Words Into Movement: the Ballet As Intersemiotic Translation Karen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbora Kohoutková

BARBORA KOHOUTKOVÁ Barbora Kohoutková started ballet training at a very early age. She was chosen at the age of 4 by a pre-ballet school of the National Theater in Prague and got accepted to the Prague Dance Conservatory when she was 10 years old. Barbora started her professional career at the age of 17 in Helsinki as a Principal Dancer with the Finnish National Ballet (1996-2002). Before becoming a guest principal dancer she worked with the Bavarian State Ballet – Munich (2002-2003), Boston Ballet (2003-2004) and Hamburg Ballet-John Neumeier (2004-2008). In her career she has danced the most important roles of almost the entire classical repertoire in its original form and in productions by Ben Stevenson, Natalia Makarova, Rudolf Nureyev, Vladimir Bourmeister, Sylvie Guillem, Wayne Eagling, Toer van Schayk, Bruce Marks, Frederick Ashton, Mikhail Fokine… Besides the classical repertoire she also performed in choreographies by George Balanchine, Jiri Kylian, John Cranko, John Neumeier, Jorma Uotinen, Sir Kenneth MacMillan, Heinz Spoerli, Mark Morris… As a guest artist she has been performing in Essen, Helsinki, Milano, Moscow, Munich, Prague, Rome, St. Petersburg, Tokyo (World Ballet Festival 2002 and 2004), … Sadly, due to injuries, she had to cut short her beautiful career at the early age of 28. After having undergone multiple surgeries and stoically enduring much physical suffering, Barbora had to retire from the stage and began a rewarding career as a Ballet Master and teacher, occasionally still performing as a guest Principal. During the season 2009- 2010 she worked as Ballet Master at the National Theater in Prague. -

New National Theatre, Tokyo 2019/2020 Season

PRESS RELEASE (FEB 2019) NEW NATIONAL THEATRE, TOKYO NEW NATIONAL THEATRE, TOKYO 2019/2020 SEASON BALLET & DANCE THE NATIONAL BALLET OF JAPAN New National Theatre, Tokyo (NNTT) announced the 2019/2020 Ballet & Dance Season, the final season under the Artistic Director, Noriko OHARA, which features 38 performances of 6 ballet works including 5 full-length narrative ballet, and 11 performances of 3 dance pieces. The Final Season for Noriko OHARA as Artistic Director of Ballet and Dance at the New National Theatre, Tokyo Noriko OHARA became the Ballet Mistress of the company in 1999, Assistant Director in 2010 before assumed office as the Artistic Director in September 2014. During these 20 years ever since the company was founded, she has nurtured and led the dancers for The National Ballet of Japan to become the leading company in Japan. This season's line-up sums up this company's best works thus far. The season will open in October with Kenneth MACMILLAN's "Romeo and Juliet", an exemplar of the dramatic ballet tradition. This will be followed by "Manon" in February and March. Both works will showcase the company's expressive richness and depth. Christmas season will feature Wayne EAGLING's "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King". Technically a very demanding piece, this dreamy fairy tale has real visual appeal which audiences of all ages will enjoy. Then, our "New Year Ballet" will feature what has been called "music for the eyes" in the form of George BALANCHINE's "Serenade", as well as pas de deux from "Raymonda" and "Le Corsaire". -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

English National Ballet Emerging Dancer

English National Ballet Emerging Dancer Sadler’s Wells, London Tuesday 7 May 2019 Performance at 7.30pm Tickets: £12- £30 Box office: 020 7845 9300 and ballet.org.uk/emerging Celebrating its tenth year, English National Ballet’s Emerging Dancer competition will be held at Sadler’s Wells on Tuesday 7 May 2019. Through this ‘highly anticipated annual event’ [Pointe Magazine], English National Ballet recognises the excellence of its artists. Selected by their peers, six of the company's most promising dancers perform in front of an eminent panel of expert judges, before one receives the 2019 Emerging Dancer Award. The recipients of the People's Choice Award, selected by members of the public, and the Corps de Ballet Award, acknowledging the work on and off-stage of a member of the Corps de Ballet, will also be revealed. Emerging Dancer is a key part of English National Ballet’s commitment to developing and nurturing talent within the Company and is generously supported by Graeme and Sue Sloan. Last year’s Emerging Dancer Award winner, Daniel McCormick has since performed the role of Nutcracker in the Christmas favourite, the Pas de Trois and Spanish dance in Swan Lake and Lescaut in Manon. The 2019 finalists are: Alice Bellini Bellini trained at La Scala Ballet School and Royal Ballet Upper School before joining English National Ballet as an Artist of the Company in 2017. One of her career highlights to date was dancing the pas de deux in Aszure Barton’s Fantastic Beings. Bellini was voted the 2018 People’s Choice Award winner at last year’s Emerging Dancer competition. -

Barbora Kohoutková

BARBORA KOHOUTKOVÁ Barbora Kohoutková started ballet training at a very early age. She was chosen at the age of 4 by a pre-ballet school of the National Theater in Prague and got accepted to the Prague Dance Conservatory when she was 10 years old. Barbora started her professional career at the age of 17 in Helsinki as a Principal Dancer with the Finnish National Ballet (1996-2002). Before becoming a guest principal dancer she worked with the Bavarian State Ballet – Munich (2002-2003), Boston Ballet (2003-2004) and Hamburg Ballet-John Neumeier (2004-2008). In her career she has danced the most important roles of almost the entire classical repertoire in its original form and in productions by Ben Stevenson, Natalia Makarova, Rudolf Nureyev, Vladimir Bourmeister, Sylvie Guillem, Wayne Eagling, Toer van Schayk, Bruce Marks, Frederick Ashton, Mikhail Fokine… Besides the classical repertoire she also performed in choreographies by George Balanchine, Jiri Kylian, John Cranko, John Neumeier, Jorma Uotinen, Sir Kenneth MacMillan, Heinz Spoerli, Mark Morris… As a guest artist she has been performing in Essen, Helsinki, Milano, Moscow, Munich, Prague, Rome, St. Petersburg, Tokyo (World Ballet Festival 2002 and 2004), … Sadly, due to injuries, she had to cut short her beautiful career at the early age of 28. After having undergone multiple surgeries and stoically enduring much physical suffering, Barbora had to retire from the stage and began a rewarding career as a Ballet Master and teacher, occasionally still performing as a guest Principal. During the season 2009- 2010 she worked as Ballet Master at the National Theater in Prague. -

Barbora Kohoutková

Barbora Kohoutková PLACE OF BIRTH: Czech Republic, in Prague EDUCATION: Prague Dance Conservatory OTHER EDUCATION: Since 2009 Gyrotonic and Gyrokinesis certified instructor ENGAGEMENTS: 1996-2002 Finnish National Ballet 2002-2003 Bavarian State Ballet 2003-2004 Boston Ballet 2004-2008 Hamburg Ballet-John Neumeier 2009- 2010 Ballet Master at the National Theater in Prague 2009 International Guest Dancer and Teacher 2009 Owner and instructor of GYROTONIC and GYROKINESIS in Art of Movement Studio in Prague 2013-2014 Aalto Ballet Essen COMPETITIONS, AWARDS: Bronze medal 1994 in Bordeaux Gold medal National Ballet Competition 1994 in Brno Silver medal 1994 in Varna Grand Prix 1994 in Paris Prix espèces 1995 in Lausanne Gold medal and Grand Prix 1995 in Helsinki Gold medal and Grand Prix 1996 in New York Fazer Prize 2000 in Helsinki 2002 Philip Morris Best Artist Award in Helsinki REPERTORY: Ben Stevenson Cinderella - Cinderella Pierre Lacotte La Sylphide - La Sylphide John Cranko Romeo and Juliet – Juliet Onegin -Tatiana, Olga Natalia Makarova after Marius Petipa La Bayadère – Nikija Rudolf Nureyev The Sleeping Beauty - Aurora; Vladimir Bourmeister The Swan Lake - Odette-Odile, Pas de quatre and the big swans George Balanchine Serenade Heinz Spoerli The Midsummer Night's Dream – Titania Jorma Utonien Ballet Pathétique - The Blue Ballerina Sylvie Guillem Giselle – Gisele Javier Torres after Petipa The Sleeping Beauty – Aurora Kenneth MacMillan Manon – Manon Wayne Eagling and Toer van Schayk The Nutcracker and the Mouse King – Clara George Balanchine -

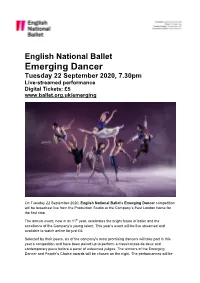

Emerging Dancer Tuesday 22 September 2020, 7.30Pm Live-Streamed Performance Digital Tickets: £5

English National Ballet Emerging Dancer Tuesday 22 September 2020, 7.30pm Live-streamed performance Digital Tickets: £5 www.ballet.org.uk/emerging On Tuesday 22 September 2020, English National Ballet’s Emerging Dancer competition will be broadcast live from the Production Studio at the Company’s East London home for the first time. The annual event, now in its 11th year, celebrates the bright future of ballet and the excellence of the Company’s young talent. This year’s event will be live streamed and available to watch online for just £5. Selected by their peers, six of the company's most promising dancers will take part in this year’s competition and have been paired up to perform a classical pas de deux and contemporary piece before a panel of esteemed judges. The winners of the Emerging Dancer and People’s Choice awards will be chosen on the night. The performances will be accompanied by live music performed by members of the English National Ballet Philharmonic. This year will see Ivana Bueno and William Yamada perform a pas de deux from Talisman, Emily Suzuki and Victor Prigent perform a pas de deux from Satanella and Carolyne Galvao and Angel Maidana perform a piece from Diana and Acteon. The contemporary section will see the couples perform three brand-new original works, created especially for the event. Ballet Black dancer and choreographer Mthuthuzeli November has created a piece for Ivana and William, ENB First Artist and Associate Choreographer Stina Quagebeur is creating for Emily and Victor and ENB Lead Principal Jeffrey Cirio is choreographing for Carolyne and Angel. -

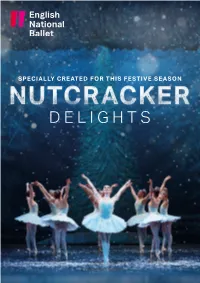

Nutcracker Delights

SPECIALLY CREATED FOR THIS FESTIVE SEASON DELIGHTS I A word from Tamara Rojo Welcome to Nutcracker Delights. I am And, finally, thank you to each of you joining us delighted that we are back on stage at the here for this festive celebration. We are so very This programme was designed for English London Coliseum and that we are once again happy to be able to share this space with you National Ballet’s planned season of Nutcracker able to share our work, live in performance, with again. I hope that you enjoy the performance. President Delights at the London Coliseum from you all. 17 December 2020 — 3 January 2021. Dame Beryl Grey DBE The extraordinary circumstances of 2020 have Chair As London moved into Tier 4 COVID-19 changed the way all of us work and live, and restrictions with the subsequent cancellation Sir Roger Carr I believe more strongly than ever in the power of all scheduled performances of Nutcracker Artistic Director of the arts to provide inspiration, shared Delights, the Company decided to film and Tamara Rojo CBE experience, hope, and solace. Tamara Rojo CBE share online, for free, a recording of this Artistic Director What a pleasure to mark our return to live specially adapted production as a gift to our Executive Director English National Ballet performance by continuing a Christmas fans at the close of our 70th Anniversary year. Patrick Harrison tradition we have held dear for 70 years. We have performed a version of Nutcracker Chief Operating Officer After a year that has been so difficult for so every year since the Company was founded, Grace Chan many, I am thrilled that we are able to bring and were determined to continue this much- Music Director some festive magic back to the stage. -

Programme Calendar

PROGRAMME CALENDAR Dear Reader, First and foremost, let me allay any fears that the anniversary of Shakespeare’s dates that should be marked on the calendar in red letters. Our 120 Hungarian artists will also be joined in song by names birth in 2014 passed us by here at the Opera House. It’s just that we had other like Gruberova, D’Arcangelo, Herlitzius, Kampe, Kwangchul, Watson, Tómasson, Konieczny, Neil, Chacón-Cruz, Valenti, things to do: the festival of the Strauss repertoire that was many years in the Maestri, Ataneli and Demuro, while top domestic conductors and their world-renowned peers will be passing the baton making and the exploration of the theme of Faust, for instance. Now that the to star names like Plasson, Pido, Badea and Steinberg, and the 2nd Iván Nagy International Ballet Gala will once again 400th anniversary of the extraordinarily multi-faceted playwright is approaching, welcome the greats of the global ballet scene – this is because, ever since the times of Erkel and Mahler, the Hungarian State the opportunity has arisen for Hungary’s most prestigious cultural institution to Opera has proclaimed the joyful place among equals occupied by Hungarian culture. mobilise its enormous creative powers in service of exploring the remarkably broad literature of the Shakespearean universe. Broken down into figures, the 2015/2016 season of the Hungarian State Opera will see 500 full-scale performances with 33 new productions and 45 from the repertoire, a total of 100 concerts, chamber performances, gala and other events, some 200 This will not be a commemoration of a death; how could it be? We come to pay children’s programmes, 600 tours of the building and more than 1,100 ambassadorial presentations. -

Narrative Aspects of Kenneth Macmillan's Ballet the Invitation

DOCTORAL THESIS Narrative Aspects of Kenneth MacMillan’s Ballet The Invitation de Lucas Olmos, Maria Cristina Award date: 2017 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Narrative Aspects of Kenneth MacMillan’s Ballet The Invitation by Cristina de Lucas BA Law, BA English and Literature, MA Ballet Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Dance University of Roehampton 2016 To my father and to the memory of my mother, with love. ABSTRACT: The British choreographer Kenneth MacMillan (1929-1992) has a prominent place in the narrative tradition of the Royal Ballet. As a major storyteller in the history of the company, his ballets with intense, dramatic stories are an important part of the dance heritage of British ballet. This thesis focuses on one of MacMillan’s first narrative achievements, the one-act ballet The Invitation (1960), and studies the main thematic concerns and stylistic strategies that it deploys. -

Top Performances of Opera, Music and Dance - Nytimes.Com 11/5/14 11:12 AM

Top Performances of Opera, Music and Dance - NYTimes.com 11/5/14 11:12 AM http://nyti.ms/1wDB3Ko INTERNATIONAL ARTS | SPECIAL REPORT: FRONT ROW CENTER Arts Guide Top Performances of Opera, Music and Dance Compiled by CHRISTOPHER D. SHEA OCT. 29, 2014 Highlights of the performance calendars at the world’s major opera, dance and music halls through December. Opera and ballet Milan Teatro Alla Scala teatroallascala.org The British director Deborah Warner — who set a 2001 Glyndebourne production of Beethoven’s “Fidelio” in a prison camp — will bring a new production of the work to the opera house from Dec. 10 to 23. The production is the final opera that Daniel Barenboim will conduct in his current role as music director. The theater will open its ballet season in December with a new rendering of “The Nutcracker” featuring two of the company’s star performers, Roberto Bolle and Maria Eichwald. Amsterdam Dutch National Opera operaballet.nl Benedict Andrews, the irreverent Australian director who paired Isabelle Huppert and Cate Blanchett in a recent production of Jean Genet’s “The Maids” in New York, will direct a new production of “La Bohème” here in December. Though primarily a theater director, Mr. Andrews has staged several daring opera productions in recent years, including a video-heavy take on Monteverdi’s “The Return of Ulysses” in London that framed the protagonist as a shell- shocked war veteran. The company will also revive popular productions of the ballets “Swan Lake” and “Cinderella” and the opera “Lohengrin.” http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/30/arts/international/top-performances-of-opera-music-and-dance.html?_r=1 Page 1 of 6 Top Performances of Opera, Music and Dance - NYTimes.com 11/5/14 11:12 AM London Royal Opera House roh.org.uk From Nov. -

ENB Annual Review 2017-2018

Annual Review 2017–2018 Contents 4 About English National Ballet 30 ENB Philharmonic 6 A message from our Artistic Director 32 Nurturing Talent 8 A message from our Chairman 36 Reaching Audiences 10 A message from our Executive Director 40 Engagement 12 Highlights 44 Support 14 Artistic Programme Review 48 Financial Performance 22 Artistic Programme Credits 50 Looking Forward 24 Artistic Programme Awards 52 ENB Board & Advisors 26 ENB Dancers 55 ENB Staff English National Ballet Artists as Snowflakes in Nutcracker © Laurent Liotardo 2 3 About English National Our ambition is great ballet for everyone. Our Mission Our Objectives Ballet We bring world-class classical ballet to the – To present productions of classical ballet widest possible audience – delighting them of the highest quality within England and with the traditional and inspiring them with around the world; the new. We aspire to be the United Kingdom’s most exciting and creative ballet company. – To offer access to the widest possible audience through affordable pricing and Our Vision attractive repertoire in a variety of venues including theatres, schools, festivals and Under the leadership of Artistic Director digital platforms; Tamara Rojo, English National Ballet stands for artistic excellence and creativity. – To inspire, enlighten and uplift the public We are a world-class organisation; through performances, events, interaction flexible, collaborative, and enthusiastically and experience; engaging with our audiences. We celebrate the tradition of great classical ballet while – To develop the art form of ballet by embracing change, evolving the art form commissioning new choreography, for future generations and encouraging design, and musical composition as well audiences to deepen their engagement.