Jirapat Tatsanasomboon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana 1.2 Valmiki Ramayana‘s Importance – In The Words Of Valmiki 1.3 Need for selecting the problem from the point of view of Educational Leadership 1.4 Leadership Lessons from Valmiki Ramayana 1.5 Morality of Leaders in Valmiki Ramayana 1.6 Rationale of the Study 1.7 Statement of the Study 1.8 Objective of the Study 1.9 Explanation of the terms 1.10 Approach and Methodology 1.11 Scheme of Chapterization 1.12 Implications of the study CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION Introduction ―The art of education would never attain clearness in itself without philosophy, there is an interaction between the two and either without the other is incomplete and unserviceable.‖ Fitche. The most sacred of all creations of God in the human life and it has two aspects- one biological and other sociological. If nutrition and reproduction maintain and transmit the biological aspect, the sociological aspect is transmitted by education. Man is primarily distinguishable from the animals because of power of reasoning. Man is endowed with intelligence, remains active, original and energetic. Man lives in accordance with his philosophy of life and his conception of the world. Human life is a priceless gift of God. But we have become sheer materialistic and we live animal life. It is said that man is a rational animal; but our intellect is fully preoccupied in pursuit of materialistic life and worldly pleasures. Our senses and objects of pleasure are also created by God, hence without discarding or condemning them, we have to develop ( Bhav Jeevan) and devotion along with them. -

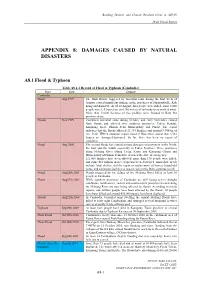

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

The Creative Choreography for Nang Yai (Thai Traditional Shadow Puppet Theatre) Ramakien, Wat Ban Don, Rayong Province

Fine Arts International Journal, Srinakharinwirot University Vol.14 issue 2 July - December 2010 The Creative Choreography for Nang Yai (Thai traditional shadow puppet theatre) Ramakien, Wat Ban Don, Rayong Province Sun Tawalwongsri Abstract This paper aims at studying Nang Yai performances and how to create modernized choreography techniques for Nang Yai by using Wat Ban Don dance troupes. As Nang Yai always depicts Ramakien stories from the Indian Ramayana epic, this piece will also be about a Ramayana story, performed with innovative techniques—choreography, narrative, manipulation, and dance movement. The creation of this show also emphasizes on exploring and finding methods of broader techniques, styles, and materials that can be used in the production of Nang Yai for its development and survival in modern times. Keywords: NangYai, Thai traditional shadow puppet theatre, Choreography, Performing arts Introduction narration and dialogues, dance and performing art Nang Yai or Thai traditional shadow in the maneuver of the puppets along with musical puppet theatre, the oldest theatrical art in Thailand, art—the live music accompanying the shows. is an ancient form of storytelling and entertainment Shadow performance with puppets made using opaque, often articulated figures in front of from animal hide is a form of world an illuminated backdrop to create the illusion of entertainment that can be traced back to ancient moving images. Such performance is a combination times, and is believed to be approximately 2,000 of dance and puppetry, including songs and chants, years old, having been evolved through much reflections, poems about local events or current adjustment and change over time. -

The Transformation of Thai Khon Costume Concept to High-End Fashion Design

THE TRANSFORMATION OF THAI KHON COSTUME CONCEPT TO HIGH-END FASHION DESIGN By Miss Hu JIA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2020 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University - โดย MissHU JIA วทิ ยานิพนธ์น้ีเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรปรัชญาดุษฎีบณั ฑิต สาขาวิชาศิลปะการออกแบบ แบบ 1.1 ปรัชญาดุษฎีบัณฑิต(หลักสูตรนานาชาติ) บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ปีการศึกษา 2563 ลิขสิทธ์ิของบณั ฑิตวทิ ยาลยั มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร THE TRANSFORMATION OF THAI KHON COSTUME CONCEPT TO HIGH-END FASHION DESIGN By Miss Hu JIA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2020 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University Title THE TRANSFORMATION OF THAI KHON COSTUME CONCEPT TO HIGH-END FASHION DESIGN By Hu JIA Field of Study DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Advisor Assistant Professor JIRAWAT VONGPHANTUSET , Ph.D. Graduate School Silpakorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Dean of graduate school (Associate Professor Jurairat Nunthanid, Ph.D.) Approved by Chair person (Professor Eakachat Joneurairatana ) Advisor (Assistant Professor JIRAWAT VONGPHANTUSET , Ph.D.) Co advisor (Assistant Professor VEERAWAT SIRIVESMAS , Ph.D.) External Examiner (Professor Mustaffa Hatabi HJ. Azahari , Ph.D.) D ABST RACT 60155903 : Major DESIGN -

Digital Transformation Stories

Huawei Enterprise e.huawei.com Yue B No. 13154 09/2017 ICT INSIGHTS Yang Xiaoling, “The CPIC digital strategy aims to innovate business models by leveraging technical advantages. CPIC is walking the road Vice President and to digital transformation, and we will continue working with Huawei to provide customers with convenient, high-quality Chief Digital Officer, CPIC { insurance services.” “We decided to build an enterprise private cloud platform and use cloud infrastructure to support our Li Zhihong, core business systems such as ERP and CRM. Huawei has provided us with a series of ICT infrastructure Information Management Department, solutions, such as FusionCube, that fully meet our business development needs and conform to our Digital COFCO Coca-Cola Beverages Ltd. { ICT transformation strategy. We are looking forward to further cooperation with Huawei.” Transformation “In terms of products and solutions, Huawei responds to customer requirements very fast and is highly efficient in terms of product Qi Wei, optimization. After the feedback is sent to R&D, measures are quickly taken to create an optimized version. At the same time, in the cooperation IT Planning Director, Organization process, Dongfeng also acquired valuable management experience from many of Huawei’s outstanding projects. We now use this knowledge Information Department, Dongfeng Motor Group Stories { in our own internal project processes. That’s why we believe the benefits we reaped from cooperating with Huawei are huge.” in the New ICT Era Liu Jianming, “Digital transformation paves the way for more robust Smart Grids, making our life better. Deputy Director of the Power Informatization Study Committee, Huawei is willing and expected to play a bigger role in digital transformation of electric power China Society for Electrical Engineering { systems in all countries and regions across the globe.” “Huawei had clearly done its homework and demonstrated a deep understanding of what we were doing with Hadoop. -

April 2018 04月份

Follow China Intercontinental Press Us on Advertising Hotline WeChat Now 城市漫步珠 国内统一刊号: 三角英文版 that's guangzhou that's shenzhen CN 11-5234/GO APRIL 2018 04月份 that’s PRD 《城市漫步》珠江三角洲 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 11th Floor South Building, Henghua lnternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing http://www.cicc.org.cn 社长 President: 陈陆军 Chen Lujun 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 Circulation: 李若琳 Li Ruolin Editor-in-Chief Matthew Bossons Shenzhen Editor Adam Robbins Guangzhou Editor Daniel Plafker Shenzhen Digital Editor Bailey Hu Senior Staff Writer Tristin Zhang Digital Editor Katrina Shi National Arts Editor Erica Martin Contributors Lena Gidwani, Bryan Grogan, Mia Li, Kheng Swe Lim, Benjamin Lipschitz, Erica Martin, Noelle Mateer, Dominic Ngai, Katrina Shi, Alexandria Williams, Dominique Wong HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 传真 : Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Rm 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125 传真 : 020-8357 3859 - 816 Shenzhen 深圳联络处 深圳市福田区彩田路星河世纪大厦 C1-1303 C1-1303, Galaxy Century Building, Caitian Lu, Futian District, Shenzhen 电话 : 0755-8623 3220 传真 : 0755-6406 8538 Beijing 北京联络处 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 G9 室 邮政编码 -

Intersections Between Capitalist Commodification of Thai K-Pop and Buddhist Fandoms" (2021)

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-21-2021 Sattha, Money and Idols: Intersections Between Capitalist Commodification of Thai -popK and Buddhist Fandoms Pornpailin Meklalit [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Meklalit, Pornpailin, "Sattha, Money and Idols: Intersections Between Capitalist Commodification of Thai K-pop and Buddhist Fandoms" (2021). Master's Projects and Capstones. 1174. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/1174 This Project/Capstone - Global access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sattha, Money and Idols: Intersections Between Capitalist Commodification of Thai K-pop and Buddhist Fandoms Pornpailin (Pauline) Meklalit APS 650: Capstone Project Professor Brian Komei Dempster May 21, 2021 Abstract This study investigates the cultural, economic, and spiritual meanings, as well as the goals of activities carried out by both the K-pop fandom (specifically fans of EXO and NCT) and Buddhist devotees in Thailand—and their considerable degree of overlap. While Thai Buddhism is revered, K-pop fandom is stigmatized as an extreme, problematic form of behavior. -

Ramayan Ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu Way of Life and the Contribution of Hindu Women, Amongst Others

Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) Mahila Shibir 2020 East and South Midlands Vibhag FOREWORD INSPIRING AND UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE In an era of mass consumerism - not only of material goods - but of information, where society continues to be led by dominant and parochial ideas, the struggle to make our stories heard, has been limited. But the tides are slowly turning and is being led by the collaborative strength of empowered Hindu women from within our community. The Covid-19 pandemic has at once forced us to cancel our core programs - which for decades had brought us together to pursue our mission to develop value-based leaders - but also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate in other, more innovative ways. It gives me immense pride that Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) have set a new precedent for the trajectory of our work. As a follow up to the successful Mahila Shibirs in seven vibhags attended by over 500 participants, 342 Mahila sevikas came together to write 411 articles on seven different topics which will be presented in the form of seven e-books. I am very delighted to launch this collection which explores topics such as: The uniqueness of Bharat, Ramayan ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu way of life and The contribution of Hindu women, amongst others. From writing to editing, content checking to proofreading, the entire project was conducted by our Sevikas. This project has revealed hidden talents of many mahilas in writing essays and articles. We hope that these skills are further encouraged and nurtured to become good writers which our community badly lacks. -

Beautiful Northern Thailand

Tel : +47 22413030 | Epost :[email protected]| Web :www.reisebazaar.no Karl Johans gt. 23, 0159 Oslo, Norway Beautiful Northern Thailand Turkode Destinasjoner Turen starter TTSN Thailand Bangkok Turen destinasjon Reisen er levert av 15 dager Bangkok Fra : NOK 15 641 Oversikt There’s a reason this trip was the tour that started it all, and still remains one of the most popular. Discover Northern Thailand, a lush adventure destination that takes you to the heart of what it means to be Intrepid. Experience the chaotic metropolis of bustling Bangkok, trek among the hillside villages near Chiang Rai, drift down the River Kwai in Kanchanaburi and see the historic temples of the Siam Kingdom. With welcoming hospitality, local experiences, mouth-watering cooking classes and plenty of free time to travel at your own pace, come along and see why Beautiful Northern Thailand was, and still is, a benchmark for all other Intrepid adventures. Reiserute Bangkok Sa-wat dee! Welcome to Thailand. Thailand's bustling capital, Bangkok is famous for its tuk tuks, khlong boats and street vendors serving up delicious Thai food. Your adventure begins with a welcome meeting at 6 pm tonight. Bangkok has so much to offer those with time to explore, so perhaps arrive a day or so early and take a riverboat to Chinatown and explore the crowded streets, uncover the magnificent Grand Palace and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, wander down the tourist mecca of Khao San Road, or indulge in some Thai massage. After the meeting tonight, why not get some of your newfound travel pals together for a street food crawl. -

Khōn: Masked Dance Drama of the Thai Epic Ramakien Amolwan Kiriwat

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2001 Khōn: masked dance drama of the Thai epic Ramakien Amolwan Kiriwat Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Kiriwat, Amolwan, "Khōn: masked dance drama of the Thai epic Ramakien" (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 631. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/631 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. KHON: MASKED DANCE DRAMA OF THE THAI EPIC RAMAKIEN BY Amolwan Kiriwat B.A. Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 1997 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Theatre) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2001 Advisory Committee: Sandra E. Hardy, Associate Professor of Theatre, Advisor Thomas J. Mikotowicz, Associate Professor of Theatre Marcia J. Douglas, Assistant Professor of Theatre KHON: MASKED DANCE DRAMA OF THE THAI EPIC RAMAKIEN By Amolwan Kiriwat Thesis Advisor: Dr. Sandra E. Hardy An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Theatre) May, 2001 This thesis will analyze and document khon, which is a masked dance drama, and the Ramakien, which is the Thai epic. This thesis will present the history and structure of khon and show how it is used to present the story of the Ramakien. -

Bodh Gayā in the Cultural Memory of Thailand

Eszter Jakab REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European -

Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors

About the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors The transformation of transport corridors into economic corridors has been at the center of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program since 1998. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted this Assessment to guide future investments and provide benchmarks for improving the GMS economic corridors. This Assessment reviews the state of the GMS economic corridors, focusing on transport infrastructure, particularly road transport, cross-border transport and trade, and economic potential. This assessment consists of six country reports and an integrative report initially presented in June 2018 at the GMS Subregional Transport Forum. About the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program The GMS consists of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, the People’s Republic of China (specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1992, with assistance from the Asian Development Bank and building on their shared histories and cultures, the six countries of the GMS launched the GMS Program, a program of subregional economic cooperation. The program’s nine priority sectors are agriculture, energy, environment, human resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade facilitation. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining