims of this project were to collect and assess information about the amount and type of conservation and education work undertaken by zoos in England. On the basis of that assessment, and in the light of the Secretary of State’s Standards of Modern Zoo Practice (SSSMZP) and the Zoos Forum Handbook (2008 - including the Annexes to Chapter 2), the project will make recommendations for: • minimum standards for conservation and education in a variety of sizes of zoo; and • methods for zoo inspectors to enable them to assess zoo conservation and educational activities. -

Press Release Issued – 25 August 2016 Top Ten Native

PRESS RELEASE ISSUED – 25 AUGUST 2016 TOP TEN NATIVE SPECIES BENEFITTING FROM ZOOS & AQUARIUMS As the State of Nature prepares to release its 2016 report that warns Britain’s wildlife is facing a “crisis” with more than 120 species at risk of extinction due to intensive farming, the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA) reveals the top ten native species being supported by its members. BIAZA’s Director, Dr Kirsten Pullen, says, “Most people equate zoos and aquariums to holding and protecting animals that are exotic to the UK. Certainly, during their visits, the public expect to see a wonderful range of creatures from all around the world. What is not well known is that not only do modern zoos do considerable amounts of conservation work globally, they also provide their skills and resources to help wildlife at home.” Native species conservation efforts are often collaborative with BIAZA members setting up projects with other BIAZA zoos and aquariums as well as wildlife charities and NGOs. Modern zoological establishments provide husbandry expertise, support breeding programmes and help raise funds to ensure Britain’s wildlife has the best chance of survival in the face of increased pressures from climate change, agriculture and persecution. 1. Hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius) Over the last 100 years the hazel dormouse has become extinct in almost half the UK counties where it used to thrive. Loss of woodland and hedgerows are the main cause of the decline, and this endangered animal is now protected by law. In 1993 Natural England initiated a Species Recovery Programme, and today dormouse reintroduction work is coordinated by the Peoples’ Trust for Endangered Species. -

Provisional Checklist and Account of the Mammals of the London Borough of Bexley

PROVISIONAL CHECKLIST AND ACCOUNT OF THE MAMMALS OF THE LONDON BOROUGH OF BEXLEY Compiled by Chris Rose BSc (Hons), MSc. 4th edition. December 2016. Photo: Donna Zimmer INTRODUCTION WHY PROVISIONAL? Bexley’s mammal fauna would appear to be little studied, at least in any systematic way, and its distribution is incompletely known. It would therefore be premature to suggest that this paper contains a definitive list of species and an accurate representation of their actual abundance and geographical range in the Borough. It is hoped, instead, that by publishing and then occasionally updating a ‘provisional list’ which pulls together as much currently available information as can readily be found, it will stimulate others to help start filling in the gaps, even in a casual way, by submitting records of whatever wild mammals they see in our area. For this reason the status of species not thought to currently occur, or which are no longer found in Bexley, is also given. Mammals are less easy to study than some other groups of species, often being small, nocturnal and thus inconspicuous. Detecting equipment is needed for the proper study of Bats. Training in the live-trapping of small mammals is recommended before embarking on such a course of action, and because Shrews are protected in this regard, a special licence should be obtained first in case any are caught. Suitable traps need to be purchased. Dissection of Owl pellets and the identification of field signs such as Water Vole droppings can help fill in some of the gaps. Perhaps this document will be picked up by local students who may be looking for a project to do as part of their coursework, and who will be able to overcome these obstacles.