B24995290 Welch a I V2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metalwork & Woodwork Saws

HAMMERS - ANVILS - METALWORK & WOODWORK SAWS C HAMMERS BENCH PIN & ANVIL 77 CABLE TACKER GUN 76 DAVID USE PHOTO COPING SAWS 79 SD0010 FRETSAW BLADES 79 FRETSAW FRAMES 79 O HAMMER S & MALLETS 72 - 74 HACKSAWS 76 - 77 MINITURE ANVILS 74 MINITURE PINS 75 MALLET MITRE BOXES 82 PIERCING SAW BLADES 78 PIERCING SAW FRAMES 78 N DAVID USE PHOTO PIN PUSHERS 75 SD0010 RAZOR SAWS 81 SAW BLADE LUBRICANT 78 SAW KNIFE BLADES 81 STAPLE GUNS 75 - 76 V-BLOCK & CLAMPS 77 WEB STRETCHER 82 T ANVILS WOOD SAWS 80 - 81 X-ACTO RAZOR SAWS 81 DAVID USE PHOTO ZONA RAZOR SAWS 79 SD0010 E SAWS N DAVID USE PHOTO SD0010 T V BLOCK & CLAMP DAVID USE PHOTO SD0010 S Last Revised 04/07/2011 71 SQUIRES MODEL & CRAFT TOOLS HAMMERS & MALLETS MAGNETIC TACK HAMMER 6oz a specially designed hammer having one striking face magnetised for use when fitting small nails JEWELLERS MALLET a lightweight stainless steel mallet similar and upholstery tacks. The head features a claw for removing to those used by watchmakers and jewellers, with a solid head and tacks, the striking surface is a magnetic split pattern. The head is knurled shaft. hardened and pol- Length 145mm. ished. Fitted on a Weight 2½oz. hickory handle. Weight 6oz, length overall CODE TYPE PRICE 265mm. HA0025 Jewellers Mallet.................................................... £3.99 WATCHMAKERS MALLET a lightweight jewellers and watch- CODE TYPE PRICE makers mallet with a solid brass head. The handle is 260mm long 051-006 Magnetic Tack Hammer 6oz................................. £14.99 and has an increased diameter and is knurled for extra grip. -

Metals and Metal Products Tariff Schedules of the United States

251 SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS TARIFF SCHEDULES OF THE UNITED STATES SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS 252 Part 1 - Metal-Bearing Ores and Other Metal-Bearing Schedule 6 headnotes: Materials 1, This schedule does not cover — Part 2 Metals, Their Alloys, and Their Basic Shapes and Forms (II chemical elements (except thorium and uranium) and isotopes which are usefully radioactive (see A. Precious Metals part I3B of schedule 4); B. Iron or Steel (II) the alkali metals. I.e., cesium, lithium, potas C. Copper sium, rubidium, and sodium (see part 2A of sched D. Aluminum ule 4); or E. Nickel (lii) certain articles and parts thereof, of metal, F. Tin provided for in schedule 7 and elsewhere. G. Lead 2. For the purposes of the tariff schedules, unless the H. Zinc context requires otherwise — J. Beryllium, Columbium, Germanium, Hafnium, (a) the term "precious metal" embraces gold, silver, Indium, Magnesium, Molybdenum, Rhenium, platinum and other metals of the platinum group (iridium, Tantalum, Titanium, Tungsten, Uranium, osmium, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium), and precious- and Zirconium metaI a Iloys; K, Other Base Metals (b) the term "base metal" embraces aluminum, antimony, arsenic, barium, beryllium, bismuth, boron, cadmium, calcium, chromium, cobalt, columbium, copper, gallium, germanium, Part 3 Metal Products hafnium, indium, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, A. Metallic Containers molybdenum, nickel, rhenium, the rare-earth metals (Including B. Wire Cordage; Wire Screen, Netting and scandium and yttrium), selenium, silicon, strontium, tantalum, Fencing; Bale Ties tellurium, thallium, thorium, tin, titanium, tungsten, urani C. Metal Leaf and FoU; Metallics um, vanadium, zinc, and zirconium, and base-metal alloys; D, Nails, Screws, Bolts, and Other Fasteners; (c) the term "meta I" embraces precious metals, base Locks, Builders' Hardware; Furniture, metals, and their alloys; and Luggage, and Saddlery Hardware (d) in determining which of two or more equally specific provisions for articles "of iron or steel", "of copper", E. -

Manual and Computer Aided Jewellery Design Training Module

MAST MARKET ALIGNED SKILLS TRAINING MANUAL AND COMPUTER AIDED JEWELLERY DESIGN TRAINING MODULE In partnership with Supported by: INDIA: 1003-1005,DLF City Court, MG Road, Gurgaon 122002 Tel (91) 124 4551850 Fax (91) 124 4551888 NEW YORK: 216 E.45th Street, 7th Floor, New York, NY 10017 www.aif.org MANUAL AND COMPUTER AIDED JEWELLERY DESIGN TRAINING MODULE About the American India Foundation The American India Foundation is committed to catalyzing social and economic change in India, and building a lasting bridge between the United States and India through high impact interventions ineducation, livelihoods, public health, and leadership development. Working closely with localcommunities, AIF partners with NGOs to develop and test innovative solutions and withgovernments to create and scale sustainable impact. Founded in 2001 at the initiative of PresidentBill Clinton following a suggestion from Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee, AIF has impacted the lives of 4.6million of India’s poor. Learn more at www.AIF.org About the Market Aligned Skills Training (MAST) program Market Aligned Skills Training (MAST) provides unemployed young people with a comprehensive skillstraining that equips them with the knowledge and skills needed to secure employment and succeed on thejob. MAST not only meets the growing demands of the diversifying local industries across the country, itharnesses India’s youth population to become powerful engines of the economy. AIF Team: Hanumant Rawat, Aamir Aijaz & Rowena Kay Mascarenhas American India Foundation 10th Floor, DLF City Court, MG Road, Near Sikanderpur Metro Station, Gurgaon 122002 216 E. 45th Street, 7th Floor New York, NY 10017 530 Lytton Avenue, Palo Alto, CA 9430 This document is created for the use of underprivileged youth under American India Foundation’s Market Aligned Skills Training (MAST) Program. -

Recommended Starter Tool List.Pdf

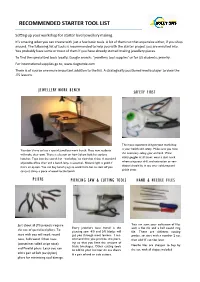

RECOMMENDED STARTER TOOL LIST Setting up your workshop for starter level jewellery making. It’s amazing what you can create with just a few basic tools. A lot of them not that expensive either, if you shop around. The following list of tools is recommended to help you with the starter project you are enrolled into. You probably have some or most of them if you have already started making jewellery pieces. To find the specialized tools locally, Google search; ‘jewellery tool supplies’ or for US students; jewelry. For international supplies go to; www.riogrande.com There is of course one more important addition to the list. A strategically positioned media player to view the JTS lessons. JEWELLERY WORK BENCH SAFETY FIRST The most important thing in your workshop is your health and safety. Make sure you have You don’t have to buy a special jewellery work bench. Most new students will make their own. There is a lesson on how Soham built his student the necessary safety gear on hand. Wear safely goggles at all times, wear a dust mask benches. Type into the search bar ‘ workshop’ to view that video. A standard adjustable office chair and a bench lamp is essential,. Natural light is good if when using your drill, and extraction or ven- tilation should be in use over soldering and that’s an option. You can buy bench pegs to work from but to start off you can just clamp a piece of wood to the bench. pickle areas. PLIERS PIERCING SAW & CUTTING TOOLS HAND & NEEDLE FILES Just about all JTS projects require You can start your collection of files Every jewellers best friend is the with a flat file and a half round ring the use of specialised pliers. -

Tool, Dies and Moulds Report

TOOL, DIES AND MOULDS REPORT 1. WHAT IS TOOLING? The equipment required to convert raw material into a required shape is commonly referred to as tooling. The process of equipment manufacture that aids in the conversion of a raw material into a required shape is commonly referred to as tool, die and mould making. Materials converted include: • Metals • Aluminium • Polymers (Plastics) Tooling is found in almost all manufacturing industries including: • Automotive • Aerospace • Rail & Marine • Defense • Mining • Agro-processing • Mineral beneficiation • Leisure • Packaging (foodstuffs, consumer goods and electronics) The manufacturing industry is dependant on the availability of a good tool, die and mould making industry. Tools, dies and moulds directly contribute to: • Manufacturing output capacity, • Quality standard of a product produced, • Price competitiveness of the product produced, • Lifecycle cost of a product produced. 1 2. DEFINITION OF INDIVIDUAL AREAS OF TOOL, DIES AND MOULDS. I. WHAT IS A TOOL? A machine tool is a powered mechanical device, typically used to fabricate metal components of machines by machining, which is the selective removal of metal. The term machine tool is usually reserved for tools that used a power source other than human movement, but they can be powered by people if appropriately set up. Many historians of technology consider that the true machine tools were born when direct human involvement was removed from the shaping or stamping process of the different kinds of tools. Machine tools can be powered from a variety of sources. Human and animal power are options, as is energy captured through the use of waterwheels. However, machine tools really began to develop after the development of the steam engine, leading to the Industrial Revolution. -

Basic Metal Toolkit

Intro to Metalsmithing Basic Metal Toolkit Jeweler’s Saw $20.00 Saw Blades 4.75 Vernier Caliper 10.50 Steel Metric Ruler 7.95 Hardwood Ring Mandrel 16.00 Scribe 8.95 Plier & Cutter Kit 29.00 Needle File Kit 14.95 Dividers 11.00 Bur Life 5.50 A Pin Vise 9.95 Bench Pin with Anvil 16.95 Twist Drills 6.45 Center Punch 8.95 B Hammer Kit 59.00 C Sand Paper Assortment 17.60 D Pocket Wire Gauge 14.95 Steel Square 4.55 Optivisor 6.45 Metalsmith Essentials - Tim McCreight 15.00 Estimated Total $288.45 ! A. Can substitute beeswax for Bur Life! B. Can make your own from an old nail.! C. You can pick up hammers from home improvement stores and alter them.! !D. You can buy sandpaper at home improvement stores for less and in bulk.! ! "1 of "7 Intro to Metalsmithing Measurement Resources Conversion Website www.convert-me.com Will convert units of distance and length instantly. Metric Conversions www.metric-conversions.org Excellent free resource to convert from Imperial to Metric ! ! Formulas! ! "2 of "7 Intro to Metalsmithing ! Terminology (Small List)! ! Alloy Mixture of metals; sterling silver is an allow of fine silver and copper. Annealing The process of heating and then cooling metal to make it softer and thus easier to work with. Base Metal Nonprecious metal, such as aluminum, copper, iron and nickel. Bezel The rim of metal that is used to secure a stone in a rub-over setting. Blank A flat shape cut from sheet metal. -

Fibre-Reinforced Materials Fabricated by Powder Extrusion

FIBRE-REINFORCED MATERIALS FABRICATED BY POWDER EXTRUSION by HENRY MCSHANE, B.SC,(ENG.) A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London John Percy Research Group, Department of Metallurgy and Materials Science, March 1978 Imperial College of Science and Technology, London SW7 2BP ABSTRACT The powder extrusion process as a consolidation technique for pre-alloyed aluminium and aluminium alloy powders has been thoroughly investigated. Analyses have been proffered to pre- dict. extrusion load, strain rate and "steady state" temperature during the extrusion process. Classical hot working theory has been applied to powder compacts during extrusion and to the re- sulting extrudes relating flow stress, strain rate and tempera- ture. The controlling effect of the extrusion parameters on the product structure and mechanical properties has been clearly demonstrated. Al-Mg-Si powder extrudes have been subjected to various heat treatments and the resulting mechanical properties investigated. Glass fibre reinforced rods have been produced, by this powder extrusion route, from mechanically mixed quantities of aluminium alloy powder and glass powder. The extrusion process has served three purposes:- (1) Fibre formation (in situ in the deformation zone and die neck) (2) Fibre alignment (3) Matrix consolidation The structure and mechanical properties of the resulting rein- forced extrudes have been observed in some detail. A knowledge of the glass content, extrusion temperature and ram speed required to give optimum properties has been obtained. In all)the results of several hundred extrusions, the cor- responding mechanical tests and microscopical examinations are reported in this thesis. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to:- for: - Dr. -

Saw and Pierce Jewellery Or Silverware Components

CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components Overview This unit covers the skills and knowledge required to use the different types of sawing equipment appropriate to your work to cut and pierce materials. You will be required to work to instructions, use a range of saws appropriate to the design of the product. You will be expected to check the quality and accuracy of your work against given tolerances. You need to be able to recognise any defects, to determine the appropriate action to rectify them and ensure that the finished work meets the given specification. CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components 1 CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components Performance criteria You must be able to: P1 follow instructions for sawing and piercing complex components P2 identify and select the correct saw blades P3 cut out range of items using a piercing saw frame P4 complete the work to the given specification CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components 2 CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components Knowledge and understanding You need to know and K1 the specific safety precautions to be taken when using sheet metal, understand: sawing and piercing tools and equipment K2 the methods of marking out, drilling and piercing complicated shapes and patterns K3 the type of saw to be used, and selecting appropriate saw blades K4 the importance of keeping the work area safe and tidy to retain valuable waste (lemel) K5 how to check that the pierced and sawn product meets the required standard CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components 3 CCSJ3.5 Saw and pierce jewellery or silverware components Additional Information Scope/range You are required to: related to performance 1. -

EFFECT of COPPER ADDITIONS on DEFORMATION PROCESSING of ALUMINIUM ALLOYS by RICHARD PAUL VIEROD, B.Sc (ENG), A.R.S.M. a Thesis S

EFFECT OF COPPER ADDITIONS ON DEFORMATION PROCESSING OF ALUMINIUM ALLOYS BY RICHARD PAUL VIEROD, B.Sc (ENG), A.R.S.M. A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London John Percy Research Group Department of Metallurgy and Material Science Royal School of Mines Imperial College London, SW7 2BP May 1983 1 * ABSTRACT The effect of an increase in copper content from 1 wt% Cu to 5 wt% Cu on the hot working characteristics of a 2000 series alloy based on AA2014 have been investigated, as well as a binary 4 wt% Cu alloy. The torque twist data generated from the hot torsion tests has been analysed using a * graphical and mathematical minimisation technique, the temperature during testing being allowed for in the latter technique. The development of a strain dependent constitutive equation used in the temperature- rise model has been investigated. k The dependence of the direct extrusion peak pressure and peak height on extrusion ratio, billet temperature and Zp the temperature compensated strain rate has been investigated in the 2000 series alloys and for direct and indirect extrusion of the 2014 alloy. The effect of container temperature and billet length on the peak pressure has also been investigated. The development of a general f pressure equation applicable over a wide range of extrusion conditions and to a complete alloy system is investigated in the 2000 series alloys and a non heat treatable 5052 alloy. A solution preheat treatment determined from hot torsion tests has been used on the 2014 alloy to investigate whether surface cracking can be reduced during direct extrusion. -

Friction Fitting Test

Friction Fitting Test This tutorial demonstrates how to make a simple 2D to 3D pendant without soldering. It is important that students learn cold joint techniques such as friction fitting & riveting before they are taught to solder. This ensures that solder isn’t used as filler and that joints are prepared correctly before soldering. 1. This project starts with a piece of brass sheet 1.2mm x 48mm x 16mm. Along with patience, you will need your measuring & marking tools including a good pair of dividers a drill and piercing saw. 2. The sheet of brass needs to be squared off using a set square. This will ensure that the preliminary markings are accurate. Scribe a centre line long ways and mark two lines short ways to create three perfect squares. Scribe a cross through each square to identify the three centre points. 3. Centre punch at each cross point. Set your dividers to scribe a circle inside the squares, making sure that you allow for the saw blade thickness and final file trimming. The circle diameter should be approximately 14.5mm. 4. You now need to mark out the slots. Set your dividers to the metal thickness (1.2mm) this can be difficult if your dividers aren’t cut out for precision work. Put the points of the dividers either side of the centre mark then place your ruler square to the work against your dividers. Scribe off the two ends & out from the middle. 5. Mark out a ‘D’ shaped opening for a chain on the centre section, no less than 2mm between the outer edge and centre. -

Eclipse Plus Brochure 09

Product Guide CONTENTS Metal Cutting Hand & Power Hacksaw Blades 3-6 Saw Frames & Small Saw Blades 7-9 Holesaws & Arbors 10-11 Cutting & Grinding Abrasive Discs 12-13 Bolt & Cable Cutters 14-15 Snips 16 Chisels Cold Chisels 18 Wrecking Bars 18 Wood Chisels 19 Locking Jaw Pliers Locking Jaw Pliers 21-23 C-Clamps 21-23 Locking Tools 23 Pliers Pliers 25 Special Purpose Pliers 26-27 Professional Electricians’ Tools Premium Quality Safety Tools Introduction 29 VDE Cutters & Pliers 30-32 VDE Screwdrivers 33-34 Specialist Electricians’ Hand tools 35-36 Electricians’ Tool Case 37 Vices & Clamps Vices 39-40 Clamps 41-43 Gripping & Plumbing Wrenches 45-47 Pipe Vices 47 Pipe Cutters 48 Hand Bender & Accessories 48 Riveters & Threaded Insert Setting Tools Riveters 50 Threaded Insert Setting Tools & Kits 51 Riveter Kits / Spares / Rivets / Deburring Tools 52 Torque Control Tools, Accessories & Multipliers Torque Tool information 54-59 Recommended Maximum Torque Values 57 Torque Wrench Selection Guide 58-59 Torque Wrenches 60-63 Torque Handles (Female Fitting) 64 Automotive Torque Wrenches 64 Industrial Torque Wrenches 65 Professional Industrial Torque Wrenches 66 Ratchet Repair Kits 67 Socket Sets 67 Torque Screwdrivers 68 Multipliers 69-71 Engineers’ Tools Punches 73 Scrapers / Pin Vices / Chucks & Collets 74 Scribers / Jewellers Screwdrivers 75 Toolbits / Holders / Boring Bars 76 Cutting Off Tools / Lathe Tools / Holders 77 Tap Wrenches & Accessories 78 Eclipse Magnetics Permanent Magnets 79-81 Magnetic Tools 82-84 Drill Bits Premium SDS Plus Hammer Drill Bits 86-87 Standard SDS Plus Hammer Drill Bits 87 Masonry Drill Bits 88 HSS Drill Bits 88 Hinge Boring Bits 88 General Hand Tools Utility Knives & Blades 90 Tape Measures 90 THE OFFICIAL MARK OF QUALITY Dedication to quality has earned official accreditation of the BSEN ISO 9001:2008 Quality Assurance Certificate for the general manufacture of all our hand tools. -

Ssc-464 High Speed Aluminum Vessels Design Guide Ship

NTIS # PB2012- SSC-464 HIGH SPEED ALUMINUM VESSELS DESIGN GUIDE This document has been approved For public release and sale; its Distribution is unlimited SHIP STRUCTURE COMMITTEE 2012 Ship Structure Committee RADM P.F. Zukunft RDML Thomas Eccles U. S. Coast Guard Assistant Commandant, Chief Engineer and Deputy Commander Assistant Commandant for Marine Safety, Security For Naval Systems Engineering (SEA05) and Stewardship Co-Chair, Ship Structure Committee Co-Chair, Ship Structure Committee Mr. H. Paul Cojeen Dr. Roger Basu Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers Senior Vice President American Bureau of Shipping Mr. Christopher McMahon Mr. Victor Santos Pedro Director, Office of Ship Construction Director Design, Equipment and Boating Safety, Maritime Administration Marine Safety, Transport Canada Mr. Kevin Baetsen Dr. Neil Pegg Director of Engineering Group Leader - Structural Mechanics Military Sealift Command Defence Research & Development Canada - Atlantic Mr. Jeffrey Lantz, Mr. Edward Godfrey Commercial Regulations and Standards for the Director, Structural Integrity and Performance Division Assistant Commandant for Marine Safety, Security and Stewardship Dr. John Pazik Mr. Jeffery Orner Director, Ship Systems and Engineering Research Deputy Assistant Commandant for Engineering and Division Logistics SHIP STRUCTURE SUB-COMMITTEE AMERICAN BUREAU OF SHIPPING (ABS) DEFENCE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT CANADA ATLANTIC Mr. Craig Bone Dr. David Stredulinsky Mr. Phil Rynn Mr. John Porter Mr. Tom Ingram MARITIME ADMINISTRATION (MARAD) MILITARY SEALIFT COMMAND (MSC) Mr. Chao Lin Mr. Michael W. Touma Mr. Richard Sonnenschein Mr. Jitesh Kerai NAVY/ONR / NAVSEA/ NSWCCD TRANSPORT CANADA Mr. David Qualley / Dr. Paul Hess Natasa Kozarski Mr. Erik Rasmussen / Dr. Roshdy Barsoum Luc Tremblay Mr. Nat Nappi, Jr. Mr.