" African Blues": the Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

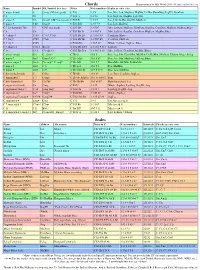

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

The Blues Blue

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 56 A grammatical Conundrum the blues Using “blue” and “the blues” Glossary to denote sadness is not recent BACKBEAT—a rhythmic emphasis on the second and fourth beats of a measure. English slang. The word blue BAR—a musical measure, which is a repeated rhythmic pattern of several beats, usually four quarter notes (4/4) for the blues. The blues usually has twelve bars per was associated with sadness verse. and melancholia in Eliza- BLUE NOTE—the slight lowering downward, usually of the third or seventh notes, of a major scale. Some blues musicians, especially singers, guitarists and bethan England. The Ameri- harmonica players, bend notes upward to reach the blue note. can writer Washington Irving CHOPS—the various patterns that a musician plays, including basic scales. When blues musicians get together for jam sessions, players of the same instrument used the term the blues in sometimes engage in musical duels in front of a rhythm section to see who has the “hottest chops” (plays best). 1807. Grammatically speak- CHORD—a combination of notes played at the same time. ing, however, the term the CHORD PROGRESSION—the use of a series of chords over a song verse that is repeated for each verse. blues is a conundrum: should FIELD HOLLERS—songs that African-Americans sang as they worked, first as it be treated grammatically slaves, then as freed laborers, in which the workers would sing a phrase in response to a line sung by the song leader. as a singular or plural noun? GOSPEL MUSIC—a style of religious music heard in some black churches that The Merriam-Webster una- contains call-and-response arrangements similar to field hollers. -

Blues Poetry As a Celebration of African American Folk Art

ABSTRACT RUTTER, EMILY R. Blues-Inspired Poetry: Jean Toomer, Sterling Brown and the BLKARTSOUTH Collective. (Under the direction of Professor Thomas Lisk). Adopting the blues to lyric poetry marks an implicit rejection of the conventions of the Anglo-American literary establishment, and asserts that African American folk traditions are an equally valuable source of poetic inspiration. During the Harlem Renaissance, Jean Toomer’s Cane (1923) exemplified the incorporation of African American folk forms such as the blues with conventional English poetics. His contemporary Sterling Brown similarly created hybrid forms in Southern Road (1932) that combined African American oral and aural traditions with Anglo-American ones. These texts suggest that blues music represents a complex and sophisticated lyrical form, and its thematic tropes poignantly express the history and contemporary realities of black Americans. In the late 1960s, members of New Orleans’s BLKARTSOUTH were influenced by African American musical traditions as a reflection of historical experience and lyrical expression, and their poetry emphasizes the importance of the blues. Led by Kalamu Ya Salaam and Tom Dent, these poets were part of the Black Arts Movement whose political objectives emphasized a separation from the conventions of the Anglo-American literary establishment, and their work suggests a rejection of traditional English poetics. Although they did not openly acknowledge their literary debt to Toomer and Brown, Cane and Southern Road laid the lyrical foundation for the blues-inspired poetry of Salaam, Dent and their colleagues. What unites these generations of poets is their adoption of the blues theme of resilience in response to the social, political and cultural issues of their eras. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Blues Notes June 2016

VOLUME TWENTY-ONE, NUMBER SIX • JUNE 2016 Sunday, June 5th @ 5 pm - Zoo Bar CURTIS SALGADO Tuesday, June 7th @ 6 pm • 21st Saloon, Omaha, NE $10 for BSO members, $20 for non-members Join the BSO or renew at the door Advance tix @ www.eventbrite.com GOLDEN STATE - LONE STAR REVUE Also Appearing Thursday, June 30th @ 5 pm $15 Wednesday, June 8th @ 6 pm • Zoo Bar, Lincoln, NE 21st Saloon, Omaha WEEKLY BLUES SERIES 4727 S 96th Plaza SOARING WINGS BLUES FESTIVAL Thurs. shows @ 6pm • Sat. shows @ 8 pm with John Primer & Watermelon Slim Bands subject to change Saturday, June 4th June 2nd .............................................................Davy Knowles ($10) June 4th (8 pm) ... Swamp Productions Presents Swampboy Blues Band, SUMMER ARTS FESTIVAL Sweet Tea, Bad Judgement & 40 Sinners ($5) June 10, 11, & 12 June 7th (Tues)........................................................... Curtis Salgado Featuring ($10 BSO Members, $20 Non Members, Bernard Allison Friday, June10th advance tickets at www.eventbrite.com) June 9th (5 pm) ......................................... Tale of 3 Cities Tour ($10) BLUES AT BEL AIR Hector Anchondo, Amanda Fish, and Delta Sol - Sunday June 12th Front and Center opens at 5pm! featuring June 10th (9 pm) ........Achilles Last Stand - Led Zepplin Tribute ($5) The Mighty Jailbreakers June 11th (8 pm) .... Luther James Band ($5) Summer Arts Fest After Party and The Bel Airs June 16th (5 pm) .......... Markey Blue ($10) - Dilemma opens at 5pm June 18th (8 pm) ........ Blue House and the Rent to Own Horns ($5) BRIDGE BEATS June 23rd (5 pm) ....Bruce Katz Band ($10) - Far & Wide opens at 5pm Saturday June 10th & 24th June 25th (8 pm) ............................................Rhythm Collective ($5) June 30th (5 pm) ................... -

From African to African American: the Creolization of African Culture

From African to African American: The Creolization of African Culture Melvin A. Obey Community Services So long So far away Is Africa Not even memories alive Save those that songs Beat back into the blood... Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue So long So far away Is Africa -Langston Hughes, Free in a White Society INTRODUCTION When I started working in HISD’s Community Services my first assignment was working with inner city students that came to us straight from TYC (Texas Youth Commission). Many of these young secondary students had committed serious crimes, but at that time they were not treated as adults in the courts. Teaching these young students was a rewarding and enriching experience. You really had to be up close and personal with these students when dealing with emotional problems that would arise each day. Problems of anguish, sadness, low self-esteem, disappointment, loneliness, and of not being wanted or loved, were always present. The teacher had to administer to all of these needs, and in so doing got to know and understand the students. Each personality had to be addressed individually. Many of these students came from one parent homes, where the parent had to work and the student went unsupervised most of the time. In many instances, students were the victims of circumstances beyond their control, the problems of their homes and communities spilled over into academics. The teachers have to do all they can to advise and console, without getting involved to the extent that they lose their effectiveness. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

Prophet Singer: the Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie

Prophet Singer Prophet Singer THE VOICE AND VISION OF WOODY GUTHRIE MARK ALLAN JACKSON UNIVERSITY PRESS OF MISSISSIPPI / JACKSON AMERICAN MADE MUSIC SERIES ADVISORY BOARD DAVID EVANS, GENERAL EDITOR JOHN EDWARD HASSE BARRY JEAN ANCELET KIP LORNELL EDWARD A. BERLIN FRANK MC ARTHUR JOYCE J. BOLDEN BILL MALONE ROB BOWMAN EDDIE S. MEADOWS SUSAN C. COOK MANUEL H. PEÑA CURTIS ELLISON DAVID SANJEK WILLIAM FERRIS WAYNE D. SHIRLEY MICHAEL HARRIS ROBERT WALSER www.upress.state.ms.us The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses. Frontis: An illustration of the vigilante actions of various “Citizens Committees,” c. 1946. Sketch by Woody Guthrie. Courtesy of the Ralph Rinzler Archives. Copyright © 2007 by University Press of Mississippi All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition 2007 ϱ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jackson, Mark Allan. Prophet singer : the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie / Mark Allan Jackson. — 1st ed. p. cm. — (American made music series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-57806-915-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-57806-915-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Guthrie, Woody, 1912–1967. 2. Folk singers—United States—Biography. 3. Folk music—Social aspects—United States. I. Title. ML410.G978J33 2007 782.42162Ј130092—dc22 [B] 2006020846 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS [ vii ] PROLOGUE [ 3 ] GIVING A VOICE TO LIVING SONGS CHAPTER ONE [ 19 ] Is This Song Your