Dun Struan Beag Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Download the .Pdf

Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll: Chapter 7 http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/rarfa/ironage Appendix 1: Excavated Forts, Duns and Brochs in Argyll (ordered by date of first excavation) Site Name Type NMRS No. Location First Other References Excavated Years Dun Mac Sniachan fort NM93NW 2 Lorn 1873 1874 Smith 1875 Dun Boraige Mor broch NL94NW 1 Tiree 1880 Piggot 1952 Dun Mor Vaul broch NM04NW 3 Tiree 1880 1962-4 MacKie 1974, 1997 Suidhe Chennaidh dun NN02SW 1 Lorn 1890 Christison 1891 Leccamore/South dun NM171SE 2 Lorn 1890 1892 MacNaughton; 1891, 1893 Dun an Fheurain dun NM82NW 9 Lorn 1895 1950, Anderson 1895a; Ritchie 1974 1963 Dun Nighean dun NL94SE 1 Tiree 1881 Sands 1882 Dun na Cleite dun NL93NE 5 Tiree 1881 Sands 1882 Ardifuir dun NR79NE 2 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905 Druim and Duin dun NR79SE 1 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905 Duntroon fort NR89NW 10 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905; Craw 1930; Lane and Campbell 2000 Dunadd fort NR89SW 1 Mid Argyll 1904 1905, Christison 1905 1929, Dunagoil fort NS056SE 4 Bute 1913 19801914-1 Mann 1915; Mann 1925; Harding 2004b 15, 1919, 1925 Section 7: The Iron Age Page 1 Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll: Chapter 7 http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/rarfa/ironage Site Name Type NMRS No. Location First Other References Excavated Years Dun Breac dun NR85NE 17 Kintyre 1914 Graham 1915 Clachan Ard dun NS05NW 3 Bute 1933 MacCallum; 1959, 1963 Eilean Buidhe dun NS07NW 4 Bute 1936 Maxwell 1941 Kildonan Bay dun NR72NE 5 Kintyre 1936 1937-38 Fairhurst 1939; Peltonberg -

Kintour Landscape Survey Report

DUN FHINN KILDALTON, ISLAY AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY DATA STRUCTURE REPORT May 2017 Roderick Regan Summary The survey of Dun Fhinn and its associated landscape has revealed a picture of an area extensively settled and utilised in the past dating from at least the Iron Age and very likely before. In the survey area we see settlements developing across the area from at least the 15 th century with a particular concentration of occupation on or near the terraces of the Kintour River. Without excavation or historical documentation dating these settlements is fraught with difficulty but the distinct differences between the structures at Ballore and Creagfinn likely reflect a chronological development between the pre-improvement and post-improvement settlements, the former perhaps a relatively rare well preserved survival. Ballore Kilmartin Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 [email protected] Scottish Charity SC022744 ii Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Archaeological and Historical Background 2 2.1 Cartographic Evidence of Settlement 4 2.2 Some Settlement History 6 2.3 A Brief History of Landholding on Islay 10 3. Dun Fhinn 12 4. Walkover Survey Results 23 5. Discussion 47 6. References 48 Appendix 1: Canmore Extracts 50 The Survey Team iii 1. Introduction This report collates the results of the survey of Dun Fhinn and a walkover survey of the surrounding landscape. The survey work was undertaken as part of the Ardtalla Landscape Project a collaborative project between Kilmartin Museum and Reading University, which forms part of the wider Islay Heritage Project. The survey area is situated on the Ardtalla Estate within Kildalton parish in the south east of Islay (Figure 1) and survey work was undertaken in early April 2017. -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

The Typological Study of the Structures of the Scottish Brochs Roger Martlew*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 112 (1982), 254-276 The typological study of the structures of the Scottish brochs Roger Martlew* SUMMARY brieA f revie f publishewo d work highlight varyine sth g qualit f informatioyo n available th n eo structural features of brochs, and suggests that the evidence is insufficient to support the current far- reaching theories of broch origins and evolution. The use of numerical data for classification is discussed, and a cluster analysis of broch dimensions is presented. The three groups suggested by this analysis are examined in relation to geographical location, and to duns and 'broch-like' structures in Argyll. While the method is concluded to be useful, an improve- qualit e mendate th th necessar s an f i i t y o improvyo t interpretationd ai resulte o et th d san . INTRODUCTION AND REVIEW OF PUBLISHED WORK The brochs of Scotland have attracted a considerable amount of attention over the years, from the antiquarians of the last century to archaeologists currently working on both rescue and research projects. Modern development principlee th n si techniqued san excavationf so , though, have been applie vero brochsdt w yfe . Severa excavatione th f o lpase decade w th fe tf o s s have indeed been more careful research-orientated projects tha indiscriminate nth e diggin lase th t f go century, when antiquarians seemed intent on clearing out the greatest number of brochs in the shortest possible time. The result, however, is that a considerable amount of material from brochs exists in museum collections, but much of it is from excavations carried out with slight regard for stratigraphy and is consequently of little use in answering the detailed questions set by modern hypotheses. -

Excavation of an Iron Age, Early Historic and Medieval Settlement and Metalworking Site at Eilean Olabhat, North Uist

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 138 (2008), 27–104 EXCAVATION AT EILEAN OLABHAT, NORTH UIST | 27 Excavation of an Iron Age, Early Historic and medieval settlement and metalworking site at Eilean Olabhat, North Uist Ian Armit*, Ewan Campbell† and Andrew Dunwell‡ with contributions from Rupert Housley, Fraser Hunter, Adam Jackson, Melanie Johnson, Dawn McLaren, Jennifer Miller, K R Murdoch, Jennifer Thoms, and Graeme Warren and illustrations by Alan Braby, Craig Evenden, Libby Mulqueeny and Leeanne Whitelaw ABSTRACT The promontory site of Eilean Olabhat, North Uist was excavated between 1986 and 1990 as part of the Loch Olabhat Research Project. It was shown to be a complex enclosed settlement and industrial site with several distinct episodes of occupation. The earliest remains comprise a small Iron Age building dating to the middle centuries of the first millennium BC , which was modified on several occasions prior to its abandonment. Much later, the Early Historic remains comprise a small cellular building, latterly used as a small workshop within which fine bronze and silverwork was produced in the fifth to seventh centuries AD . Evidence of this activity is represented by quantities of mould and crucible fragments as well as tuyère and other industrial waste products. The site subsequently fell into decay for a second time prior to its medieval reoccupation probably in the 14th to 16th centuries AD . Eilean Olabhat has produced a well-stratified, though discontinuous, structural and artefactual sequence from the mid-first millennium BC to the later second millennium AD , and has important implications for ceramic development in the Western Isles over that period, as well as providing significant evidence for the nature and social context of Early Historic metalworking. -

Section 1 Section 0

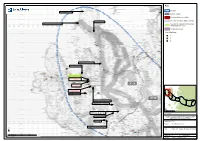

Key Corridor Dun Borrafiach Broch SM Section Divider Scheduled Monument (SM) Inventory of Historic Battlefields Site Dun Hallin Broch SM Trumpan Church and Burial Ground SM Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes Site (GDL) Conservation Area Listed Buildings ! A ! B ! C 0C - Greshornish 0A - Existing 0B - Garradh Mor Annait Monastic Settlement SM Dun Fiadhairt Broch SM Dunvegan Castle GDL Duirinish Parish Church A Listed Building Section 0 Dunvegan Castle A Listed Building Duirinish Parish Church A Listed Building Dun Osdale Broch SM 0E - Ben Aketil Section 1 St Mary's Church and Burial Ground Barpannan Chambered Cairns SM 0D - Existing ¯ 0 5 10 20 30 40 Kilometers Abhainn Bhaile Mheadhonaich Broch and Standing Stone SM Location Plan Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. Dun Feorlig, Broch SM Crown copyright and database right 2020 all rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number EL273236. Dun Neill SM Project No: LT91 Project: Skye Reinforcement Ardmore Chapel and Burial Ground SM ¯ Title: Figure 5.0 - Cultural Heritage (Section 0) 0 0.75 1.5 3 4.5 6 Kilometers Scale - 1:100,000 Drawn by: LT Date: 05/03/2020 Drawing: 119026-D-CH5.0-1.0.0 Key Corridor Section Divider Route Options Clach Ard Symbol Stone SM Scheduled Monument (SM) Skeabost Island, St Columba's Church SM Inventory of Historic Battlefields Site Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes Site (GDL) Conservation Area Listed Buildings ! A ! B ! C Section 0 Dun Arkaig Broch SM 1A - Existing Dun Garsin Broch SM Dun Mor Fort SM Dun Beag Broch SM Knock Ullinish Souterrain SM Section 1 Ullinish Lodge Chambered Cairn SM Ullinish Fort SM Dun Beag Cairn SM Struanmore Chambered Cairn SM 1B - A863 - Bracadale 1C - Tungadal - Sligachan Dun Ardtrack Galleried Dun SM ¯ 0 5 10 20 30 40 Kilometers Location Plan Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. -

Iron Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Images ©as noted in the text ScARF Summary Iron Age Panel Document September 2012 Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Summary Iron Age Panel Report Fraser Hunter & Martin Carruthers (editors) With panel member contributions from Derek Alexander, Dave Cowley, Julia Cussans, Mairi Davies, Andrew Dunwell, Martin Goldberg, Strat Halliday, and Tessa Poller For contributions, images, feedback, critical comment and participation at workshops: Ian Armit, Julie Bond, David Breeze, Lindsey Büster, Ewan Campbell, Graeme Cavers, Anne Clarke, David Clarke, Murray Cook, Gemma Cruickshanks, John Cruse, Steve Dockrill, Jane Downes, Noel Fojut, Simon Gilmour, Dawn Gooney, Mark Hall, Dennis Harding, John Lawson, Stephanie Leith, Euan MacKie, Rod McCullagh, Dawn McLaren, Ann MacSween, Roger Mercer, Paul Murtagh, Brendan O’Connor, Rachel Pope, Rachel Reader, Tanja Romankiewicz, Daniel Sahlen, Niall Sharples, Gary Stratton, Richard Tipping, and Val Turner ii Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Executive Summary Why research Iron Age Scotland? The Scottish Iron Age provides rich data of international quality to link into broader, European-wide research questions, such as that from wetlands and the well-preserved and deeply-stratified settlement sites of the Atlantic zone, from crannog sites and from burnt-down buildings. The nature of domestic architecture, the movement of people and resources, the spread of ideas and the impact of Rome are examples of topics that can be explored using Scottish evidence. The period is therefore important for understanding later prehistoric society, both in Scotland and across Europe. There is a long tradition of research on which to build, stretching back to antiquarian work, which represents a considerable archival resource. -

An Enhanced Object Biography of a Viking Age Or Late Norse Finger-Ring from the Isle of Jura in the Collection of Glasgow Museums

Proc Soc AntiqAN Scot ENHANCED 147 (2017), OBJECT 285–301 BIOGRAPHY OF A VIKING AGE OR LATE NORSE FINGER-RING | 285 DOI: https://doi.org/10.9750/PSAS.147.1230 Ossianic gold: an enhanced object biography of a Viking Age or Late Norse finger-ring from the Isle of Jura in the collection of Glasgow Museums Katinka Dalglish1 with James Graham-Campbell2 ABSTRACT A Viking Age or Late Norse gold finger-ring in Glasgow Museums (A.1979.19), previously thought to have been found in the Isle of Skye, is here identified with a ring said to have been found in the Isle of Jura in 1869 (together with another, now lost). This identification is based on an illustration published in 1875 by the ring’s then owner, the Rev Dr P H Waddell (1816–91). Waddell’s use of the ring as a piece of evidence in his attempts to prove the authenticity of James Macpherson’s Ossianic poems is discussed. The ring subsequently passed into the possession of the Austrian Countess Vincent Baillet de Latour (d 1942), who had developed an interest in the archaeology of Skye during her first marriage to Norman Macleod of Macleod (d 1895). Focusing on the ring as a collector’s possession, the paper takes a biographical approach, following its trajectory from antiquarian discovery to museum object. INTRODUCTION finger ring in recent times (Christie’s 1979: 12, lot 28). In 1979 Glasgow Museums acquired a gold The acquisition prompted Dr D W Phillipson, finger-ring at the Christie’s Fine Antiquities then Keeper of Archaeology, Ethnography sale held in London in November of that year and History at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and (Illus 1). -

Jarlshof Prehistoric and Norse Settlement

Property in Care no: 183 Designations: Scheduled Monument (90174) Taken into State care: 1925 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE JARLSHOF PREHISTORIC AND NORSE SETTLEMENT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH JARLSHOF PREHISTORIC AND NORSE SETTLEMENT BRIEF DESCRIPTION Jarlshof comprises a multi-period complex of well-preserved stone structures spanning from the late Neolithic (about 4500 years ago) to the 17th century AD. It was first discovered in 1897 and partly explored from 1897-1905. It was taken into guardianship in 1925, and further excavations accompanied by consolidation followed during the mid-1920s to late-1930s and from 1949- 52. The monument is located at the southern end of Shetland, overlooking the sheltered waters of the West Voe of Sumburgh and lying on good fertile land on the well drained lower slopes of the sandstone promontory of Sumburgh Head. Sir Walter Scott is responsible for the site’s romantic name. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview 2500-1500 BC – The earliest occupation consisted of the fragmentary walls and hearths of two buildings and an associated midden (rubbish dump) at NE end of site. 800 BC – The first village was established by 800 BC. The village, which included a Bronze-Age smithy, was located at the E end of site The Bronze- Age houses have distinct cells formed by thick buttresses extending into the living space, and are a type that can be traced back well before 2000 BC in Shetland. -

Broch of Gurness Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC277 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90157) Taken into State care: 1931 (Guardianship) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROCH OF GURNESS (AIKERNESS BROCH) We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROCH OF GURNESS (AIKERNESS