Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Ward Wise List of Sector Officers, Blos & Blo Supervisors, Municipal

WARD WISE LIST OF SECTOR OFFICERS, BLOS & BLO SUPERVISORS, MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, GURUGRAM Sr. Constit Old P S Ward Sector Officer Mobile No. New Name of B L O Post of B L O Office Address of B L O Mobile No Supervisior Address Mobile No. No. uenc No No. P S No 1 B 15 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 15 Nirmala AWW Pawala Khushrupur 9654643302 Joginder Lect. HIndi GSSS Daultabad 9911861041 (Jahajgarh) 2 B 26 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 26 Roshni AWW Sarai alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 3 B 28 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 28 Anand AWW Choma 9582167811 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 4 B 29 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 29 Rakesh Supervisor XEN Horti. HSVP Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 5 B 30 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 30 Pooja AWW Sarai alawardi 9899040565 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 6 B 31 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 31 Santosh AWW Choma 9211627961 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 7 B 32 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 32 Saravan kumar Patwari SEC -14 -Huda 8901480431 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 8 B 33 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 33 Vineet Kumar JBT GPS Sarai Alawardi 9991284502 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 9 B 34 1 Sh. Raj Kumar JE 7015631924 34 Roshni AWW Sarai Alawardi 9718414718 Pyare Lal Kataria Lect. Pol. GSSS Bajghera 9910853699 10 B 36 1 Sh. -

21St Camp Site

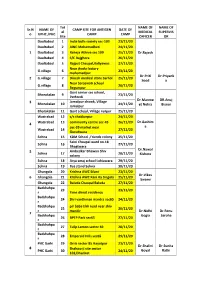

21st Antigen Camp Site w.e.f - 16-12-2020 To 22-12-2020 NAME OF UPHC NAME OF MEDICAL NAME OF Sr.No Total Site Sr.No. CAMP SITE FOR ANTIGEN CAMP DATE OF CAMP /PHC OFFICER SUPERVISOR 1 1 Village Joniawas 16/12/20 2 2 GPS Khurumpur 18/12/20 1 Farrukhnagar Dr. Kanika 3 3 CHC Farrukhnagar 20/12/20 4 4 SuB Center Patli 22/12/20 5 1 PHC Bhangrola 16/12/20 6 2 Wazirpur Jhuggies 17/12/20 7 3 Bestech Park View Sec.92 18/12/20 2 Bhangrola 8 4 G21, Sec. 83 19/12/20 Dr. Shalu 9 5 SuB Centre Kakrola 20/12/20 10 6 Coralwood Sec.84 21/12/20 11 7 Near Shiv Mandir Village Jadola 22/12/20 12 1 AWC Mehniyawas 16/12/20 13 2 AWC Ghilawas 17/12/20 3 Mandpura Dr. Vipin 14 3 AWC Khetiyawas 18/12/20 15 4 AWC Faridpur 19/12/20 16 1 AmBedkar Bhawan , Shiv Colony 16/12/20 17 2 Arya Samaj School , Lohiyawada 20/12/20 4 Sohna Dr. Navel Kisor 18 3 Bus Stand Sohna 21/12/20 19 4 Anaj Mandi Sohna 22/12/20 20 1 Golden Greens Golf CluB , Village Sakatpur 16/12/20 21 2 Tripti Jhuggies Sec.70A 17/12/20 Dr. Sandeep Gupta 5 Palra 22 3 Peace Shelter Homes Society Sec. 70A 18/12/20 23 4 Lohagarh Farm House 19/12/20 24 5 M3M Escala Society Sec. 70A 21/12/20 25 1 NBCC Heights Sec. -

Risk Assessment & Hazard Management

Expansion cum modification of IT park at Village - Ghatta, Sector -61, Gurugram, Haryana M/s Active Promoters Pvt. Ltd. & Others. Report of Functional Area Expert For “Risk Assessment & Hazard Management” (RH) Prepared and submitted by FAE- Mrs. Anuradha Sharma Study Period: Nov,2017 – Jan, 2018 Prepared by : Anuradha Sharma FAE-RH Cat “A” Page 1 Expansion cum modification of IT park at Village - Ghatta, Sector -61, Gurugram, Haryana M/s Active Promoters Pvt. Ltd. & Others. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Project Proponent: M/S Active Promoters Pvt Ltd & Others 1.1 Name of the Project: Expansion Cum Modification of IT Park 1.2 Location: At Village- Ghatta, Sector-61, Gurugram, Haryana 1.3 Project Category as per EIA Notification: 8 (b) Cat “b” 2.0 Project Identification Table 1.1: Project Description S. No. Items Details Name of the Project Expansion cum modification of IT Park by M/s Active 1 Promoters Pvt. Ltd. & Others. Serial No. in schedule 8(b) “Building & Construction Projects” as per MoEF 2 notification 14/9/2006 Proposed capacity/area/length/tonnage to Total area = 50,342.94 m2 be handled/command area/lease Total Built-up area = 2,48,179.10 m2 area/number of wells to be drilled 2 3 Permissible Ground Coverage @ 40% : 21,345.1 m Proposed Ground Coverage @35.50%: 15,308.66 m2 Permissible FAR: 1,47,620.32 m2 Achieved FAR : 1,46,944.40 m2 4 New/Expansion/Modernization Modification cum Expansion 5 Existing capacity/area etc. Existing Built up area- 2,13,417.52 m2 6 Category of project B 7 Does it attract the general condition? If No Yes, please specify 8 Does it attract the specific condition? If No Yes, please specify 9 i) Location of unit Village – Ghatta, Sector-61, Gurugram, Haryana ii) Khasra No. -

District Disaster Management Plan GURGAON 2012

District Disaster Management Plan GURGAON 2012 P.C.Meena, IAS Deputy Commissioner-cum-Chairperson, District Disaster Management Authority Gurgaon Contents 1. Gurgaon District Profile 1-13 2. Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Analysis 14-22 3. Mitigation and Preparedness 23-30 4. Institutional and Legal Arrangements 31-40 5. Emergency Operation Centre 41-50 6. Response Plan 51-84 7. Resource Inventory 85-153 8. Annexure 154-171 ii- CHAPTER 1 GURGAON DISTRICT PROFILE 1. Introduction The primary requirement for making disaster management plan is the reliable and upto date information about topography and socio- economic and climatic conditions of this region. This will help in identifying the areas vulnerable to environmental and manmade hazards. This chapter deals with the information on geographical aspects of Gurgaon district, its area, population distribution, climatic condition, physiographic divisions as well as geology of the district. History of problem prone activities in Gurgaon has also been mentioned to depict the picture, as to how, the district is prone to different kinds of hazards like earthquakes, flood, serial bomb blasts, industrial disasters, fire etc. Information on Socio-economic programmes e.g. literacy rate, education facility and public welfare schemes of the district are also mentioned here to show the central stage that Gurgaon has already occupied in the state called Haryana – one of the most vibrant states of India. 1.1 The Need for district disaster management plan: Gurgaon is the sixth largest city of Haryana State. For the last two decades, it has been on the faster pace of the development. And emerged as the industrial and financial hub of Haryana. -

Sr.N O NAME of UPHC /PHC Tot Al Site CAMP SITE for ANTIGEN

Tot NAME OF NAME OF Sr.N NAME OF CAMP SITE FOR ANTIGEN DATE OF al MEDICAL SUPERVIS o UPHC /PHC CAMP CAMP Site OFFICER OR Daultabad 1 India bulls society sec-103 23/11/20 Daultabad 2 AWC Mohamadheri 24/11/20 1 Daultabad 3 Raheja Athrva seC 109 25/11/20 Dr.Rajesh Daultabad 4 S/C Bajghera 26/11/20 Daultabad 5 Rajput Chaupal,Kaliyawas 27/11/20 Near jhadu faCtory G.village 6 23/11/20 mohomadpur Dr.Priti Dr.Priyank 2 G.village 7 Dinesh mediCal store Sarhol 25/11/20 Sood a Near Saraswati sChool G.village 8 26/11/20 Begumpur Govt senior seC sChool, Bhorakalan 9 23/11/20 Pathredi Dr.Manme DR.Anuj 3 Jamalpur choWk, Village Bhorakalan 10 24/11/20 et Nehra Bisnoi Jamalpur Bhorakalan 11 Govt sChool, Village nurpur 25/11/20 Wazirabad 12 s/c chakkarpur 24/11/20 Dr.Aashim 4 Wazirabad 13 community centre sec-45 26/11/20 sec-39 market near a Wazirabad 14 27/11/20 Gurudwara Sohna 15 KDM School ,Friends Colony 25/11/20 Saini Chaupal Ward no.18 Sohna 16 27/11/20 Bhagtwara Dr.Nawal 5 Ambedkar Bhawan Shiv Sohna 17 28/11/20 Kishore colony Sohna 18 Arya smaj school LohiaWara 29/11/20 Sohna 19 Bus stand Sohna 30/11/20 Ghangola 20 Krishna AWC Silani 23/11/20 Dr.Vikas 6 Ghangola 21 Krishna AWC Rani Ka Singola 25/11/20 Swami Ghangola 22 Baluda Chaupal Baluda 27/11/20 Badshahpu 23 23/11/20 r Time dhoot residenCy Badshahpu 24 Shri vardhman mantra seC65 24/11/20 r Badshahpu pir baba tikli road near shiv 25 26/11/20 r mandir Dr.Nidhi Dr.Renu 7 Badshahpu Gogia Saroha 26 BPTP Park seC65 27/11/20 r Badshahpu 27 Tulip Lemon sector 69 28/11/20 r Badshahpu 28 Emperald Hills -

112A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

112A bus time schedule & line map 112A Chandan Vihar (New Palam Vihar-II) - Haryana View In Website Mode Vidyut Prasaran Nigam The 112A bus line (Chandan Vihar (New Palam Vihar-II) - Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandan Vihar (New Palam Vihar-Ii): 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM (2) Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam: 8:05 AM - 9:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 112A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 112A bus arriving. Direction: Chandan Vihar (New Palam Vihar-Ii) 112A bus Time Schedule 36 stops Chandan Vihar (New Palam Vihar-Ii) Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam (H.V.P.N.) Monday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Sector 55 / 56 Metro Station Tuesday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Sector 55 / 56 Wednesday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Thursday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Sector 54 Chowk Metro Station Friday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Vatika Tower / Saraswati Kunj Saturday 7:00 AM - 8:25 PM Vatika Business Centre Sector 53 / 54 Metro Station 112A bus Info Genpact Chowk Direction: Chandan Vihar (New Palam Vihar-Ii) Stops: 36 Sector 42 / 43 Metro Station Trip Duration: 54 min Golf Course Road, Gurugram Line Summary: Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam (H.V.P.N.), Sector 55 / 56 Metro Station, Sector 55 / Phase-I Metro Station 56, Sector 54 Chowk Metro Station, Vatika Tower / Saraswati Kunj, Vatika Business Centre, Sector 53 / Sikanderpur Metro Station 54 Metro Station, Genpact Chowk, Sector 42 / 43 Metro Station, Phase-I Metro Station, Sikanderpur Guru Dronacharya Metro -

Circle Rates

g.r.p....) Year 2oL8-2or9 w.e.f. -Q-T:Q. Year of 2OL7-2OL8 Rates for the Year of 2OL8-2OL9 Rates for the year 2OL6-2OL7 Rates for the Rates of Land upto 2 Acre depth from NH-48, l\lDD lirraroam-(ahare .rveeAazA 1\oAl Mainr .rt rr, vur u6. -"vt '!!erv. District Road 10% Residentiol Commercial Agriculture Residentiol Commercial Sr. Name of Village Agriculture Residentiol Commercidl Agriculture Major District Road / Land (Rs. Per (Rs. Per Sq. Rs. Per Sq. NH-48, NPR, Gurugram No. Land (Rs. Per (Rs. Per Sq. Land (Rs. Per (Rs" Per 5q. State Highway Sohna Road Acre) Yards.) Acre) Yards.) Acrel Yards.) Yards.l 14800 3130C 18139000 27000 4200c 25% NPR 22673750 NA NA 1 Gurgaon Village 1870000c 15300 32300 18139000 2040000c 15300 32300 20400000 15300 3230C 2 lnayatpur 20400000 17000 4200c NA NA NA NA na na na 17000 42000 NA NA NA NA 3 Hidavatpur Chawani na na na na 31300 4 Sarhaul 22950000 15300 3230C 2226L500 14800 2226150C 18000 44000 25% NH-48 27826875 10% STHW 24487650 18100 3460C 5 Dundahera 22950000 18700 3570C 22261500 2226L50C 19800 4r'}OOO 25% NH-48 27826875 10% STHW 24487650 212nn 6 Moalhera 22950000 15300 32300 2226L504 14900 2226L50C i7000 4ZUUU NA NA NA NA 26400 7 Nathupur 22950000 14450 27200 2226150C 14100 2226L50C 4500c 60000 NA NA NA NA 36700 8 Sikanderpur Ghosi 20400000 15300 37400 1999200C 15000 19992000 s000c 78000 NA NA NA NA 1500c 3170C 9 Shahpur 2295000C 15300 32300 2249LOOC 2249LOOO 1800c 44000 25% NH-48 28LL3750 NA NA t796C 10 Bajghera 16150000 8s0c 18700C 15504000 820C 15504000 1500c 3s000 NA NA NA NA 12200 22000 11 SaraiAlawardi -

DBA-VOTING-LIST-2018.Pdf

Sl.No. Name Address Bar Council Bar No. Phone Phone T.U.P. H.No-322/14, Jacubpura, 1 A.L.Sahni P/1007/1983 2 2321473 9313401837 Gurgaon H.No-763-A, Ist Floor, 2 Aakash Aggarwal Block-H, Palam Vihar, P/695/1999 4 9350840785 9910991353 Gurgaon. V.P.O. Dhunela, Post 3 Aakil Ali P/3239/2014 4051 9050300395 9813313823 Office Sohna, Gurgaon H.No-249,Sector-17-A 4 Aarti Bhalla P/2016/2015 4246 9350320004 Gurgaon. H.No-224/7, H.B. 5 Aarti Hans Colony, Sec-7 Ext, P/1398/2011 3061 9910383914 Gurgaon Vill- Udaka, PO-Sohna, 6 Aazad P/3601/2009 2544 9711115701 Distt- Gurgaon Gandhi Nagar Ward No. 7 Abdul Hamid 8 Opp Mewat Model P/778/1994 4054 8860481185 School Tauru. Vill-Rewasan, Teh -Nuh, 8 Abdul Rehman P/95/1998 6 9416256151 9813039030 Distt-Gurgaon PWO Housing Complex, B-2/301, Sector 43, 9 Abha Sinha Sushant Lok-I, Gurgaon P/1800/1999 4751 9871957449 At(P) C-6/6360, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi H.No-645/20, Gali No-6, 10 Abhai singh Yadav P/514/1977 3100 9250171144 Shivji Park, Gurgaon Abhey singh H.No.1434, Sec-15, Part- 0124- 11 P/1132/2001 8 9811198319 Dahima II, Gurgaon. 6568432 Resi-Vill-Dhanwa Pur, Abhey Singh 12 Po-Daulta Bad, Distt- P/857/1995 9 9811934070 Dahiya Gurgaon H.No-209/4, Subhash 13 Abhey Singla P/420/2007 2008 9999499932 9811779952 Nagar, Gur. H.No. 225, sector 15, 14 Abhijeet Gupta P/4107/2016 4757 9654010101 Part-I, Gurgaon. -

Rupesh Kumar Gupta Sudesh Nangia

Population Explosion and Land Use Changes in Gurgaon City Region-A Satellite of Delhi Metropolis Rupesh Kumar Gupta Sudesh Nangia, Key Words: L and transformation, Urban encroachment, Built-up land, Multi-Temporal, Spatio-Tempo., RS, GIS Abstract In developing countries, rapid population growth has meant a decline in the arable land per capita and switch over to industrial, residential, commercial land uses. In 1961, for example, developing countries as a whole had an average of about one-half of a hectare of arable land per person; by 1992 the share had fallen to less than one-fifth of an hectare. If current trends in population growth continue, it is estimated that by 2050,the amount of arable land will be just over one-tenth hectare per person. This paper is the case study of a town named Gurgaon in the urban shadow zone of capital city of India i.e. Delhi, in terms of its population explosion and land use changes. The population of Gurgaon has grown from 57 thousand in 1971 to 1.74 lakh in 2001. The growth rate has also indicated an increasing trend. In addition, the pressure of continuously growing metropolitan city is also changing the structure of the town and its surrounding neighborhood. In this paper, the authors have tried to investigate the changes in land use pattern of Gurgaon region that have occurred over the past few decades, and have tried to associate them with population growth, urbanization and industrialization of the countryside. For this purpose, multi-temporal RS and GIS data sets are used. -

Haryana State Council for Child Welfare 2010-11

HARYANA STATE COUNCIL FOR CHILD WELFARE 2010-11 Complete Postal Address of Crèche Units Friends Colony, Model Town, Ambala City 095518321 Prem Nagar, Near Gurudwara, A/City0171-2552425 Behind Bus Stop, Village Mallour 09896173951 Panchyat Dharamshalla, Vill. Jalbhera Panchyat Building, Vill. Mastpur 0171-2858910 Ram Nagar, A.City 09315859942 Moti Nagar, A/City09466506334 Kaith Majri, Near Sheesh Ganj Gurudwara Village Bhurangpur 0171-2857530 Baldev Nagar, A/City 09896439414 Creche Baldev Nagar, A/City 0171-2556537 ® Panchyat Dharamshalla, Near Gurudwara, Vill. Brara 09315666453 Panchyat Dharamshalla, Vill. Ugala 09896809586 Community Centre, Housing Board Colony, A/Cantt. 09729486678 Dina ki Mandi, Dharamshalla, Kumhar Mandi, A/Cantt. Community Centre, Village Mandhour.0171-2540124-R Dharamshalla, Village Sultanpur Barrier 0171-2542003 Public Library, Water Tanki, Mahesh Nagar, A/Cantt.09466596553 Dharamshalla, Near Govt. S.S. School, Vill. Babyal 0171-2663904 -R Bal Bhawan, A/City 0171-2556751 (B.B) Bal Bhawan, A/Cantt. 09466662477 Gujoani, Bhiwani Ward No. 10, Bhwani Khera, Bank Colony Bank Colony, Bhiwani M.C. Colony, Guwar Factory, Bhiwani Near Nand Trust Puccawala, Ward No. 4, Tosham, Bhiwani Near Sanatan Dharm MandirPanchyati Dharmshalla Tosham-II B.R.C.M School Kaunt Road, Bhiwani Bhootoka Mandir,Ward No. 2, Panchyati Dharmshall, Bhiwani Near Bal Udhyan Public School, Vidhya Nagar, Bhiwani Khatio Ki Dharmshall, Chang, Bhiwani Room No. 13, B.T.M Chowk, Labour Colony,, Bhiwani Near Oil Mill, Gali No. 4,Brijwasi Colony, Bhiwani # 25/50,Telewara, Bhiwani Jeetu Patit, Pawan School, Shanti Nagar, Bhiwani B.T.M Chowk, Room No. 14,Labour Colony, Bhiwani Balmiki Basti Dharmshalla, Ward No. 14, Dadri, Bhiwani Near B.T.M Mill, Main Gate, Bhiwani Indira Lane, T.I.T. -

Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem

Final Report Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem: An assessment of challenges and opportunities for adaptation in urban areas Report on completion of Project A joint study by The Energy & Resources Institute and India Water Partnership Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem © The Energy and Resources Institute 2015 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2015 Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. For more information Dr. Shresth Tayal Fellow & Area Convenor Water Resources Division T E R I Tel. 2468 2100 or 2468 2111 Darbari Seth Block E-mail [email protected] IHC Complex, Lodhi Road Fax 2468 2144 or 2468 2145 New Delhi – 110 003 Web www.teriin.org India India +91 • Delhi (0)11 ii Water Energy Food Nexus in Urban Ecosystem Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................. V LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1 1. WATER ENERGY FOOD NEXUS IN URBAN ECOSYSTEM ...................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................