Learning to Sing the Blues” Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

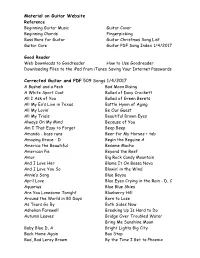

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Tributaries on the Name of the Journal: “Alabama’S Waterways Intersect Its Folk- Ways at Every Level

Tributaries On the name of the journal: “Alabama’s waterways intersect its folk- ways at every level. Early settlement and cultural diffusion conformed to drainage patterns. The Coastal Plain, the Black Belt, the Foothills, and the Tennessee Valley re- main distinct traditional as well as economic regions today. The state’s cultural landscape, like its physical one, features a network of “tributaries” rather than a single dominant mainstream.” —Jim Carnes, from the Premiere Issue JournalTributaries of the Alabama Folklife Association Joey Brackner Editor 2002 Copyright 2002 by the Alabama Folklife Association. All Rights Reserved. Issue No. 5 in this Series. ISBN 0-9672672-4-2 Published for the Alabama Folklife Association by NewSouth Books, Montgomery, Alabama, with support from the Folklife Program of the Alabama State Council on the Arts. The Alabama Folklife Association c/o The Alabama Center for Traditional Culture 410 N. Hull Street Montgomery, AL 36104 Kern Jackson Al Thomas President Treasurer Joyce Cauthen Executive Director Contents Editor’s Note ................................................................................... 7 The Life and Death of Pioneer Bluesman Butler “String Beans” May: “Been Here, Made His Quick Duck, And Got Away” .......... Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott 9 Butler County Blues ................................................... Kevin Nutt 49 Tracking Down a Legend: The “Jaybird” Coleman Story ................James Patrick Cather 62 A Life of the Blues .............................................. Willie Earl King 69 Livingston, Alabama, Blues:The Significance of Vera Ward Hall ................................. Jerrilyn McGregory 72 A Blues Photo Essay ................................................. Axel Küstner Insert A Vera Hall Discography ...... Steve Grauberger and Kevin Nutt 82 Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress .................John Garst 92 Recording Review ........................................................ -

1 Fulfillment of Prophecy Singing the Sacred Core 52 – Week 10 We

1 Fulfillment of Prophecy Singing the Sacred Core 52 – Week 10 We have songs for every occasion. Music for every mood. You’ve just been through a bad breakup, you grab your Kleenex and you put Someone Like You by Adele on repeat. You’re singing your child to sleep at bedtime, you swing a sweet lullaby like Rock-a-bye-baby while you secretly wonder what kind of freak puts their baby in a treetop. You’re getting pumped up for the big game , so you’re going to blast Get Ready by 2 Unlimited. You want to rock out, you crank the volume up to 11 and listen to For Those About to Rock. You’re feeling romantic, you dig out the old vinyl, you drop the lights and you drop the needle on When a Man Loves a Woman. You’re about to hit the gym and get your sweat on, you’ll pump some Survivor by Destiny’s Child. In the same way, there are many kings of songs in the book of Psalms. There were songs to be sung to prepare you for worship. There are songs of thanksgiving. There are wisdom psalms. There are even what are called the Psalms of Lament, which is their version of the sad songs. They are what Israel sang when they felt like singing the blues. They had all these different kinds of songs for all these different occasions. One kind of song we find in the Psalms might be unfamiliar to us. They are the royal psalms. -

The Story of the Blues

LESSON 5 TEACHER’S GUIDE The Story of the Blues by Myron Banks Fountas-Pinnell Level U Nonfiction Selection Summary The blues is an American sound—instruments like piano, trumpet, saxophone, and a voice combine to express deep meaning about life. Number of Words: 1,357 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Nonfi ction Text Structure • Third-person voice in a continuous narrative • Several topics, including the development and evolution of the blues • Underlying structures include description, sequence, and compare/contrast Content • History of blues music in the United States • Infl uence of blues music on other styles of music Themes and Ideas • Themes of racism, social class barriers, and weaving of blues into popular culture • The blues offers a timeless, enjoyable diversion for many people. • The blues has a rich and varied history that can be traced to Africa. Language and • Descriptive language, including fi gurative language Literary Features • Some inference required to comprehend trends in blues over time Sentence Complexity • Some complex sentences contain embedded, dependent clauses • Lyrics included to show patterns in blues lyrics Vocabulary • Technical words and concepts about music: lyrics, verses, solo, rhythm, records Words • Some words which may be unfamiliar: saxophone, plantations, audiences • Some multisyllable words: genuinely, innovation, parallel, predominantly, tendency Illustrations • Full range of graphics, some dense and challenging Book and Print Features • Fourteen pages of text, with graphics or photographs on most pages • Table of contents, headings, captions, timeline, and map © 2006. Fountas, I.C. & Pinnell, G.S. Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company All rights reserved. -

Language-Of-The-Blues.Pdf

` ` Ebook published February 1, 2012 by Guitar International Group, LLC Editors: Rick Landers and Matt Warnock Cover Design: Debra Devi Originally published January 1, 2006 by Billboard Books Executive Editor: Bob Nirkind Editor: Meryl Greenblatt Design: Cooley Design Lab Production Manager: Harold Campbell Copyright (c) 2006 by Debra Devi Cover photograph of B.B. King by Dick Waterman courtesy Dick Waterman Music Photography Author photograph by Matt Warnock Additional photographs by: Steve LaVere, courtesy Delta Haze Corporation Joseph A. Rosen, courtesy Joseph A. Rosen Photography Sandy Schoenfeld, courtesy Howling Wolf Photos Mike Shea, courtesy Tritone Photography Toni Ann Mamary, courtesy Hubert Sumlin Blues Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: 6DPXHO&KDUWHUV³7KH6RQJRI$OKDML)DEDOD.DQXWHK´H[FHUSWIURPThe Roots of the Blues by Samuel Charters, originally published: Boston: M. Boyars, 1981. Transaction Publishers: Excerpt from Deep Down in the Jungle: Negro Narrative Folklore from the Streets of Philadelphia by Roger Abrahams. Warner-7DPHUODQH3XEOLVKLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ6NXOO0XVLF/\ULFIURP³,:DON2Q*XLOGed 6SOLQWHUV´E\0DF5HEHQQDFN Library of Congress Control Number: 2005924574 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means- graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage-and-retrieval systems- without the prior permission of the author. ` Guitar International Reston, Virginia ` Winner of the 2007 ASC AP Deems Taylor Award for Outstanding Book on Popular Music ³:KDWDJUHDWUHVRXUFH«DVfascinating as it is informative. Debra's passion for the blues VKLQHVWKURXJK´ ±Bonnie Raitt ³(YHU\EOXHVJXLWDULVWQHHGVWRNQRZWKHLUEOXHVKLVWRU\DQGZKHUHWKHEOXHVDUHFRPLQJ IURP'HEUD¶VERRNZLOOWHDFK\RXZKDW\RXUHDOO\QHHGWRNQRZ´± Joe Bonamassa ³7KLVLVDEHDXWLIXOERRN$IWHUKHDULQJµ+HOOKRXQGRQ0\7UDLO¶LQKLJKVFKRRO,ERXJKW every vintage blues record available at the time. -

1. a Teenager in Love Dion & the Belmonts 2. Ain't That a Shame

1. A Teenager in Love Dion & The Belmonts 66. Misty Johnny Mathis 2. Ain’t That A Shame Fats Domino 67. Moonlight Serenade Glenn Miller 3. All I Have To Do Is Dream Everly Brothers 68. Mr. Blue Fleetwoods 4. All Shook Up Elvis Presley 69. My Prayer Platters 5. All The Way Frank Sinatra 70. On The Street Where You Live Vic Damone & Percy Faith 6. At The Hop Danny & The Juniors 71. One Summer Night Danleers 7. Banana Boat (Day-O) Harry Belafonte 72. Only You Platters 8. Because Of You T. Bennett & P. Faith Orch 73. Over And Over Bobby Day 9. Beyond The Sea Bobby Darin 74. Papa Loves Mambo Perry Como 10. Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 75. Party Doll Buddy Knox 11. Book Of Love Monotones 76. Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 12. Born Too Late Poni-Tails 77. Personality Lloyd Price 13. Bye Bye Love Everly Brothers 78. Poison Ivy Coasters 14. Canadian Sunset Andy Williams 79. Put Your Head On My Shoulder Paul Anka 15. Chances Are Johnny Mathis 80. Rags To Riches Tony Bennet 16. Chantilly Lace Big Bopper 81. Rock & Roll Music Chuck Berry 17. Charlie Brown Coasters 82. Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & The Comets 18. Cherry Pink & Apple Blossom Perez “Prez” Prado 83. Rockin’ Robin Bobby Day 19. Come Go With Me Dell-Vikings 84. See You Later, Alligator Bill Haley & The comets 20. Diana Paul Anka 85. Shake, Rattle And Roll Bill Haley & The Comets 21. Do You Want To Dance Bobby Freeman 86. Silhouettes Diamonds 22. Donna Ritchie Valens 87. -

' the Impact of Radio, ' ' ; Motion Pictures, and Television ' ' 5? on the Development 0? Hm; Td Blues and Rock And. Roll Mu

..’ - v w _. _-u-- ---~v--~ . —~-«- - v- vvv' .. - 0 ‘r l vu'w V UVOQ 0 I '1' ‘ V.‘_ 9 I“? . F’f.~'I00-oa~on v. , fwngvgoooqok .9. 'W'-‘ . _ . Q”. .. ‘ '.- . r . l. 7 I . ‘ a. ' . n D I r- ‘ - . G I ‘ THE IMPACT OF RADIO, ' ‘ ; MOTION PICTURES, AND TELEVISION ' ' 5? ON THE DEVELOPMENT 0? HM; TD BLUES AND ROCK AND. ROLL MUSIC ‘ r for the Degree of M. A. ' ' MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY LAWRENCE NEWTON REDD . .. ' u 191 1 . I v r . n . r- , a , I . ,. - I . ‘ . I ' _ . 1 ~ . I _ . ‘ .-- E . ,I -. I ' ‘ I - - ‘ . - _ l fl . .- ' , .9! ‘ __ l ' a , n ' n 0' I _ o o .I ’ . ' " . ' ‘ ‘ ' - - ' I 'n u . I - o I- ' ' - a ‘ . _ _, .I I. ' ' . u ' ' ' - I- " o l _ . _ . ' ' . ' . _ - . ' _ . — ’ ‘ n ' ' ‘ ' . —' . U I . o I v. - ‘ ' 0-0 ' .- . ‘ .. o — g . I.- _ _- l . I .. v- ‘. ‘ .. - 'o ’ ' ' ' '“ . _ . ‘ ._ I. 0-. ' r . ‘ v ' r .. - " - .- . a l , . ' ' - v 1 -o 0 -."°' ""-‘ . c- " .. , . I. o - ' ' ‘ _ _ - I. 4v.~ ' ‘ - . o . r a a . .oa... I-I "I ' ‘ ‘ v. I ' ' ' ' ' ' . r I ‘. .o- ‘ . ' ' ' I . A - C . " ' . .‘.I . .. ‘ '. .. .. .I. .. I ’. I . u I. , . l _ . o . c ,., o . t .. - ..,. "" tv rv' " 'I .'_ ‘ l . ,, . ' ‘ .’ . I 0 "' . - . , . ' . ' ' , . ‘. I. .o ' I’ll .' , . , . .. , - ' I'. " ' ‘ _ _. , - I I :o.r _ , ‘ . I . , ov. r. .. l o ' .. v . ,‘....oo- .9 , .I. , o '. 0. .. .. .. "..., . - .g, .a-. ... .....o .7 .'. a .. ' , o E ‘ l A .,.. I 'I ,. __. ‘ _ .. ,_-'..- - 0’ I- o - .e‘l‘o‘.‘ "P' ' ' " .o-- It ._'."t-.'-".0 l ' ' . ’ . ... ,.,,_.,.I -- n- . -99- .’°Ov‘ . - . on. -

A SOUND for RECOGNITION: BLUES MUSIC and the AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY Remy Corbet Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Theses Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2011 A SOUND FOR RECOGNITION: BLUES MUSIC AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY Remy Corbet Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Corbet, Remy, "A SOUND FOR RECOGNITION: BLUES MUSIC AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY" (2011). Theses. Paper 730. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SOUND FOR RECOGNITION BLUES MUSIC AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY by Rémy Corbet Masters Degree, Southern Illinois University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters in History in the Graduate School Department of History Southern Illinois University Carbondale December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL A SOUND FOR RECOGNITION: BLUES MUSIC AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY By Rémy Corbet A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters Degree in the field of History Approved by: Dr. Robbie Lieberman, Chair Dr. Jonathan Bean Dr. Michael Brown Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale 08/04/2011 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Remy Corbet for the Masters in History degree in American History, presented on August 3, 2011, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: A SOUND FOR RECOGNITION: BLUES MUSIC AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Robbie Lieberman Blues music is a reflection of all the changes that shaped the African American experience. -

The World of SOUL PRICE: $1 25

BillboardTheSOUL WorldPRICE: of $1 25 Documenting the impact of Blues and R&Bupon ourmusical culture The Great Sound of Soul isonATLANTIC *Aretha Franklin *WilsonPickett Sledge *1°e16::::rifters* Percy *Young Rascals Estherc Phillipsi * Barbara.44Lewis Wi gal Sow B * rBotr ho*ethrserSE:t BUM S010111011 Henry(Dial) Clarence"Frogman" Sweet Inspirations * Benny Latimore (Dade) Ste tti L lBriglit *Pa JuniorWells he Bhiebelles aBel F M 1841 Broadway,ATLANTIC The Great Sound of Soul isonATCO Conley Arthur *KingCurtis * Jimmy Hughes (Fame) *BellE Mg DeOniaCkS" MaryWells capitols The pat FreemanlFamel DonVarner (SouthCamp) *Darrell Banks *Dee DeeSharp (SouthCamp) * AlJohnson * Percy Wiggins *-Clarence Carter(Fame) ATCONew York, N.Y. 10023 THE BLUES: A Document in Depth THIS,the first annual issue of The World of Soul, is the initial step by Billboard to document in depth the blues and its many derivatives. Blues, as a musical form, has had and continues to have a profound effect on the entire music industry, both in the United States and abroad. Blues constitute a rich cultural entity in its pure form; but its influence goes far beyond this-for itis the bedrock of jazz, the basis of much of folk and country music and it is closely akin to gospel. But finally and most importantly, blues and its derivatives- and the concept of soul-are major factors in today's pop music. In fact, it is no exaggeration to state flatly that blues, a truly American idiom, is the most pervasive element in American music COVER PHOTO today. Ray Charles symbolizes the World Therefore we have embarked on this study of blues. -

The Essence of Country Music

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2007 Fall and Redemption: The Essence of Country Music Patrick Jude Campbell The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Campbell, Patrick Jude, "Fall and Redemption: The Essence of Country Music" (2007). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1222. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1222 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALL AND REDEMPTION: THE ESSENCE OF COUNTRY MUSIC By Patrick Jude Campbell Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1992 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Fine Arts, Integrated Arts and Education The University of Montana Missoula, MT Summer 2007 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School Dorothy Morrison Department of Fine Arts Dr. Randy Bolton Department of Fine Arts Dr. James Kriley Department of Fine Arts Campbell, Patrick, M.A., July 2007 Integrated Arts and Education Fall and Redemption: The Essence of Country Music Chairperson: Dorothy Morrison My initial focus as a final project in the Creative Pulse was to begin to sing again. Singing fulfilled the three requirements of choice in a project: risk, rigor, and the requirement of ‘having to do it’. -

Two Steps from the Blues: Creating Discourse and Constructing Canons in Blues Criticism

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2001 Two steps from the blues: Creating discourse and constructing canons in blues criticism John M. Dougan College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Dougan, John M., "Two steps from the blues: Creating discourse and constructing canons in blues criticism" (2001). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623381. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nqf0-d245 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. TWO STEPS FROM THE BLUES: CREATING DISCOURSE AND CONSTRUCTING CANONS IN BLUES CRITICISM A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William & Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by John M. Dougan 2001 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3026404 Copyright 2001 by Dougan, John M. All rights reserved. UMI___ ® UMI Microform 3026404 Copyright 2001 by Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. -

The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We

The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Shirley Wade McLoughlin Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________ Director Denise Taliaferro Baszile ___________________________________________ Reader Dennis Carlson ___________________________________________ Reader Richard Quantz ___________________________________________ Reader Tammy Kernodle ____________________________________________ Graduate School Representative Barbara Hueberger Abstract A PEDAGOGY OF THE BLUES By Shirley Wade McLoughlin This dissertation presents the conceptualization of a pedagogy of the blues as an alternative to the techno-rational approach to education. This conceptualization is derived from the blues metaphor in which distinct themes are identified and utilized in formulating and enacting a pedagogy of the blues. This pedagogy is presented as an embodied art of teaching whereby there is recovery of the self by the teacher and student, as opposed to the loss of self so prevalent in present day approaches to schooling. The author grounds this work in the powerful early blues of African Americans, identifying specific themes representative of the blues metaphor that reverberate in the work of early blues artists. Starting with the historical roots of the blues, examining the texts of the blues and the lifestyles of early blues singers that embodied the blues, the author traces common themes from these sources. Next, the author presents the evolvement of the