Brian Darrith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

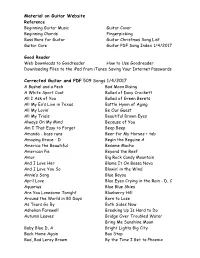

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

Prophet Singer: the Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie

Prophet Singer Prophet Singer THE VOICE AND VISION OF WOODY GUTHRIE MARK ALLAN JACKSON UNIVERSITY PRESS OF MISSISSIPPI / JACKSON AMERICAN MADE MUSIC SERIES ADVISORY BOARD DAVID EVANS, GENERAL EDITOR JOHN EDWARD HASSE BARRY JEAN ANCELET KIP LORNELL EDWARD A. BERLIN FRANK MC ARTHUR JOYCE J. BOLDEN BILL MALONE ROB BOWMAN EDDIE S. MEADOWS SUSAN C. COOK MANUEL H. PEÑA CURTIS ELLISON DAVID SANJEK WILLIAM FERRIS WAYNE D. SHIRLEY MICHAEL HARRIS ROBERT WALSER www.upress.state.ms.us The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses. Frontis: An illustration of the vigilante actions of various “Citizens Committees,” c. 1946. Sketch by Woody Guthrie. Courtesy of the Ralph Rinzler Archives. Copyright © 2007 by University Press of Mississippi All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition 2007 ϱ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jackson, Mark Allan. Prophet singer : the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie / Mark Allan Jackson. — 1st ed. p. cm. — (American made music series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-57806-915-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-57806-915-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Guthrie, Woody, 1912–1967. 2. Folk singers—United States—Biography. 3. Folk music—Social aspects—United States. I. Title. ML410.G978J33 2007 782.42162Ј130092—dc22 [B] 2006020846 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS [ vii ] PROLOGUE [ 3 ] GIVING A VOICE TO LIVING SONGS CHAPTER ONE [ 19 ] Is This Song Your -

2010/03/06 Here Comes the Weekend / Dave Edmunds Get It

2010/03/06 Here Comes The Weekend / Dave Edmunds Get It Tuxedo Junction / Jools Holland & His Rhythm & Blues Orchestra Small World Big Band Volume Two - More Friends Count Me In / Jools Holland & His Rhythm & Blues Orchestra w. Ruby Turner Small World Big Band Volume Two - More Friends Drown In My Own Tears / Jools Holland & His Rhythm & Blues Orchestra w. Jeff Beck Small World Big Band Volume Two - More Friends The Chosen Few / Flanagan The Chosen Few Ali From Mali / Flanagan Like A Fool Sabu Yerkoy / Ali Farka Toure & Toumani Diabate Ali And Toumani '56 / Ali Farka Toure & Toumani Diabate Ali And Toumani Folon / Salif Keita La Difference Djele / Salif Keita La Difference Deni Kemba / Victor Deme Victor Deme Peuple Burkinabe / Victor Deme Victor Deme Cindy Gal / Carolina Chocolate Drops Genuine Negro Jig Exiles Return / Karan Casey & John Doyle Exiles Return Madam I'm A Darling / Karan Casey & John Doyle Exiles Return Imprints / Mahsa Vahdat & Mighty Sam McClain Scent of Reunion Thought I Heard Your Voice / Mighty Sam McClain One More Bridge To Cross A Soul That's Been Abused / Hubert Sumlin Hubert Sumlin's Blues Party 2010/03/13 Lucille / Little Richard Eruption! 20 Magnum Hits Valleys Of Neptune / Jimi Hendrix Valleys of Neptune Lullaby For The Summer / Jimi Hendrix Valleys of Neptune Love Me Darling / Howlin' Wolf My Chess Box Since You've Been Gone (Sweet Sweet Baby) / Aretha Franklin Lady Soul The House That Jack Built / Thelma Jones Respect - Aretha's Influences and Inspiration The House That Jack Built / Aretha Franklin Queen of -

Blind Lemon Jefferson from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Blind Lemon Jefferson From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Birth name Lemon Henry Jefferson Also known as Deacon L. J. Bates Born September 24, 1893[1] Coutchman, Texas, U.S. Origin Texas Died December 19, 1929 (aged 36) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. Genres Blues, gospel blues Occupation(s) Singer-songwriter, musician Instruments Guitar Years active 1900s–1929 Labels Paramount Records, Okeh Records Notable instruments Acoustic Guitar "Blind" Lemon Jefferson (born Lemon Henry Jefferson; September 24, 1893 – December 19, 1929) was an American blues and gospel blues singer and guitarist from Texas. He was one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s, and has been called "Father of the Texas Blues". Jefferson's performances were distinctive as a result of his high-pitched voice and the originality on his guitar playing. Although his recordings sold well, he was not so influential on some younger blues singers of his generation, who could not imitate him as easily as they could other commercially successful artists. Later blues and rock and roll musicians, however, did attempt to imitate both his songs and his musical style. Biography Early life Jefferson was born blind, near Coutchman in Freestone County, near present-day Wortham, Texas. He was one of eight children born to sharecroppers Alex and Clarissa Jefferson. Disputes regarding his exact birth date derive from contradictory census records and draft registration records. By 1900, the family was farming southeast of Streetman, Texas, and Lemon Jefferson's birth date is indicated as September 1893 in the 1900 census. The 1910 census, taken in May before his birthday, further confirms his year of birth as 1893, and indicated the family was farming northwest of Wortham, near Lemon Jefferson's birthplace. -

Blues Legacy of Phil Wiggins | Smithsonian Folkways Magazine

Winter 2018 Blues Legacy of Phil Wiggins by Jeff Place When one thinks of country blues, the usual thought is of the music of the Mississippi Delta. While many wonderful blues men and women have come out of the Delta over the last century, there has been a wonderful parallel style that exists on the East Coast of the United States, “East Coast blues,” or more recently called “Piedmont Blues”. The Piedmont is a geographic region that exists up and down the East Coast between the coastal tidewater region and the Appalachian Mountains. It includes the cities of Atlanta, Charlotte, Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. In the twentieth century many African Americans left the racial climate of the south and moved north to eastern cities like Washington. There were defense jobs in Washington and Baltimore to be had. Some of the great early East Coast blues musicians were Blind Blake from Florida, Willie McTell from Atlanta, Blind Boy Fuller and Sonny Terry from Durham, and Brownie McGhee from Knoxville. Phil Wiggins was born in Washington, D.C. in May of 1954. There was music in the house, his father, a government worker with the Department of the Interior, played piano. The Piedmont blues scene has always been strong, and still is, around Washington. In the 9th grade he discovered the harmonica and shortly thereafter met his first musical partner, Flora Molton, a street evangelist who played on an F Street corner in the shopping district. He began to play harmonica with Molton. From 1972 to 1976, he accompanied Molton at the then Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife. -

Jemf Quarterly

JEMF QUARTERLY JOHN EDWARDS MEMORIAL FOUNDATION VOL. XII SPRING 1976 No. 41 THE JEMF The John Edwards Memorial Foundation is an archive and research center located in the Folklore and Mythology Center of the University of California at Los Angeles. It is chartered as an educational non-profit corporation, supported by gifts and contributions. The purpose of the JEMF is to further the serious study and public recognition of those forms of American folk music disseminated by commercial media such as print, sound recordings, films, radio, and television. These forms include the music referred to as cowboy, western, country & western, old time, hillbilly, bluegrass, mountain, country ,cajun, sacred, gospel, race, blues, rhythm' and blues, soul, and folk rock. The Foundation works toward this goal by: gathering and cataloguing phonograph records, sheet music, song books, photographs, biographical and discographical information, and scholarly works, as well as related artifacts; compiling, publishing, and distributing bibliographical, biographical, discographical, and historical data; reprinting, with permission, pertinent articles originally appearing in books and journals; and reissuing historically significant out-of-print sound recordings. The Friends of the JEMF was organized as a voluntary non-profit association to enable persons to support the Foundation's work. Membership in the Friends is $8.50 (or more) per calendar year; this fee qualifies as a tax deduction. Gifts and contributions to the Foundation qualify as tax deductions. DIRECTORS ADVISORS Eugene W. Earle, President Archie Green, 1st Vice President Ry Cooder Fred Hoeptner, 2nd Vice President David Crisp Ken Griffis, Secretary Harlan Dani'el D. K. Wilgus, Treasurer David Evans John Hammond Wayland D. -

Tributaries on the Name of the Journal: “Alabama’S Waterways Intersect Its Folk- Ways at Every Level

Tributaries On the name of the journal: “Alabama’s waterways intersect its folk- ways at every level. Early settlement and cultural diffusion conformed to drainage patterns. The Coastal Plain, the Black Belt, the Foothills, and the Tennessee Valley re- main distinct traditional as well as economic regions today. The state’s cultural landscape, like its physical one, features a network of “tributaries” rather than a single dominant mainstream.” —Jim Carnes, from the Premiere Issue JournalTributaries of the Alabama Folklife Association Joey Brackner Editor 2002 Copyright 2002 by the Alabama Folklife Association. All Rights Reserved. Issue No. 5 in this Series. ISBN 0-9672672-4-2 Published for the Alabama Folklife Association by NewSouth Books, Montgomery, Alabama, with support from the Folklife Program of the Alabama State Council on the Arts. The Alabama Folklife Association c/o The Alabama Center for Traditional Culture 410 N. Hull Street Montgomery, AL 36104 Kern Jackson Al Thomas President Treasurer Joyce Cauthen Executive Director Contents Editor’s Note ................................................................................... 7 The Life and Death of Pioneer Bluesman Butler “String Beans” May: “Been Here, Made His Quick Duck, And Got Away” .......... Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott 9 Butler County Blues ................................................... Kevin Nutt 49 Tracking Down a Legend: The “Jaybird” Coleman Story ................James Patrick Cather 62 A Life of the Blues .............................................. Willie Earl King 69 Livingston, Alabama, Blues:The Significance of Vera Ward Hall ................................. Jerrilyn McGregory 72 A Blues Photo Essay ................................................. Axel Küstner Insert A Vera Hall Discography ...... Steve Grauberger and Kevin Nutt 82 Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress .................John Garst 92 Recording Review ........................................................ -

1 Fulfillment of Prophecy Singing the Sacred Core 52 – Week 10 We

1 Fulfillment of Prophecy Singing the Sacred Core 52 – Week 10 We have songs for every occasion. Music for every mood. You’ve just been through a bad breakup, you grab your Kleenex and you put Someone Like You by Adele on repeat. You’re singing your child to sleep at bedtime, you swing a sweet lullaby like Rock-a-bye-baby while you secretly wonder what kind of freak puts their baby in a treetop. You’re getting pumped up for the big game , so you’re going to blast Get Ready by 2 Unlimited. You want to rock out, you crank the volume up to 11 and listen to For Those About to Rock. You’re feeling romantic, you dig out the old vinyl, you drop the lights and you drop the needle on When a Man Loves a Woman. You’re about to hit the gym and get your sweat on, you’ll pump some Survivor by Destiny’s Child. In the same way, there are many kings of songs in the book of Psalms. There were songs to be sung to prepare you for worship. There are songs of thanksgiving. There are wisdom psalms. There are even what are called the Psalms of Lament, which is their version of the sad songs. They are what Israel sang when they felt like singing the blues. They had all these different kinds of songs for all these different occasions. One kind of song we find in the Psalms might be unfamiliar to us. They are the royal psalms. -

Juke Joints, Rum Shops, and Honky-Tonks, the Politics Of

Draft of a chapter in a forthcoming anthology, please do not cite “Juke Joints, Rum Shops, and Honky-Tonks: Black Migrant Labor and Leisure in Caribbean Guatemala and Honduras, 1898–1922” Frederick Douglass Opie Babson College In 1922, Eugene Cunningham and his companion, both white travelers from the United States, entered a combination bar and grocery store in Zacapa on the Caribbean coast of Guatemala. The store was operated by a white American expatriate. An African American customer, also an expatriate, invited the travelers to have a drink with him. When they ignored this request, the man ordered the two white men to join him, after which a violent altercation ensued. In the course of his travels, Cunningham also heard of a white bar operator who warned a racist Irish American expatriate that if he continued to call blacks “nigger,” “his end would come suddenly from a knife between the ribs.”1 What do anecdotes like these—anecdotes in which white men of European ancestry are threatened by black Americans in Guatemala—tell us about the relationship between alcohol and culture, class, and race on the Caribbean Coast of Guatemala in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? Black immigrants went to Guatemala in the hope of finding better economic opportunities than were available to them in their home Draft of a chapter in a forthcoming anthology, please do not cite region. The labor market in lowland Guatemala was good because Guatemalan nationals refused jobs in malaria-infested regions where railroad track was laid. Black immigrants were willing to go there and work long hours for higher wages. -

Band/Surname First Name Title Label No

BAND/SURNAME FIRST NAME TITLE LABEL NO DVD 13 Featuring Lester Butler Hightone 115 2000 Lbs Of Blues Soul Of A Sinner Own Label 162 4 Jacks Deal With It Eller Soul 177 44s Americana Rip Cat 173 67 Purple Fishes 67 Purple Fishes Doghowl 173 Abel Bill One-Man Band Own Label 156 Abrahams Mick Live In Madrid Indigo 118 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Swallow 033 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Ace 084 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues/The Good Times Killin' Me Ace 096 Abshire Nathan The Good Times Killin' Me Sonet 044 Ace Black I Am The Boss Card In Your Hand Arhoolie 100 Ace Johnny Memorial Album Ace 063 Aces Aces And Their Guests Storyville 037 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 022 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 033 Aces No One Rides For Free El Toro 163 Aces The Crawl Own Label 177 Acey Johnny My Home Li-Jan 173 Adams Arthur Stomp The Floor Delta Groove 163 Adams Faye I'm Goin' To Leave You Mr R & B 090 Adams Johnny After All The Good Is Gone Ariola 068 Adams Johnny After Dark Rounder 079/080 Adams Johnny Christmas In New Orleans Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny From The Heart Rounder 068 Adams Johnny Heart & Soul Vampi 145 Adams Johnny Heart And Soul SSS 068 Adams Johnny I Won't Cry Rounder 098 Adams Johnny Room With A View Of The Blues Demon 082 Adams Johnny Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me Rounder 097 Adams Johnny Stand By Me Chelsea 068 Adams Johnny The Many Sides Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Sweet Country Voice Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Tan Nighinggale Charly 068 Adams Johnny Walking On A Tightrope Rounder 089 Adamz & Hayes Doug & Dan Blues Duo Blue Skunk Music 166 Adderly & Watts Nat & Noble Noble And Nat Kingsnake 093 Adegbalola Gaye Bitter Sweet Blues Alligator 124 Adler Jimmy Midnight Rooster Bonedog 170 Adler Jimmy Swing It Around Bonedog 158 Agee Ray Black Night is Gone Mr. -

The Story of the Blues

LESSON 5 TEACHER’S GUIDE The Story of the Blues by Myron Banks Fountas-Pinnell Level U Nonfiction Selection Summary The blues is an American sound—instruments like piano, trumpet, saxophone, and a voice combine to express deep meaning about life. Number of Words: 1,357 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Nonfi ction Text Structure • Third-person voice in a continuous narrative • Several topics, including the development and evolution of the blues • Underlying structures include description, sequence, and compare/contrast Content • History of blues music in the United States • Infl uence of blues music on other styles of music Themes and Ideas • Themes of racism, social class barriers, and weaving of blues into popular culture • The blues offers a timeless, enjoyable diversion for many people. • The blues has a rich and varied history that can be traced to Africa. Language and • Descriptive language, including fi gurative language Literary Features • Some inference required to comprehend trends in blues over time Sentence Complexity • Some complex sentences contain embedded, dependent clauses • Lyrics included to show patterns in blues lyrics Vocabulary • Technical words and concepts about music: lyrics, verses, solo, rhythm, records Words • Some words which may be unfamiliar: saxophone, plantations, audiences • Some multisyllable words: genuinely, innovation, parallel, predominantly, tendency Illustrations • Full range of graphics, some dense and challenging Book and Print Features • Fourteen pages of text, with graphics or photographs on most pages • Table of contents, headings, captions, timeline, and map © 2006. Fountas, I.C. & Pinnell, G.S. Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company All rights reserved.