Tripta Chandola Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ward Wise List of Sector Officers, Blos & Blo Supervisors, Municipal

WARD WISE LIST OF SECTOR OFFICERS, BLOS & BLO SUPERVISORS, MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, GURUGRAM Sr. Constit Old P S Ward Sector Officer Mobile No. New Name of B L O Post of B L O Office Address of B L O Mobile No Supervisior Address Mobile No. No. uenc No No. P S No 1 B 15 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 15 Nirmala AWW Pawala Khushrupur 9654643302 Joginder Lect. HIndi GSSS Daultabad 9911861041 (Jahajgarh) 2 B 26 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 26 Roshni AWW Sarai alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 3 B 28 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 28 Anand AWW Choma 9582167811 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 4 B 29 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 29 Rakesh Supervisor XEN Horti. HSVP Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 5 B 30 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 30 Pooja AWW Sarai alawardi 9899040565 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 6 B 31 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 31 Santosh AWW Choma 9211627961 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 7 B 32 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 32 Saravan kumar Patwari SEC -14 -Huda 8901480431 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 8 B 33 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 33 Vineet Kumar JBT GPS Sarai Alawardi 9991284502 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 9 B 34 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 34 Roshni AWW Sarai Alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 10 B 36 1 Sh. -

Risk Assessment & Hazard Management

Expansion cum modification of IT park at Village - Ghatta, Sector -61, Gurugram, Haryana M/s Active Promoters Pvt. Ltd. & Others. Report of Functional Area Expert For “Risk Assessment & Hazard Management” (RH) Prepared and submitted by FAE- Mrs. Anuradha Sharma Study Period: Nov,2017 – Jan, 2018 Prepared by : Anuradha Sharma FAE-RH Cat “A” Page 1 Expansion cum modification of IT park at Village - Ghatta, Sector -61, Gurugram, Haryana M/s Active Promoters Pvt. Ltd. & Others. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Project Proponent: M/S Active Promoters Pvt Ltd & Others 1.1 Name of the Project: Expansion Cum Modification of IT Park 1.2 Location: At Village- Ghatta, Sector-61, Gurugram, Haryana 1.3 Project Category as per EIA Notification: 8 (b) Cat “b” 2.0 Project Identification Table 1.1: Project Description S. No. Items Details Name of the Project Expansion cum modification of IT Park by M/s Active 1 Promoters Pvt. Ltd. & Others. Serial No. in schedule 8(b) “Building & Construction Projects” as per MoEF 2 notification 14/9/2006 Proposed capacity/area/length/tonnage to Total area = 50,342.94 m2 be handled/command area/lease Total Built-up area = 2,48,179.10 m2 area/number of wells to be drilled 2 3 Permissible Ground Coverage @ 40% : 21,345.1 m Proposed Ground Coverage @35.50%: 15,308.66 m2 Permissible FAR: 1,47,620.32 m2 Achieved FAR : 1,46,944.40 m2 4 New/Expansion/Modernization Modification cum Expansion 5 Existing capacity/area etc. Existing Built up area- 2,13,417.52 m2 6 Category of project B 7 Does it attract the general condition? If No Yes, please specify 8 Does it attract the specific condition? If No Yes, please specify 9 i) Location of unit Village – Ghatta, Sector-61, Gurugram, Haryana ii) Khasra No. -

District Disaster Management Plan GURGAON 2012

District Disaster Management Plan GURGAON 2012 P.C.Meena, IAS Deputy Commissioner-cum-Chairperson, District Disaster Management Authority Gurgaon Contents 1. Gurgaon District Profile 1-13 2. Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Analysis 14-22 3. Mitigation and Preparedness 23-30 4. Institutional and Legal Arrangements 31-40 5. Emergency Operation Centre 41-50 6. Response Plan 51-84 7. Resource Inventory 85-153 8. Annexure 154-171 ii- CHAPTER 1 GURGAON DISTRICT PROFILE 1. Introduction The primary requirement for making disaster management plan is the reliable and upto date information about topography and socio- economic and climatic conditions of this region. This will help in identifying the areas vulnerable to environmental and manmade hazards. This chapter deals with the information on geographical aspects of Gurgaon district, its area, population distribution, climatic condition, physiographic divisions as well as geology of the district. History of problem prone activities in Gurgaon has also been mentioned to depict the picture, as to how, the district is prone to different kinds of hazards like earthquakes, flood, serial bomb blasts, industrial disasters, fire etc. Information on Socio-economic programmes e.g. literacy rate, education facility and public welfare schemes of the district are also mentioned here to show the central stage that Gurgaon has already occupied in the state called Haryana – one of the most vibrant states of India. 1.1 The Need for district disaster management plan: Gurgaon is the sixth largest city of Haryana State. For the last two decades, it has been on the faster pace of the development. And emerged as the industrial and financial hub of Haryana. -

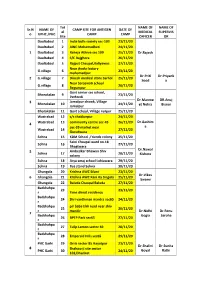

Sr.N O NAME of UPHC /PHC Tot Al Site CAMP SITE for ANTIGEN

Tot NAME OF NAME OF Sr.N NAME OF CAMP SITE FOR ANTIGEN DATE OF al MEDICAL SUPERVIS o UPHC /PHC CAMP CAMP Site OFFICER OR Daultabad 1 India bulls society sec-103 23/11/20 Daultabad 2 AWC Mohamadheri 24/11/20 1 Daultabad 3 Raheja Athrva seC 109 25/11/20 Dr.Rajesh Daultabad 4 S/C Bajghera 26/11/20 Daultabad 5 Rajput Chaupal,Kaliyawas 27/11/20 Near jhadu faCtory G.village 6 23/11/20 mohomadpur Dr.Priti Dr.Priyank 2 G.village 7 Dinesh mediCal store Sarhol 25/11/20 Sood a Near Saraswati sChool G.village 8 26/11/20 Begumpur Govt senior seC sChool, Bhorakalan 9 23/11/20 Pathredi Dr.Manme DR.Anuj 3 Jamalpur choWk, Village Bhorakalan 10 24/11/20 et Nehra Bisnoi Jamalpur Bhorakalan 11 Govt sChool, Village nurpur 25/11/20 Wazirabad 12 s/c chakkarpur 24/11/20 Dr.Aashim 4 Wazirabad 13 community centre sec-45 26/11/20 sec-39 market near a Wazirabad 14 27/11/20 Gurudwara Sohna 15 KDM School ,Friends Colony 25/11/20 Saini Chaupal Ward no.18 Sohna 16 27/11/20 Bhagtwara Dr.Nawal 5 Ambedkar Bhawan Shiv Sohna 17 28/11/20 Kishore colony Sohna 18 Arya smaj school LohiaWara 29/11/20 Sohna 19 Bus stand Sohna 30/11/20 Ghangola 20 Krishna AWC Silani 23/11/20 Dr.Vikas 6 Ghangola 21 Krishna AWC Rani Ka Singola 25/11/20 Swami Ghangola 22 Baluda Chaupal Baluda 27/11/20 Badshahpu 23 23/11/20 r Time dhoot residenCy Badshahpu 24 Shri vardhman mantra seC65 24/11/20 r Badshahpu pir baba tikli road near shiv 25 26/11/20 r mandir Dr.Nidhi Dr.Renu 7 Badshahpu Gogia Saroha 26 BPTP Park seC65 27/11/20 r Badshahpu 27 Tulip Lemon sector 69 28/11/20 r Badshahpu 28 Emperald Hills -

Circle Rates

g.r.p....) Year 2oL8-2or9 w.e.f. -Q-T:Q. Year of 2OL7-2OL8 Rates for the Year of 2OL8-2OL9 Rates for the year 2OL6-2OL7 Rates for the Rates of Land upto 2 Acre depth from NH-48, l\lDD lirraroam-(ahare .rveeAazA 1\oAl Mainr .rt rr, vur u6. -"vt '!!erv. District Road 10% Residentiol Commercial Agriculture Residentiol Commercial Sr. Name of Village Agriculture Residentiol Commercidl Agriculture Major District Road / Land (Rs. Per (Rs. Per Sq. Rs. Per Sq. NH-48, NPR, Gurugram No. Land (Rs. Per (Rs. Per Sq. Land (Rs. Per (Rs" Per 5q. State Highway Sohna Road Acre) Yards.) Acre) Yards.) Acrel Yards.) Yards.l 14800 3130C 18139000 27000 4200c 25% NPR 22673750 NA NA 1 Gurgaon Village 1870000c 15300 32300 18139000 2040000c 15300 32300 20400000 15300 3230C 2 lnayatpur 20400000 17000 4200c NA NA NA NA na na na 17000 42000 NA NA NA NA 3 Hidavatpur Chawani na na na na 31300 4 Sarhaul 22950000 15300 3230C 2226L500 14800 2226150C 18000 44000 25% NH-48 27826875 10% STHW 24487650 18100 3460C 5 Dundahera 22950000 18700 3570C 22261500 2226L50C 19800 4r'}OOO 25% NH-48 27826875 10% STHW 24487650 212nn 6 Moalhera 22950000 15300 32300 2226L504 14900 2226L50C i7000 4ZUUU NA NA NA NA 26400 7 Nathupur 22950000 14450 27200 2226150C 14100 2226L50C 4500c 60000 NA NA NA NA 36700 8 Sikanderpur Ghosi 20400000 15300 37400 1999200C 15000 19992000 s000c 78000 NA NA NA NA 1500c 3170C 9 Shahpur 2295000C 15300 32300 2249LOOC 2249LOOO 1800c 44000 25% NH-48 28LL3750 NA NA t796C 10 Bajghera 16150000 8s0c 18700C 15504000 820C 15504000 1500c 3s000 NA NA NA NA 12200 22000 11 SaraiAlawardi -

DBA-VOTING-LIST-2018.Pdf

Sl.No. Name Address Bar Council Bar No. Phone Phone T.U.P. H.No-322/14, Jacubpura, 1 A.L.Sahni P/1007/1983 2 2321473 9313401837 Gurgaon H.No-763-A, Ist Floor, 2 Aakash Aggarwal Block-H, Palam Vihar, P/695/1999 4 9350840785 9910991353 Gurgaon. V.P.O. Dhunela, Post 3 Aakil Ali P/3239/2014 4051 9050300395 9813313823 Office Sohna, Gurgaon H.No-249,Sector-17-A 4 Aarti Bhalla P/2016/2015 4246 9350320004 Gurgaon. H.No-224/7, H.B. 5 Aarti Hans Colony, Sec-7 Ext, P/1398/2011 3061 9910383914 Gurgaon Vill- Udaka, PO-Sohna, 6 Aazad P/3601/2009 2544 9711115701 Distt- Gurgaon Gandhi Nagar Ward No. 7 Abdul Hamid 8 Opp Mewat Model P/778/1994 4054 8860481185 School Tauru. Vill-Rewasan, Teh -Nuh, 8 Abdul Rehman P/95/1998 6 9416256151 9813039030 Distt-Gurgaon PWO Housing Complex, B-2/301, Sector 43, 9 Abha Sinha Sushant Lok-I, Gurgaon P/1800/1999 4751 9871957449 At(P) C-6/6360, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi H.No-645/20, Gali No-6, 10 Abhai singh Yadav P/514/1977 3100 9250171144 Shivji Park, Gurgaon Abhey singh H.No.1434, Sec-15, Part- 0124- 11 P/1132/2001 8 9811198319 Dahima II, Gurgaon. 6568432 Resi-Vill-Dhanwa Pur, Abhey Singh 12 Po-Daulta Bad, Distt- P/857/1995 9 9811934070 Dahiya Gurgaon H.No-209/4, Subhash 13 Abhey Singla P/420/2007 2008 9999499932 9811779952 Nagar, Gur. H.No. 225, sector 15, 14 Abhijeet Gupta P/4107/2016 4757 9654010101 Part-I, Gurgaon. -

Rupesh Kumar Gupta Sudesh Nangia

Population Explosion and Land Use Changes in Gurgaon City Region-A Satellite of Delhi Metropolis Rupesh Kumar Gupta Sudesh Nangia, Key Words: L and transformation, Urban encroachment, Built-up land, Multi-Temporal, Spatio-Tempo., RS, GIS Abstract In developing countries, rapid population growth has meant a decline in the arable land per capita and switch over to industrial, residential, commercial land uses. In 1961, for example, developing countries as a whole had an average of about one-half of a hectare of arable land per person; by 1992 the share had fallen to less than one-fifth of an hectare. If current trends in population growth continue, it is estimated that by 2050,the amount of arable land will be just over one-tenth hectare per person. This paper is the case study of a town named Gurgaon in the urban shadow zone of capital city of India i.e. Delhi, in terms of its population explosion and land use changes. The population of Gurgaon has grown from 57 thousand in 1971 to 1.74 lakh in 2001. The growth rate has also indicated an increasing trend. In addition, the pressure of continuously growing metropolitan city is also changing the structure of the town and its surrounding neighborhood. In this paper, the authors have tried to investigate the changes in land use pattern of Gurgaon region that have occurred over the past few decades, and have tried to associate them with population growth, urbanization and industrialization of the countryside. For this purpose, multi-temporal RS and GIS data sets are used. -

HEALTH DEPARTMENT Gurugram Integrated Disease Surveillance Program Email :- [email protected] Media Bulletin on COVID-19 Dated 09-06-2020

HEALTH DEPARTMENT Gurugram Integrated Disease Surveillance Program Email :- [email protected] Media Bulletin on COVID-19 dated 09-06-2020 World health organization (WHO) has recently declared the Novel Corona Virus COVID-19 as pandemic. In Order to contain the spread of the virus, Haryana Govt. has strengthened the surveillance and control measures against the diseases. The detailed status of surveillance activity for COVID-19. Cumulative No. of Passengers/Persons put on surveillance till date 23650 Cumulative No. of Passengers/Persons who have completed surveillance period of 14 days 18600 New Case Reported Today 164 01 Case Linked with 4 Marla , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with 8 Marla, Gurugram 03 Case Linked with Adarsh Nagar , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Alipur , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Arjun Nagar , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Ashok Vihar , Gurugram 02 Case Linked with Basai village, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Bhim Nagar , Gurugram 03 Case Linked with Bhondsi, Gurugram 04 Case Linked with Budhera, Gurugram 02 Case Linked with Chakkarpur , Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Village- Chakkarpur, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Dhanwapur, Gurugram 164 03 Case Linked with DLF Phase 1 , Gurugram 03 Case Linked with DLF Phase 2 , Gurugram 02 Case Linked with DLF Phase 3, Gurugram 02 Case Linked with DLF Phase 4, Gurugram 04 Case Linked with DLF Phase 5, Gurugram 02 Case Linked with Farrukh Nagar, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Fazilpur Dhani, Gurugram 04 Case Linked with Gandhi Nagar, Gurugram 01 Case Linked with Gari Harsaru, Gurugram -

Health Care Facilities in Gurgaon and Improvement Ideas

HEALTH CARE FACILITIES IN GURGAON AND IMPROVEMENT IDEAS BACKGROUND OF GURGAON : The district has been in existence since the times of Mahabharata and was named as Guru-gram, which in course of time changed to Gurgaon. Gurgaon is a leading financial and industrial center, situated in the National Capital Region near the Indian capital New Delhi in the state of Haryana. Located 19.9 miles (32 km) south-west of New Delhi, Gurgaon has a population of 1,876,824. Witnessing rapid urbanization, Gurgaon has become the city with the third highest per capita income in India. INTRODUCTION : This document is intended to highlight the health care facilities (both public and private) available in Gurgaon, to share opinions of eminent citizens of Gurgaon and to share improvement ideas of the existing system. HEALTH CARE FACILITIES IN GURGAON : In public health care Gurgaon has total 3 general hospitals, 12 community/public healthcare centers (CHC/PHC’s), 1 special protection group’s hospital and 4 ESI dispensaries. All this combined have total 378 Nos. beds. Whereas Gurgaon has total 99 Nos. of private hospitals, trust hospitals & nursing homes with total beds capacity of 2451 Nos. (see Annexure 1 for list of public and private hospitals with their individual bed capacity). There are total 9 Nos. of public and 87 Nos. of private/trust/nursing home ambulances in Gurgaon (see Annexure 2 for list of ambulances and contact information). Gurgaon also has 1 No. of public and 8 Nos. private/trust blood banks (see Annexure 3 for list of blood banks and their contact information). -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Subaltern counter-urbanism dynamics of urban and industrial change in Gurgaon, India’s millennium city Cowan, Thomas Grant Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 1 Subaltern counter-urbanism: dynamics of urban and industrial change in Gurgaon, India’s millennium city Thomas Cowan PhD, Geography (Arts) Department of Geography Words: 96771 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... -

D.No.5-3-682,Shop No.4,Vijayapuri Colony Phase-1,Vana

S.NO City STORE NAME ADDRESS VIJAYAPURI 1 Hyderabad COLONY(VANASTALIPURAM) D.No.5-3-682,Shop No.4,Vijayapuri Colony Phase-1,Vanasthalipuram,Ranga Reddy Dist-500070 D.No.5-5-148/4 &5-5-148/5,Beside Heritage Supermarket,Vanasthali Hills,Saheb Nagar,Ranga 2 Hyderabad VANASTHALI HILLS Reddy (DT)500070 . 3 Hyderabad VANASTHALIPURAM DR NO-6-2-688,PHASE2 LIG VANASTHALIPURAM SAHEB NAGAR KALAN RR DISTS 500070 4 Hyderabad B.N.REDDY-VANASTHALIPURAM H.No.Type-II-30, Shop No.1&2, Self Finance Colony, Vanasthalipuram, Hyderabad-70. GANESH TEMPLE- 5 Hyderabad VANASTHALIPURAM D.No: 6-2-689,Near: Ganesh Temple Road, Phase -II, Vanasthalipuram, Haythnagar(m) R.R.Dist 6 ROAP MAHABOOBNAGAR 1-5-35/6, New Town, Mahaboob Nagar, Mahaboob Nagar Dist. METTUGUDA - 7 ROAP MAHABOOBANAGAR - 2 H.No.1-4-30/D/B, Mettuguda, Opp.Govt.Hospitals, Mahaboobnagar. 8 ROAP KALWAKURTHY 6-20/4, Opp SBI Kalwakurthy, Mahaboob Nagar 9 ROAP ACHAMPET H-NO:4-186,MAIN ROAD, NEAR POST OFFICE, ACHAMPET, MAHABOOBNAGAR DIST. 509375. 10 ROAP JADCHERLA D.No.16-4,Netaji Road,Badepally (Village), Jadcherla(MA),Mahabub Nagar Dist-509304 NARAYANAPET D.No.1-6-86, Main Road, Near Old Busstand, Narayanpet (Post & Mandal), Mahaboob Nagar Dist 11 ROAP (MAHABOOBNAGAR) - 509210 VENKATESHWARA COLONY 12 ROAP (MAHABUB NAGAR ) D.No.7-4-58/A,Venkateshwar Colony,Main Road Opp:A.P.S.E.B.Buliding,Mahabub D NO : 2-99,PADMAVATHI COLONY, SHADNAGAR, FAROOQ NAGAR, 13 ROAP SHADNAGAR MAHABOOBNAGAR,TELANGANA, AP 14 ROAP KOTHUR D.NO.1-46,PENJARLA ROAD, OPP .S.B.H, KOTHUR, MAHBOOB NAGAR DIST-509338(AP) 15 ROAP CLOCK TOWER,MBNR D-NO.2-6-94/2,MARKET ROAD, CLOCK TOWER, MAHABUB NAGAR 16 ROAP NEW TOWN,MBNR D.No.1-5-69/1B, NEW TOWN, MAHABOOB NAGAR DIST VENKATESWARACOLONY, 17 ROAP MBNR H.No.7-5-108 & 7-5-109, Venkateswara Colony, Mahaboob Nagar . -

List of Colonies in Villages

Circle rates – Gurgaon from April 1, 2010 onwards LIST OF COLONIES IN VILLAGES Name Year 2010-2011 Residential Commercial 1. Babupur 3500 9000 2. Badshahpur 4800 12000 3. Bajghera 3500 9000 4. Basai 5500 12000 5. Chakkarpur 6500 17000 6. Chauma 4000 9000 7. Dhanwapur 3500 9000 8. Dundahera 6500 18000 9. Garhi Harsaru 2400 9000 10. Gurgaon Village 6500 22000 11. Islampur 6000 13000 12. Jharsa Village 6500 15000 13. Kanhai 6500 15000 14. Kadipur 6000 13000 15. Khandsa 6000 16000 16. Karterpuri 6500 13000 17. Narsing Pur 6000 16000 18. Nathupur 6500 17000 19. Naharpur Roopa 6000 17000 20. Molahera 6500 17000 21. Pawala Khusrupur 3500 11000 22. Sarhaul 6500 16000 23. Samaspur 6500 15000 24. Tikri 4500 9500 25. Tigra 6000 11000 26. Virendra Gram 5500 8500 As is information. Shared as received. You may recheck with competent authority before conducting the transaction. We will not be responsible for the correctness of the content 27. Wazirabad 6500 15000 REVISED RATES FOR AGRICULTURE LAND & PLOT FOR YEAR 2010-11 Name Year 2010-2011 All Type of Land Gair Mumkin Plot 1. Aklimpur 3500000 1900 2. Adampur 12000000 6500 3. Sarai Alwardi 6000000 5500 4. Bindapur 12000000 6500 5. Bashariya 6000000 3500 6. Banskusla 6000000 3500 7. Begampur Khatola 8000000 4000 8. Badshahpur 8000000 4800 9. Behrampur 8000000 3500 10. Bajghera 6700000 ------ 11. Babupur 6700000 ------ 12. Budhera 3000000 1900 13. Basai 6700000 ------ 14. Bamrouli 6700000 3500 15. Bhangroula 6700000 3500 16. Chakkarpur 12000000 ------ 17. Chauma 7800000 ------ 18. Chandu 3000000 1700 19. Dhorka 6700000 3000 20. Dhana 6700000 3500 21.