Corvus Review || Issue 11 (Fall/Winter) 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blitz - the Rock and Roll Magazine

blitz - the rock and roll magazine for thinking people wednesday about me ELECTRIC PRUNES INTERVIEW BlitzMagazine United States Blitz Magazine was founded in 1975. Editor/Publisher Michael McDowell moved operations to Los Angeles, California in 1980. Please check the How To Reach Us link for current contact information. View my complete profile previous posts BITS AND PIECES - NEWS ABOUT YOUR FAVORITE ARTISTS... THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME (REISSUES AND ANTHOLOG... THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME (NEW RELEASES) By Mich... NEVER HAD IT BETTER: In the past year and a half, Electric Prunes co-founder HOW TO REACH US and front man, James Lowe (pictured above, earlier this year) has weathered the passing of bandmate and bassist Mark Tulin, as well as his own quadruple bypass surgery, and is now preparing for the next phase of the legendary first generation garage band's career with the release of a new Electric Prunes live CD, recorded in Stockholm. Lowe discusses this and more with Blitz Editor/Publisher Michael McDowell below (Click on above image to enlarge). REWIRED: THE ELECTRIC PRUNES’ JAMES LOWE DISCUSSES HIS JOURNEY FROM TRAGEDY TO TRIUMPH “Since the death of our bass player and co-founder of the band, Mark Tulin last year, we have been in a shambles. I guess you don't expect anyone to die. But Mark was so full of life and such an important part of the band, it was as if one of the legs had been sawed off a three legged stool. We miss Mark daily. The band must go on, and we know that is what Mark would have wanted.” So said Electric Prunes front man, James Lowe in a statement on the fourteenth of May. -

Surf Report the Lives of a Persecuted People in and Accessible Latin-Style Music

THURSDAY, JULY 22, 2004 Volume 3, Issue 216 FREE Santa Monica Daily Press A newspaper with issues DAILY LOTTERY SUPER LOTTO Malibu schools want to split from SM 41 40 12 43 14 Meganumber: 12 Breaking up may be hard to do for Malibu residents, solely to the split. “We’re just a dent district, despite added admin- Jackpot: 7 Million second thought, and we’ve always istrative costs. FANTASY 5 who feel like a ‘second thought’ to district “It’s a very cohesive communi- 13 19 27 34 39 been a second thought.” BY JOHN WOOD the 13,000-student Santa Monica- Made up of mostly parents, the ty and it seems to me that, if they DAILY LOTTO formed their own district, it would Daytime: 9 4 2 Daily Press Staff Writer Malibu Unified School District. Malibu Unified School Team, Evening: 8 8 6 They cite the 30 miles between LLC, has established a board of generate even more community DAILY DERBY MALIBU — Residents of this Malibu and school district head- directors and meets regularly. support for the schools that they 1st: 05 California Classic well-heeled, rural community are quarters, and said that distance is a They also have commissioned a have now,” said Griffin, who was 2nd: 04 Big Ben spearheading a formal push to prime reason for change. 27-page study outlining nine state paid $2,500 for the study. 3rd: 06 Whirl Win “It’s an interesting phenome- RACE TIME: 1:48.16 break away from the local school “They figure that we’ll just take mandates for establishing their district, taking with them more care of ourselves,” said Susan own school district. -

Whats Purple and Goes Buzz Buzz?: a Conversation with the Electric Prunes’ James Lowe

A Quinn Martin Production Subscribe to feed ABOUT Whats Purple and Goes Buzz Buzz?: A Conversation with The Electric Prunes’ James Lowe Sam Tweedle: The Electric Prunes are one of the great 60’s groups that sat on the fringes of SAM TWEEDLE – THE POP CULTURE ADDICT the rock n’ roll scene. Sam Tweedle is a writer and pop James Lowe: Well, I was culture addict who has been surprised that anybody knew entertaining and educating fans of about us when we came back the pop culture journey for a decade. and started playing again. His writing has been featured in The National Post, CNN.com, and Sam: Really? Why is that? Filmfax magazine. James: I think essentially THE POP CULTURE ADDICT AND because the people that we were FRIENDS! involved with made us feel that what we did, when we did it, was Visit the gallery to see more photos a failure. So I never admitted that of Sam Tweedle and his close I was in The Electric Prunes for a encounters! lot of years. [The label] expected us to be like The Beatles and sell a lot of records, but we didn’t do “I was surprised that anybody knew about us when we came that. I’m kind of surprised that we back and started playing again…. I never admitted that I was have fans. in The Electric Prunes for a lot of years.” Sam: Well I always put The Electric Prunes in the same league with some of the era’s cult favourites, like The Velvet Underground or The New Colony Six. -

Tmr-6.2-January-2021

The Magnolia Review Volume 6, Issue 2 January 2021 Editor-in-Chief Suzanna Anderson Editor-in-Chief Suzanna Anderson Editor: David Anthony Sam Editor: Aretha Lemon Note: “Skimming the Water” by Donna Emerson was first published by COG magazine, Spring, 2020. “After Winter Rains” by Donna Emerson was first published by COG magazine, Spring 2020. “Riding Bareback” by Donna Emerson was reprinted by Pudding Magazine, and originally placed in her second poetry collection, “Beside the Well,” editor Cherry Grove Collections, December 2019. “The Kippah Drawer” by Robert Granader was first published by JewishFiction.net, March 2020. “Dickinson and Triumph” by Robin Long was first published by 8 Poems Every Month. “Marx Eulogy” by Mark A. Murphy was first published by New Reader Magazine. “He Who Has the Youth” by Mark A. Murphy was first published by New Reader Magazine. “Red” by Charlotte Edwards was first published in Spill Words. “Afterwards” by Hanna Komar was first published by the Blue Nib. Welcome to the twelfth issue of The Magnolia Review! We publish art, photography, poetry, comics, creative nonfiction, flash fiction, experimental work, and fiction. The Magnolia Review publishes previously unpublished work and reprints of previously published work. We publish two issues a year, and we accept submissions year-round. The issue will be available online on January 15 and July 15. While The Magnolia Review will not have physical copies at this time, the editors may compile a print version if funds become available. Sales of physical copies are part of fundraising efforts to pay for two free contributor copies and mailing costs for each contributor. -

Journeying Fall 2020 Issue 17

Red Wolf Journal Fall 2020 Journeying Irene Toh, Editor 1 Copyright © 2020 by Red Wolf Editions Contributors retain copyright on their own poems. Cover artwork: John William Waterhouse, Ulysses and the Sirens, 1891 No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews giving due credit to the authors. 2 Journeying Is it lack of imagination that makes us come to imagined places, not just stay at home? Or could Pascal have been not entirely right about just sitting quietly in one's room? Continent, city, country, society: the choice is never wide and never free. And here, or there... No. Should we have stayed at home, wherever that may be? —Elizabeth Bishop Ah…the lure of seeing the world. A cornucopia of sights, sounds and tastes for one’s senses awaits the traveler. Beyond the sensory experiences does travel change the traveler? What is its romance? What are the experiences that translate to pleasure, or discomfort? There’re many Journey stories. In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy travels to the magical land of Oz, before returning to Kansas after a magical adventure; in Journey to the West, a Buddhist monk travelled to the western regions of Central Asia and India to obtain the sutras. Accompanied by his three colorful disciples, he encountered many demons who covetted his flesh in exchange for immortality; in the end the monk and his disciples succeeded in their quest; in The Odyssey, Odysseus had taken 10 years to get home to Ithaca, surviving the Lotus-eaters, the Cyclops, the witch goddess Circe, the Sirens, the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis and finally a shipwreck. -

NEW RELEASE for the Week of January 29, 2021 PRIORITIES & HIGHLIGHTS >> Pre-Order Now!

NEW RELEASE for the week of January 29, 2021 PRIORITIES & HIGHLIGHTS >> Pre-Order Now! DECEMBERISTS "Live Home Library Vol. (YOUTH AND 843563132449 LP 1 (2LP) 8-11-09 Royal Oak, MI" February 5 street date. Extremely limited exclusive Decemberist live 2LP. Limited edition one time only pressing. Recorded at Royal Oak Music Theatre in Michigan during the Hazards Of Love tour (2009). The first volume in the Decemberists' Live Home Library series, from the band’s own label — Youth and Beauty Brigade. Vinyl exclusive, not available on streaming services. Mixed by Hazards of Love co-producer/mixer Tucker Martine. Packaging details: 140-gram Double LP on limited edition black vinyl, custom wide-spine jacket / Etched Vinyl D-Side / 24” fold-out insert with oral history and photos of the tour from the band. GUIDED BY VOICES "Propeller" (SCAT) SCAT49 LP/ /CASS/ CD March 19 street date. "Propeller" was the fifth album by Guided By Voices, and was intended to be the group's last. Released as a limited edition of 500 LPs in 1992, the album featured handmade covers and blank labels to keep expenses as low as possible. Their other albums hadn’t sold much, why would this one? As fate would have it, the band wound up releasing an album chock full of gems Pollard had stockpiled, and for the first time sounded distinctly like the band that fans have since come to love. "Propeller" also marks the return of Tobin Sprout to the GBV fold, along with an increased songwriting presence. "Propeller" is a hell of a ride, and remains one of the most important albums in the band's discography. -

Oldiemarkt Magazin

EUR 7,10 DIE WELTWEIT GRÖSSTE MONATLICHE 01/08 VINYL -/ CD-AUKTION Januar Tommy James & The Shondells: Bubblegum? Poprock! Powered and designed by Peter Trieb – D 84453 Mühldorf Ergebnisse der AUKTION 350 Hier finden Sie ein interessantes Gebot dieser Auktion sowie die Auktionsergebnisse Anzahl der Gebote 2.518 Gesamtwert aller Gebote 40.341,00 Gesamtwert der versteigerten Platten / CD’s 21.873,00 Höchstgebot auf eine Platte / CD 710,00 Highlight des Monats Dezember 2007 2LP - Spectrum - Milesago - Harvest SHDW 50/51 - AU - M- / M- So wurde auf die Platte / CD auf Seite 19, Zeile 12 geboten: Mindestgebot EURO 18,00 Progressiver Rock aus Australien gehört Bieter 1 - 3 18,11 - 19,50 zu den begehrtesten Untergruppen des progressiven Rock allgemein. Bieter 4 - 5 20,99 - 21,13 Bands vom 5. Kontinent wie Buffalo, La - Bieter 6 8 23,73 - 25,00 De Das, Kahvas Jute oder Missing Links - erzielen seit langem sehr hohe Preise. In dieses Gebiet passt auch Spectrum aus Bieter 9 - 10 31,01 - 31,50 Australien. Bieter 11 - 12 45,11 - 48,80 Wie man sehen kann, ist das Mindestgebot für dieses Doppel-Album sehr zurückhaltend angesetzt, zumal die Qualität sehr ansprechend ist. Deswegen ist es kein Wunder, dass das Höchstgebot weit darüber liegt. Am überraschendsten ist die hohe Zahl der Bieter, die die eingangs geäußerte Behauptung unterstreicht. Bieter 13 51,80 Sie finden Highlight des Monats ab Juni 1998 im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Werden Sie reich durch OLDIE-MARKT – die Auktionszahlen sprechen für sich ! Software und Preiskataloge für Musiksammler bei Peter Trieb – D84442 Mühldorf – Fax (+49) 08631 – 162786 – eMail [email protected] Kleinanzeigenformulare WORD und EXCEL im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Schallplattenbörsen Oldie-Markt 1/08 3 Plattenbörsen 2007/8 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. -

Ken Williams of the Electric Prunes at Page 1 of 7

Interview with Ken Williams of The Electric Prunes at www.thepsychedelicguitar.com Page 1 of 7 thepsychedelicguitar.com is honored to present a few words with Ken Williams of the The Electric Prunes circa 1967. Ken is at left. http://thepsychedelicguitar.com/williams.htm 22/02/2007 Interview with Ken Williams of The Electric Prunes at www.thepsychedelicguitar.com Page 2 of 7 Here is a guy laid up recovering from back surgery and he E-answers some questions. Is that dedication to his fans and the music or what? Thepsychedelicguitar.com thanks Ken for his words, his years of music, and wishes him a speedy recovery and best of luck with all his endeavors! Was there a particular moment that guitar music or music in general grabbed you, shook you to the core, and said "This is your life's path"? There was no particular moment where I (knew) music was what I wanted to do with my life. While I have always been interested in lots of things, playing music was at the very top. When I first started playing it was the power of the music that attracted me. Turning up the amps and playing good old rock and roll was the high I like the best. It was the best way I knew for me to express myself. Would you talk a little about the scene that birthed the Prunes, and bands you shared stages with. The band started out with Mark Tulin, myself and another guitar player. We were all guitar players, with no bass or drums. -

Carl Winderl 49 the Plot - Murali Kamma 57 Singing Bird- Kendra Clark 61 the Slate - Dr

COO WEE SCOO WEE 2019 Managing Editor Sally Emmons Fiction Editor Emily Dial-Driver Poetry Editor Mary Mackie Student Editor Jake Brillhart ISSN 1541-0846 We would like to give special thanks to everyone at the RSU Print Shop and Kara White, without whom this commando publication would not exist. Upon publication, all rights to works contained herin are retained by their contributors. Disclaimer: We are not responsible for the potty language herein, nor the seedy characters who seem to be like someone you know, nor the offensive art that is certain to shock your sensibilities. If you are considering legal action, what do you say we avoid the lawyers and just settle the whole thing with a game of high stakes poker? Rogers State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, or verteran status. II | Cooweescoowee COO WEE SCOO WEE 2019 Cooweescoowee | III iv | Cooweescoowee Contents Prose 2 Accident - Rod Martinez 6 The Black Box - Kara White 15 Little Ships - Sandra Scofield 21 Miller Redbird Is Going to Hell - Autumn Forkiller 24 Play the Ball, Don't Let It Play You - Carl Winderl 49 The Plot - Murali Kamma 57 Singing Bird- Kendra Clark 61 The Slate - Dr. Irving A. Greenfield 72 Turbulence - Marlene Olin Poetry 79 Autumn - Ivanov Reyes 80 Can't Stop - Jack Cooper 81 Dead Heat - Ivanov Reyes 83 Greener Grass - Jim Peterson 84 The Secret to Perfect Contentment - Gaylor Brewer 85 Tornado - George Longenecker 87 Turn - Jack Cooper 88 Walnut Hulls - Mark Tulin Art 91 Darion Grant 93 Spencer Plumlee 96 Sean Tyler 98 Bridget Williams Contributors' 101 Notes Cooweescoowee | v PPRR OOSSEE ACCIDENT Rod Martinez hen I finally opened my eyes, the blue hue across the Tampa Bay Whorizon was gone. -

The Electric Prunes the Electric Prunes Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Electric Prunes The Electric Prunes mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Electric Prunes Country: US Released: 1967 Style: Garage Rock, Psychedelic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1885 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1510 mb WMA version RAR size: 1209 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 651 Other Formats: DTS XM MP3 MP1 AIFF ADX AA Tracklist Hide Credits I Had Too Much To Dream (Last Night) A1 2:55 Written-By – Tucker*, Mantz* Bangles A2 2:27 Written-By – J. Walsh* Onie A3 2:43 Written-By – Tucker*, Mantz* Are You Lovin' Me More (But Enjoying It Less) A4 2:21 Written-By – Tucker*, Mantz* Train For Tomorrow A5 2:27 Written-By – Spagnola*, Williams*, Tulin*, Ritter*, Lowe* Sold To The Highest Bidder A6 2:16 Written-By – Tucker*, Mantz* Get Me To The World On Time B1 2:30 Written-By – Tucker*, Jones* About A Quarter To Nine B2 2:07 Written-By – Dubin*, Warren* The King Is In The Counting House B3 2:00 Written-By – Tucker*, Mantz* Luvin' B4 2:03 Written-By – Tulin*, Lowe* Try Me On For Size B5 3:00 Written-By – Tucker*, Jones* Tunerville Trolley B6 2:34 Written-By – Tucker*, Mantz* Credits Arranged By [Strings And Brass], Conductor – Perry Botkin Jr. Art Direction – Ed Thrasher Bass Guitar, Piano, Organ – Mark Tulin Drums, Percussion – Preston Ritter Engineer [Chief Electrical] – Richie Podolor* Lead Guitar – Ken Williams Painting – Stan Leong Photography By – Jane McCowan Producer – Dave Hassinger Technician [Asst. Electrician] – Bill Cooper Vocals, Autoharp, Electric Guitar, Tambourine – Jim Lowe* Vocals, Rhythm Guitar – Weasel* Notes Stereo tri-colored ''steamboat'' Reprise label with variation in producer credit (see images - no Perry Botkin credit in pink area of label) and slightly different runout etching. -

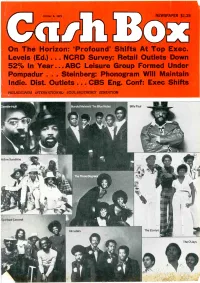

On the Horizon: 'Profound' Shifts at Top Exec

October 6, 1973 NEWSPAPER $1.25 On The Horizon: 'Profound' Shifts At Top Exec. Levels (Ed.) NCRD Survey: Retail Outlets Down 52% In Year ...ABC Leisure Group Formed Under Pompadur...Steinberg: Phonogram Will Maintain Indie. Dist. Outlets ...CBS Eng. Conf: Exec Shifts PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL: SOUL -BROTHERLY SENSATION Yeflow Sunshine The Three Degrees Spiritual Concept Boston i rings America aSecond Revolution: Aerosmith andTheir New Sin66reamOn:' the way Aerosmith has conquered Boston has been absolutely astounding. It began with their single, "Dream On." For five consecutive weeks, it had number -one phones on WVBF-FM. It's now No. 2 on WMEX and has been in the Top 10 there for .ur weeks. In the same four weeks it's gone from hitbound to o. 3 on WRKO. In nearby ?rovidence it's 6 at WPRO and 3 at WICE. And it's getting play at all the FM rockers in the area. But a record as big as "Dream On" can't be confined to one region. So bes_des Hartford and Albany, it's also on in Detroit (No. 25 right away), in Cincinnati, in Houston, in Columbus, in Chicago, in Tacoma and Sacramento; and it's picking up more stations and cities every day. The album has sold more than 20,000 copies in Boston alone. And it's spreading so well, it's now climbing the national charts. Coinciding with the spread of the single and the album, there's a gigantic national tour with Mott the Hoople,insuring that Aerosmith's powerful music will be ringing in every small town and big city in the country. -

Blogcritics Music (Wes Britton)

October 15, 2014 Music Review: The Blues Magoos – ‘Psychedelic Resurrection’ Very arguably, the four American bands that best exemplified the “psychedelic/garage/proto-punk” sound of the 1960s that have tried to renew their presence in the 21st century have been The Electric Prunes, Strawberry Alarm Clock, Sky Saxon of The Seeds, and The Blues Magoos. Back in the day, each were essentially one-and-a- half-hit wonders as each had one signature Top Ten hit with less successful follow-up singles. In recent years, all four of these bands have tried to capitalize on past glories in different ways. The Prunes continued to issue new albums of new material, notably 2004’s Feedback. Before his death on June 25, 2009, Sky “Sunlight Saxon” had maintained a long musical career and was about to go on a new tour booked with the Prunes while working with Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins. Corgan also played live with Mark Weitz of Strawberry Alarm Clock (and the now-late Prunes bassist Mark Tulin) in his Sky Saxon tribute supergroup Spirits in the Sky later in 2009. SAC had become an on-and-off again touring outfit before their first new album since 1969 was released, 2012’s Wake Up Where You Are. In this case, the collection wasn’t really new as every track was a re-recording of old SAC album cuts. Both the Prunes and SAC honored the passing of Saxon by doing new covers of his better known songs, namely “Pushing Too Hard” and “Mr. Farmer.” Now, The Blues Magoos have also gone beyond reuniting for stage performances and also issued a new album, their first in 40 years.