Singing the Blues...Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

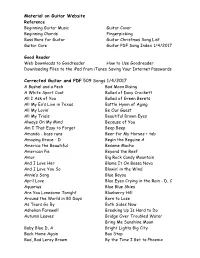

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

TOP SONGWRITER CHART Sunday, July 7, 2019

Sunday, October 14, 2018 TOP SONGWRITER CHART Sunday, July 7, 2019 This Last Songwriter’s Name Song(s) Artist Week Week 1 2 Ashley Gorley Catch Brett Young Good Vibes Chris Janson I Don’t Know About You Chris Lane Living Dierks Bentley One Big Country Song LOCASH Ridin’ Roads Dustin Lynch Rumor Lee Brice 2 1 Michael Hardy God’s Country Blake Shelton I Don’t Know About You Chris Lane One Big Country Song LOCASH Rednecker HARDY Talk You Out Of It Florida Georgia Line 3 4 Hillary Lindsey Buy My Own Drinks Runaway June Closer To You Carly Pearce Knockin’ Boots Luke Bryan 4 5 Bobby Pinson Homemade Jake Owen Rearview Town Jason Aldean Some Of It Eric Church 5 6 Ben Burgess Whiskey Glasses Morgan Wallen 6 7 Kevin Kadish Whiskey Glasses Morgan Wallen 7 8 Jordan M. Schmidt God’s Country Blake Shelton Rednecker HARDY 8 9 Blanco Brown The Git Up Blanco Brown 9 14 Jon Nite I Hope Gabby Barrett Knockin’ Boots Luke Bryan Living Dierks Bentley 10 10 Jeffery Hyde Some Of It Eric Church We Were Keith Urban 11 11 Eric Church Some Of It Eric Church We Were Keith Urban 12 3 Luke Combs Beer Never Broke My Heart Luke Combs Even Though I’m Leaving Luke Combs Lovin’ On You Luke Combs Moon Over Mexico Luke Combs Refrigerator Door Luke Combs 13 12 Gordie Sampson Closer To You Carly Pearce Family Tree Caylee Hammack Knockin’ Boots Luke Bryan 14 13 Cary Barlowe Back To Life Rascal Flatts Raised On Country Chris Young 15 15 Maren Morris Girl Maren Morris The Bones Maren Morris 16 19 Jameson Rodgers I Don’t Know About You Chris Lane Talk You Out Of It Florida Georgia -

Issue 469 Motor Mouths: Country in Detroit “Detroit: Cars and Rock ‘N’ Roll

October 12, 2015, Issue 469 Motor Mouths: Country In Detroit “Detroit: Cars and Rock ‘n’ Roll. Not a bad combo.” Nice, Kid Rock. But what are either without radio? Motor City call letters including WCSX, WRIF, WOMC, WKQI, WJR, WWWW and WYCD have become famous over the years with help from Rock and Roll Hall of Famers Steve Kostan and Arthur Penhallow, National Radio Hall of Famers Dick Purtan, J.P. McCarthy, Steve Dahl and Howard Stern, and Country Radio Hall of Famer Dr. Don Carpenter, to name a few. Not a bad pedigree. PPM market No. 12 is changing, though, especially with respect to Country. For starters, CBS Radio’s WYCD got its first direct challenger in four years when Cumulus Adult Hits WDRQ adopted the company’s Nash brand in late 2013 (Breaking News 12/13/13). And just a few weeks ago Carpenter ended his 10- year WYCD morning run, which led to other on-air changes at the station (CAT 8/5). Country Aircheck details some of those and checks WDRQ’s progress here. Write On: Rosanne Cash, Mark James, Even Stevens On The Market: Detroit – Rust Belt city or city on a and Craig Wiseman were inducted into the Nashville comeback? “Detroit is on a great comeback, but there was a time Songwriters Hall Fame last night (10/11) at the 45th Anniversary Hall of Fame Gala held at the Music City where people moved out of the market,” says Center. Pictured l-r: NaSHOF Board Chair Pat Alger, James, WYCD OM/PD Tim Roberts. -

Brad Paisley Wheelhouse Mp3, Flac, Wma

Brad Paisley Wheelhouse mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Wheelhouse Country: US Released: 2013 Style: Country MP3 version RAR size: 1580 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1204 mb WMA version RAR size: 1468 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 958 Other Formats: DXD DMF AHX MP4 APE FLAC AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Bon Voyage 0:18 2 Southern Comfort Zone 5:17 3 Beat This Summer 4:41 Outstanding In Our Field 4 Featuring – Dierks Bentley, Roger MillerFeaturing [With], Guitar – Hunter 4:02 Hayes Pressing On A Bruise 5 3:17 Featuring – Mat Kearney 6 I Can't Change The World 4:41 7 幽女 1:39 Karate 8 4:05 Featuring – Charlie Daniels Death Of A Married Man 9 0:48 Featuring – Eric Idle 10 Harvey Bodine 3:29 11 Tin Can On A String 4:09 12 Death Of A Single Man 4:25 13 The Mona Lisa 3:54 Accidental Racist 14 5:51 Featuring – LL Cool J 15 Runaway Train 4:28 16 Those Crazy Christians 4:21 17 Officially Alive 3:55 Bonus Tracks: 18 Only Way She'll Stay 3:16 19 She Never Really Got Over Him 3:05 20 Beat This Summer (Acoustic) 3:36 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Sony Music Entertainment Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment Pressed By – Sony DADC – DIDX-836124 Recorded At – The Wheelhouse, Nashville Mastered At – Gateway Mastering & DVD Exclusive Retailer – Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Credits Backing Vocals – Carl Jackson (tracks: 4, 15), Sheryl Crow (tracks: 8) Backing Vocals [Choral Backgrounds] – Chris Stapleton (tracks: 14) Bass [Additional On Bridge] – Luke Wooten -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PETER KOVACH Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: April 18, 2012 Copyright 2015 ADST Q: Today is the 18th of April, 2012. Do you know ‘Twas the 18th of April in ‘75’? KOVACH: Hardly a man is now alive that remembers that famous day and year. I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts. Q: We are talking about the ride of Paul Revere. KOVACH: I am a son of Massachusetts but the first born child of either side of my family born in the United States; and a son of Massachusetts. Q: Today again is 18 April, 2012. This is an interview with Peter Kovach. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by Peter? KOVACH: Peter is fine. Q: Let s start at the beginning. When and where were you born? KOVACH: I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts three days after World War II ended, August the 18th, 1945. Q: Let s talk about on your father s side first. What do you know about the Kovaches? KOVACH: The Kovaches are a typically mixed Hapsburg family; some from Slovakia, some from Hungary, some from Austria, some from Northern Germany and probably some from what is now western Romania. Predominantly Jewish in background though not practice with some Catholic intermarriage and Muslim conversion. Q: Let s take grandfather on the Kovach side. Where did he come from? KOVACH: He was born I think in 1873 or so. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

14Th Annual ACM Honors Celebrates Industry & Studio Recording Winners from 55Th & 56Th ACM Awards

August 27, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, August 27, 2021 14th Annual ACM Honors Celebrates SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) Industry & Studio Recording Winners From 55th & 56th ACM Awards If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES 14th Annual ACM Honors Beloved TV Journalist And Producer Lisa Lee Dies At 52 “The Storyteller“ Tom T. Hall Passes Luke Combs accepts the Gene Weed Milestone Award while Ashley McBryde Rock And Country Titan Don looks on. Photo: Getty Images / Courtesy of the Academy of Country Music Everly Passes Kelly Rich To Exit Amazon The Academy of Country Music presented the 14th Annual ACM Honors, Music recognizing the special award honorees, and Industry and Studio Recording Award winners from the 55th and 56th Academy of Country SMACKSongs Promotes Music Awards. Four The event featured a star-studded lineup of live performances and award presentations celebrating Special Awards recipients Joe Galante and Kacey Musgraves Announces Rascal Flatts (ACM Cliffie Stone Icon Award), Lady A and Ross Fourth Studio Album Copperman (ACM Gary Haber Lifting Lives Award), Luke Combs and Michael Strickland (ACM Gene Weed Milestone Award), Dan + Shay Reservoir Inks Deal With (ACM Jim Reeves International Award), RAC Clark (ACM Mae Boren Alabama Axton Service Award), Toby Keith (ACM Merle Haggard Spirit Award), Loretta Lynn, Gretchen Peters and Curly Putman (ACM Poet’s Award) Old Dominion, Lady A and Ken Burns’ Country Music (ACM Tex Ritter Film Award). Announce New Albums Also honored were winners of the 55th ACM Industry Awards, 55th & 56th Alex Kline Signs With Dann ACM Studio Recording Awards, along with 55th and 56th ACM Songwriter Huff, Sheltered Music of the Year winner, Hillary Lindsey. -

Sept. 24, 2009 • Inside • Board Nixes Plans for New Town Hall FORUM

Volume 7, Number 38 PDF Version – www.HighlandsInfo.com Thursday, Sept. 24, 2009 • Inside • Board nixes plans for new Town Hall FORUM ....................... 2 Letters .......................... 2 The biggest news to come out remodeled with funds already on where policies aren’t allowed to be Obituaries ..................... 3 of the Town Board’s worksession hand. set or voted on, Town Attorney Bill Wooldridge ................... 4 Wednesday was the nixing of the Town Manager Jim Fatland Coward said since the worksession Salzarulo ...................... 5 This Week in Highlands plan to build a new Town Hall. said given the current economic was advertised as a Special Meeting From Turtle Pond .......... 6 Thurs.-Sun., Sept. 24-27 During the renovations of the situation and given the fact that cost and Worksession, the Town Hall Coach’s Corner ............. 7 • Highlands Playhouse Antique Show at current Town Hall – meant only to estimates to build a new Town Hall issue could be decided and voted His & Hers .................... 14 the Civic Center. Preview Party Thursday from be used until plans were finalized complex were in excess of $5.4 mil- on if the board so desired. Conservative POV ......... 17 6:30-8:30 p.m., 10-5 Friday and Saturday, noon for a new Town Hall — architects lion, it would be fiscally sound to Though the idea of voting on Events ........................... 26 to 5 on Sunday. $12. Call: 526-2695 for tickets. discovered that the building is cancel plans to build new and ren- something the public didn’t have a Classifieds ..................... 32 Fri.-Sun., Sept. 25-27 sound and could be renovated for a ovate and remodel instead. -

The Beginner's Guide to Nation-Building

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Praise for The Beginner’s Guide to Nation-Building No challenge in international relations today is more pressing or more difficult than that of supporting weak states. James Dob- bins, one of the leading practitioners of the art, offers a set of clear, simple prescriptions for helping to build a stable peace in the wake of conflict and disorder. -

List of Additional Human Rights Songs

THE POWER OF OUR VOICES LIST OF ADDITIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS SONGS This is a list of additional songs linked to human rights issues for teachers who want to expand the topics covered in the lessons. Joan Baez and Mimi Farina The Clash Bread and roses (1976) Know your rights (1982) Women’s liberation song, inspired by the ‘Know your rights all 3 of them… women textile workers’ strike in Massachusetts Number three: You have the right to free in 1912. Speech as long as you’re not Dumb enough to actually try it. Band Aid Know your rights Do they know it’s Christmas? (1984) These are your rights’ Song to raise money for the 1983-1985 famine in Ethiopia. Sam Cooke A change is gonna come (1964) Ludwig van Beethoven On discrimination and racism in 1960s USA. O Welche Lust (1775) The prisoner’s chorus from his opera about a Dire Straits prisoner of conscience jailed for his ideas. Brothers in arms (1985) Anti-war song. Billy Bragg Between the wars (1984) Bob Dylan Song about class division. Only a pawn in their game (1963) Which side are you on? (1984) Song about the racist murder of Medgar Evans, A version of a traditional union song. civil rights campaigner in Mississippi. Joe Hill (1990) Hurricane (1966) Song about a murdered union organiser. Song about Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter, a boxer who spent 19 years in jail for a murder Dylan felt Big Bill Broonzy he did not commit. Black, brown and white blues (1939) Masters of war (1966) Song about racial discrimination in the jobs Song against war and the power of the military- market. -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.