Table of Contents 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

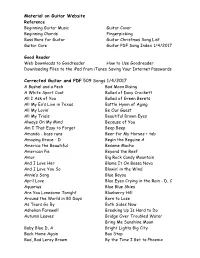

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Memphis, Tennessee, Is Known As the Home of The

Memphis, Tennessee, is known as the Home of the Blues for a reason: Hundreds of bluesmen honed their craft in the city, playing music in Handy Park and in the alleyways that branch off Beale Street, plying their trade in that street’s raucous nightclubs and in juke joints across the Mississippi River. Mississippians like Ike Turner, B.B. King, and Howlin’ Wolf all passed through the Bluff City, often pausing to cut a record before migrating northward to a better life. Other musicians stayed in Memphis, bristling at the idea of starting over in unfamiliar cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Los Angeles. Drummer Finas Newborn was one of the latter – as a bandleader and the father of pianist Phineas and guitarist Calvin Newborn, and as the proprietor of his own musical instrument store on Beale Street, he preferred the familiar environs of Memphis. Finas’ sons literally grew up with musical instruments in their hands. While they were still attending elementary school, the two took first prize at the Palace Theater’s “Amateur Night” show, where Calvin brought down the house singing “Your Mama’s On the Bottom, Papa’s On Top, Sister’s In the Kitchen Hollerin’ ‘When They Gon’ Stop.’” Before Calvin followed his brother Phineas to New York to pursue a jazz career, he interacted with all the major players on Memphis’ blues scene. In fact, B.B. King helped Calvin pick out his first guitar. The favor was repaid when the entire Newborn family backed King on his first recording, “Three O’ Clock Blues,” recorded for the Bullet label at Sam Phillips’ Recording Service in downtown Memphis. -

Johnny Cash by Dave Hoekstra Sept

Johnny Cash by Dave Hoekstra Sept. 11, 1988 HENDERSONVILLE, Tenn. A slow drive from the new steel-and-glass Nashville airport to the old stone-and-timber House of Cash in Hendersonville absorbs a lot of passionate land. A couple of folks have pulled over to inspect a black honky-tonk piano that has been dumped along the roadway. Cabbie Harold Pylant tells me I am the same age Jesus Christ was when he was crucified. Of course, this is before Pylant hands over a liter bottle of ice water that has been blessed by St. Peter. This is life close to the earth. Johnny Cash has spent most of his 56 years near the earth, spiritually and physically. He was born in a three-room railroad shack in Kingsland, Ark. Father Ray Cash was an indigent farmer who, when unable to live off the black dirt, worked on the railroad, picked cotton, chopped wood and became a hobo laborer. Under a New Deal program, the Cash family moved to a more fertile northeastern Arkansas in 1935, where Johnny began work as a child laborer on his dad's 20-acre cotton farm. By the time he was 14, Johnny Cash was making $2.50 a day as a water boy for work gangs along the Tyronza River. "The hard work on the farm is not anything I've ever missed," Cash admitted in a country conversation at his House of Cash offices here, with Tom T. Hall on the turntable and an autographed picture of Emmylou Harris on the wall. -

BBB-2017E.Pdf

Big Blues Bender Official Program 2017 1 Welcome to the Bender! It’s our honor and privilege to welcome you all to the 4th installment of the Big Blues Bender! To our veterans, we hope you can see the attention we have given to the feedback from our community to make this event even better, year after year. To the virgins, welcome to the family - you’re one of us now! You’ll be hard pressed to find a more fun-loving, friendly, and all around excellent group of people than are surrounding you this week. Make new friends of your fellow guests, and be sure to come say hi to all of us. We are here to make your experience the best it can be, and we’re excited to prove it! Finally, we would like to acknowledge the hard work and support of the Plaza Hotel staff and CEO Jonathan Jossel. We could not ask for a better team to make the Bender feel at home. -Much Love, Team Bender BENDER SUPPORT PRE & POST HOURS : Wed, 9/6: 12:00p-11:00p • Mon, 9/11: 10:00a-12:00p PANELS & PARTIES Appear in yellow on the schedule Bender Party With H.A.R.T • Wed, Sept. 6 • 8:00p • Showroom $30 GA - The Official Bender Pre-party is proud to support H.A.R.T. 100% of proceeds benefit the Handy Artists Relief Trust. Veterans Welcome the Virgins Party! • Thu, Sept. 7 • 4:00p • Pool Join Bender veteran and host, Marice Maples, in welcoming this year’s crop of Bender Virgins! The F.A.C.E Of Women In Blues Panel • Fri, Sept. -

Sweet & Lowdown Repertoire

SWEET & LOWDOWN REPERTOIRE COUNTRY 87 Southbound – Wayne Hancock Johnny Yuma – Johnny Cash Always Late with Your Kisses – Lefty Jolene – Dolly Parton Frizzell Keep on Truckin’ Big River – Johnny Cash Lonesome Town – Ricky Nelson Blistered – Johnny Cash Long Black Veil Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain – E Willie Lost Highway – Hank Williams Nelson Lover's Rock – Johnny Horton Bright Lights and Blonde... – Ray Price Lovesick Blues – Hank Williams Bring It on Down – Bob Wills Mama Tried – Merle Haggard Cannonball Blues – Carter Family Memphis Yodel – Jimmy Rodgers Cannonball Rag – Muleskinner Blues – Jimmie Rodgers Cocaine Blues – Johnny Cash My Bucket's Got a Hole in It – Hank Cowboys Sweetheart – Patsy Montana Williams Crazy – Patsy Cline Nine Pound Hammer – Merle Travis Dark as a Dungeon – Merle Travis One Woman Man – Johnny Horton Delhia – Johnny Cash Orange Blossom Special – Johnny Cash Doin’ My Time – Flatt And Scruggs Pistol Packin Mama – Al Dexter Don't Ever Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Please Don't Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Don't Take Your Guns to Town – Johnny Poncho Pony – Patsy Montana Cash Ramblin' Man – Hank Williams Folsom Prison Blues – Johnny Cash Ring of Fire – Johnny Cash Ghost Riders in the Sky – Johnny Cash Sadie Brown – Jimmie Rodgers Hello Darlin – Conway Twitty Setting the Woods on Fire – Hank Williams Hey Good Lookin’ – Hank Williams Sitting on Top of the World Home of the Blues – Johnny Cash Sixteen Tons – Merle Travis Honky Tonk Man – Johnny Horton Steel Guitar Rag Honky Tonkin' – Hank Williams Sunday Morning Coming -

CONSTRUCTING TIN PAN ALLEY 17 M01 GARO3788 05 SE C01.Qxd 5/26/10 4:35 PM Page 18

M01_GARO3788_05_SE_C01.qxd 5/26/10 4:35 PM Page 15 Constructing Tin Pan 1 Alley: From Minstrelsy to Mass Culture The institution of slavery has been such a defining feature of U.S. history that it is hardly surprising to find the roots of our popular music embedded in this tortured legacy. Indeed, the first indige- nous U.S. popular music to capture the imagination of a broad public, at home and abroad, was blackface minstrelsy, a cultural form involving mostly Northern whites in blackened faces, parodying their perceptions of African American culture. Minstrelsy appeared at a time when songwriting and music publishing were dispersed throughout the country and sound record- The institution of slavery has been ing had not yet been invented. During this period, there was an such a defining feature of U.S. history that it is hardly surprising to find the important geographical pattern in the way music circulated. Concert roots of our popular music embedded music by foreign composers intended for elite U.S. audiences gener- in this tortured legacy. ally played in New York City first and then in other major cities. In contrast, domestic popular music, including minstrel music, was first tested in smaller towns, then went to larger urban areas, and entered New York only after success elsewhere. Songwriting and music publishing were similarly dispersed. New York did not become the nerve center for indigenous popular music until later in the nineteenth century, when the pre- viously scattered conglomeration of songwriters and publishers began to converge on the Broadway and 28th Street section of the city, in an area that came to be called Tin Pan Alley after the tinny output of its upright pianos. -

2009–Senior Seminar, Ives, Blues, Porter

James Hepokoski Spring 2009 Music 458: Ives, Blues, Porter Visions of America: Competing concepts of musical style and purpose in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century. We examine some stylistic and cultural bases of both “art” and “popular” music and their often uneasy interrelationships. This is neither a survey course nor one concerned with mastering a body of facts. Nor is it preoccupied with coming to aesthetic value judgments. Instead, it is a course in applying critical thinking and analysis to some familiar musical styles basic to the American experience: asking hard questions of differing early- and mid-twentieth-century repertories. Areas to be examined include: 1) Ives (selected songs, Concord Sonata, Second Symphony); 2) early blues (Bessie Smith, Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, and others), including samples of African-American recorded precedents and related genres; 3) Broadway and popular song—including a brief look at Jerome Kern (selected numbers from Show Boat) followed by a closer study of Cole Porter (Anything Goes). Some main questions to be faced are: What aesthetic/contextual/analytical tools do we need to think more deeply about differing pieces of music that spring from or respond to markedly differing/diverse American subcultures? What are our presuppositions in listening to any of these musics, and to what extent might we profit by examining these presuppositions critically? The course will also make use of resources in Yale’s music collection—most notably the Charles Ives Papers and The Cole Porter Collection. We shall also be concerned with original recordings from the 1920s and 1930s. -

Understanding Music Popular Music in the United States

Popular Music in the United States 8 N. Alan Clark and Thomas Heflin 8.1 OBJECTIVES • Basic knowledge of the history and origins of popular styles • Basic knowledge of representative artists in various popular styles • Ability to recognize representative music from various popular styles • Ability to identify the development of Ragtime, the Blues, Early Jazz, Bebop, Fusion, Rock, and other popular styles as a synthesis of both African and Western European musical practices • Ability to recognize important style traits of Early Jazz, the Blues, Big Band Jazz, Bebop, Cool Jazz, Fusion, Rock, and Country • Ability to identify important historical facts about Early Jazz, the Blues, Big Band Jazz, Bebop, Cool Jazz, Fusion, and Rock music • Ability to recognize important composers of Early Jazz, the Blues, Big Band Jazz, Bebop, Cool Jazz, Fusion, and Rock music 8.2 KEY TERMS • 45’s • Bob Dylan • A Tribe Called Quest • Broadway Musical • Alan Freed • Charles “Buddy” Bolden • Arthur Pryor • Chestnut Valley • Ballads • Children’s Song • BB King • Chuck Berry • Bebop • Contemporary Country • Big Band • Contemporary R&B • Bluegrass • Count Basie • Blues • Country Page | 255 UNDERSTANDING MUSIC POPULAR MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES • Creole • Protest Song • Curtis Blow • Ragtime • Dance Music • Rap • Dixieland • Ray Charles • Duane Eddy • Rhythm and Blues • Duke Ellington • Richard Rodgers • Earth, Wind & Fire • Ricky Skaggs • Elvis Presley • Robert Johnson • Folk Music • Rock and Roll • Frank Sinatra • Sampling • Fusion • Scott Joplin • George Gershwin • Scratching • Hillbilly Music • Stan Kenton • Honky Tonk Music • Stan Kenton • Improvisation • Stephen Foster • Jelly Roll Morton • Storyville • Joan Baez • Swing • Leonard Bernstein • Syncopated • Louis Armstrong • The Beatles • LPs • Victor Herbert • Michael Bublé • Weather Report • Minstrel Show • Western Swing • Musical Theatre • William Billings • Operetta • WJW Radio • Original Dixieland Jazz Band • Work Songs • Oscar Hammerstein 8.3 INTRODUCTION Popular music is by definition music that is disseminated widely. -

" African Blues": the Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse

“African Blues”: The Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse A thesis submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Saul Meyerson-Knox BA, Guilford College, 2007 Committee Chair: Stefan Fiol, PhD Abstract This thesis explores the musical style known as “African Blues” in terms of its historical and social implications. Contemporary West African music sold as “African Blues” has become commercially successful in the West in part because of popular notions of the connection between American blues and African music. Significant scholarship has attempted to cite the “home of the blues” in Africa and prove the retention of African music traits in the blues; however much of this is based on problematic assumptions and preconceived notions of “the blues.” Since the earliest studies, “the blues” has been grounded in discourse of racial difference, authenticity, and origin-seeking, which have characterized the blues narrative and the conceptualization of the music. This study shows how the bi-directional movement of music has been used by scholars, record companies, and performing artist for different reasons without full consideration of its historical implications. i Copyright © 2013 by Saul Meyerson-Knox All rights reserved. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Stefan Fiol for his support, inspiration, and enthusiasm. Dr. Fiol introduced me to the field of ethnomusicology, and his courses and performance labs have changed the way I think about music. -

Disk Catalog by Category

COUNTRY: 50's 60's - KaraokeStar.com 800-386-5743 or 602-569-7827 COUNTRY: 50's & 60's COUNTRY: 50's & 60's COUNTRY: 50's & 60's COUNTRY: 50's & 60's You Are My Sunshine Autry, Gene Then And Only Then Smith, Connie Vocal Guides: Yes Vocal Guides: No CB20499 Lyric Sheet: No Wagon Wheels Arnold, Eddy CB60294 Lyric Sheet: No I'll Hold You In My Heart Arnold, Eddy Faster Horses Hall, Tom T You Two Timed Me One Time T Ritter, Tex Chartbuster 6+6 Country KaraokeStar.com Chartbuster Pro Country KaraokeStar.com Snakes Crawl At Night, The Pride, Charley Am I That Easy To Forget David, Skeeter Hits Of Eddy Arnold Vol 1 $12.99 Chartbuster Country Vol 294 $19.99 Big Boss Man Rich, Charlie Don't Fence Me In Autry, Gene Make The World Go Away Arnold, Eddy My Shoes Keep Walking Back To Price, Ray Don't Cry Joni Twitty, Conway Don't Rob Another Man's Castle Arnold, Eddy You Don't Know Me Arnold, Eddy Filipino Baby Tubb, Ernest You're The Best Thing That Ever Price, Ray Take Me To Your World Wynette, Tammy Anytime Arnold, Eddy Blue Side Of Lonesome Reeves, Jim It's So Easy Ronstadt, Linda Bouquet Of Roses Arnold, Eddy Crystal Chandeliers Pride, Charley Vocal Guides: No Mom And Dad's Waltz Frizzell, Lefty CB60333 Lyric Sheet: No Cattle Call Arnold, Eddy I've Done Enough Dyin' TodayGatlin, Larry & The KaraokeStar.com What's He Doing In My World Arnold, Eddy Vocal Guides: No It's All Wrong But It's All Right Parton, Dolly Chartbuster Classic Country CB60282 Lyric Sheet: No Classic Country Vol 333 Pop A Top Brown, Jim Ed $19.99 KaraokeStar.com Vocal Guides: -

Tributaries on the Name of the Journal: “Alabama’S Waterways Intersect Its Folk- Ways at Every Level

Tributaries On the name of the journal: “Alabama’s waterways intersect its folk- ways at every level. Early settlement and cultural diffusion conformed to drainage patterns. The Coastal Plain, the Black Belt, the Foothills, and the Tennessee Valley re- main distinct traditional as well as economic regions today. The state’s cultural landscape, like its physical one, features a network of “tributaries” rather than a single dominant mainstream.” —Jim Carnes, from the Premiere Issue JournalTributaries of the Alabama Folklife Association Joey Brackner Editor 2002 Copyright 2002 by the Alabama Folklife Association. All Rights Reserved. Issue No. 5 in this Series. ISBN 0-9672672-4-2 Published for the Alabama Folklife Association by NewSouth Books, Montgomery, Alabama, with support from the Folklife Program of the Alabama State Council on the Arts. The Alabama Folklife Association c/o The Alabama Center for Traditional Culture 410 N. Hull Street Montgomery, AL 36104 Kern Jackson Al Thomas President Treasurer Joyce Cauthen Executive Director Contents Editor’s Note ................................................................................... 7 The Life and Death of Pioneer Bluesman Butler “String Beans” May: “Been Here, Made His Quick Duck, And Got Away” .......... Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott 9 Butler County Blues ................................................... Kevin Nutt 49 Tracking Down a Legend: The “Jaybird” Coleman Story ................James Patrick Cather 62 A Life of the Blues .............................................. Willie Earl King 69 Livingston, Alabama, Blues:The Significance of Vera Ward Hall ................................. Jerrilyn McGregory 72 A Blues Photo Essay ................................................. Axel Küstner Insert A Vera Hall Discography ...... Steve Grauberger and Kevin Nutt 82 Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress .................John Garst 92 Recording Review ........................................................ -

1 Fulfillment of Prophecy Singing the Sacred Core 52 – Week 10 We

1 Fulfillment of Prophecy Singing the Sacred Core 52 – Week 10 We have songs for every occasion. Music for every mood. You’ve just been through a bad breakup, you grab your Kleenex and you put Someone Like You by Adele on repeat. You’re singing your child to sleep at bedtime, you swing a sweet lullaby like Rock-a-bye-baby while you secretly wonder what kind of freak puts their baby in a treetop. You’re getting pumped up for the big game , so you’re going to blast Get Ready by 2 Unlimited. You want to rock out, you crank the volume up to 11 and listen to For Those About to Rock. You’re feeling romantic, you dig out the old vinyl, you drop the lights and you drop the needle on When a Man Loves a Woman. You’re about to hit the gym and get your sweat on, you’ll pump some Survivor by Destiny’s Child. In the same way, there are many kings of songs in the book of Psalms. There were songs to be sung to prepare you for worship. There are songs of thanksgiving. There are wisdom psalms. There are even what are called the Psalms of Lament, which is their version of the sad songs. They are what Israel sang when they felt like singing the blues. They had all these different kinds of songs for all these different occasions. One kind of song we find in the Psalms might be unfamiliar to us. They are the royal psalms.